Euan Uglow (1932–2000) was an obsessive painter of the human body at a time when doing so placed him at the centre of a contentious debate about what art could and should do. Modernism impacted the British painting scene in the early twentieth century, bringing with it the search for a new visual language that could communicate a radically redefined human experience in the wake of mass industrialisation, urbanisation, consumerism and technological growth.

Many artists met this challenge by pushing the bounds of abstraction or dematerialised art forms, such as performance and conceptual art. Uglow was, however, amongst a loose community of artists from the rising post-war generation, often referred to as the School of London, who turned instead to the unsettling power of the human body.

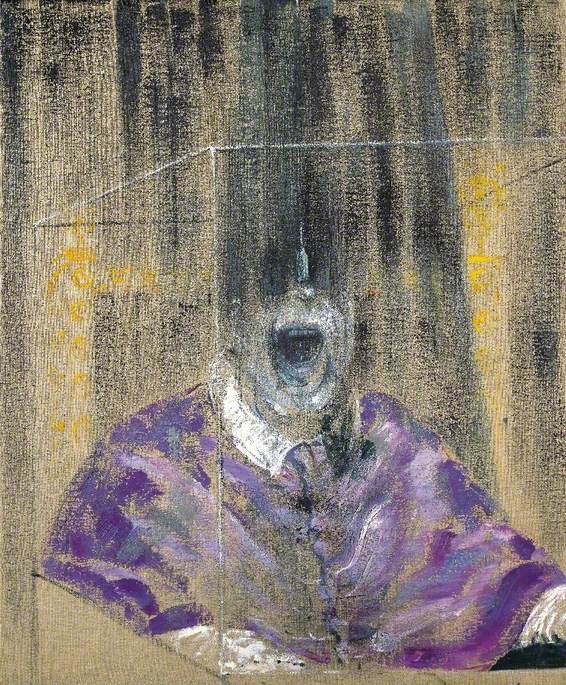

Uglow chose subtlety and gravitas over the twisted sinews of Lucian Freud, the congealed skin of Frank Auerbach or the collapsing exoskeletons of Francis Bacon, and his bodies are no less a symbolic meditation of how the rules of painting can be wielded to reveal the human condition: in Uglow's case, the personal nature of visual experience.

Uglow began his painting career as a precocious 15-year-old, when he enrolled in Camberwell School of Arts in 1948. It ended suddenly (and at 68 years old, too early) after a brief illness in 2000. Over the course of this 52-year period, his subjects and preoccupations remained consistent: the human body and anthropomorphised still lifes, which were carefully positioned and represented, alongside a smattering of small landscapes, which he dashed off during his travels.

