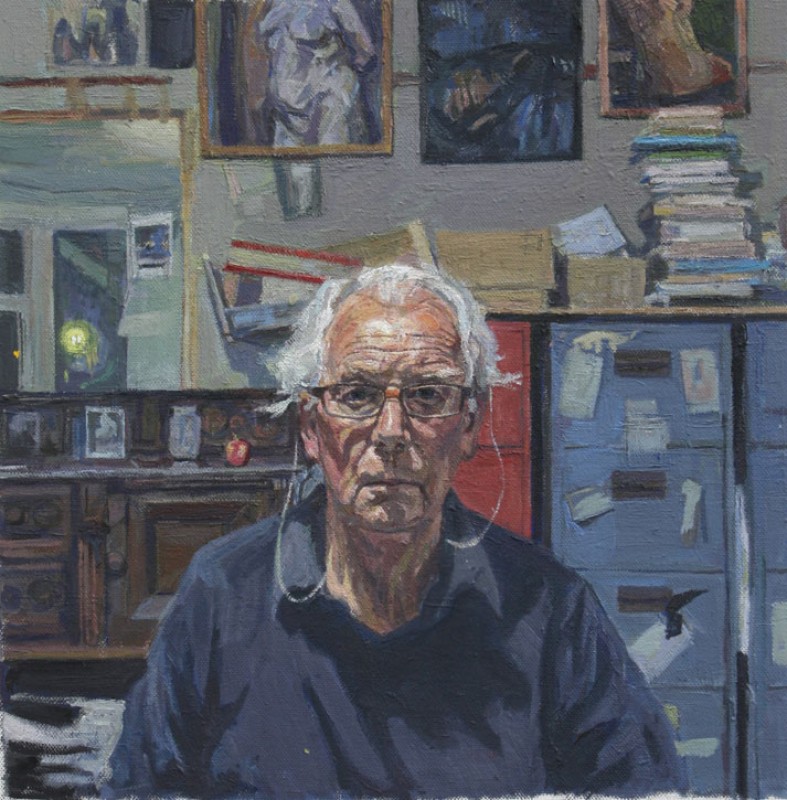

When curating an exhibition of an artist as famous as Frank Auerbach (1931–2024), the challenge is to say something new about his life and work.

The galleries at Newlands House Gallery are a great setting for the work as they are at a domestic scale. The intimacy afforded to viewing art in this space beautifully reflects the subjects in the work. We have pulled out of storage his drawings that are energetic and full of creative confidence.

Installation view of 'Frank Auerbach: Unseen'

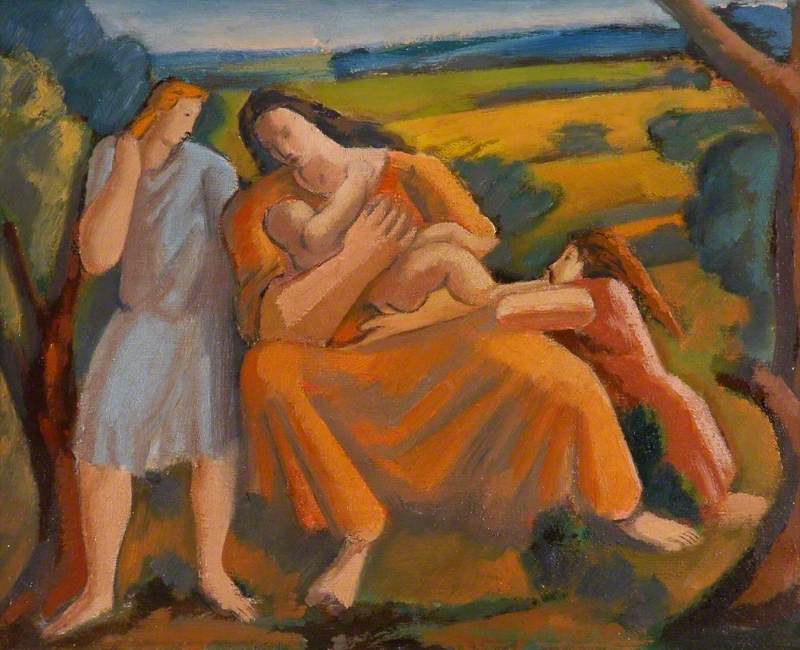

We have also paid homage to the collector, David Wilkie, a modest man whose passion for art led him to spend his life surrounded by art and artists. The show builds a portrait of Auerbach looking at his own process, his various sitters, and friends.

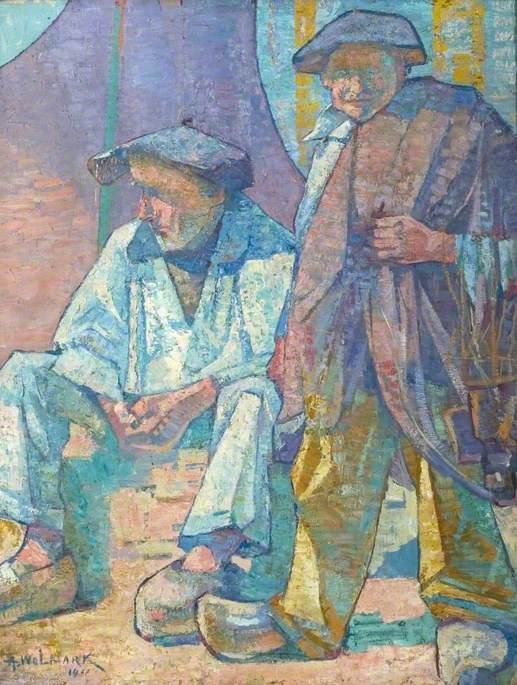

Through a selection of drawings and paintings, we have visualised how his work has developed through the years, galvanising his reputation as one of Britain's most important living artists. To view the show is to enter Auerbach's world: pensive, intense, delicate and human.

Auerbach was born in 1931 to a Jewish family in Berlin. In 1939, he arrived in England when his school relocated to Bunce Court in Kent. The school catered mostly to Jewish families and Auerbach's parents were happy with the move as there were no restrictions on Jews in England as there were in Germany in 1939. Auerbach was 8 years old and by 12, he already knew that he had been orphaned when the censored letters from his parents stopped arriving through the Red Cross. They were both murdered in the Holocaust. He moved to London when he was 16, just a boy, with very little support and almost no money.

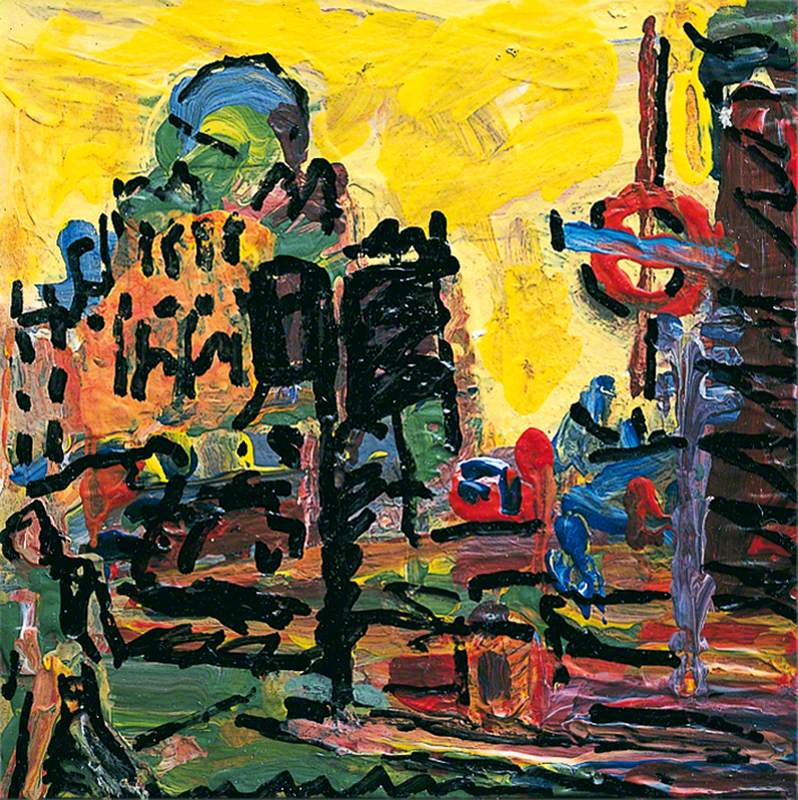

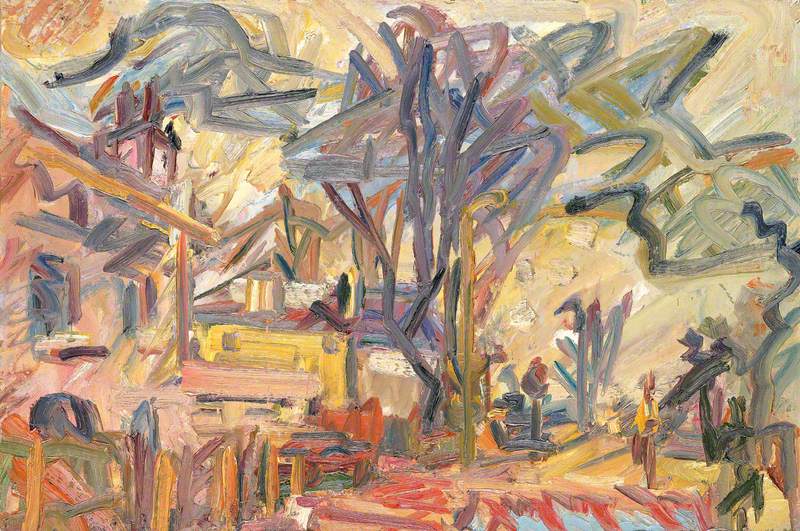

Building Site, Earls Court Road: Winter

(replica) 1955

Frank Helmuth Auerbach (1931–2024)

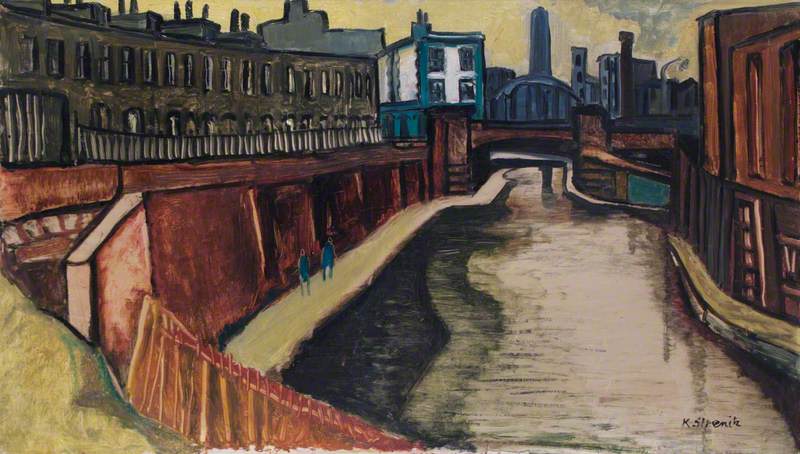

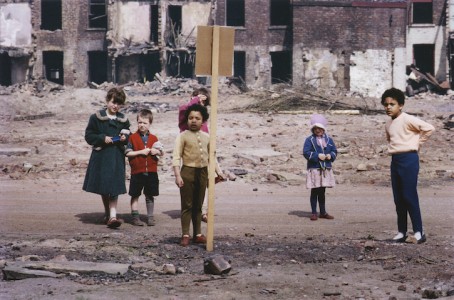

London in the late 1940s looked very different to how we experience it today. Not only because of the developments in technology, design and fashion, but because London endured so much bombing by the Luftwaffe during the Blitz (1940–1941). The city was a ruin, filled with rubble and craters.

One in every six Londoners was made homeless and over a million residential buildings were damaged or destroyed. In the eight months of attacks, some 43,000 civilians were killed. 'There was a scavenging feeling of living in a ruined town,' Auerbach recalls in his biography, in which he describes a sense of humility in having survived.

Intent on not having an office job, Auerbach briefly flirted with the idea of becoming an actor, but art finally won him over. A young artist sensitive to his surroundings, he found the city in its current state fertile material for his art. He began by painting the regeneration of the city, focusing on the many building sites, cranes, and scaffolding springing up around him.

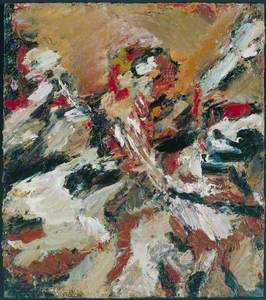

There is a sense of foreboding in his early works – a darkness that reflects the mood of the time – but also a sense of hope, like a phoenix rising. His fascination with London would accompany him his entire career. Now in his 90s, the sum of Auerbach's cityscapes equates to a moving portrait of a city – from regeneration to new life.

After his move to Camden in 1954, Auerbach would limit his cityscapes to his immediate surroundings, painting Primrose Hill, Mornington Crescent, and the buildings of Camden – repainting the same views again and again. He is an artist in search of something intangible in his work that requires constant repetition. When found, the labouring never seems laborious. His work seems fresh and current, describing an encounter and immediacy with a presence or tension, indicated by an occasional cyclist or Underground sign.

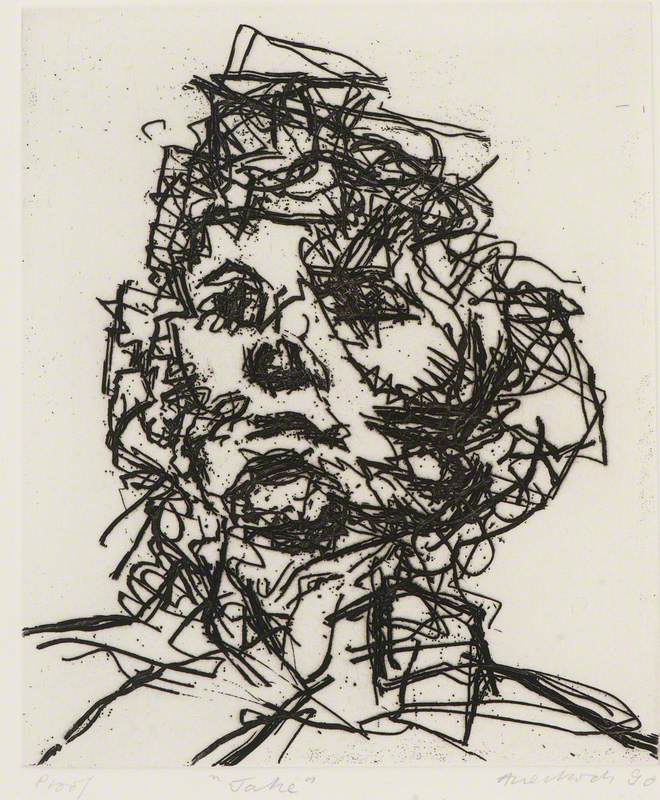

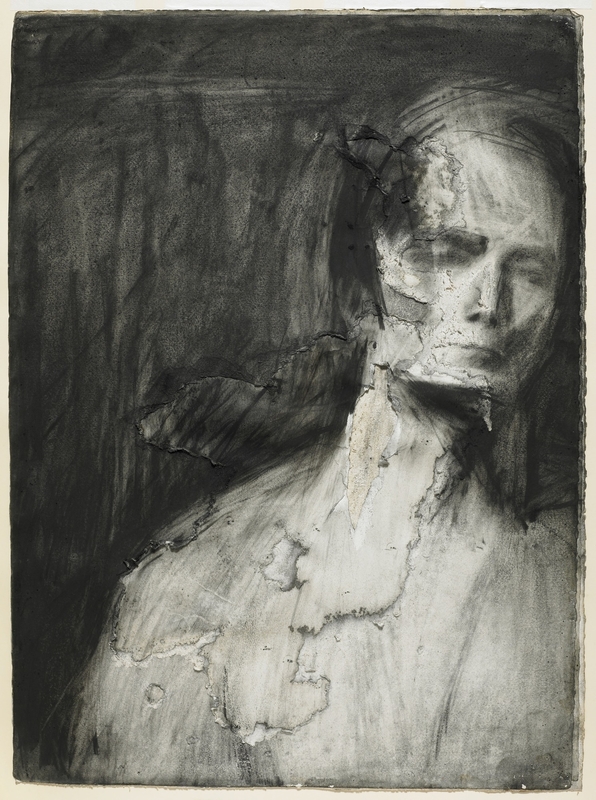

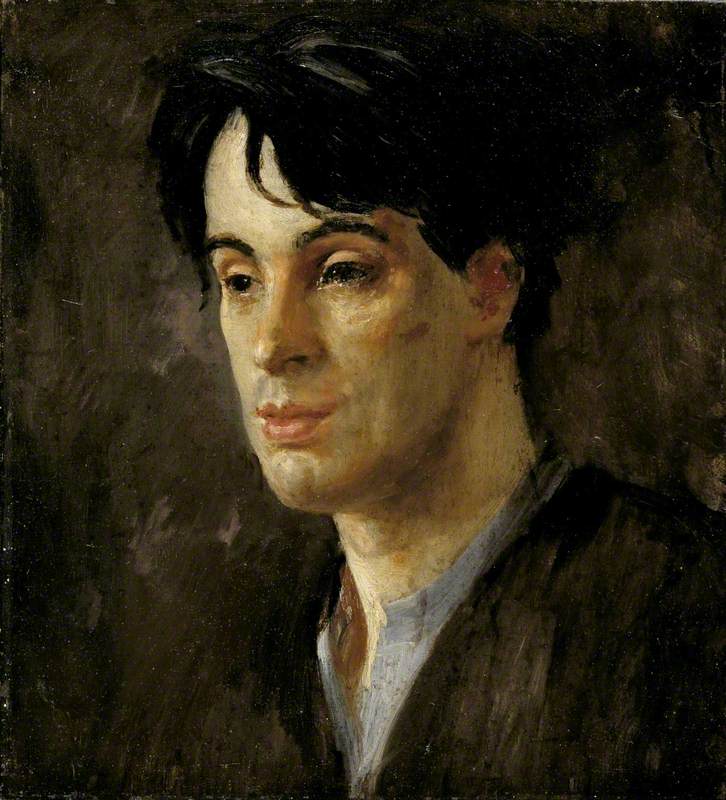

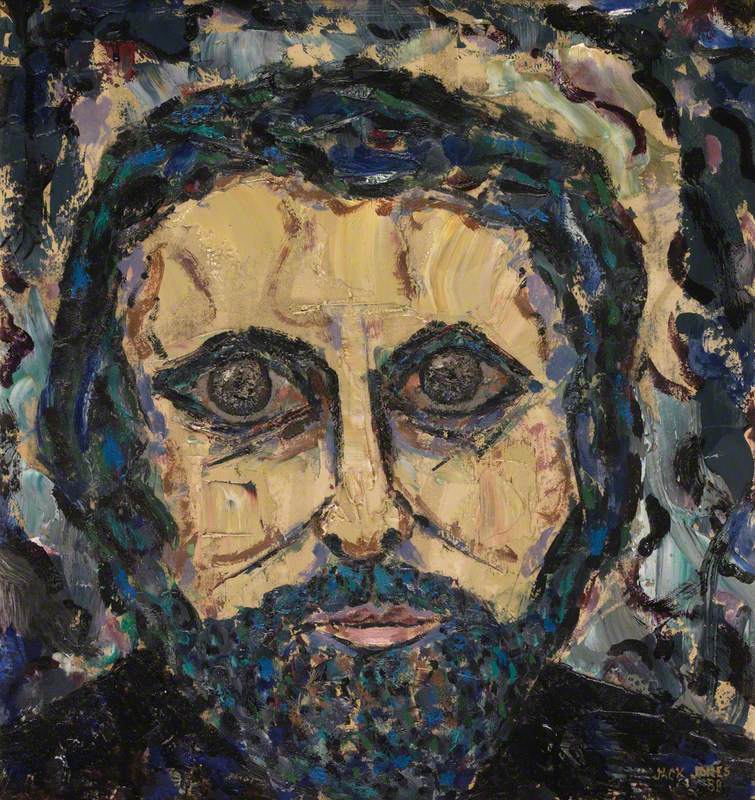

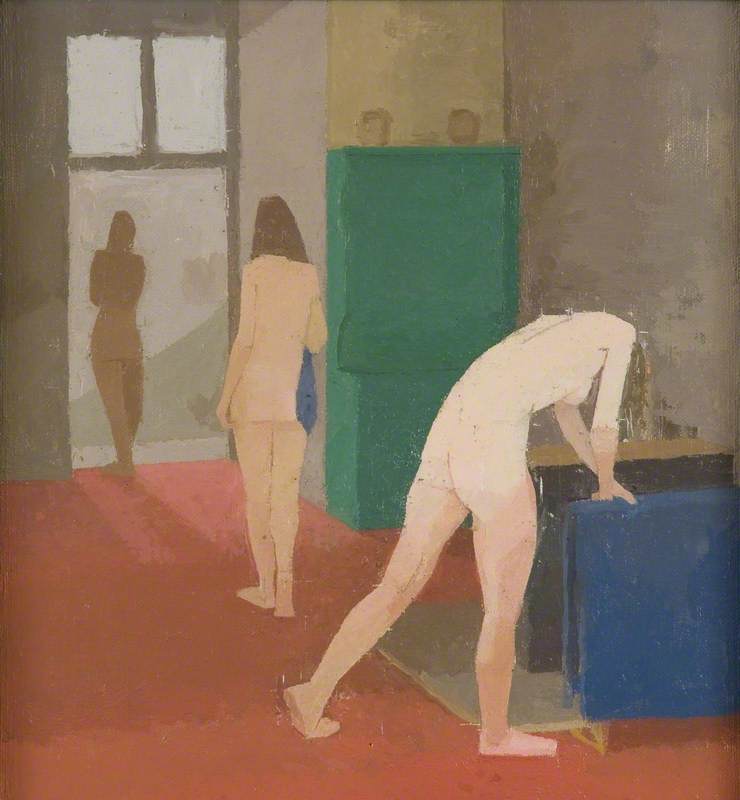

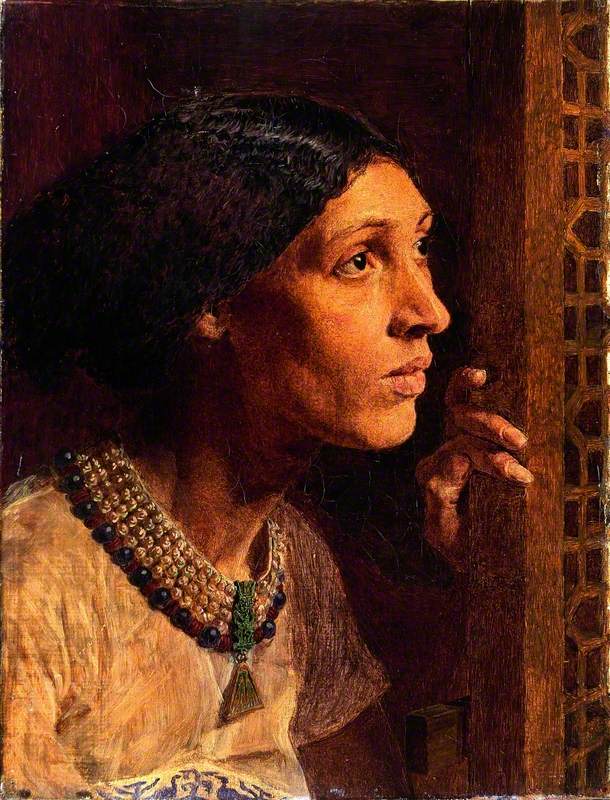

This is particularly evident in his portraits, which have an almost mythical status. Sitting for Auerbach has become part of the artist's legend. His sitters, who have included his wife, son, lovers, friends, and fellow artists, need to regularly commit to Auerbach, as a painting can take months, if not years. Catherine Lampert, his biographer