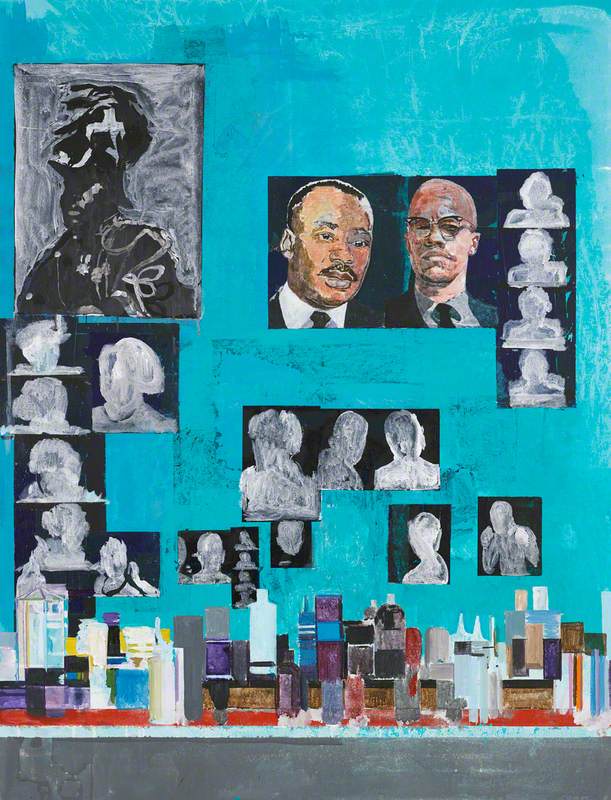

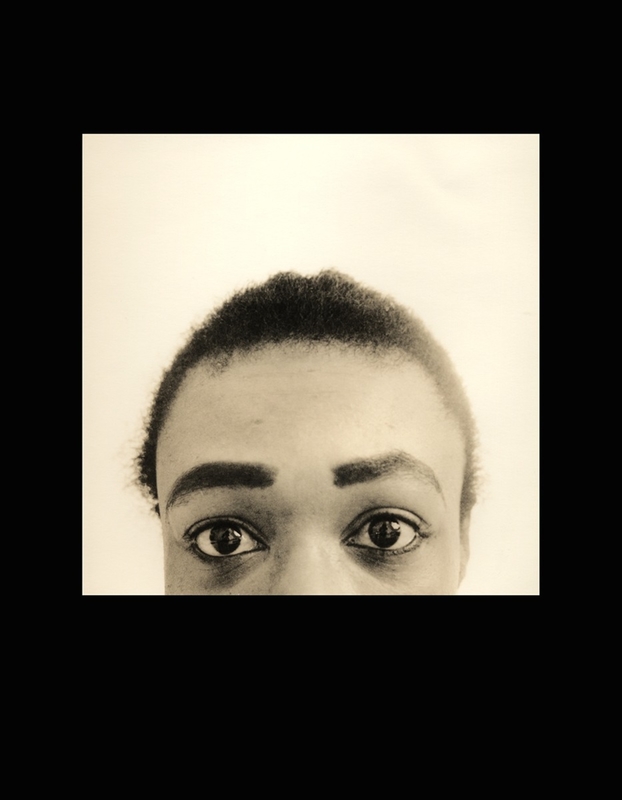

I created the Instagram account @ablackhistoryofart in February of this year, halfway through my Bachelor's in History of Art, out of a frustration at the lack of black figures being discussed in my degree.

The account acts as a means for me to self-educate by researching aspects of art history and visual culture that involve people who are black, and to share it with a growing audience.

View this post on Instagram

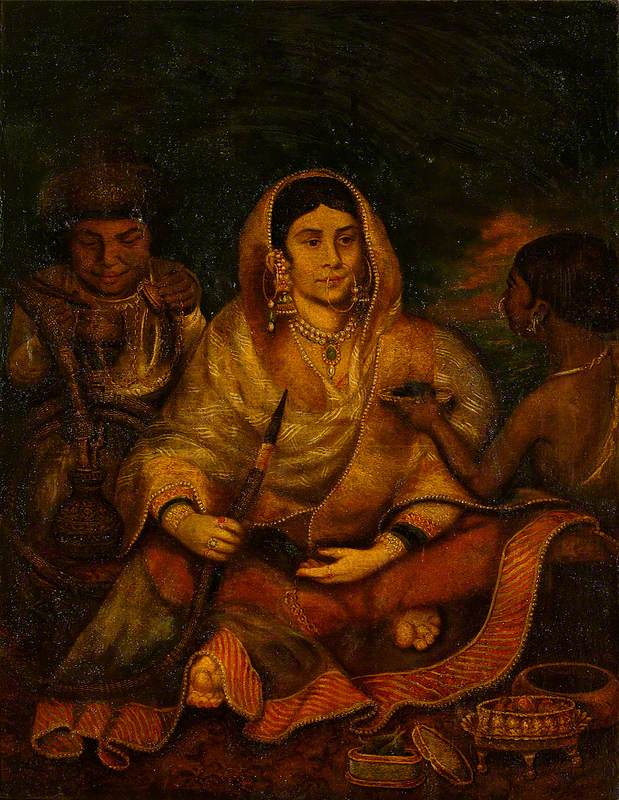

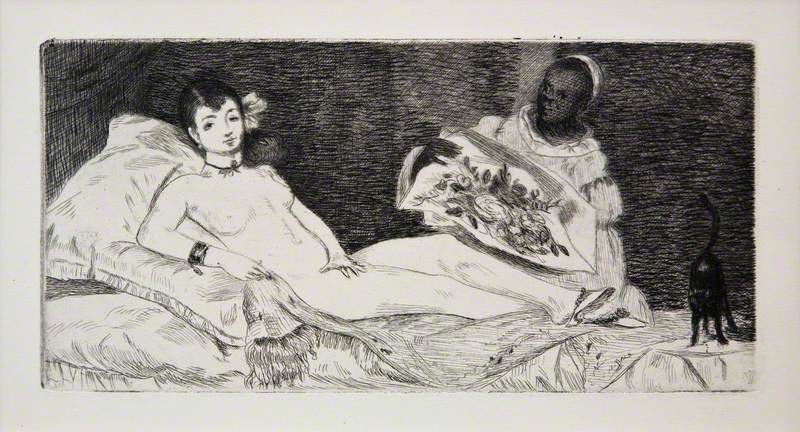

On @ablackhistoryofart, I highlight black artists, sitters, curators and thinkers who have been largely overlooked in the field of art history. The black figures in traditional European paintings are typically in subordinate roles, as servants or enslaved people and there is often little, or nothing known about their identities beyond their relation to a white figure – they are labelled as 'anonymous'.

