John Henry Lorimer (1856–1936), born in Edinburgh and resident of Fife, London and Paris, was known to have a 'quiet style' and 'conservative approach to painting' when he was active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. His work was popular, and he experienced a meteoric rise in success at an early age. Why then does he barely receive a mention in art history books?

Janet Alice Lorimer and Child

1890

John Henry Lorimer (1856–1936)

An exceptional portrait of Janet Alice Lorimer, John Henry's sister, illustrates his skill as a painter. Janet is seated, and gazes down at her boy who is perched on a table by her side. She is wearing a satin and chiffon cream gown; her hair is swept up and softly frames her face. She is pictured as a society Lady, with a subdued simple necklace of pearls and light chain bracelet. Her loving devotion to her son is evident in the gentle reassuring way she holds his small hand.

This is a sensitive portrayal that blends the English tradition of using portraiture to emphasise status and style with the Scots preference for informality. In these terms, it could be said to be a truly British portrait. It was painted at Kellie Castle, while Janet and her children were visiting for the summer of 1890 and was exhibited that same year at the New Gallery in London. Three years later it featured in the Royal Scottish Academy show.

John Henry considered himself a British painter and the portrait is a perfect illustration of his style, which was largely influenced by Realist painters like John Everett Millais, society portraitists such as the American John Singer Sargent, and his Scottish teachers George Paul Chalmers and William McTaggart.

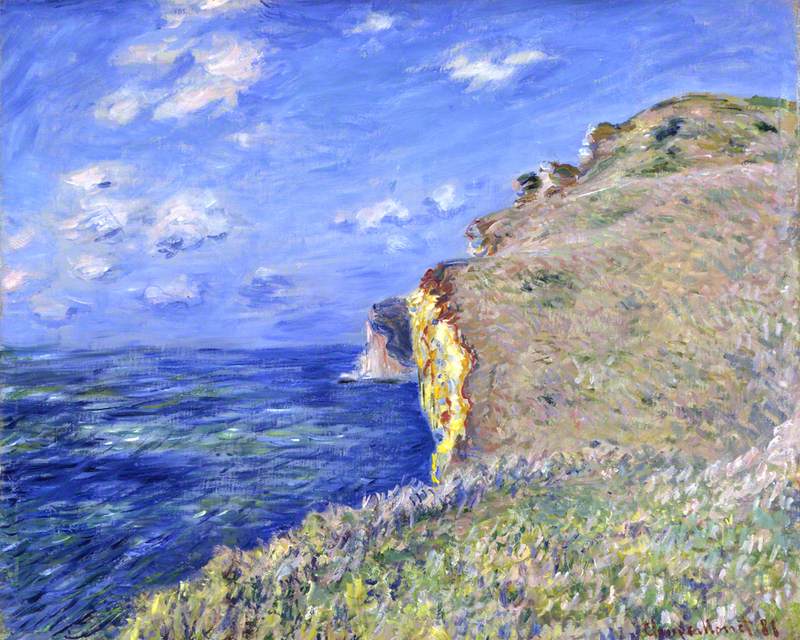

John Henry's preference was not to draw attention to the paint and overwork the surface of the canvas – as the avant-garde French Impressionists were doing – but rather to focus on a more subtle handling of paint to create a beautiful picture that did not mimic reality but augmented it. He created a subjective realism rather than an objective study. Yet his 1890 portrait of Janet begins to feel positively old-fashioned when compared to Woman Seated on a Bench, painted nearly 20 years earlier by Claude Monet.

Although not at the cutting edge of painting development, John Henry was both well-regarded and successful in his own time. His paintings were exhibited at the Royal Academy and Paris Salon, often appearing 'on the line' – a placement reserved for a select few canvases considered 'worthy' of being appreciated at eye level. In 1900, his tragic scene of a weeping bride, The Eleventh Hour (c.1894, private collection) – set in a south-facing room at Kellie – was awarded a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris.

James Lorimer (1818–1890), Jurist and Political Philosopher

1890

John Henry Lorimer (1856–1936)

Despite all this fame and exposure, if you flick through books on Scottish art history, John Henry barely gets a mention. These texts have tended to focus on the cause and effect of changing styles, which has manufactured an efficient timeline that suggests one thing leads inevitably to another. Lorimer's work has been overlooked because it was not avant-garde and did not have much of an effect on new and emerging styles. He drew on more traditional aspects of painting that were already tried and tested. Yet, as Charlotte Lorimer (co-curator of the Lorimer Society's recent Edinburgh City Art Centre exhibition, 'Reflections: The light and life of John Henry Lorimer') has noted:

'While artists such as Claude Monet and Edgar Degas pushed the boundaries of painting and were rejected by traditional galleries and the Paris Salon, Lorimer developed a more classical style and won medals from the Salon and praise from critics. History tends to remember the rebels. But there's also a place for the quiet craftsmanship of artists such as Lorimer.'

In Duncan Macmillan's seminal Scottish Art, 1460–2000, John Henry is mentioned briefly in a chapter focusing on those Scots influenced by the rural scenes of the elderly Gustave Courbet, rather than in the following section, titled: 'The 1890s: the opening of the Modern Era'. Macmillan admits John Henry was 'rather a chameleon figure, a reluctant but successful portrait painter who… modelled himself very much on Millais' and had 'Pre-Raphaelite leanings'.

By comparing Lorimer's work with that of his contemporaries, you would be forgiven for thinking that he was much older than his years.

As Macmillan has suggested, Lorimer's skill for capturing luminous light came from painters who chose to look back in history for inspiration, such as the Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt (who was 29 years older than Lorimer), rather than forward into uncharted territory.

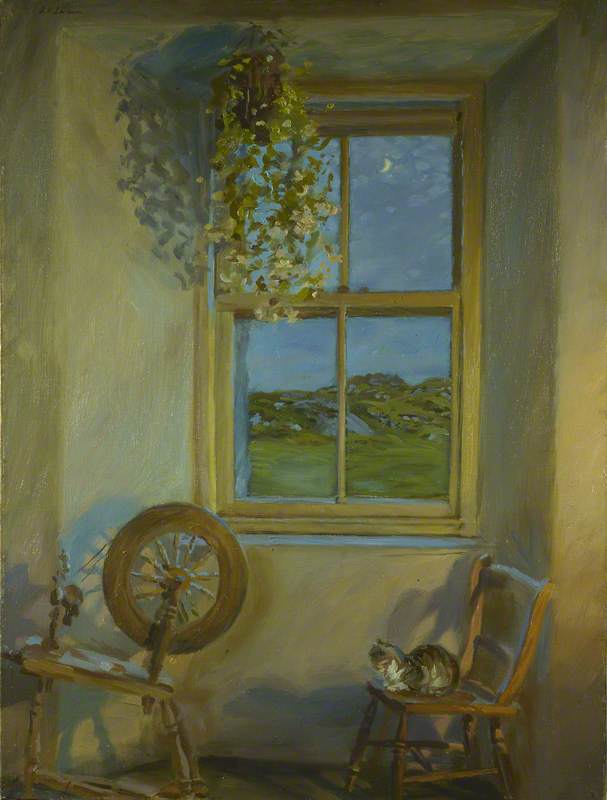

William McTaggart was Lorimer's tutor at Edinburgh School of Art and his painting of a boat bobbing on the sea has an impressionistic brushstroke that feels more modern than Lorimer's quiet interior. This is not to suggest that Lorimer's exacting study of luminous light at the gloaming is not an accomplished painting, but rather to note that the subject matter – safe inside looking out to the fresh air of Iona – as well as the gentle style, demonstrates a cautious student. McTaggart finished his painting nearly 40 years before Lorimer completed Interior, Iona.

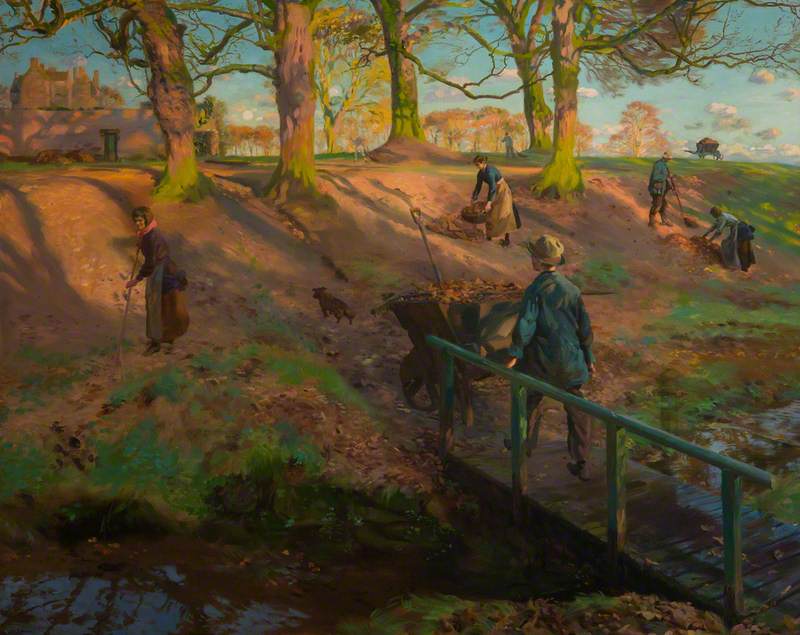

Lorimer painted The Long Shadows 35 years after Guthrie's Hard at It. Both focus on labour in a bucolic setting, yet, despite the obvious skill in capturing the rosy sunset, Lorimer's brushwork could be mistaken for an earlier period. While Guthrie's paint is applied with wide smudges and bold strokes in a wild gestural manner, John Henry's brush marks are barely visible.

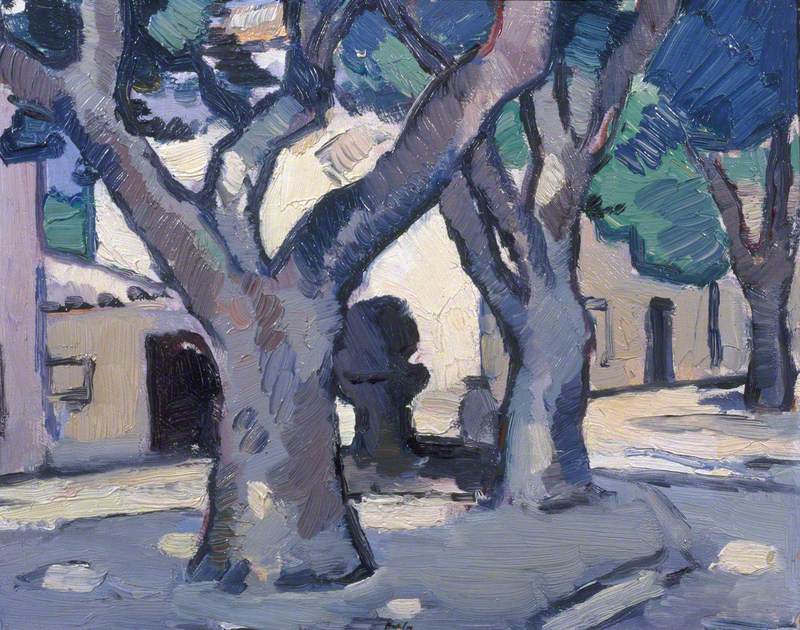

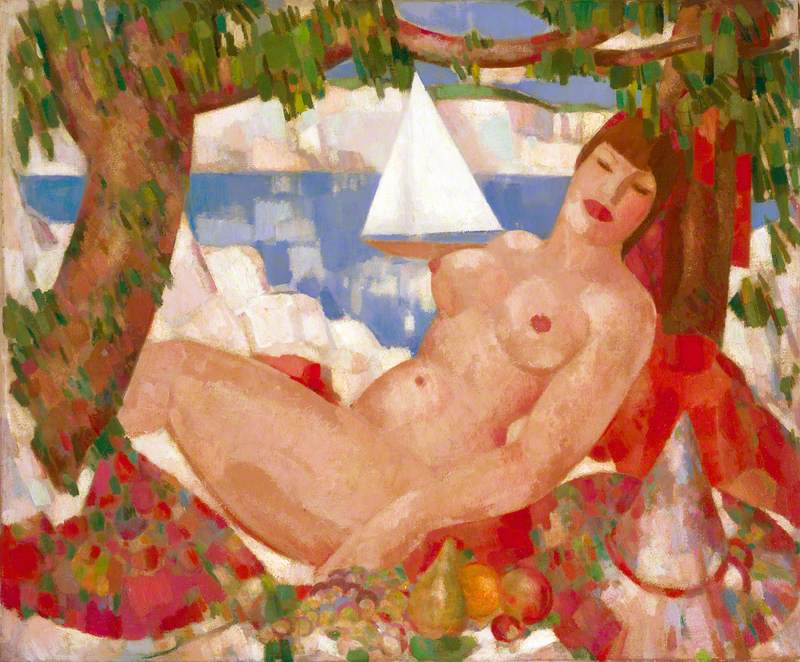

Game of Tennis, Luxembourg Gardens

c.1906

Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935)

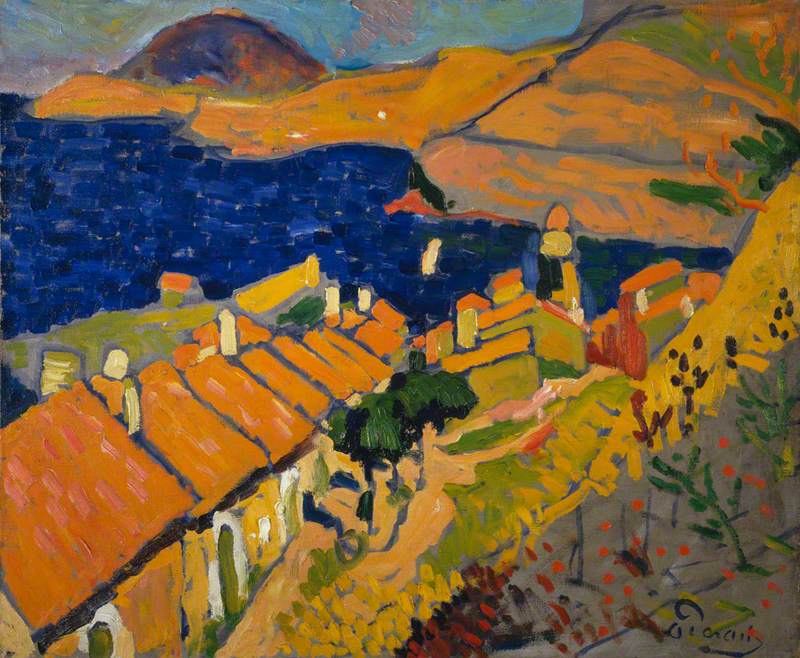

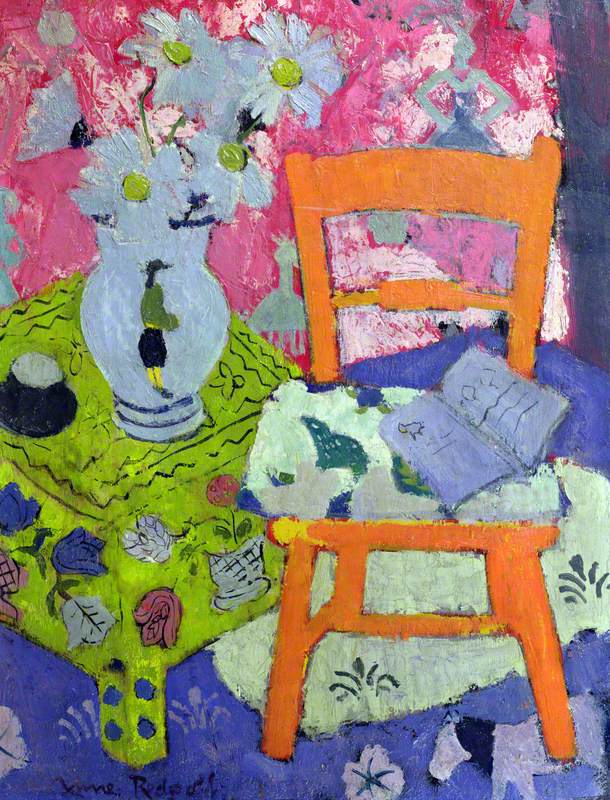

Peploe painted Game of Tennis and Lorimer The Flight of the Swallows in the same year, yet the styles on show are starkly different. Peploe's gestural style strides forward into abstraction, clearly influenced by the post-impressionistic 'wild beast' canvases of French Fauvist painters such as Henri Matisse and André Derain. Meanwhile, Lorimer seemingly languishes in an old-fashioned sentimental genre scene.

The Flight of the Swallows

1906

John Henry Lorimer (1856–1936)

You could argue Lorimer was catering to the market as these interiors were hugely popular. Immediately after Flight of the Swallows was exhibited at the Scottish Academy, it was purchased by the newly founded Scottish Modern Arts Association for £100. It was one of their first acquisitions, as part of an ambition to build a national collection that would represent the best of contemporary Scottish art. Yet, Lorimer's work was an exemplar of established tradition, not an example of the experimenting artist.

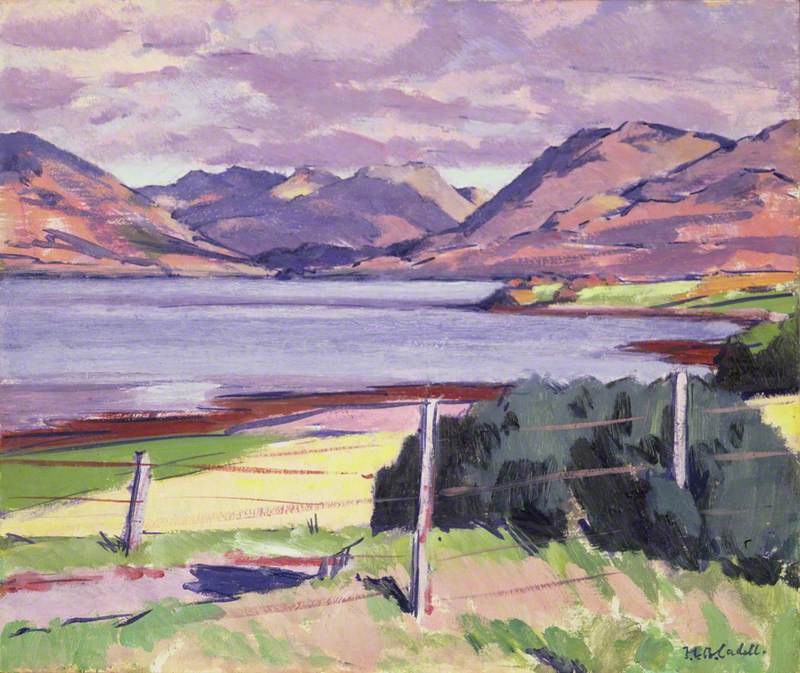

John Duncan Fergusson and Lorimer were both painting in Edinburgh in the 1890s and had travelled to France as part of their training. Fergusson's paintings explored the new styles of Symbolism and Cubism, and were exhibited in the reactionary 1907 Salon D'Automne, while Lorimer exhibited at the official Paris Salon. Established society painters saw the skill in Lorimer's ability to capture tonal variation and light – something most evident in a painting like Sunlight in the South Room.

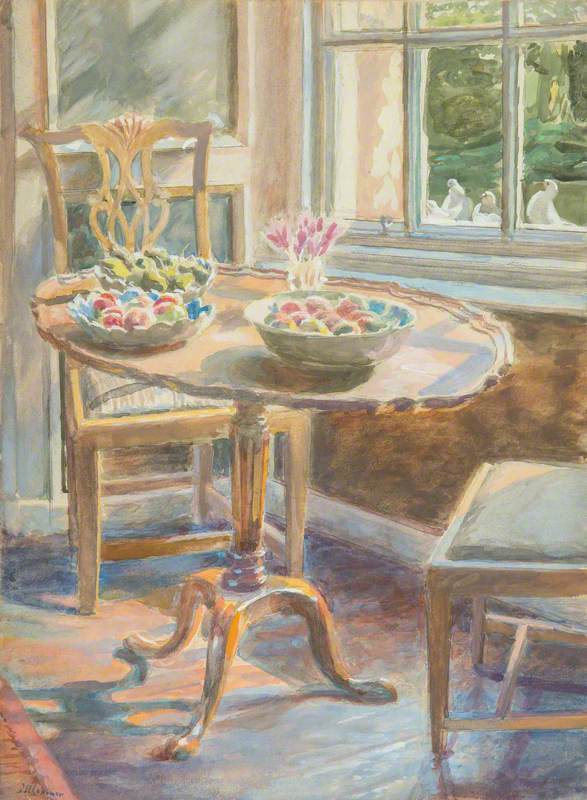

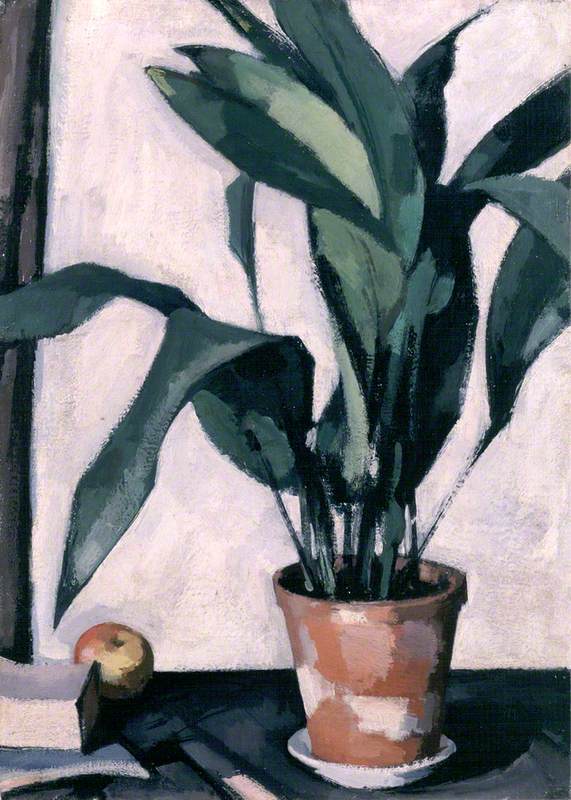

Sunlight in the South Room, Kellie

c.1913

John Henry Lorimer (1856–1936)

Painted four years after Fergusson's Woman on a Balcony, it is a clear demonstration of John Henry's preference for painting's traditional role of replicating the real world.

The watercolours of Lorimer's Scottish contemporary, Arthur Melville, illustrate just how conventional John Henry's work was for this era. In Melville's scene, of a bullfight in Spain, he heightens the frenzy of the crowd by pairing the busy blots of colour with an empty light wash. The flecks of turquoise blue, which punctuate the dense areas, form the 'ring' that confines and intensifies the claustrophobia of the crowd. Melville's style of painting is designed to pulsate with movement. Comparatively, Lorimer's use of watercolour is tame. He does not use colour to create movement or symbolic emotion, but more to illuminate the stillness of a moment and the beauty of an interior space.

John Henry Lorimer was born too late. His style had already been articulated by artists 20 or 30 years his senior such as Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais and George Paul Chalmers, and it had been overtaken by contemporaries like Samuel Peploe and Arthur Melville. This explains, but does not excuse, the disregard for quieter painters like Lorimer, whose styles often hold as much value for understanding the complexity of a cultural moment as the wilder methods of contemporaneous avant-garde painters. They who shout the loudest may capture the attention, but they cannot possibly know the whole story.

You can see John Henry's paintings in the place he loved to paint – Kellie Castle – which is open in April 2022. Check the National Trust for Scotland's website for details.

Antonia Laurence Allen, Regional Curator Edinburgh and East, National Trust for Scotland