and curator, has been sitting for Auerbach regularly for over 16 years in the same position. Estelle Olive West (referred to E.O.W. in the titles of the paintings and when spoken of) sat for Auerbach from the early 1950s to 1973.

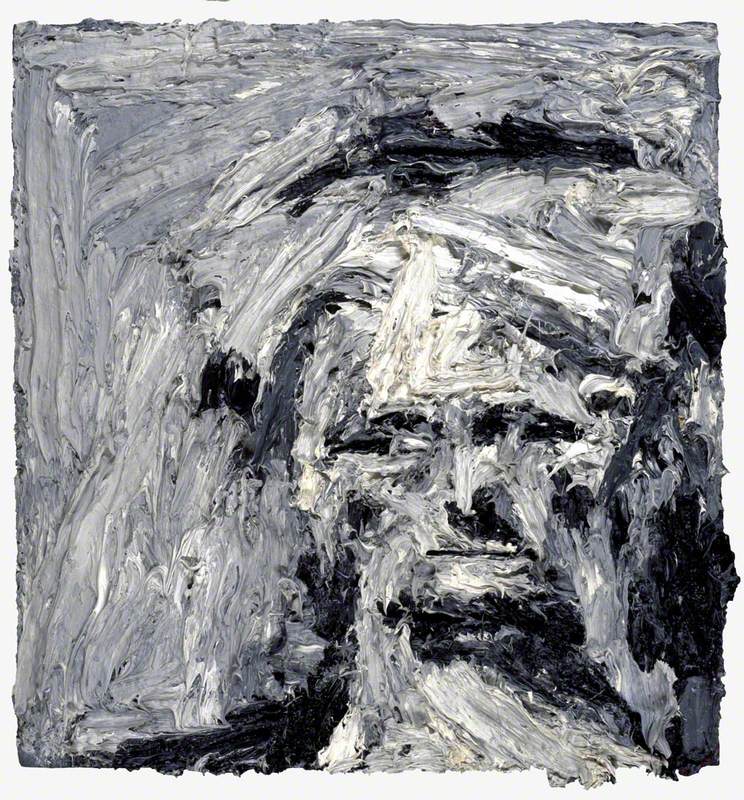

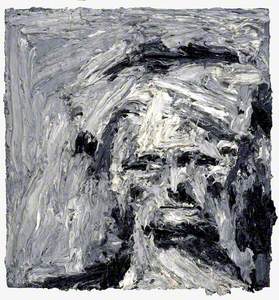

Auerbach knows his sitters well. He has spent many years observing them, perceptive to their changing moods and postures. Auerbach will never ask a sitter to 'pose', preferring an honest arrangement of how the individual will choose to position him or herself. To look at an Auerbach portrait is to witness a relationship. It can make for uncomfortable viewing at times as we enter an intimate space of artist and model. As the works have become more abstract and loose in his later years, nothing is lost from the intensity of observation. The sentiment is still there, even if a clear head and mouth aren't.

In artistic circles, he is famed for his monastic dedication to his art. He rarely travels, choosing to spend seven days a week in his studio. Returning to Germany as an adult, he described it as 'uneventful'. One can assume that the artist finds comfort in his routine.

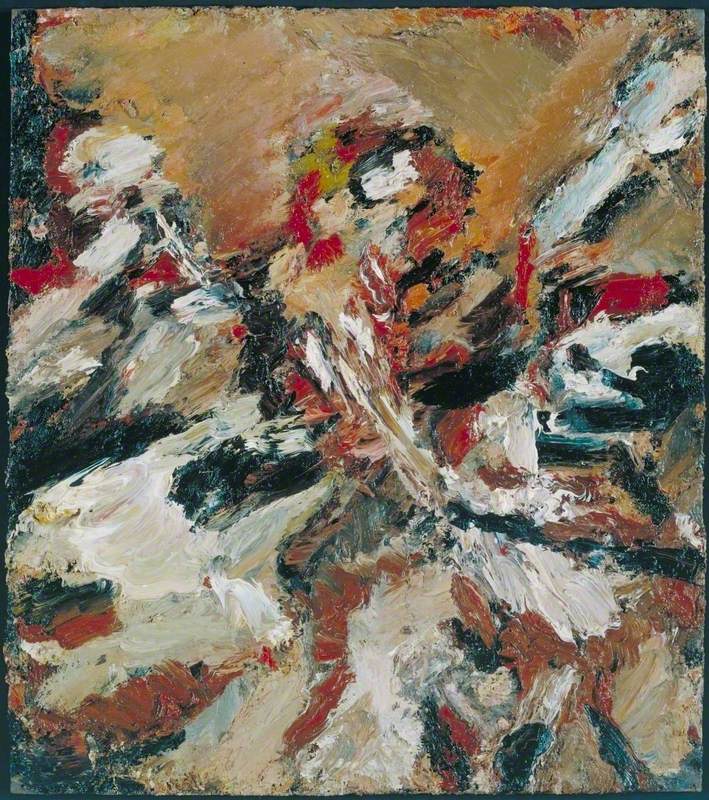

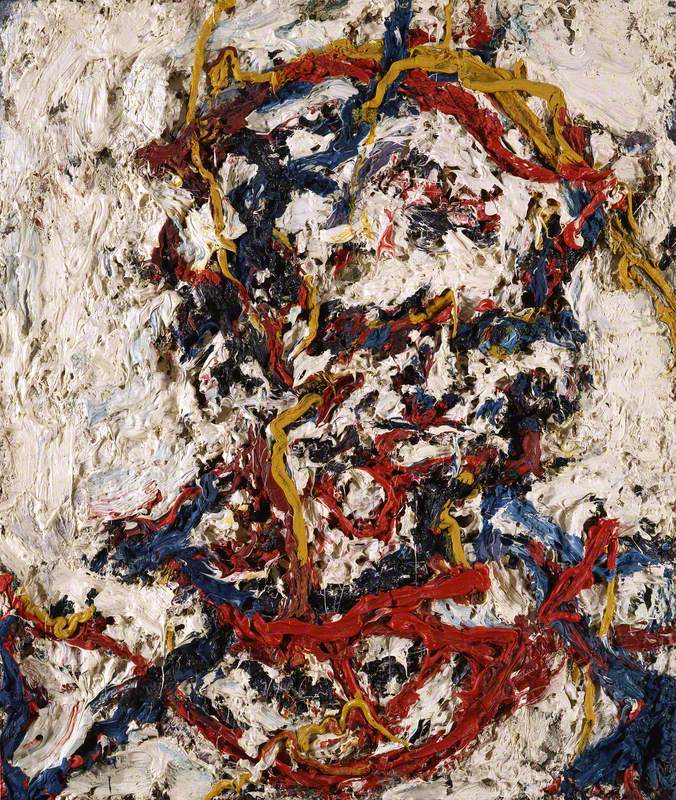

His technique, however, has developed and changed throughout the years. Where in the past he would overpaint his previous works, creating thick layers of impasto to the point where it seemed the paint might fall off the surface, Auerbach will now scrape off the paint before trying again to find a successful painting. He claims that in the past he was too poor for such an obviously wasteful approach. As his wealth increased, and his confidence, so did his budget for pigments, as seen in his later works, which yield more vivid colour in the texture.

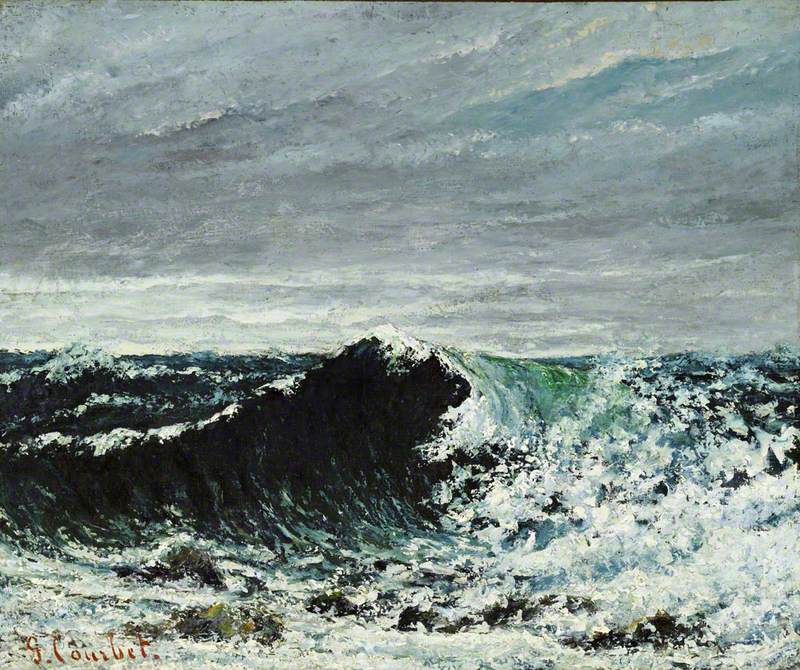

Though it isn't always clear, Auerbach has been hugely influenced by the artists of the past. He was particularly drawn to the art of the British masters such as J. M. W. Turner, John Constable, Thomas Gainsborough, and Joshua Reynolds.

Preferring to draw directly from the original work, Auerbach would spend hours in The National Gallery, sketching in felt and colour. These 'notations' would then be used by the artist back in the studio to inform the structure of his paintings.

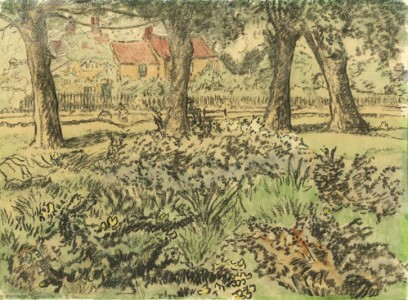

Park Village East, Winter

1998–1999

Frank Helmuth Auerbach (1931–2024)

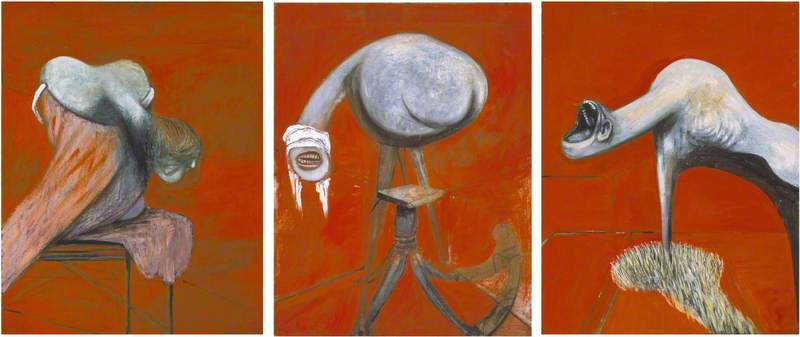

He was also influenced by the people around him – for example, Francis Bacon, who convinced him that his paintings should always be glazed to separate the viewer from the work and so that one could see them as a whole.

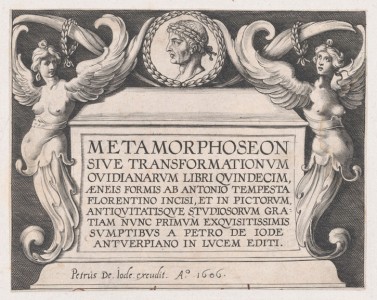

Collector David Wilkie was another such influence who commissioned some extraordinary works of Auerbach, such as The Origin of The Great Bear, where Auerbach reimagines Ovid's Metamorphosis as a scene on Hampstead Heath. The story of how Callisto and Arcas get transformed into star constellations now features the Royal Free Hospital. Jupiter is in the form of an eagle top left.

In his art, Auerbach has set himself tasks that he describes as 'impossible': that of trying to create something new and to create something great considering art history. Realising the impossibility of this undertaking, his resolution is Beckettian to 'Try again. Fail again. Fail better.'

Maya Binkin, curator and founder of The Art Pilgrim

'Frank Auerbach: Unseen' is open at Newlands House Gallery, Petworth until 14th August 2022

Further reading

Catherine Lampert, Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Talking, Thames & Hudson, 2015