It is a truth universally acknowledged that everyone is in possession of a bottom. It's something that unites us, be we human, deity or even merperson! But being behind us, bums often miss out on the limelight. While artists might focus on faces, forearms or flowing robes, art history is nevertheless full of nude figures and bottoms in particular – especially in Renaissance art, which paid a lot of attention to the male buttocks. By shifting our gaze and getting to the bottom of things, we can see that artists depict backsides for a range of reasons.

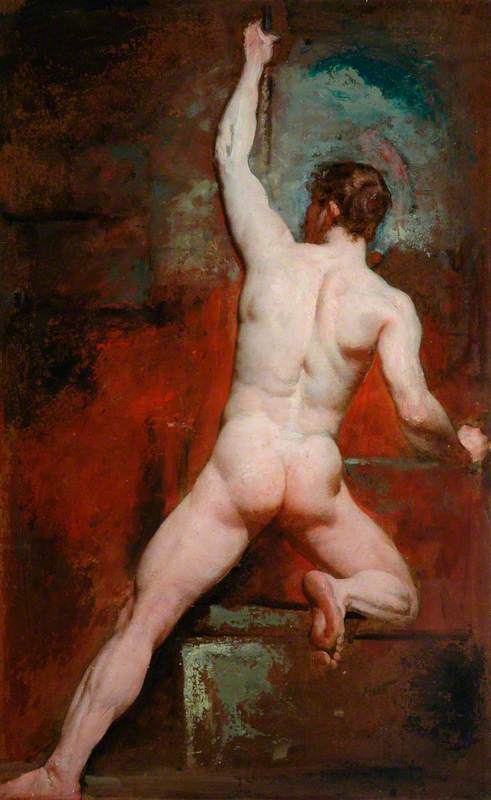

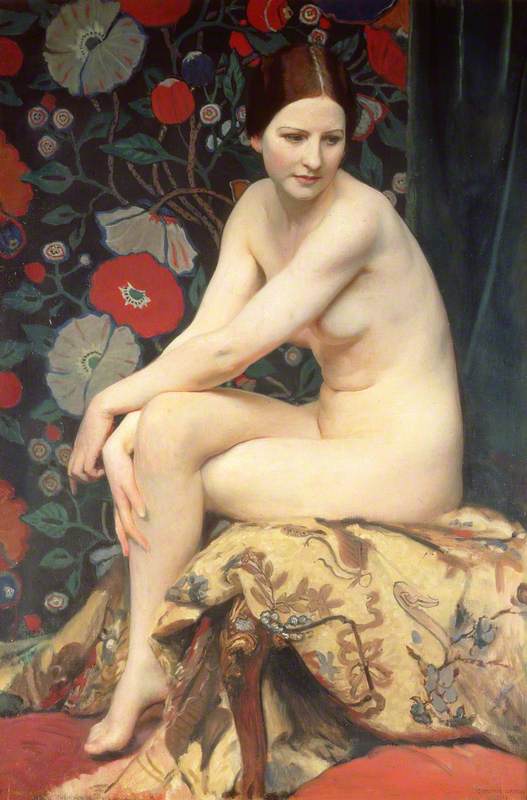

An artist may be revealing to the world that they've mastered how to portray glutes – a notoriously tricky muscle group to get right; or they may be offering the viewer something just cheeky enough to enjoy, or they might be trying to emphasise qualities such as heroism, purity or beauty. As a result, many artistic depictions present an ideal rather than a reality, with bodies perfectly proportioned – think of all those gods and goddesses – or erotically charged. This is particularly the case with images of women seen through a male gaze.

Museum Bums: A Cheeky Look at Butts in Art

Mark Small and Jack Shoulder (2023)

Bums can be found in artworks in museums all across the world, and the co-authors of Museum Bums: A Cheeky Look at Butts in Art and co-curators of @MuseumBums have been scouring the Art UK collections to find some of the most thought-provoking pre-nineteenth century posteriors on offer.

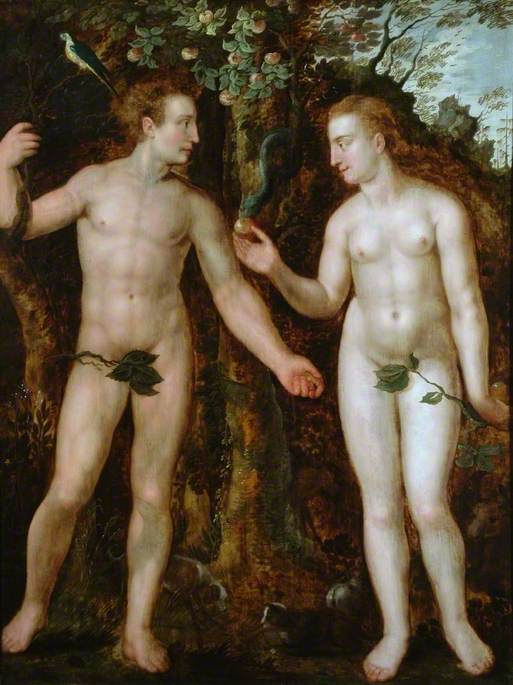

The Temptation of Adam and Eve

The Temptation of Adam and Eve

Girolamo Macchietti (1535–1592) (studio of)

In the beginning was the word and the word was… 'Testing? Testing..? 1,2,3.' The Garden of Eden is always a popular subject for artists, offering a chance to portray lush greenery and the naked form in ecclesiastical spaces with impunity. Adam and Eve's nakedness can't be sinful; sin hadn't been unleashed yet. Girolamo Macchietti's Adam and Eve have a symmetry that in fact suggests their conflicting views on the temptation offered by the curly haired serpent; Adam, his bottom just visible, looks like he's preparing to run away, while Eve is weighing up the opportunity to take a bite of the forbidden fruit.

The Judgement of Paris

Who would have thought that gifting an apple 'to the fairest' would cause so much trouble? Eris, the goddess of discord, that's who! After disrupting the wedding of Peleus and Thetis because she wasn't invited, Eris threw a golden apple to all the goddesses at the feast. Zeus, chief of the gods, turned to Paris to judge which goddess was the most beautiful and should receive the apple; Hera, Athena or Aphrodite (their Roman counterparts were Juno, Minerva and Venus).

Each goddess offered Paris a bribe, which he carefully weighed before awarding the prize to Aphrodite, goddess of love – she had irresistibly promised him Helen of Troy. Really, he should have given it to the bride. It was her special day after all.

This episode, known as the Judgement of Paris, has offered the chance for many other artists – including Rubens, François Boucher and James Thornhill – to depict several bums. In Rubens' famous depiction, the female form in varying states of undress is the focus; as Athena faces us, hers is the only bottom not visible.

The Triumph of Galatea

We can practically smell the salty tang of the sea foam in this piece. The sea-nymph Galatea's flowing cloak echoes the crashing waves as her attendants carry her aloft.

Although the light in the painting suggests Galatea is our focus, there is some reflected glow on her court. The central figure, just below Galatea, draws the eye. She's a sea-being, with fin-like wings and a fish tail, but also… a bum, proving not for the last time, that merfolk do have bums!

The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus')

One of the most famous bottoms of all time. Diego Velázquez's Venus (one of the artist's only surviving female nudes) exists in a hazy, dreamlike state as she lounges languorously on her chaise-longue. She's reflected in her mirror – she's watching you looking at her.

The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus')

1647-51

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

The Rokeby Venus is one of the rare 400-odd-year-old paintings which can claim a significant Wikipedia page update in the last few years! No stranger to acts of destruction, the painting was recently the subject of a protest in 2023 by the climate activist group Just Stop Oil, whose aims include highlighting the problematic relationship between the art world and fossil fuels. The protest echoed activism around the painting more than a century earlier when Suffragette Mary Richardson attacked the painting with a butcher's knife.

We recently celebrated The Rokeby Venus in a bespoke Museum Bums tour, while she was on loan to the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool as part of the National Gallery's 200th anniversary celebrations.

Museum Bums talk in front of the Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez

Walker Art Gallery Liverpool, 2024

Shiva Nataraja

Shiva is the central god in the Hindu tradition, often represented in art as a multi-limbed figure. Here he is shown performing the Dance of Creation, in an image which encompasses his dominion over destruction, creation and the never-ending cycle of time.

This Hindu deity is situated within a halo of fire: in his upper-right hand he holds a small drum symbolising creation; with his lower-right hand he makes abhayamudra, the gesture that allays fear. With his front-left hand pointing to his raised left foot, Shiva indicates his offer of refuge to lost souls. Seen from behind, the pose of the dance accentuates the curve of his thigh and bottom.

The symbols and movements in this piece tell us that this Shiva will guide and protect those who follow him.

Orpheus Enchanting the Animals

As the browns, buffs and beiges of the various beasts' fur blend into the background, and Orpheus' musical instrument is obscured, this work – now thought to be by Titian – instead draws our full attention to the mythological musician.

Orpheus Enchanting the Animals

1560s

Padovanino (1588–1649) (attributed to) and Titian (c.1488–1576) (workshop of)

Here he is in all his glowy glory, proving his elite musicality by charming the socks off the animals – even the unicorn is impressed! Orpheus is a queer icon in some circles – having looked back and doomed his wife Eurydice to the underworld, he swore that he would never love another woman. He kept this promise, but that didn't stop him from romancing men; Orpheus turned his attention to the men of Thrace, and according to the legend, invented homosexuality (in Thrace at least).

Mercury Rising

Up, up and away! Mercury's winged feet and hand held aloft signal that the messenger god is about to take flight, presumably to deliver some important news or, more likely, to make some mischief. Although this work is a modern copy of Giambologna's Mercury from the sixteenth century – of which there are many copies, including one in the National Museum Wales (shown below) – the fleet-footed flyer is a fitting fixture for Colchester's Balkerne Gate, the largest surviving Roman gateway in Britain.

The Gateway once linked the important cities of Londinium and Camulodunum so it makes sense that a mythological messenger would grace this site, sharing the vital goings on from near and far. Both the Gate and its later artistic addition tell an important story about the impact and legacy of Rome, which is still very much with us today.

Still life with Peaches, Red Grapes and a Walnut

Still life with Peaches, Red Grapes and a Walnut

late 17th C

Ernst Stuven (1657–1712)

Peaches have signified bums in artworks for centuries, maybe even millennia. There are even frescoes of peaches at Herculaneum, which were buried under volcanic ash after Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD. More recently, a peach played a pivotal role in the book and then film Call Me By Your Name, which catapulted Timothée Chalamet to stardom, and the peach emoji from your phone was featured in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2010. There's no escaping them. It's often said that the viewer completes an artwork, and that means that when we're looking at pictures of peaches, they're definitely bums.

Our book features a chapter entitled 'When is a Bum not a Bum?' and this explores those objects in museums and galleries which aren't bums, but definitely are if you look hard enough. Peaches, abstract Henry Moore sculptures (see above), Tom Daley's olympic-medal-winning Speedos from the 2012 Olympics (they're at the Museum of London), and chairs with suspiciously luscious seats carved into them – they all bring to mind bums, even in a gallery completely devoid of nudes.

Allegory of the Arts and Sciences with a Portrait of Jan Govertsen van der Aer

Art and Science might sound like a Thursday afternoon at school, but Isaac Seeman's Allegory (which is a copy after an original by Cornelisz. van Haarlem, who it's been said had a penchant for male backsides) gives us personifications of these subjects, who are engaged in a lively discussion at a bustling symposium-like space. We wonder who's winning the conversation.

We know that with Peace seated to the left of the scene, the debate will be spirited and in good faith, while the figure on the right, whose bum is exposed, is inspiring the men to consider the human form. This type of painting was often commissioned to show that the sitter – in this case, Jan Govertsz. van der Aar (1544/1545–1612), a merchant from Leyden – had impeccable taste and was the height of sophistication.

Hermaphrodite

Artists like to show off their skills – they are, after all, experts and masters of their craft. The figure of Hermaphrodite – in classical mythology, Hermaphroditus was the son of Hermes and Aphrodite who blended forms with the nymph Salmacis – offers artists a way to surprise and delight viewers. This sleeping hermaphrodite (a larger marble version from antiquity is in the collection of the Villa Borghese, Rome) appears to lie on a comfy, cushiony mattress that is almost impossible to believe isn't full of feathers, as well as a figure that shifts from masculine to feminine as you make your way around the work.

The Sleeping (Borghese) Hermaphrodite

c.1765

Louis Gabriel Blanchet (1705–1772)

Hermaphrodite reminds us that bodies beyond and in between the binary of masculine and feminine have been around for centuries, are deserving of their place in our museums and galleries, and have their own unique beauty.

Once you start seeking bums in art, you see them everywhere! Background characters now spring to life and still-life peaches take on a callipygian aspect.

Mark Small and Jack Shoulder, co-authors of Museum Bums: A Cheeky Look at Butts in Art

If you're keen to explore more bums throughout art history, you can purchase a copy of Museum Bums: A Cheeky Look at Butts in Art from your favourite bookshop or museum gift shop – as well as the Art UK Shop. A 2025 calendar is also available and greetings cards to send Museum Bums to your friends

For a daily dose of art history that's peachy-keen, follow @MuseumBums on X and Instagram

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation