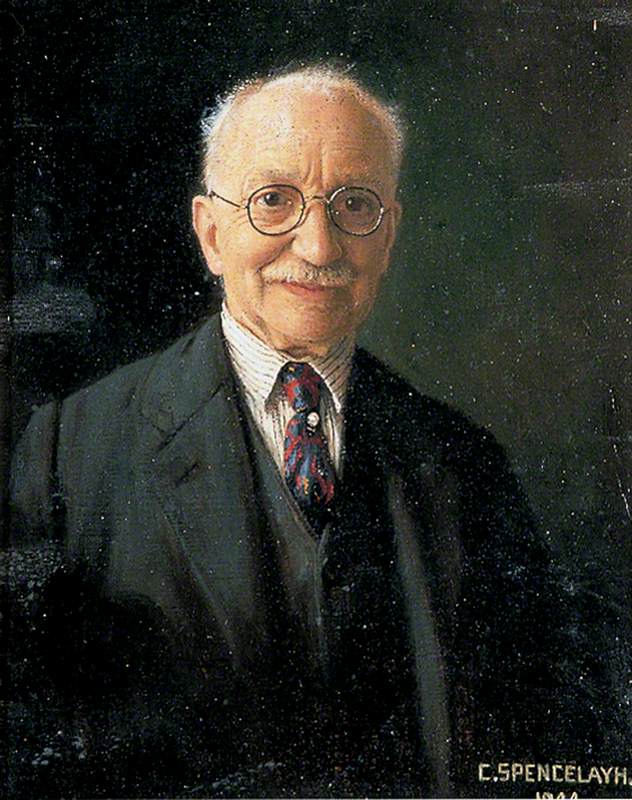

It is at first very surprising that the picture that is most frequently reproduced and lent out to major exhibitions from the University of Hull Art Collection is a small (40 x 50.6 cm) canvas featuring a bust-length side view of a seated, balding man in a dark suit. When painted in 1918 he was probably regarded as a figure in rude good health. Today his doctor might suggest that he count his calories and they would probably enquire about his consumption of units a week.

Image credit: University of Hull Art Collection

He Gained a Fortune but He Gave a Son 1918

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889–1946)

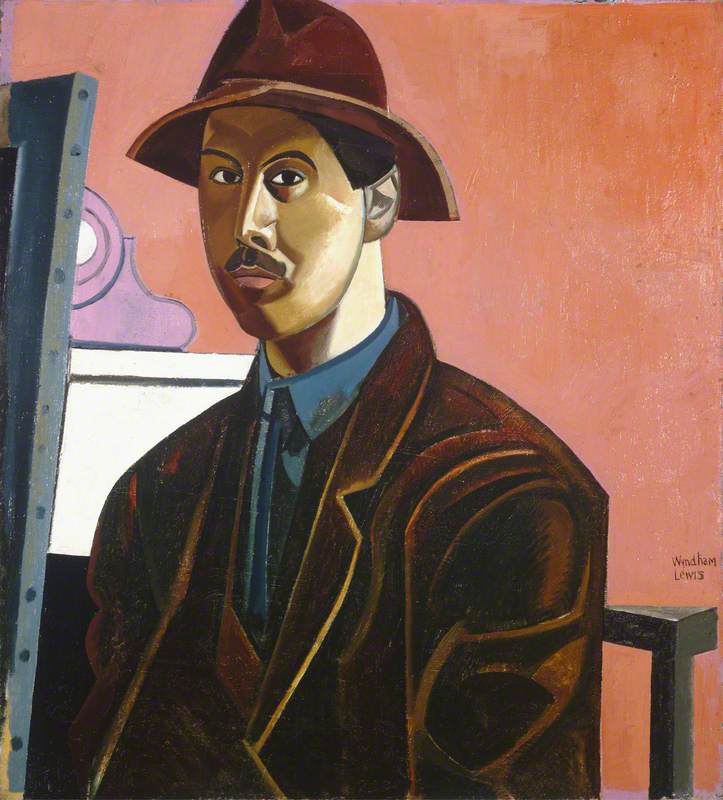

University of Hull Art CollectionThe University of Hull Art Collection specialises in Art in Britain 1890–1940, but in a collection that boasts fine examples by Walter Sickert, Lucien Pissarro, Augustus John, Stanley Spencer, Vanessa Bell, Wyndham Lewis and Ben Nicholson, it seems odd that this one should be so popular. Partly this is down to the artist but mostly it is because of the subject matter and the unusual fact that the painting has two very different subjects. It is both a war painting and an illustration of the world of 'upstairs downstairs', and it appears, as appropriate, in frequent exhibitions and books on those two themes.

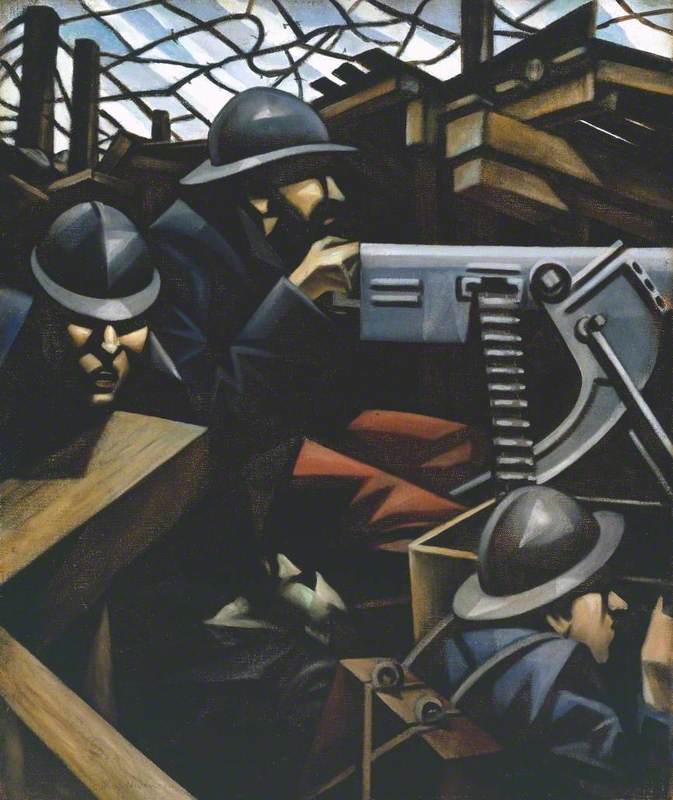

The artist, Christopher Nevinson (1889–1946), was a contemporary of Ben Nicholson, Stanley Spencer and Paul Nash at the Slade School of Fine Art and went on to produce some of the most striking and moving images of the First World War. The Hull picture was painted as a moralising piece, showing a war profiteer who for all his financial gains lost his son in the First World War. A photograph of the son, in uniform, sits on the mantelpiece.

The sitter for the profiteer was Henry Moat who was a butler/valet. He entered service with the celebrated aristocratic and literary Sitwell family as a footman in 1893 and rose to the position of butler. This role is alluded to in the picture by the prominent bell push on the wall to the left, as the symbol of his trade. Moat died in February 1940 and did not have a legitimate son, though he was rumoured to have had several illegitimate children. Ironically, he was serving in the Army Service Corps at the time the work was painted, as he did throughout the war. He is mentioned frequently in Sir Osbert Sitwell's autobiography Left Hand Right Hand (volumes 1–4, 1945–1950) as a larger than life character and frequent embodiment of sound sense in contrast to the eccentricities of his master, Sir George Sitwell, in particular. Edith Sitwell described Moat as an 'enormous purple man, like a benevolent hippopotamus with a voice like some foghorn endowed with splendour' [Taken Care Of, 1965, p.28]. Sir George, with whom he had a frequently tempestuous relationship, referred to him as ‘the great man’ and he is one of very few servants who have earned an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [Philip Carter, ‘Moat, Henry’, Oxford DNB, 2006].

The painting was purchased by the University Collection in 1968 under the title Mr Moat but we have since adopted the original title of 1918, He Gained a Fortune but He Gave a Son. It also gained a third identity when the artist’s father, Henry Wood Nevinson, reproduced it under the title Bourgois in a chapter on the middle classes in his book Rough Islanders or the Natives of England in 1930.

A recent critic has described the painting as ‘a portrait of a smug self-satisfied banker’ (Paul Bond, World Socialist Web Site, 5 January 2000) but surely Nevinson presents us with a more sympathetic image, and in the duality of war profiteer and butler there is much of the real Henry Moat that emerges.

John G. Bernasconi, Director of Fine Art, University of Hull