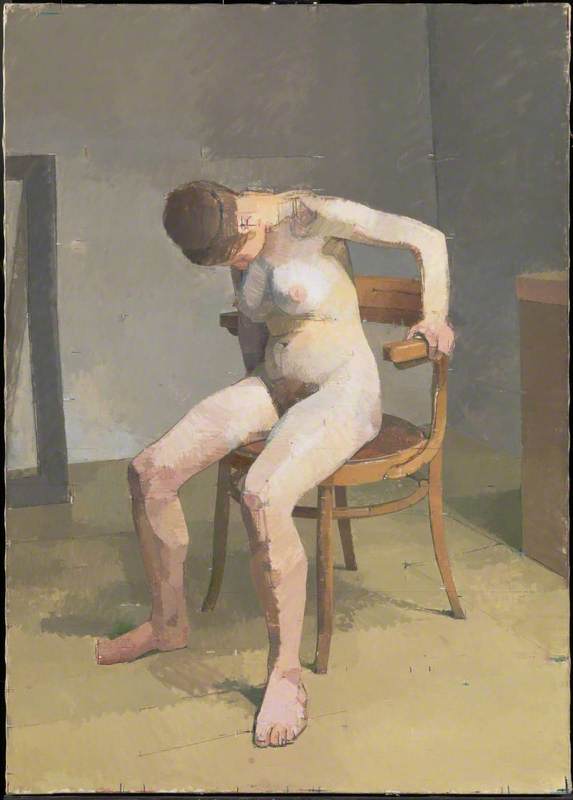

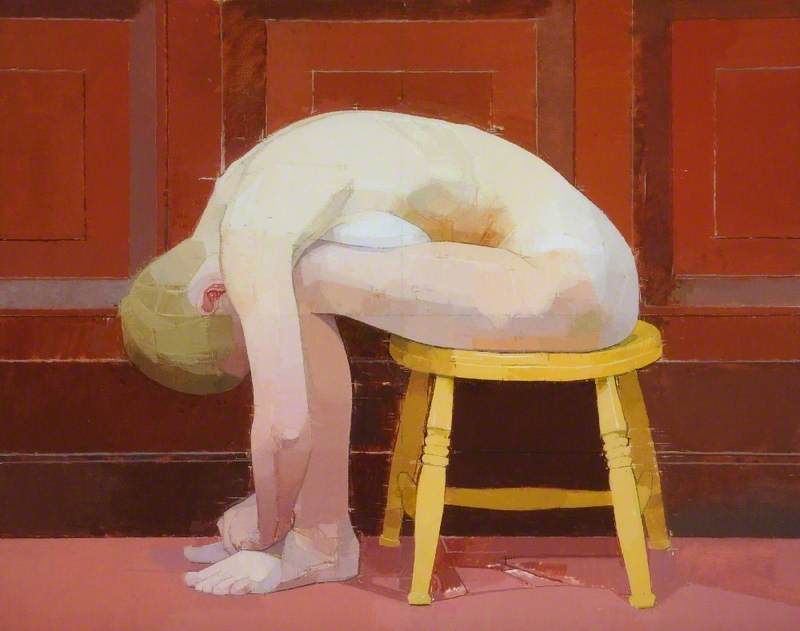

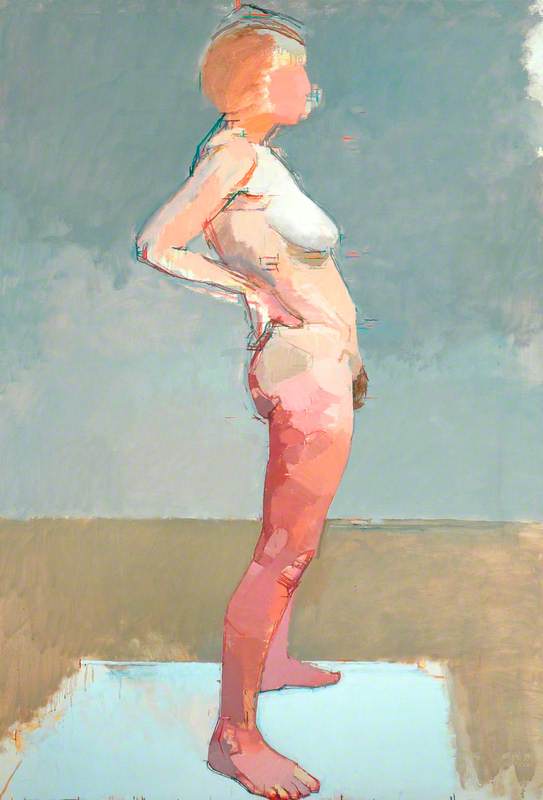

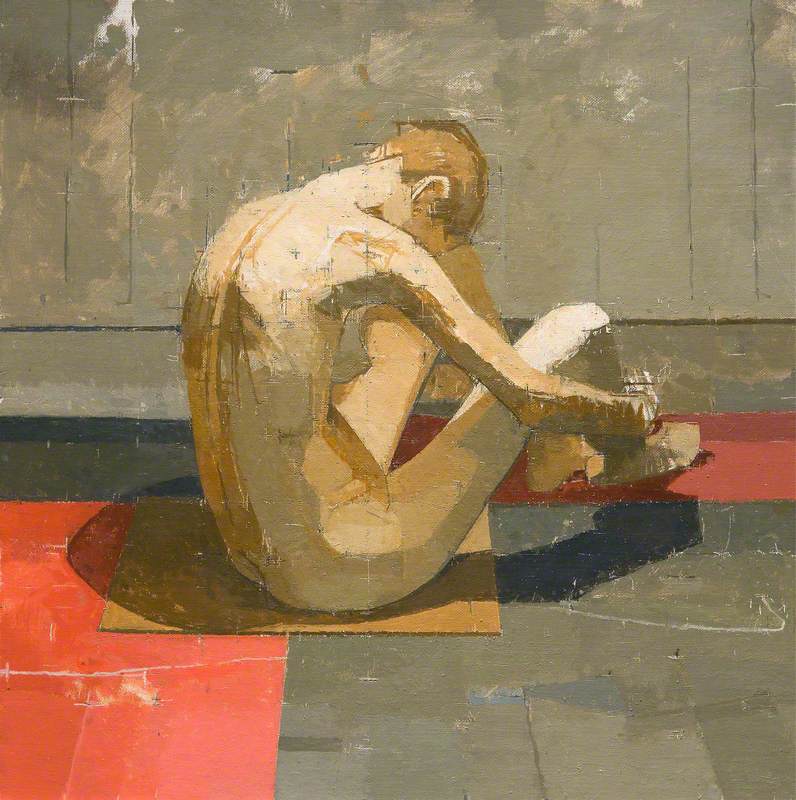

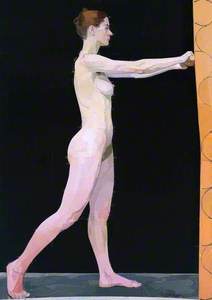

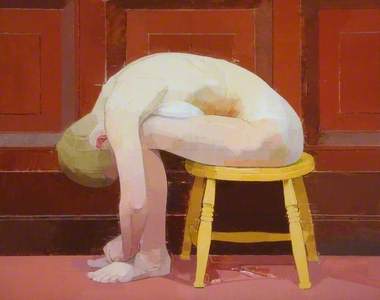

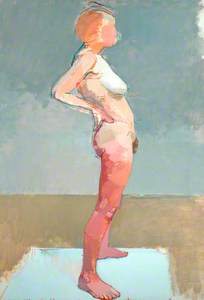

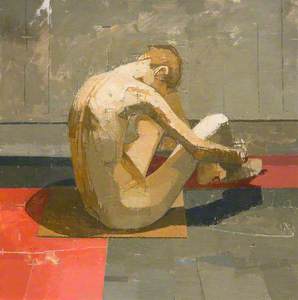

Subjects, usually nude women, are placed close to the picture plane. They almost always look away: Uglow did not like to be watched as he worked nor to be influenced by his model's inner world. And the environments around his subjects were carefully constructed, which included his crafting the furniture, scaffolds and platforms – creating what Uglow called his 'set ups'. Even in a seemingly simple composition such as Curled Nude, he created the stool from a chair because of the double-frame structure of the legs.

