'I have a very great respect for [Angus] Neil's work and I consider Scotland to have lost a great artist due to his illness.' In 1979, Ian Mackenzie Smith, then director of Aberdeen Art Gallery, was not writing Neil's obituary, but appealing for funding to help revive him.

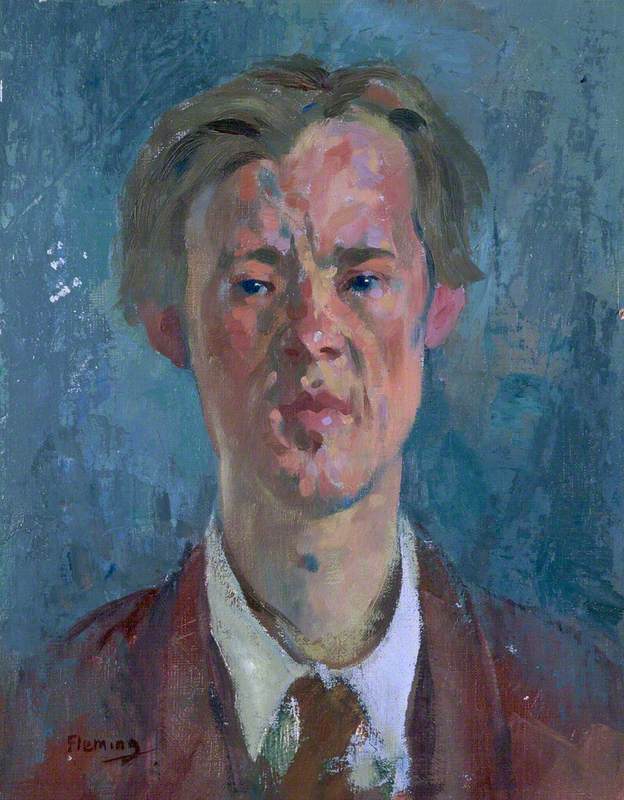

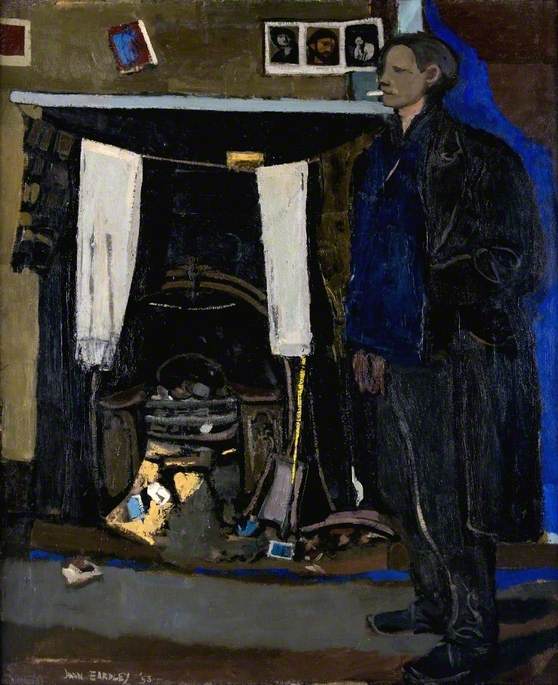

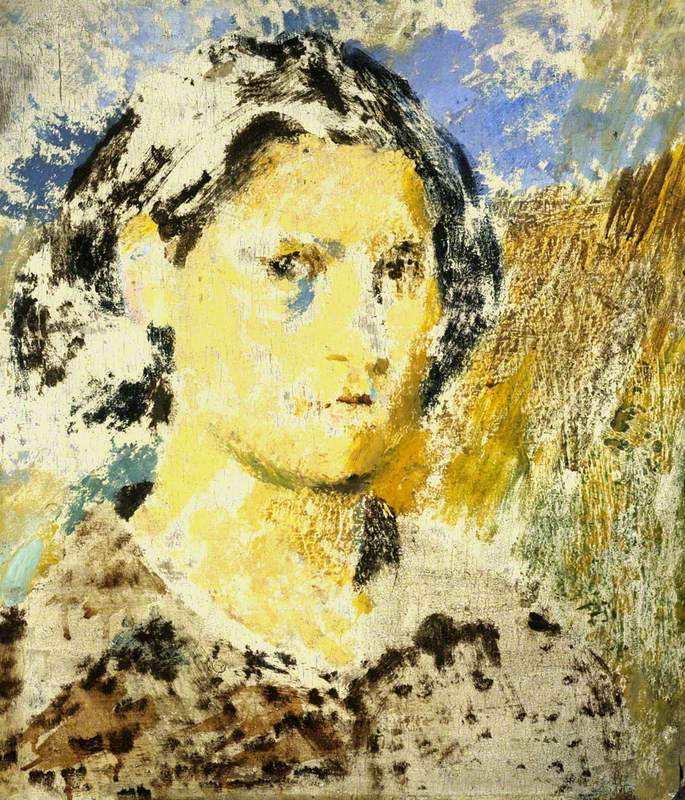

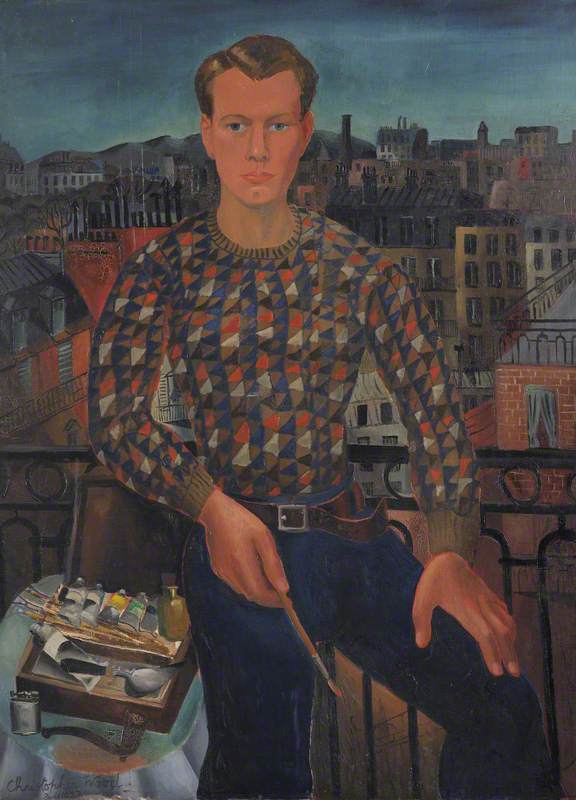

Angus Neil (1924–1992) was an elusive presence in the Scottish art world of the 1950s to 1980s. Initially a student of James Cowie at the Hospitalfield residential school of art in Arbroath, he became a lifelong friend of Joan Eardley. Working by her side, he studied part-time at Glasgow School of Art, then moved to be near her in Catterline, on the Aberdeenshire coast.

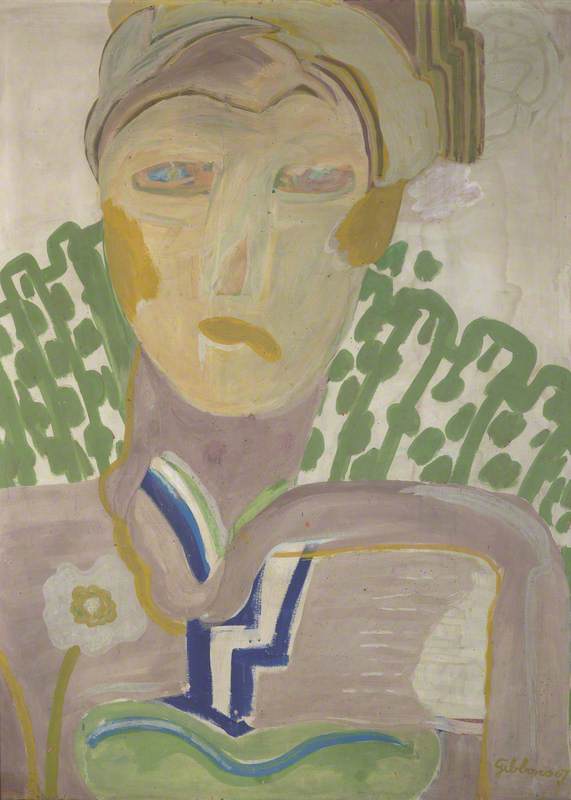

After Eardley's death in 1963, Neil went to artist Carole Gibbons for support, because Eardley had admired her work.

Neil already struggled with his mental health. After a turbulent childhood, in his late teens, he suffered shellshock serving as a wireless operator in the Second World War. But it was his bereavement over Eardley, and the events which followed, that ultimately overwhelmed him. Eventually destitute, it was only his admission to psychiatric care which saved him. He would spend most of the second half of his life in mental health institutions, first at Dundee Liff Hospital, then at Sunnyside Royal Hospital, Montrose.

This was only the beginning of the story (for the purposes of this article, at least). Neil did not simply lose the will to work and fade from the scene. His struggle to work creatively was well documented, stifled by the health care system which was also his lifeline. 'This is not a fairy story' he wrote. 'I set out to be an artist a long time ago. well its turned out to be impossible following the path of destiny is one thing getting certified and locked up is quite another'.

From hospital, he sent copious letters to Aberdeen Art Gallery, many addressed to Mackenzie Smith, then later to curator Francina Irwin. The correspondence began in 1977 when Neil's loyal patron, Thomas Craig, donated The Last Supper (below) to the gallery, and it continued until the artist's death in 1992. The letters are now publicly accessible at Aberdeen Archives, Gallery & Museums' Treasure Hub, alongside other records and donated correspondence.

Delving into Neil's personal communications feels admittedly intrusive, yet his experiences speak strongly from a world normally hidden from view. Of all the people who have been compelled to live in mental health institutions, it is rare to hear their individual voices. It is the emotional content and Neil's frustrations with his environment which are most revealing. His accounts not only enrich our understanding of his work but also highlight the vital importance of the creative process to our mental well-being.

Almost every letter refers back to Joan Eardley in some respect. 'I wasn't just in love with Joan Eardley I was in love with everything about her'. Eardley was gay but consistently devoted, encouraging him professionally and providing essential reassurance and stability. Neil was, in return, a practical help, a protective presence and a patient model (for example, see Sleeping Nude and A Glasgow Lodging, above).

Described as charming and intelligent, Neil was also reticent and eccentric, with a volatile temper – already psychologically scarred. Eardley, too, was prone to a sharp temper and suffered from bouts of depression. Her father had also suffered shell shock after a gas attack during the First World War and died by suicide when she was eight years old. Moreover, she endured chronic pain in her back due to a slipped disc. They understood each other instinctively.

Despite their closeness, she delayed telling Neil she was suffering from breast cancer, possibly concerned about how he might react. Neil would paint The Last Supper shortly before she died. His doctor recalled him saying Eardley added the final touches to the painting – the yellow streak in the bottom right – 'taking a large brush, heavily laden with paint & drew it across the bottom in one sweep.' The expressive brushwork and religious theme are a dramatic departure from the quiet tonal realism of his earlier paintings. Coupling the subject's symbolic portent with the emotion of the two artists' impending separation, it must be Neil's most powerful work.

He is thought to have been working on other ambitious subjects at the time, which did not survive. 'Morrison got my house also Joans cottage the pub got Joans studio the wee cottage known as No 1 […] I lost all my things in 204 St. James Rd [Eardley's Glasgow studio] and No. 18 Catterline.' Neil was paid £30 for his cottage before it was demolished, but most of his personal effects were lost or destroyed. Accounts of these traumatic events, and various episodes leading up to his detention by the authorities, haunt his letters.

Carole Gibbons did what she could to support Neil during these difficult years, but came to a realisation: 'Angus had no intention of finding a room and he was finding it very difficult to paint. I realised he wanted to be in an institution. It was one sure way to get food.' Even though he resented being 'locked up', Neil admitted, 'I'm being kept alive by being here.'

Dundee Liff Hospital had art therapy facilities, where Neil painted a portrait of a fellow patient. His doctor there wrote to Mackenzie Smith in 1994, that 'he was often distressed but he certainly produced about half a dozen oil paintings […] & perhaps a couple of dozen pastels […] I am not sure what happened to these works of art. Certainly a few of the pastels were torn up, the pastels broken & stamped into the carpet in one fit of anger, but he did not destroy the majority.'

According to Neil, once he arrived at Sunnyside Royal Hospital in Montrose, 'the paintings were all cut up and used for dolls houses.' It seems, at times, he barely found paper for his letters. They were often on torn scraps, some cross-written on leaflets he'd taken from the post office, and one was on the back of documents stolen from an office in the hospital. 'I had to steal this paper if I were found out the consequences would be pretty bad'.

In 1977, after almost a decade without sufficient art materials or a place to work undisturbed, Neil was at a particularly low ebb. Frequent ward changes and regimented cleaning practices thwarted most attempts at creativity. When Mackenzie Smith became aware of Neil's predicament, he was able to secure funding for the artist from the Royal Scottish Academy and the Scottish Artists Benevolent Association.

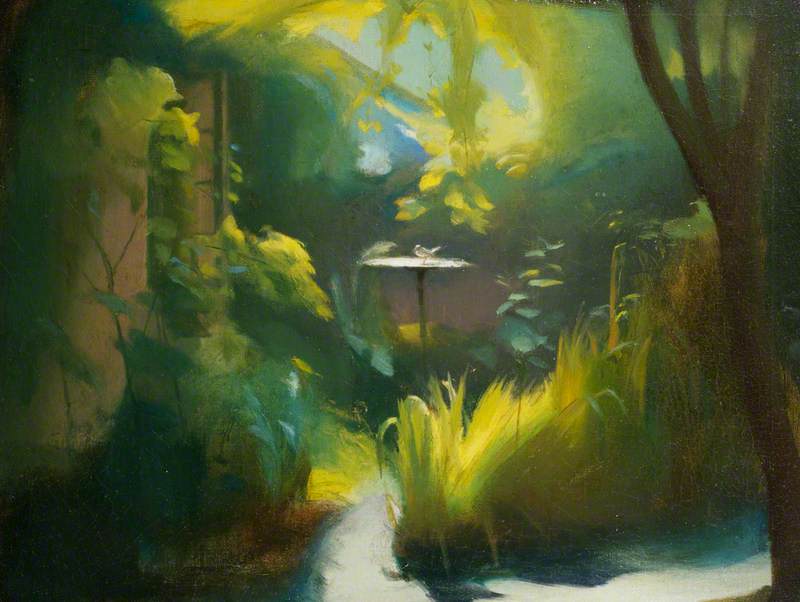

Around the same time, a hospital chaplain, Reverend Allan Downie, took an interest in Neil and commissioned a painting of the 'Feeding of the 5,000'. By 1983 he was painting The Birth of Jesus, an emotional turnaround from The Last Supper. It is clear that Neil was still deeply troubled. Many years later, he would still write anxious messages to the gallery: 'Joan died of breast cancer I want the bad painting Birth of Jesus back I will recompense you it was done here when I was seriously ill'. Nonetheless, he was now able to contemplate visible moments of serenity and optimism.

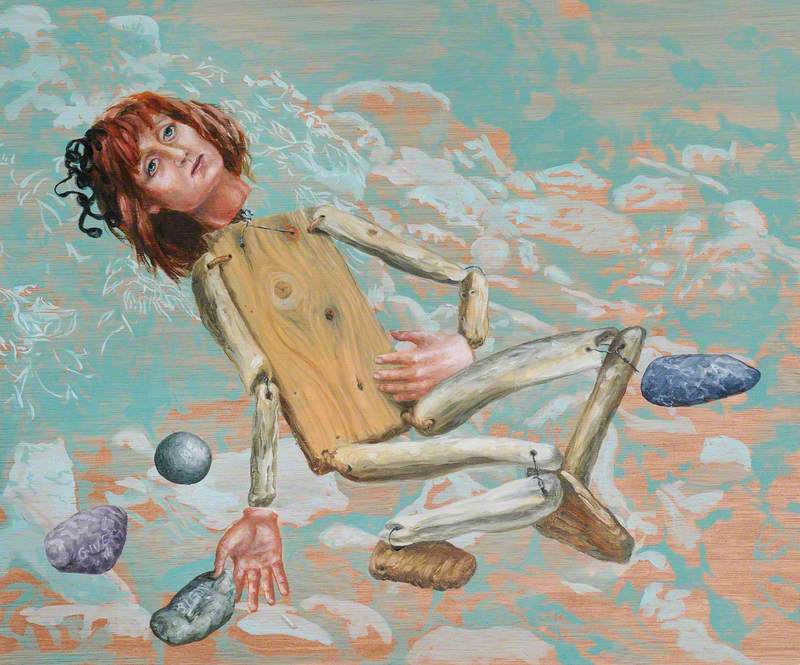

An Angel Ascending to Heaven

1969 & 1983–1989

Angus Menmuir Neil (1924–1992)

An Angel Ascending to Heaven, also referred to by Neil as A Saint Ascending to Heaven, was to him the most significant. Begun in 1969, he painstakingly reworked it over six years. He offered it to the gallery: 'Its Joan floating to Heaven and it was done a while ago but I got the wind up while doing it and didn't finish it its framed and signed.' A month later, he wrote again saying it was still unfinished. For the artist, it was truly a labour of love, expressing more through the layers of paint than he, or anyone, could hope to understand.

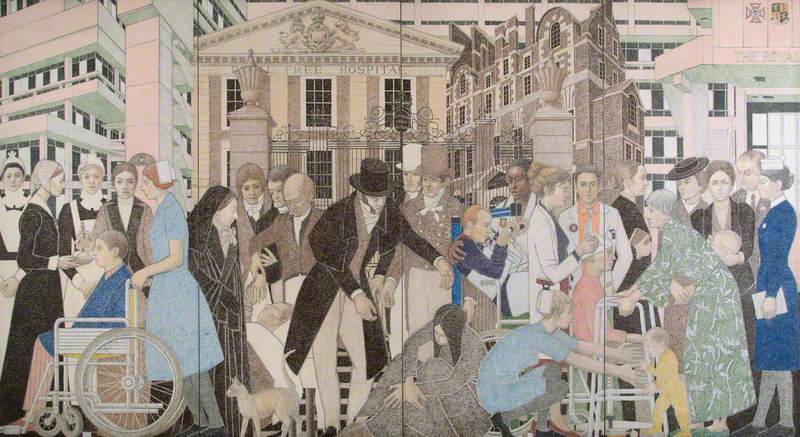

The body of art that has been created in UK mental health settings is extensive. The organisation Outside In, which provides a platform for artists who encounter barriers to the art world, has been working with partners across the country to raise awareness of these collections. By preserving, cataloguing and attributing this 'lost' art we can begin to restore the identities of those who created it, and raise compassion and support for those in mental care.

Anne Pritchard, freelance art historian and curator

This content was funded by the PF Charitable Trust

Further reading

Angus Neil Archive, Aberdeen Treasure Hub, Aberdeen Archives, Gallery & Museums

Griffin Coe, 'Friendship in focus: Joan Eardley and Angus Neil', Aberdeen Archives, Gallery & Museums

Henry Guy, Angus Neil 'The Quiet Man', unpublished, 1995

Ian Mackenzie Smith and Cordelia Oliver, Angus Neil (1924–1992) Paintings and Pastels exhibition catalogue, Aberdeen City Council, 1994

Fiona Pearson, Joan Eardley exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, 2007