Here, in a bid to give an identity back to the black figures who have been repeatedly under-recorded, I will discuss the lives of six black sitters in paintings from public UK art collections.

Editorial note: Art UK is actively working with public collections to change and contextualise problematic and racist words used in artwork titles.

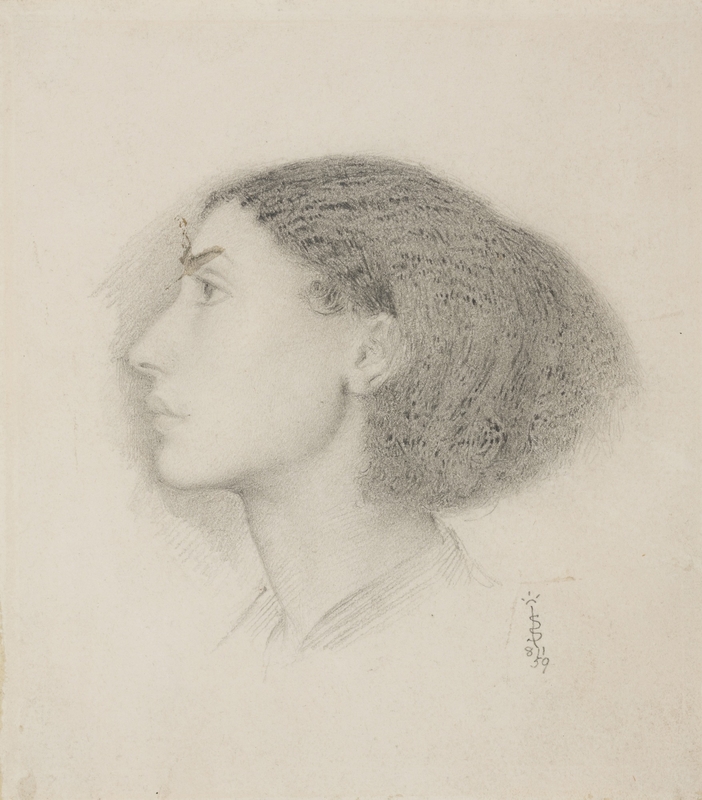

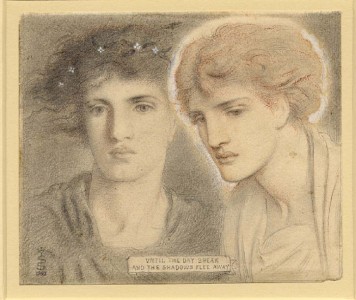

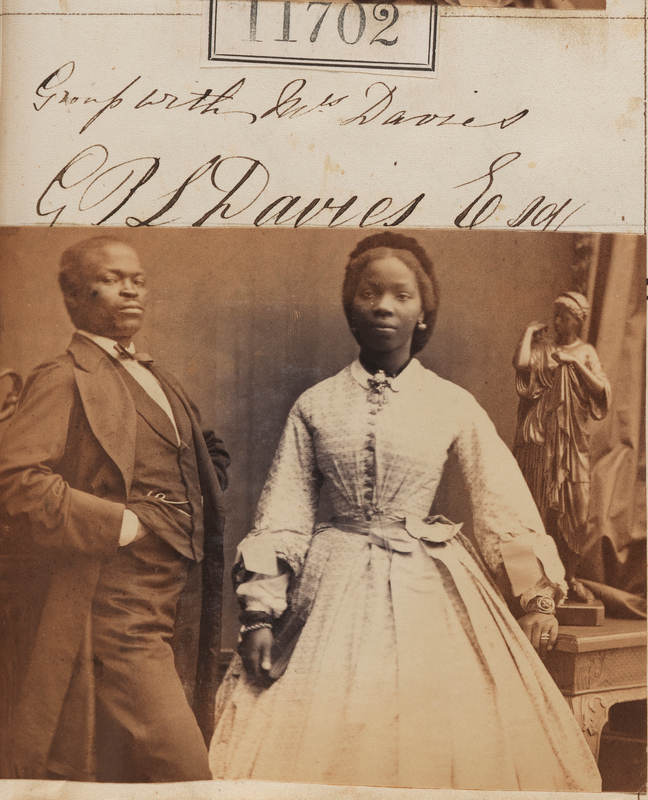

Fanny Eaton

Fanny Eaton was a muse to multiple Pre-Raphaelite artists, including Simeon Solomon, Joanna Boyce Wells and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Last year Art UK published the story 'Fanny Eaton: Jamaican Pre-Raphaelite muse'.

She was born in Jamaica in 1835, as Fanny Antwistle, to a formerly enslaved woman, Matilda Foster, and presumably a British man, although there are no records pertaining to the identity of her father, which suggests that she was born illegitimately.

Fanny Eaton and her mother likely emigrated to England from Jamaica in the 1840s, and the 1851 UK census reveals that her mother, aged 37, was working as a laundress, and Fanny Eaton, aged 16, was working as a servant in London. By the 1860s, Fanny Eaton was living in St Pancras with her husband, James Eaton, the ethnicity of whom is unknown, and was working as a charwoman, as indicated by the 1861 UK census. At the same time, in the years 1859–1867, Eaton found intermittent employment as an artist's model.

The research of Dr Roberto C. Ferrari in 2013 has revealed that Eaton was a paid model at the Royal Academy, with the evidence in receipts that show a Mrs Eaton was paid to model there during dates around 1860. The earliest known studies of Eaton are Simeon Solomon's portraits Mrs Fanny Eaton (1859) and Mrs Fanny Eaton (Profile Left) at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, which were drawn in preparation for the painting The Mother of Moses (1860) at the Delaware Art Museum.

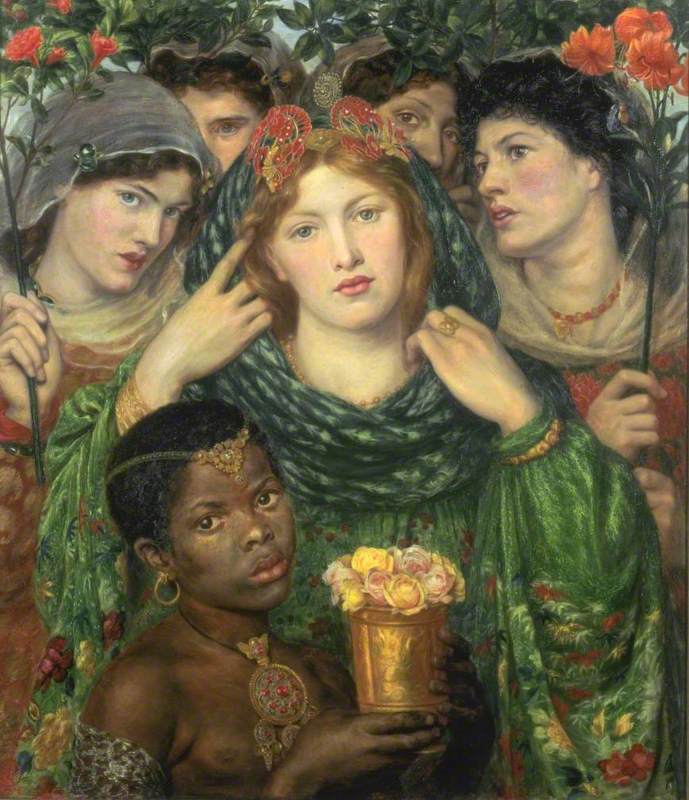

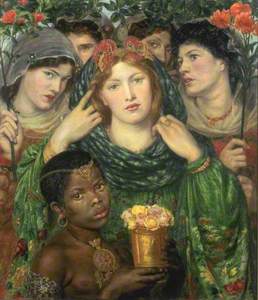

The Pre-Raphelites, based on their perception of her as 'ethnically ambiguous', portrayed Eaton as a range of ethnicities. For instance, in Rossetti's The Beloved (1865–1866) the top half of Eaton's face can be seen behind the pale bride (an attempt at chiaroscuro to enhance the pale skin of the protagonist central figure), and is supposed to appear as 'an Indian or Asian' (said the artist, as quoted in the book Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti) despite the knowledge of her mixed black and white ethnicity.

The young boy in The Beloved

The figure in the bottom left of The Beloved is a young boy whom Rossetti came across while travelling with his employer. He had already completed a study of a girl of mixed black and white ethnicity to use for the figure but opted for the boy, writing 'I mean the colour of my picture to be like jewels, and the jet would be invaluable.'

In likening the complexion of the figure to the colour jet (the glossy black semi-precious stone), Rossetti's words highlight the extreme objectification of black sitters in this period of art history. Figures with darker complexions were fetishised for their 'exotic features'. In this instance, the boy is overtly exoticised and used as an aesthetic device, enhanced by the gold jewellery but also the flowerpot, which was most likely a means to emphasise the pale skin of the bride.

As William E. Fredeman highlights in The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (2005), the artist also mentioned that the boy cried while posing, but he noted only the aesthetic quality of this as it made his skin look darker and glossier. This reveals that the drawing was made against the boy's will, and feeds into the larger narrative in art history of the exploitation of black figures, which, in this case, involved a child.

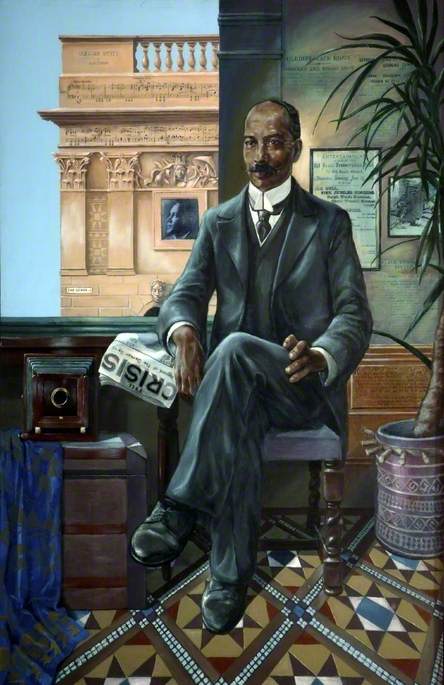

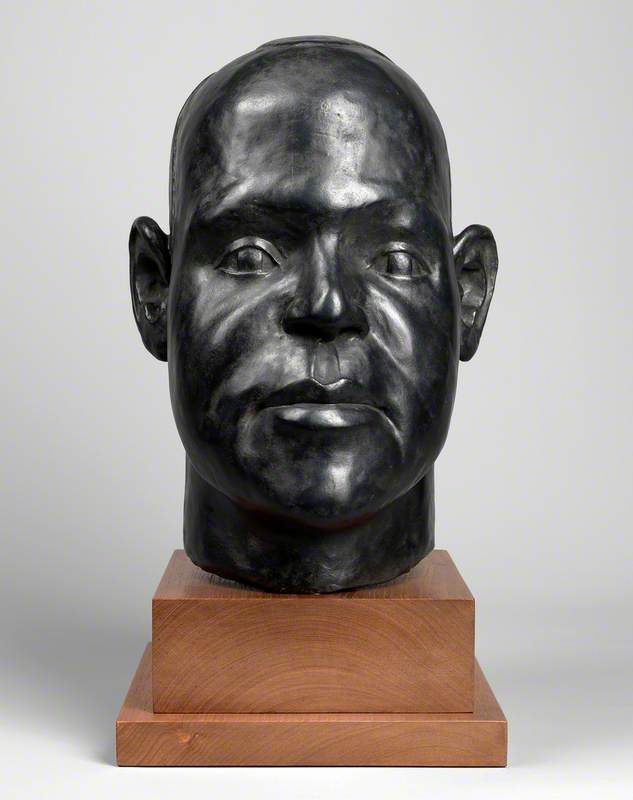

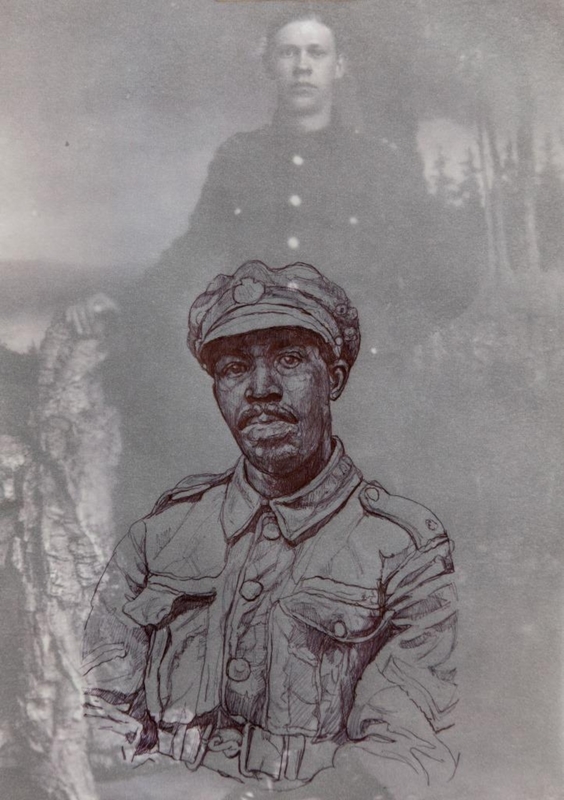

Louis Black

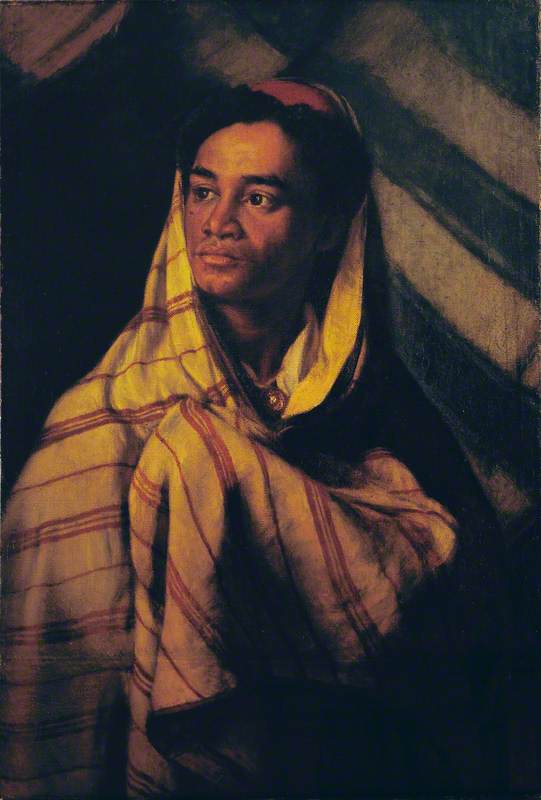

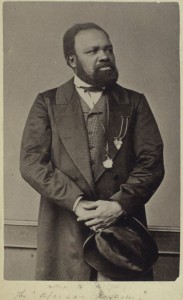

Louis Black was an enslaved Afro-Brazilian man born around 1820, who came to Montrose, Scotland in the 1830s with his employer, Alexander McKay.

Having attended school in Montrose, he made the decision to remain in Scotland where he was free, and MacKay returned to Brazil, and left an annuity to Black in his will. He worked in Montrose as a gardener and a waiter in the area and was also known to be a keen golfer. The painting Louis Black was created by a local artist when the sitter was middle-aged, although the exact date the painting was created is unknown.

Black died a free man in Scotland in 1886 at around the age of 66.

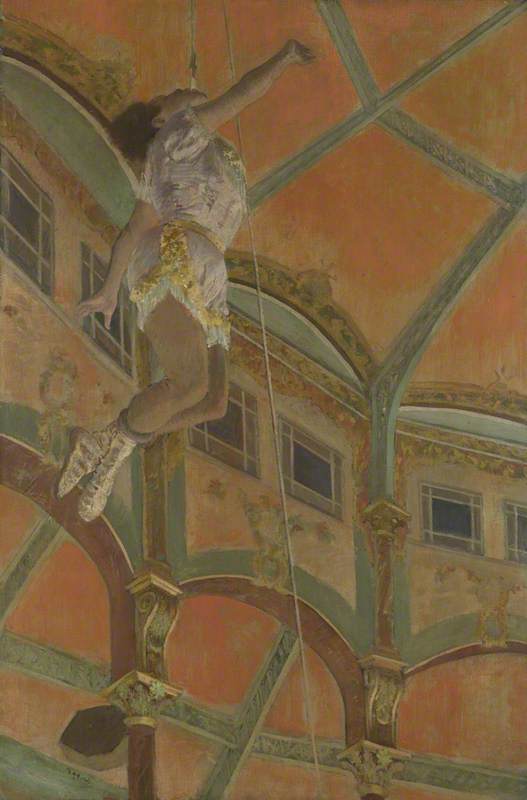

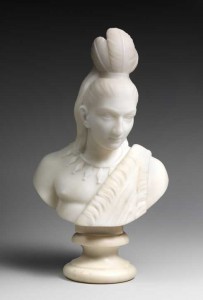

Miss La La/Olga Albertina Brown

The figure known as 'Miss La La' was Anna Olga Albertina Brown, born in modern-day Poland in 1858 to a black father and a white mother. Having been put in the circus by her mother at the age of nine, likely for financial reasons, she became an acrobat in Troupe Kaira, a travelling circus that performed in locations including the Royal Aquarium in London, the Gaiety Theatre in Manchester, and the Cirque Fernando in Montmartre, the backdrop for Degas' painting Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando.

The painting was made when Brown was around 21 years old, and we see her suspended by a rope attached to the rafters of the Cirque Fernando, 200 feet in the air, hanging on by her teeth – this was her signature performance.

Her other stage names included 'Venus of the Tropics' and 'African Princess', which reveal attempts by Parisian newspapers to create exotic marketing ploys. She was also called 'the Negress', 'Olga the Mulatto', 'La Mulatresse-Canon', the name most commonly used by British newspapers, and 'Black Venus'. All of these names place her race as the focal point, using words which are now derogatory, such as 'mulatto' and 'negress', but which exemplify the exoticisation of black figures at the time.

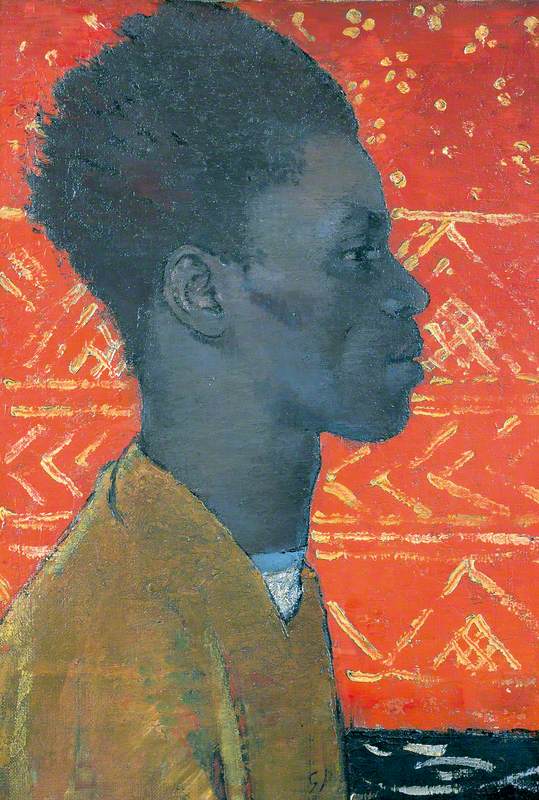

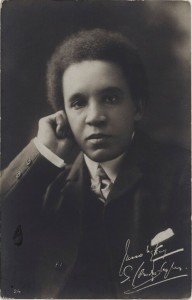

Henry Thomas

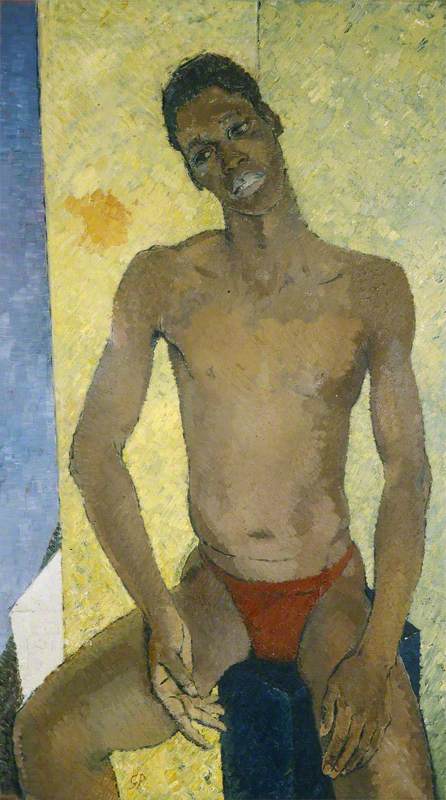

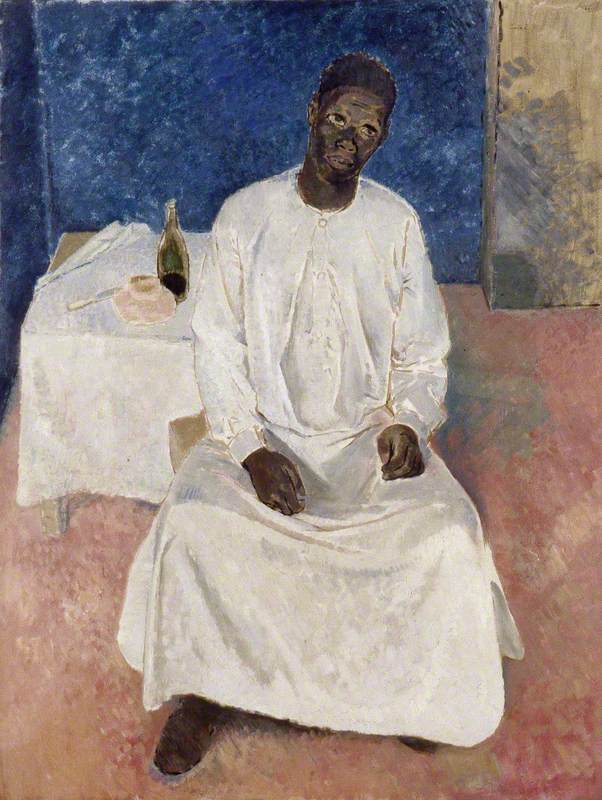

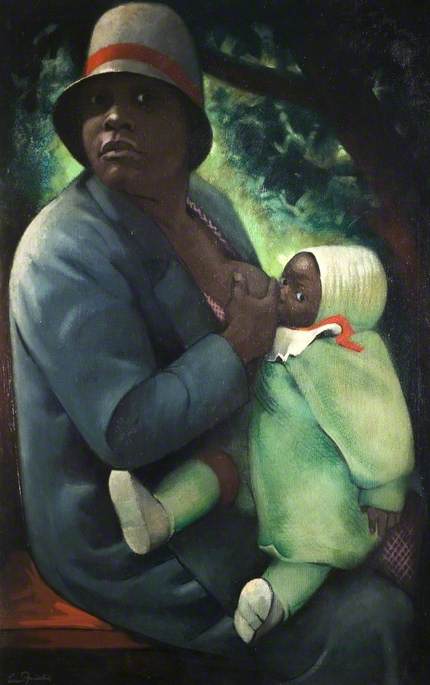

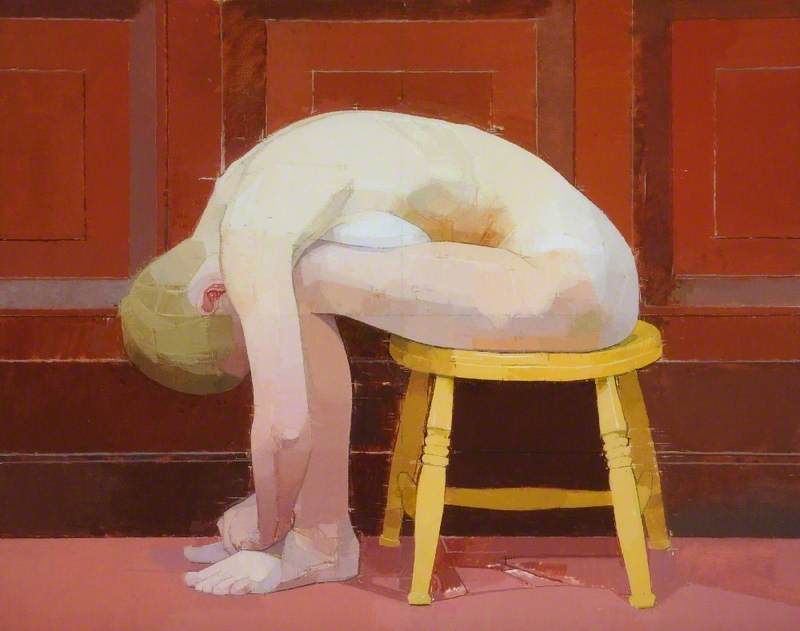

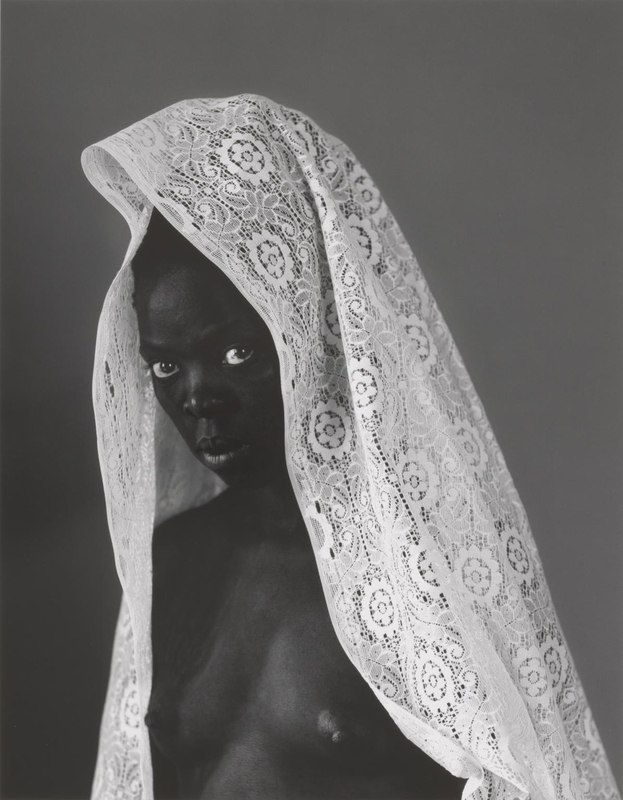

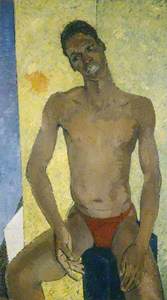

Henry Thomas was a servant and companion to Glyn Philpot, the artist for whom he posed on several occasions.

He is the subject of the painting Henry Thomas (1934–1935), and the works Melancholy Man (1936) and Man Thinking of Heaven (1937), both originally using the racist term 'negro' in their titles, amongst others. Henry Thomas was Jamaican and met Philpot in 1929, after missing his voyage back to Jamaica, and stayed working for him until Philpot's death in 1937.

It has been suggested that Philpot was able to project a more overt homoerotic gaze onto his portraits of Thomas than those of the white society figures who he also painted, particularly in Melancholy Man.

The languid semi-nude portrait, with Thomas' head cocked to the right, is intentionally effeminate and suggests that Thomas presented a suitable 'other' in the eyes of Philpot because his blackness distanced him from the heteronormative conventions of white society. The perception of the black body as an object allows for the subversion of the traditional male nude in a way that would not have been possible for Philpot to do with the white subjects of his other paintings.

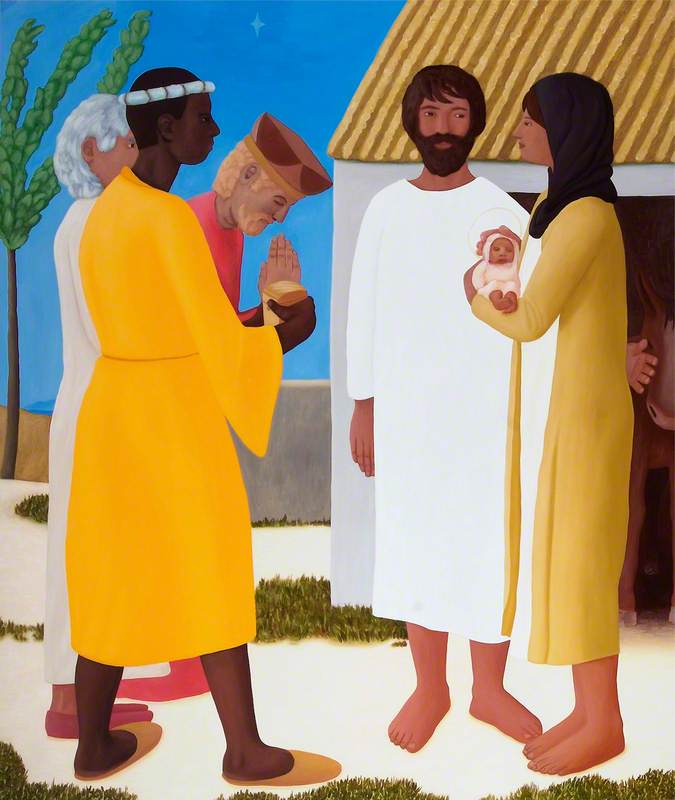

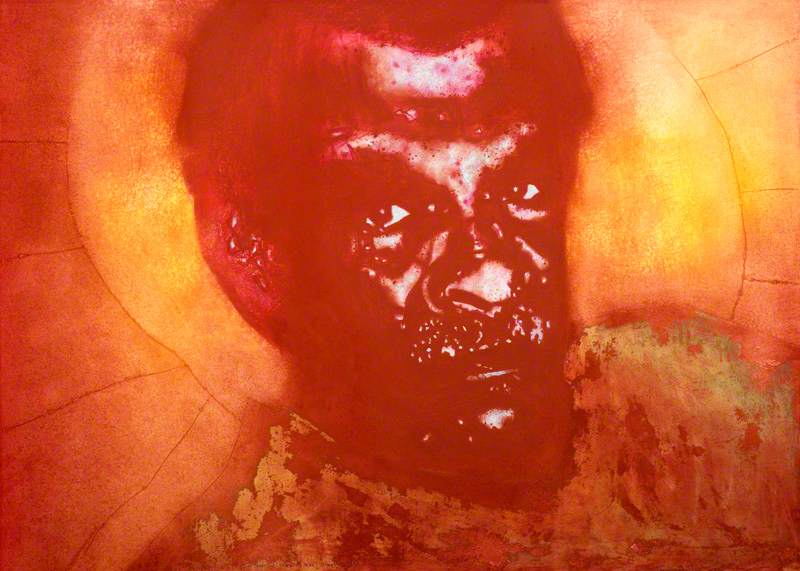

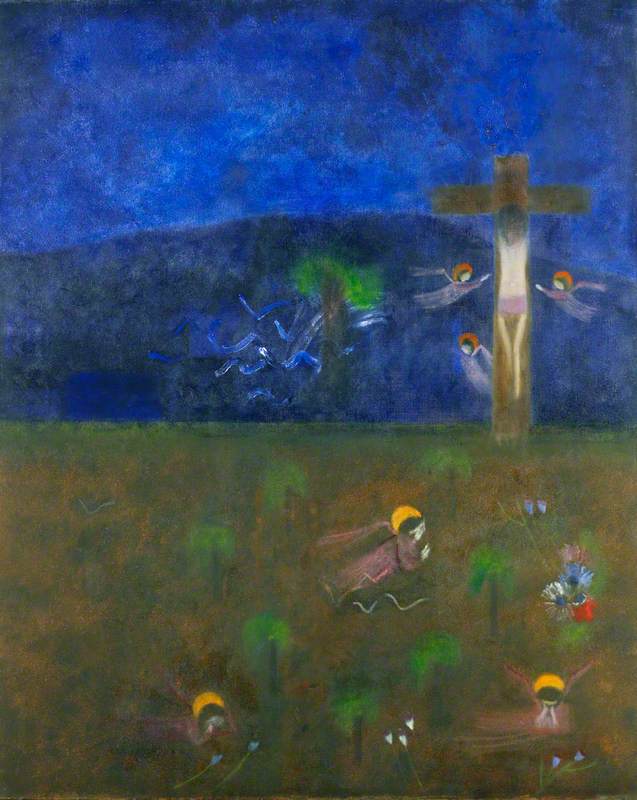

Georgeous Macauley

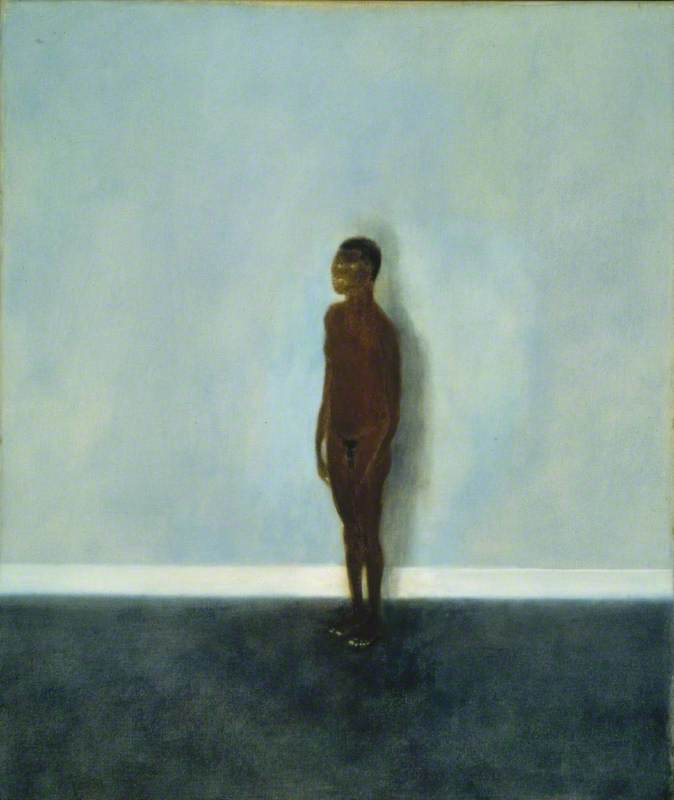

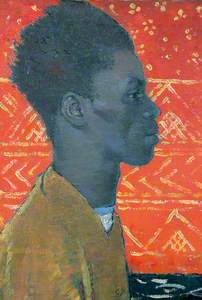

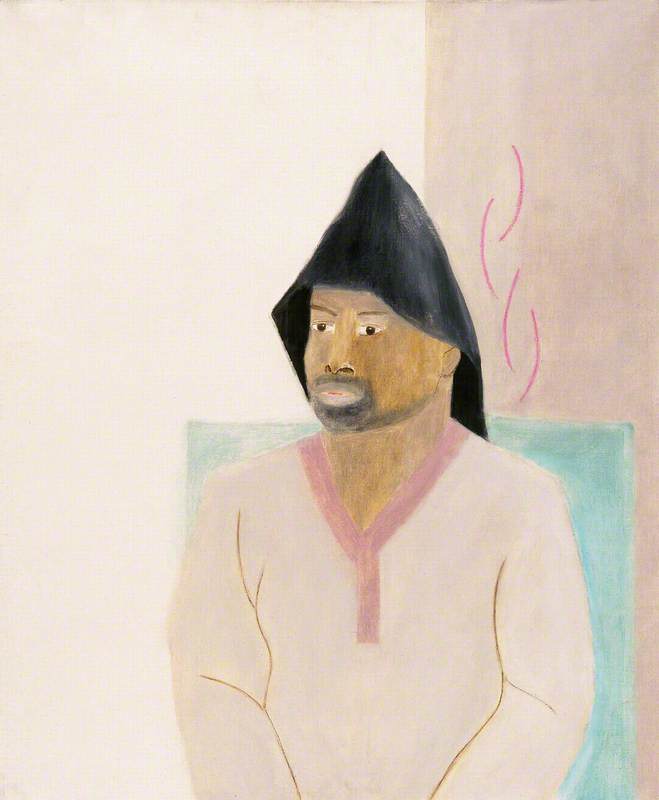

Little is known about Georgeous Macauley, the Nigerian man who modelled for the Scottish artist Craigie Aitchison, and it is the case that the identities of black models in art history are often unrecorded and left as 'anonymous' or 'negro' (as with the earlier example of Henry Thomas).

Nonetheless, we do know that Macaulay inspired a series of paintings, many of them nude, in the 1960s to the late 1970s. In Model Standing against Blue Wall (1962), the artist is clearly focused on the interaction of the colours, with the blue wall creating a stark contrast with the rich brown skin of McCauley, and there is little definition in the face. In the painting Georgeous Macaulay in a Sou'Wester (1976), there is more of an attempt at creating a likeness to Macaulay's appearance in the face, so it is closer to a portrait than Model Standing against Blue Wall.

Georgeous Macaulay in a Sou'wester

1976

Craigie Ronald John Aitchison (1926–2009)

The paintings discussed here are selected from a period spanning over 100 years. Whilst attitudes towards black figures moved towards being less diminishing, with figures being treated as more than just objects to create chiaroscuro like the unrecorded child in The Beloved, we still see the racist reduction of Henry Thomas, for instance, to simply 'Negro' in the original titles of works from the twentieth century.

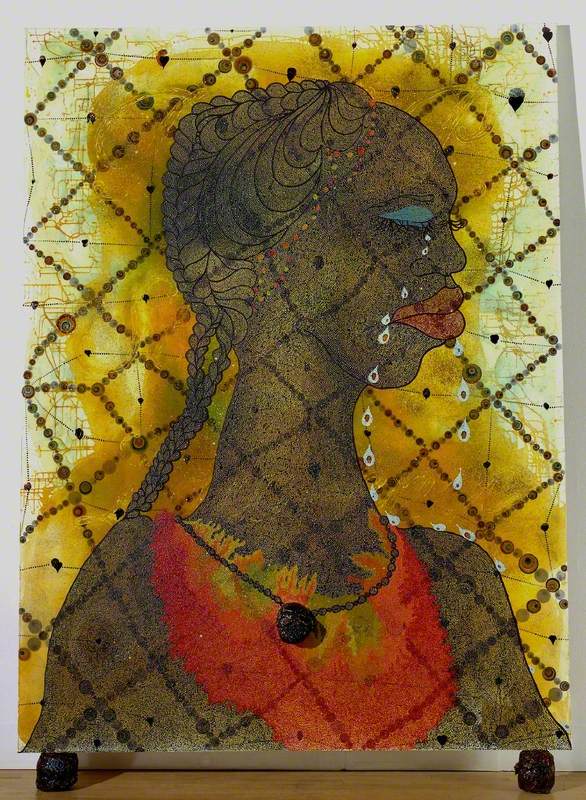

The practice of titling paintings in this way, still prevalent in many of the UK's public art collections, confines the black sitter to nothing more than their race, and strips them of their identity. With continued interest and research, more and more black sitters are being identified, at least by name, in art collections.

Alayo Akinkugbe, founder of @ablackhistoryofart

Further reading

Oswald Doughty and John Robert Wahl (eds), Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, vol. 2, Clarendon Press, 1965, pp.566–567

Dr Roberto C. Ferrari, 'From Sodomite to Queer Icon: Simeon Solomon and the Evolution of Gay Studies', Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 20, no. 1, 2001, pp.11–13

Jan Marsh (ed.), Black Victorians: Black People in British Art, 1800–1900, Lund Humphries, 2005

Denise Murrell, Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, Yale University Press, 2018

Pamela Gerrish Nunn, 'Artist and Model: Joanna Mary Boyce's "Mulatto Woman"', Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies, 1993

Virginia Surtees, The Paintings and Drawings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), Oxford University Press, 1971