Named after a combination of the German words for building ('bau') and house ('haus'), the Bauhaus design school was first established in the German town of Weimar in 1919 by Walter Gropius.

In his Manifesto of the Staatliches Bauhaus, Gropius wrote that the school should 'strive for, conceive and create the new building of the future that will unite every discipline, architecture and sculpture and painting'. Taking inspiration from the Arts and Crafts movement and the interdisciplinary concept of Gesamtkunstwerk (loosely translated as a 'total artwork'), the Bauhaus focused on progressive teaching methods in which its students and tutors worked together as a community to achieve its aims.

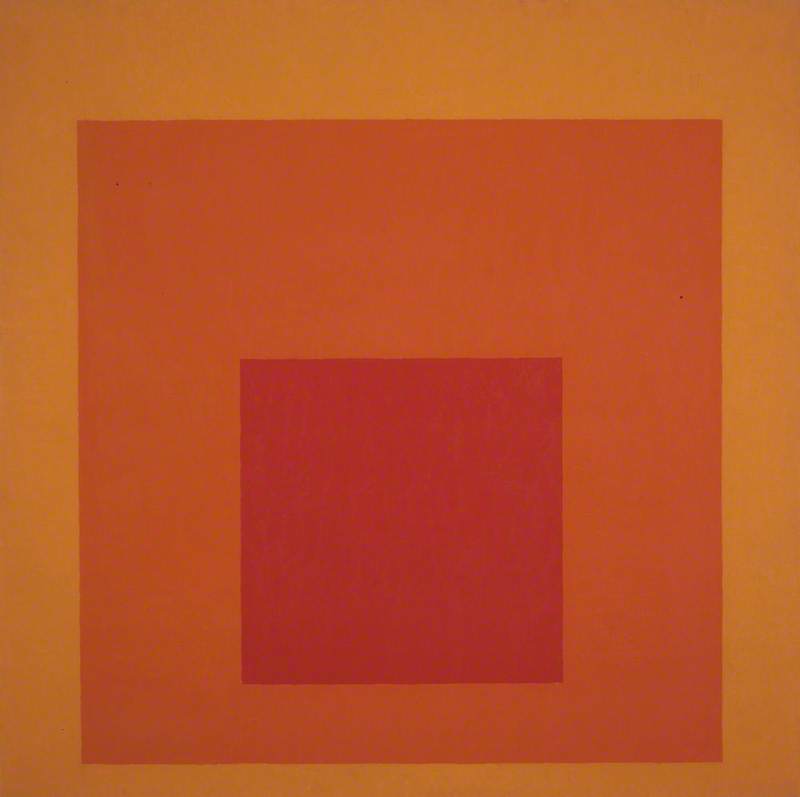

Experimentation was at the heart of the Bauhaus and its radical approach to education. Workshops were created for every discipline, including metal, weaving and carpentry. Gropius hired artistic pioneers such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Paul Klee, Josef Albers and Wassily Kandinsky as masters of the workshops, placing them in charge of fostering the future of the avant-garde. In 1925, the school relocated to the town of Dessau, where it would operate actively for almost a decade. Despite international acclaim and a brief stint as a private institute in Berlin, the Bauhaus was finally forced to close its doors in 1934 by the Nazi authorities.

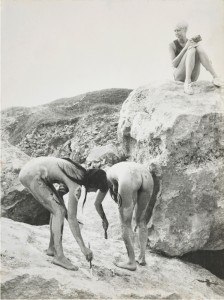

Gropius was the first Bauhäusler to move to London in 1934, with Marcel Breuer (former head of furniture) and László Moholy-Nagy (former head of metalwork) joining him the following year. The school's former director and his old colleagues continued to spread Bauhaus aesthetics in their work for numerous clients, including the design and architecture firm Isokon. It is no surprise that the trio were all residents in Hampstead's Lawn Road flats, Isokon's debut project and Britain's first building to be made of reinforced concrete. The flats were at the centre of a creative community inhabited by the likes of Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, as well as Piet Mondrian and George Orwell.

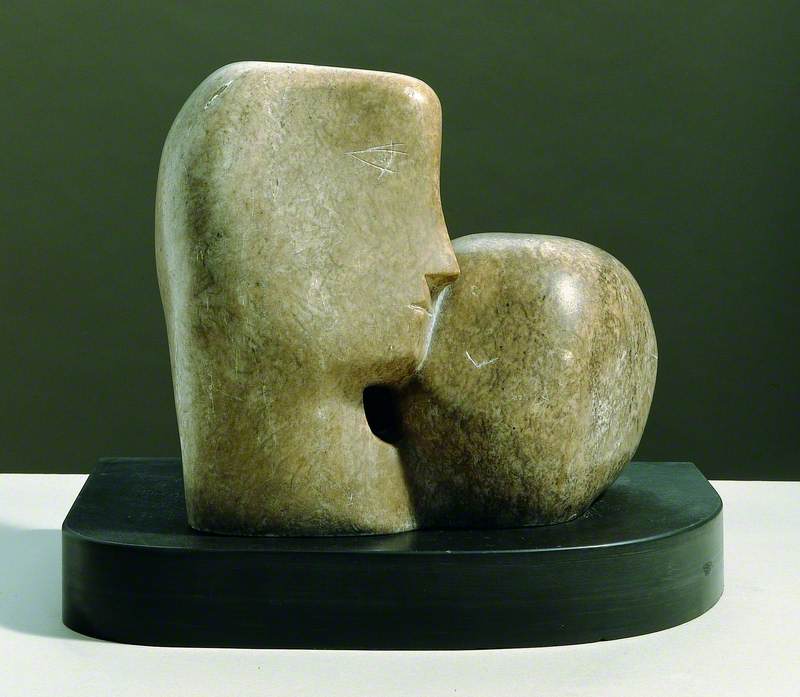

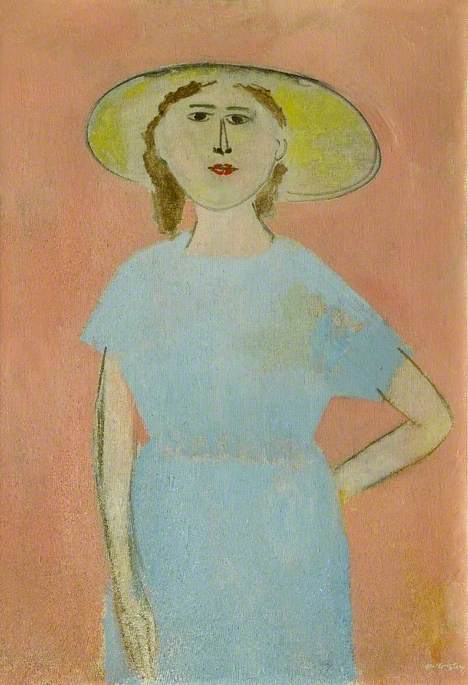

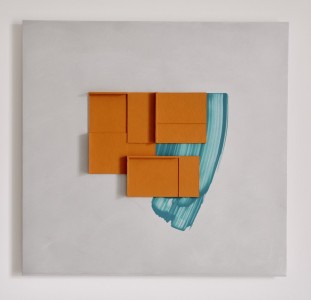

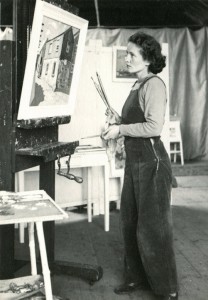

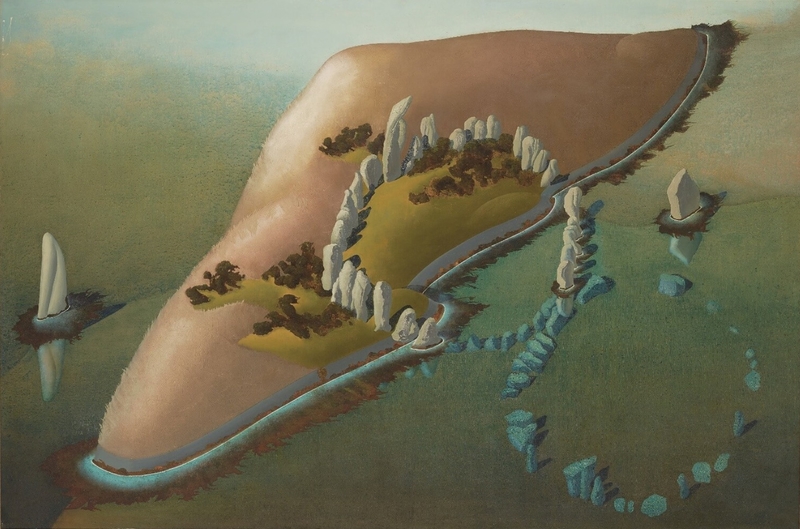

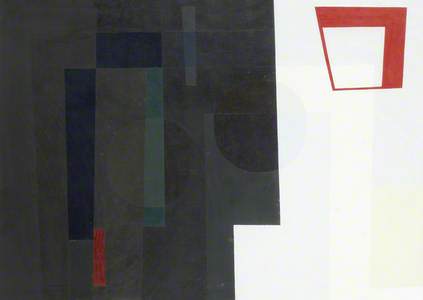

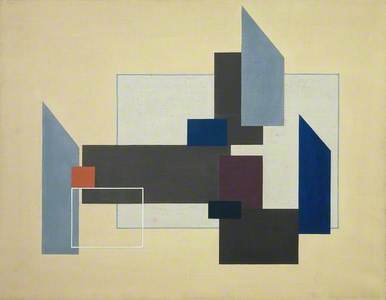

Hepworth and Nicholson had already begun experimenting with abstraction in their respective works during the early 1930s, while their friend Alastair Morton balanced the production of 'constructivist' oil paintings alongside regular collaborations with other artists to create textiles for his company, Edinburgh Weavers. John Cecil Stephenson, a neighbour of Hepworth's and Nicholson's, was also considered to be one of Britain's leading modernist artists at work in the interwar years.

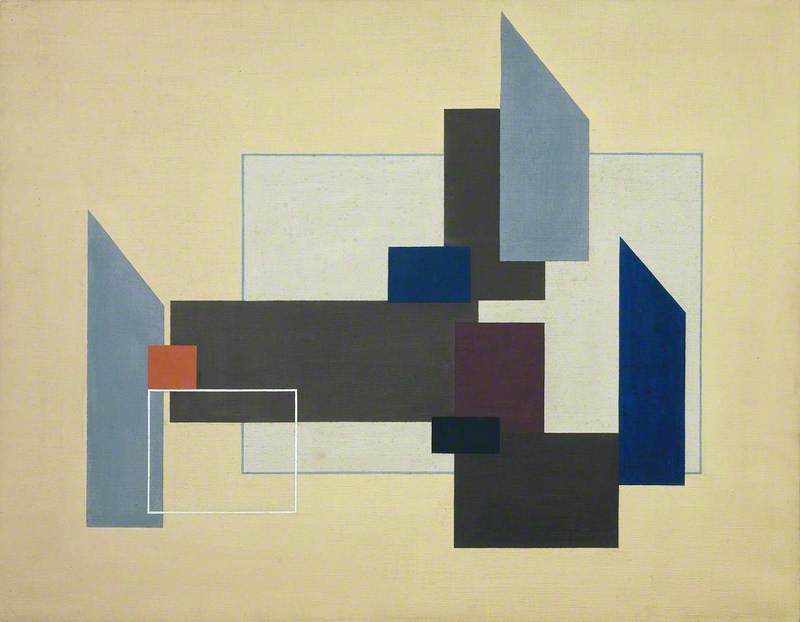

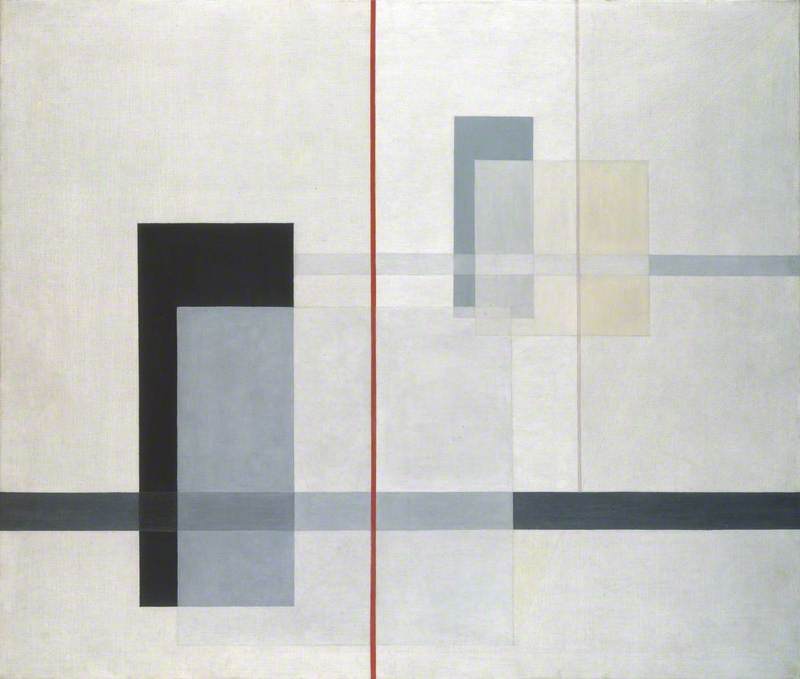

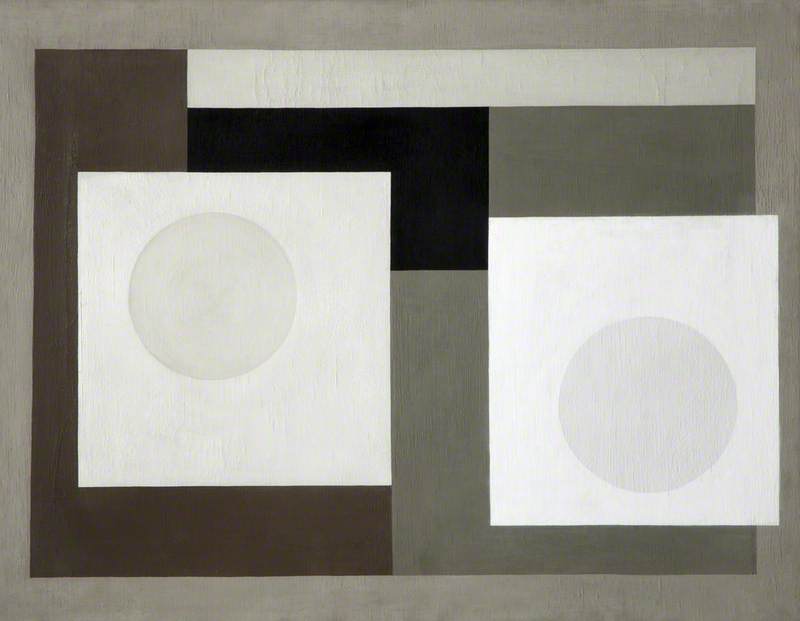

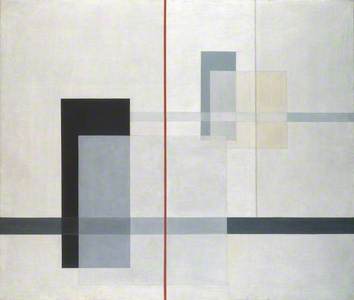

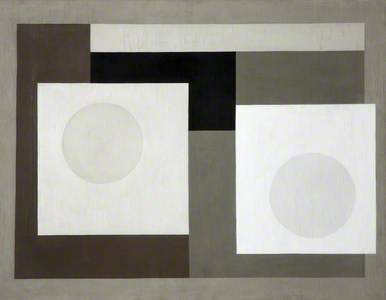

Compositions made up of interlocking lines and forms repeatedly appear in works by all four artists during this period: Nicholson's 1934 (painting), Morton's Dark and Light (1938), Stephenson's Painting (1937) and Hepworth's Conoid, Sphere and Hollow III (1938).

They can all be compared to the geometry and minimal colour palette in Moholy-Nagy's K VII (1922) painted over a decade earlier, alongside Mondrian's philosophy of Neo-Plasticism and his approach to painting.

Building on their earlier involvement with Paul Nash's Unit One group and the influence of the Bauhäuslers, Nicholson worked together with the architect Leslie Martin and sculptor Naum Gabo to produce a series of periodicals uniting architecture with painting and sculpture. Circle: International Survey of Constructivist Art (1937) was the only one to actually be completed and published (the layout being designed by Hepworth), with contributors such as Gropius, Le Corbusier, Herbert Read and Mondrian, but it signalled a synthesis of utopian ideals shared by numerous avant-garde artists living and working in London at the time.

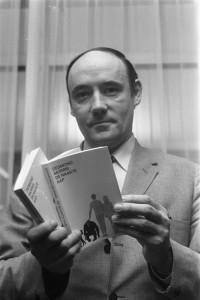

In his book Bauhaus Go West, the historian Alan Powers argues that the Bauhäuslers in Britain 'fitted into the modernist scene here, it was not dependent on them'. Indeed, they were not the only émigrés to be challenging Britain's climate of conservative architecture and design during the 1930s. Berthold Lubetkin, Ernő Goldfinger, Serge Chermayeff, Erich Mendelsohn, and Isokon architect Wells Coates, were all immigrants based in the UK long before the arrival of Gropius, Breuer and Moholy-Nagy. Coates was one of the founding members of the MARS Group (Modern Architecture Research Group) in 1933, a think tank involving architects and critics like Goldfinger, Maxwell Fry, Denys Lasdun and later on Gropius, Breuer, Moholy-Nagy. The possibilities of modernism were never isolated to the Bauhaus and its teachings; the MARS Group saw it as a movement with the potential to transform quotidian living on a national scale.

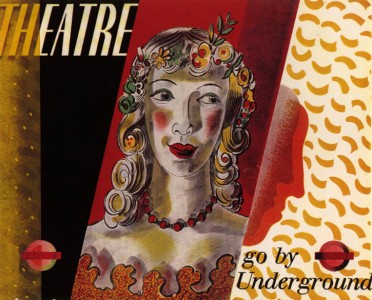

However, not everyone in Britain was as accepting of artists and architects promoting the so-called 'international style' in the UK. In a letter to the architect Oliver Hill, London Transport's first chief executive Frank Pick captured the general sentiment of the British towards the Bauhäuslers: 'Let us leave the continent to pursue their own tricks and go our own way traditionally'. Writing for Dezeen earlier this year, the critic and author Owen Hatherley touches upon the reasons why the Bauhaus was not embraced with open arms by the British establishment: 'There was enormous hostility in Britain to the Bauhaus and what it stood for: abstraction, theory, unashamed modernity and a very alien version of socialism.'

While Moholy-Nagy 'relished the opportunities that London provided', Gropius called Britain a 'land of fog and emotional nightmares'. By 1937, the trio of Bauhäuslers left London in order to take up teaching positions in the United States, with Gropius and Breuer moving to Harvard and Moholy-Nagy establishing the New Bauhaus in Chicago. The legacy of Bauhaus ideals in Britain may not be quite as widespread as Gropius and the former masters had hoped, but it certainly caused a seismic shift in British modernism and laid the foundations for the prevalence of prefabrication in post-war architecture.

Victoria Rodrigues O'Donnell, Museum Assistant at the Fashion and Textile Museum and freelance writer