Uglow's canvas shapes were also custom-made according to precise geometric requirements. Models came for three-hour sessions over the course of years. His method of painting, however, is most famous: Uglow relied on comparing fixed points on canvas with corresponding points within his set ups (often using measurements drawn onto props or hung plumb lines). The relationships between these points were established by measuring relative distances through vertical and horizontal lines, slowly building up the picture like a map.

Colours are kept clean and saturated through frequent brush washing and carefully balanced hues (Uglow's skill as a colourist is often under-appreciated). The result is an oddly enigmatic otherness, where great stretches of time are compressed into these intense and deceptively simple scenes.

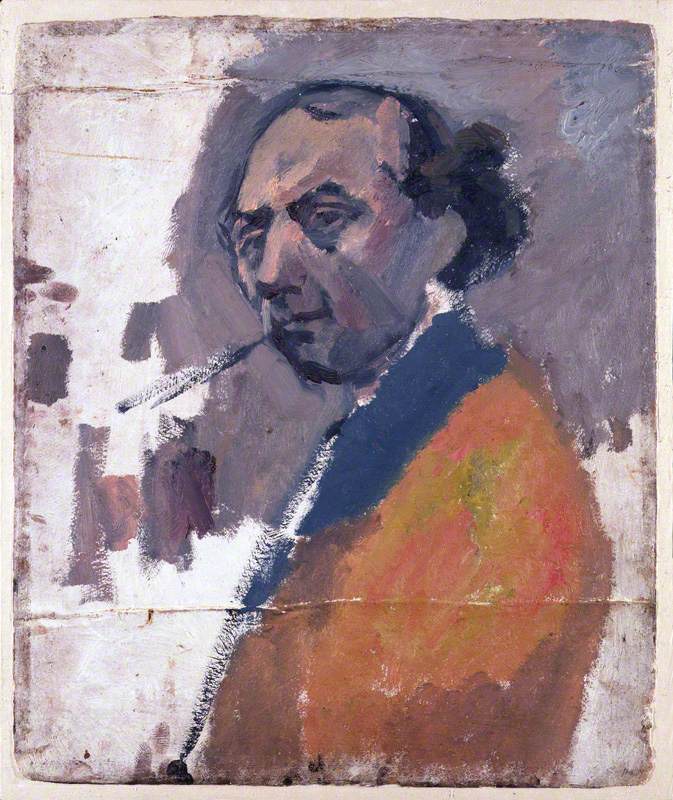

Uglow developed his approach during his studies at Camberwell between 1948 and 1950; the first of his canvases to showcase measuring marks appeared in 1949. At Camberwell, he came under the influence of a coterie of teachers who had been prominent interwar realist painters at the Euston Road School, foremost among them William Coldstream.

Coldstream had developed a method of painting that will sound very familiar: working slowly over years with the same model, measuring between fixed points that are built up like a crossword resulting in a picture that collapsed time into a single uncanny image, from which measuring marks in the form of stars and barbs interpose themselves between viewer and subject.

The goal was to test the distinction between seeing and thinking. Each painting was an experiment in probing what remained if an artist avoided the traditional recourse to foreknowledge in the form of, say, memory, overt emotion or imagination.

The method became emblematic of the Euston Road realism, gaining the ironic name of the 'Camberwell easy', and once Coldstream moved to the Slade in 1948, it became known as the new 'Slade Style'. Uglow, along with many Camberwell students and teachers, followed Coldstream to the Slade – Uglow made the move to study there in 1950.

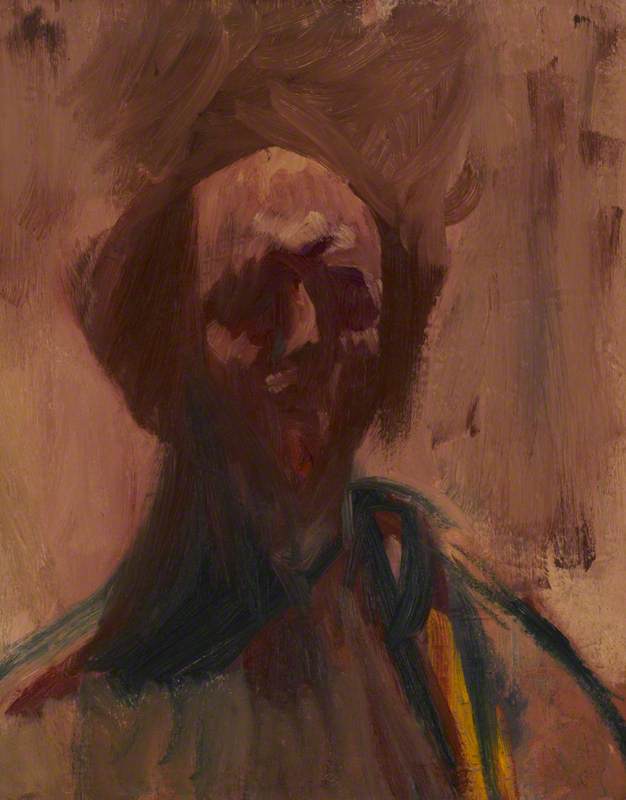

Girl's Head in Profile with Cap on

1963–1964

Euan Uglow (1932–2000)

There are many parallels between Uglow's and Coldstream's approaches and aesthetics – a conflation that has harmed Uglow's legacy – but there are also key differences. Coldstream was uninterested in geometric equivalents as well as in clean planes. His layering of multiple sittings blurs the changeable features of a model's lips and eyes, creating something elusory and fragile, whereas his measurement marks seem violent, as if the canvas were scraped raw and bleeding.

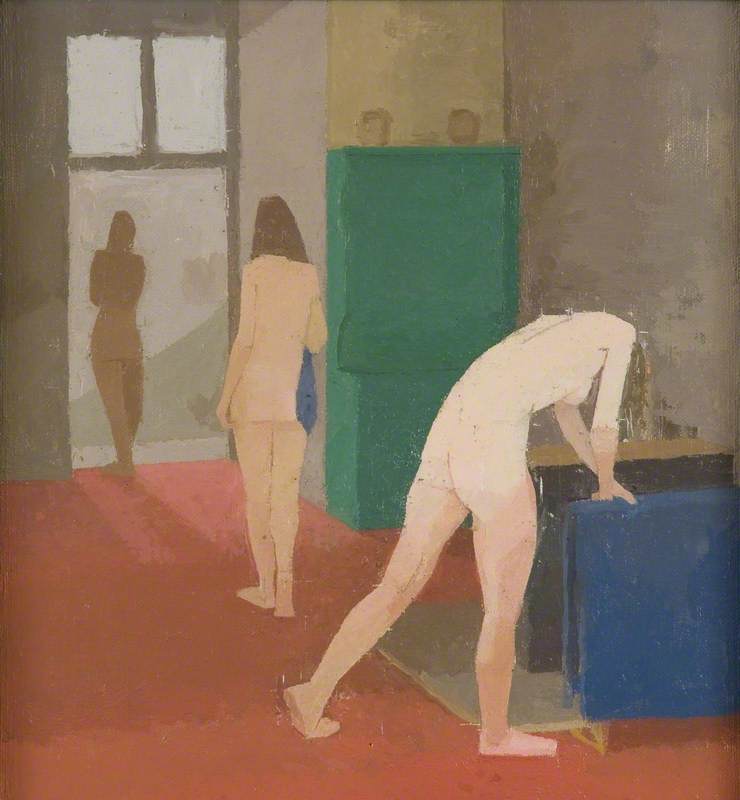

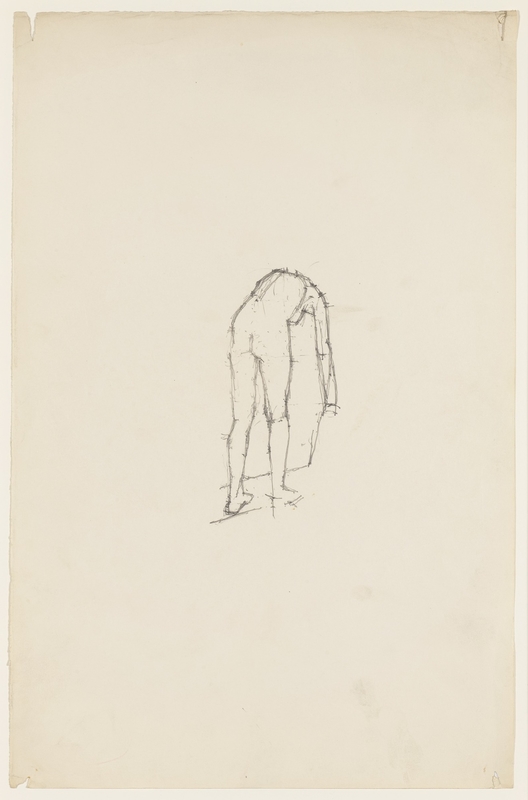

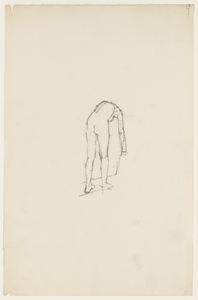

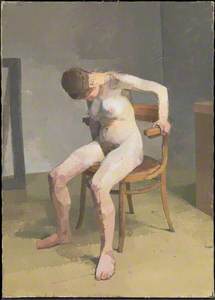

Uglow's painted world is cleaner, more precise, ruled by rationality and meticulous design, as seen in his 1982 work The Blue Towel. It is an unusual piece in that Uglow constructed it from drawings, such as this pencil study of his model, the artist Liz Barratt, as she picks up a towel – both pictures, lent by the Jerwood Collection, are currently on display in an exhibition of Uglow's work at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert in London.

The cleanness of the drawn lines demonstrate how Uglow used measuring as a means to an end. Unlike Coldstream, who dissolved his subjects' three-dimensionality into a mesh of notational markings, Uglow uses it to define clean forms. Time too is compressed in The Blue Towel, but it is both playful and serene. Liz appears three times – picking up her towel, walking to the shower and entering it – but each image retains a monumental stillness.

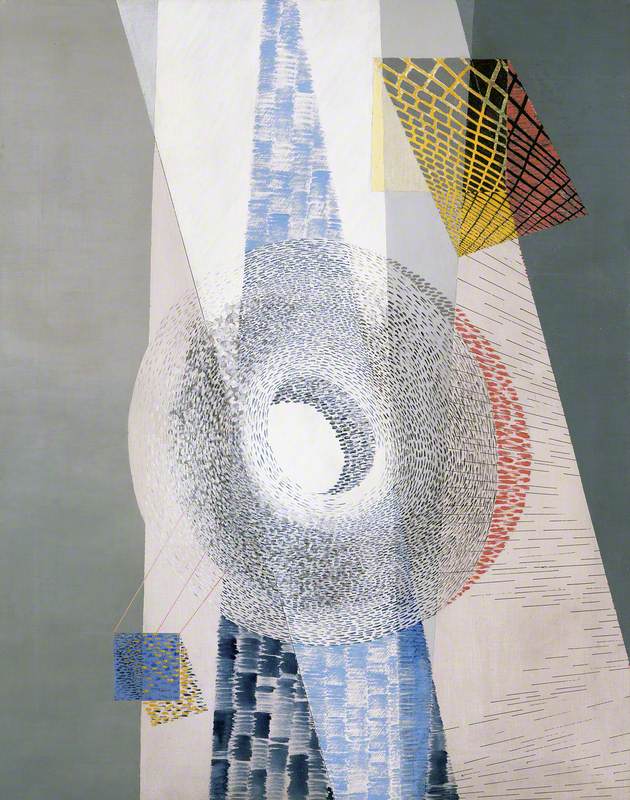

The echoes of other Camberwell teachers are evident. Victor Pasmore and Claude Rogers were fellow Euston Road realists working at Camberwell, though Pasmore enthusiastically (and controversially) turned his attention to formal abstraction in 1947. Pasmore tried to convert the young Uglow. He was not successful insofar as Uglow remained wedded to figurative subjects, but the importance of colour and composition for Uglow suggest that he was not immune to Pasmore's teachings.

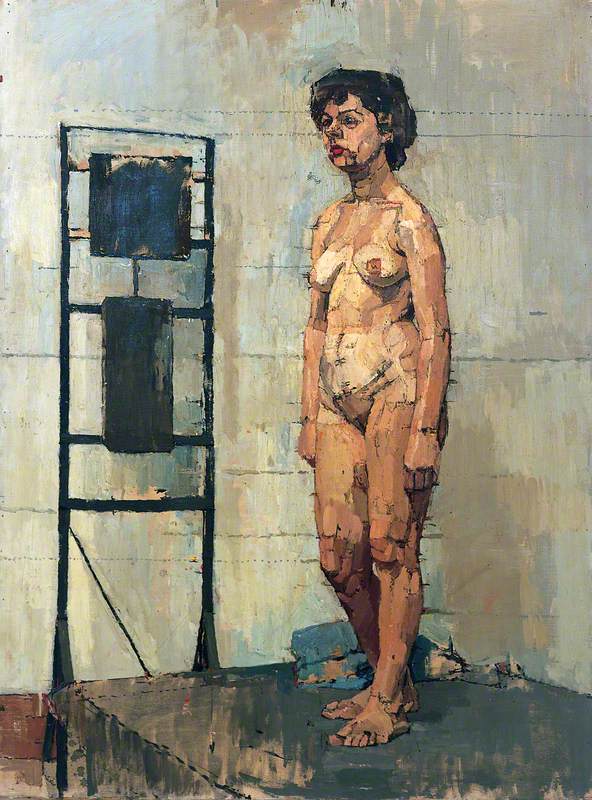

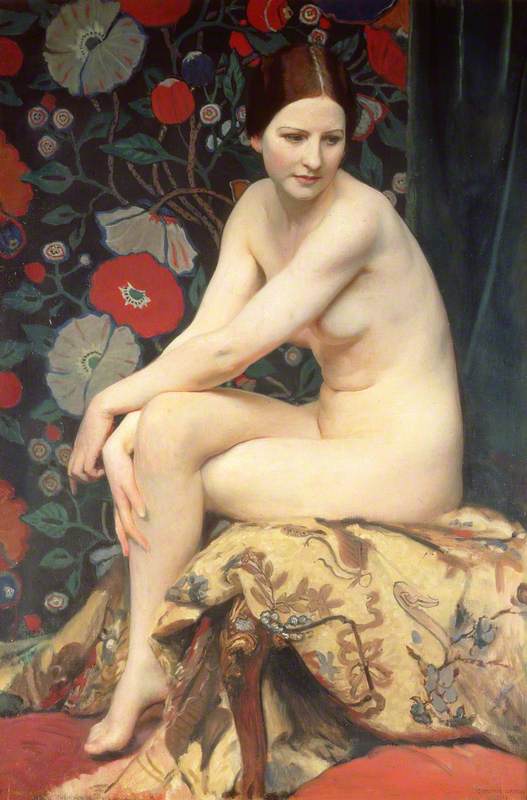

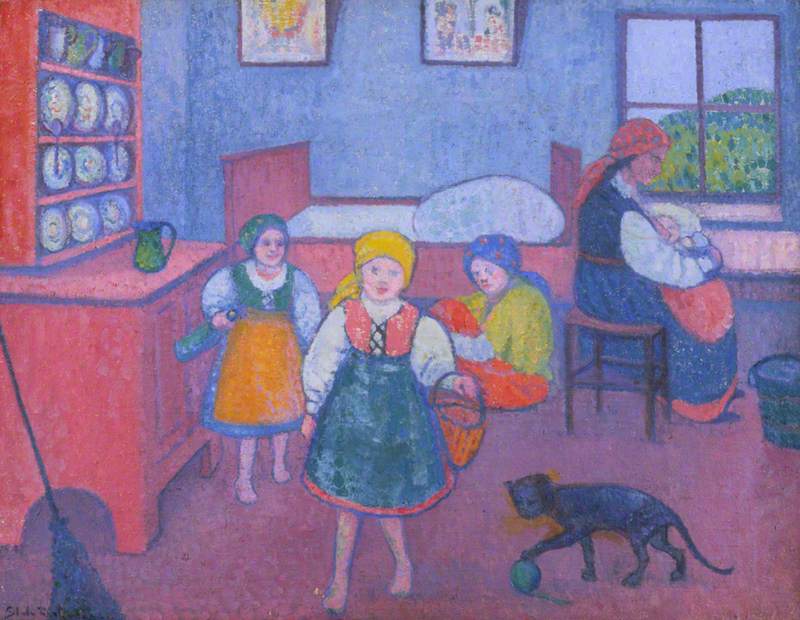

To Rogers, Uglow has attributed the greatest influence – though some historians have challenged this as an overstatement and an attempt to break his association with Coldstream. Rogers did have a cleaner palette and greater interest in structuring the surface of his painted subjects. In Miss Lynn, for instance, measurement is not the object but the means to understanding a carefully composed and ordered world.

As much love is given to the cradling white shapes of wainscotting and day bed as is invested in the delicate geometry of the sitter's cheek.

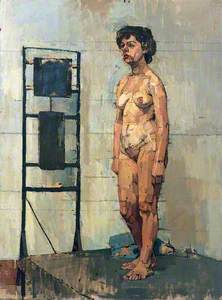

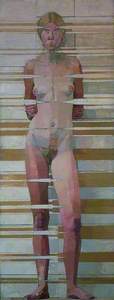

Uglow was certainly interested (possibly obsessively so) in how things really appear, but this emerges in mature work as a means to create an ordered world more than to aspire to objectivity. Uglow even made a picture, Nude, 12 Vertical Positions from the Eye, poking holes in the accuracy of Coldstream's method.

For this work, Uglow built a movable platform so that every time he painted one of the fixed points on his model's body, he raised or lowered the platform so that his eye was level with that point and thus he was able to view each one straight on. This negated the naturally curved nature of vision, accentuated when one is measuring horizontals and verticals by balancing a paintbrush on an outstretched arm.

The result was a pronounced elongation of the model and little wedges that could not be made to line up, appearing as if her body were an orange peel squished onto a flat surface – a common problem for cartographers.

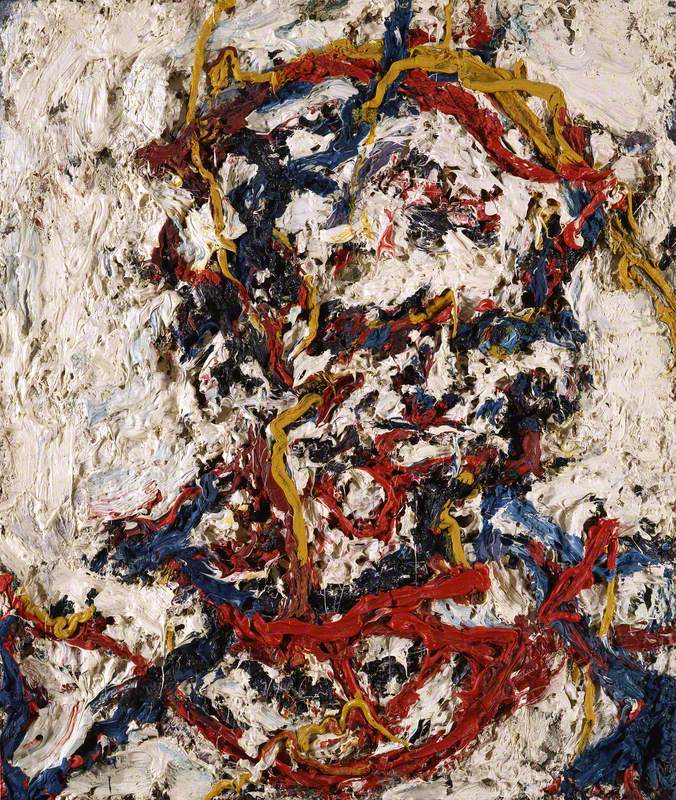

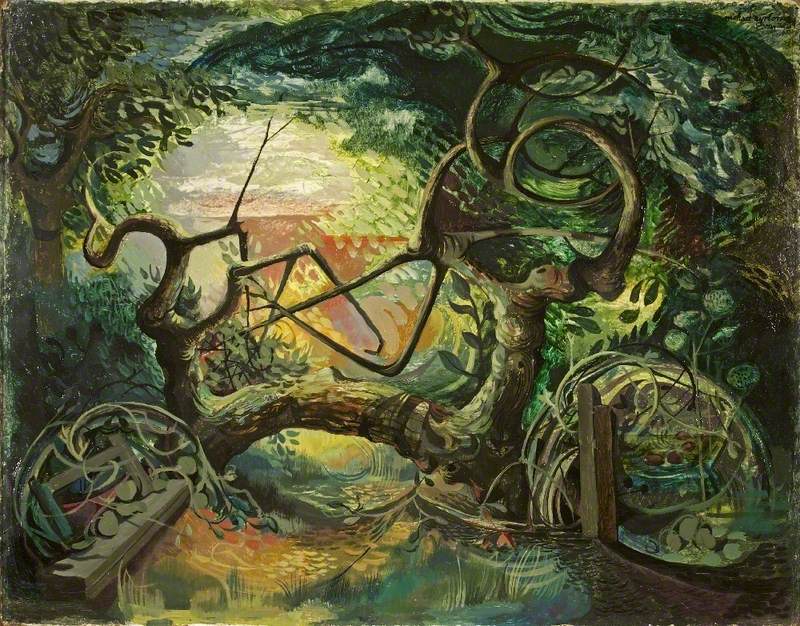

Contemporaries of Uglow were interested in the fallibility of the visual experience. Philosopher Ernst Gombrich, for example, claimed that the interpretation of raw visual data was socially constructed. A rival teacher to Coldstream, David Bomberg encouraged his students (including School of London heavyweights Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff) to experiment with the phenomenological theories of the eighteenth-century Irish philosopher Bishop Berkeley by doing away with linear perspective in favour of creating something more immediate and haptic.

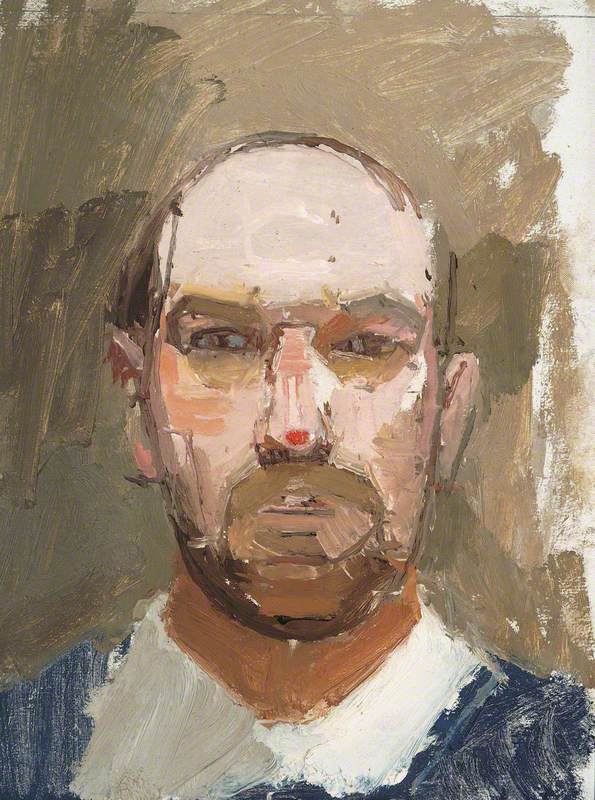

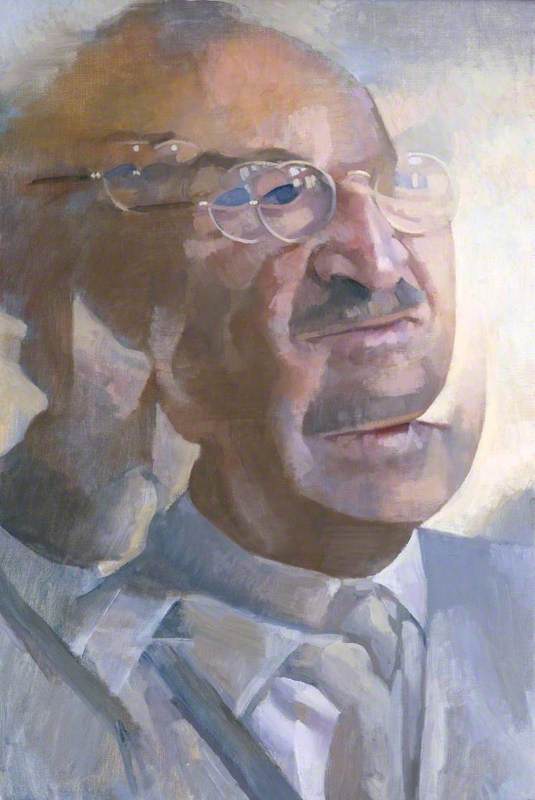

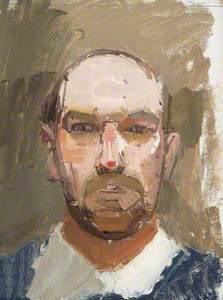

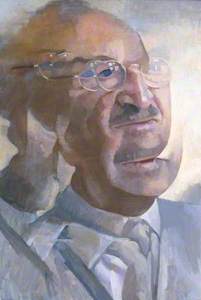

A former Euston Road pupil and eventual successor to Coldstream as head of the Slade, Lawrence Gowing also experimented with the shifting and doubling nature of binocular vision, in works such as Portrait of Sir Norman Reid.

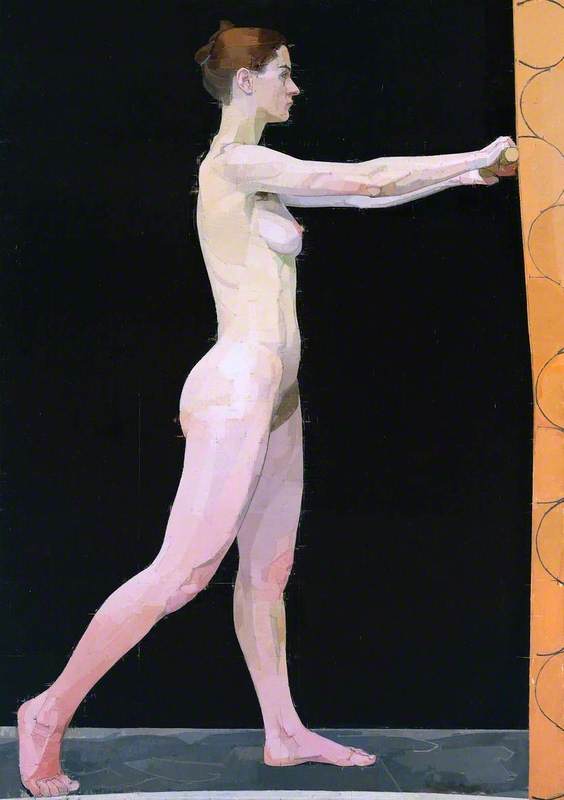

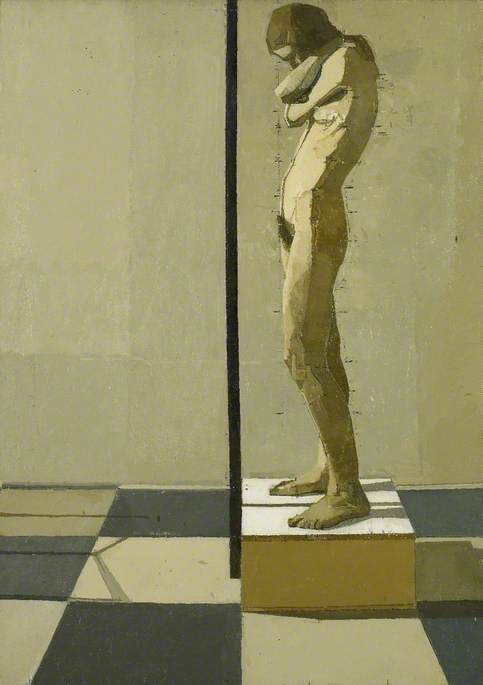

What makes Uglow unusual is that he combined Coldstream's rigour and empiricism with a love of the forbidden resources of perspective and proportion. In a painting such as Snake from 1976 we can see his simultaneous creating and collapsing of pictorial space.

The scene is deceptively simple: a young woman stands hugging her chin, her weight shifted into contrapposto. She stands side-on to the viewer upon a squat platform. Its edges are aligned with the borders of the flat, chequered floor below, making its legibility as a three-dimensional volume swim in and out of focus. A dark line down the centre of the picture unexpectedly throws a shadow between the model's legs, revealing itself to be a pole.

Once we realise this, we are suspended between reading it as a compositional element and narratively feeling the menace of a pole placed too close to a cowering woman's face. It is a compelling and slightly maddening painting, emblematic of Uglow's lifelong manipulation of the building blocks of painting in order to both court and defy rationality.

This nonconformism characterises Uglow's relationship to painting. As the Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert exhibition demonstrates, his works strike a fine balance between awkwardness and beauty. Uglow himself gave an apt summation of his own work in 1996: '[Cezanne] helps me to dare to follow my most awkward, foolish passions and obsessions, to wave my own red flags in the dull faces of late-century salon hacks and killers.'

Kate Aspinall, artist, historian and writer

'Euan Uglow' is at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert from 22nd May to 19th July 2024

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation