Birmingham – the city that invented the electric kettle and the Balti curry, the hometown to UB40 and Black Sabbath, and the inspirational backdrop for The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings – is a city of creation and change.

Get to know Birmingham's history through works on Art UK.

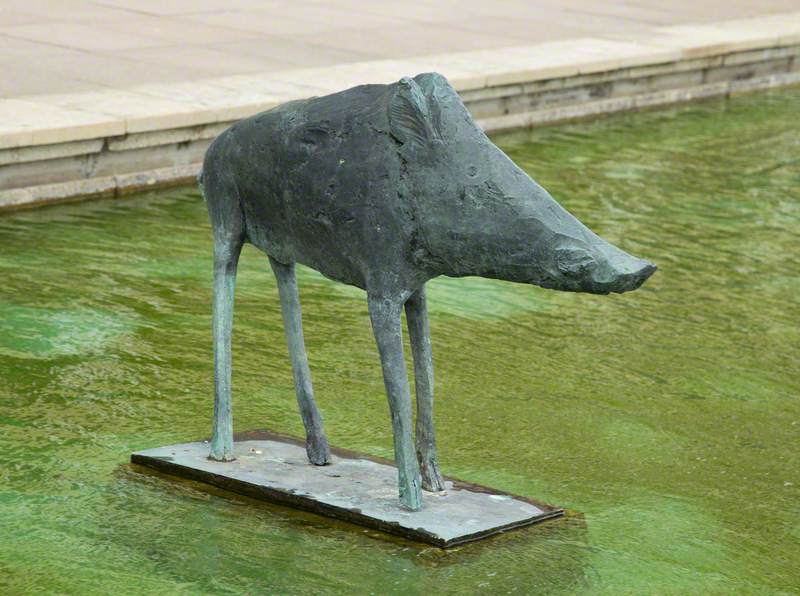

The River, Guardians, Youth, and Object (Variations)

1993

Dhruva Mistry (b.1957)

From town to city

What is now the second-largest city in the UK, Birmingham did not spring out of the ground in its current size. Beginning as a Saxon town, Birmingham would not be the city it is today without its market.

In 1166, the king permitted the town to hold a weekly market; a substantial annual fair followed this in 1250. By the Middle Ages, there were three significant markets. Fast forward to 2022, and the city is still very centred around its market, the Bullring.

Painted in 1820, this painting shows Birmingham as it became one of the country's largest and most important towns.

In the previous two decades, houses in the area were bought and demolished to lessen congestion, and in 1818 Street Commissioners began to provide gas street lighting, which can be seen in the painting. In the background is the church of St Martin, which still stands and is encircled by the Bullring shopping centre today.

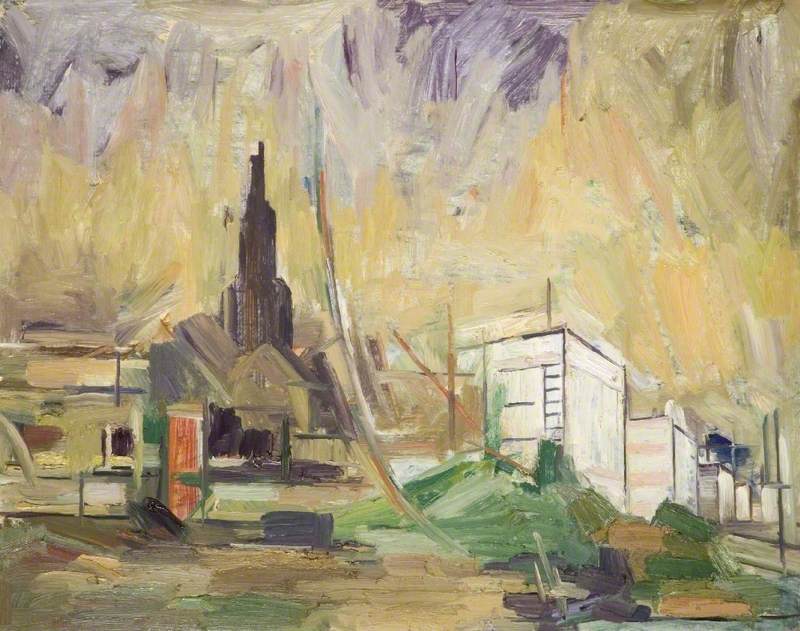

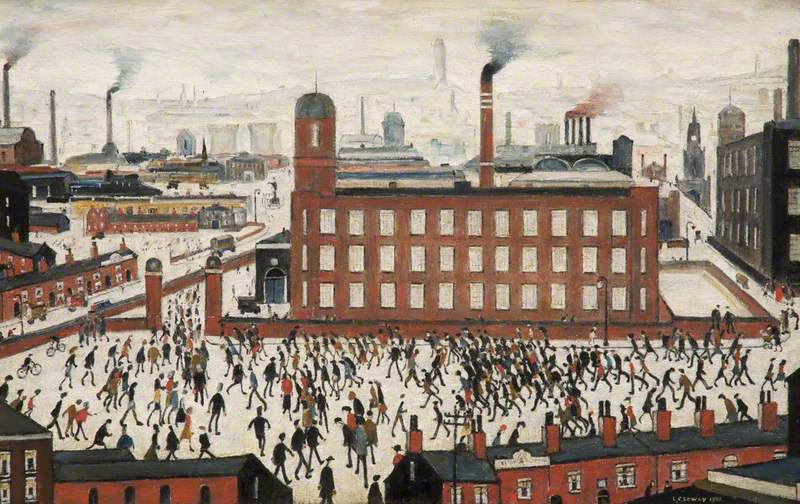

Industrialisation

Birmingham has a long industrial history. Much like its market, it wouldn't be the city it is without it. The Midlands and its urban landscapes consistently inspired painter Herbert W. Wright. This painting takes multiple aspects he deemed representative of the Black Country and brings them under one composition, from the large factories to the canals.

It's a fitting choice for an industrial history that spread across three centuries, marking the physical landscape and forever altering Birmingham, Britain and the world.

Birmingham was well placed to take advantage of all the ore and coal in its surrounds. The city fast became known as the 'workshop of the world' and 'the city of a thousand trades', making it a central component of British colonial and imperial endeavours. Birmingham was famous for producing guns, swords, glass, steam engines and fine jewellery. To this day, Birmingham has more canals than Venice due to the previous need for them in industry, and the highest number of inventions in the UK.

The Birmingham Political Union

Founded in 1830, The Birmingham Political Union (BPU) was intrinsic to exerting pressure on the Government for the Reform Bill of 1832. Established by Thomas Attwood, the BPU strove for more equitable representation for the lower and middle classes in government.

The first meeting was held in January 1830 and attracted over 12,000 attendees. A petition calling for parliamentary reform launched at the time garnered 30,000 signatures. Despite the support, the Bill was rejected.

Benjamin Robert Haydon's painting presents a demonstration two years later in Birmingham's Jewellery Quarter, which over 200,000 people and 40 unions attended.

The Meeting of the Birmingham Political Union

1832/1833

Benjamin Robert Haydon (1786–1846)

The Bill was finally passed that year. Despite having many faults, such as preventing women from voting and landowners still having a lot of influence, the Reform Act of 1832 was landmark legislation that led the way for further changes.

Empire and The Birmingham Improvement Scheme

Made of red brick, Victoria Law Courts on Corporation Street presents Birmingham's architecture and growth, and it was in this period that red brick was pioneered. The figure of Queen Victoria by Harry Bates sits centrally on the façade.

Much like the Birmingham coat of arms, on the left gable are figures of Art and Craft and on the right figures of manufacture and engineering – gun-making and pottery.

Gun manufacture was one of Birmingham's leading trades in the eighteenth century, with 100,000–150,000 guns shipped to Africa annually in exchange for enslaved people. This production continued into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, producing weapons for the extension of empire and the world wars – and made Birmingham wealthy. Birmingham also produced shackles and other items used to control enslaved peoples.

The Law Courts were part of The Birmingham Improvement Scheme which saw slum housing destroyed and replaced by civic buildings and wide roads. Joseph Chamberlain, formerly mayor and then MP and founder of the University of Birmingham, played a leading role in the Improvement Scheme and centred Birmingham in the empire's activities.

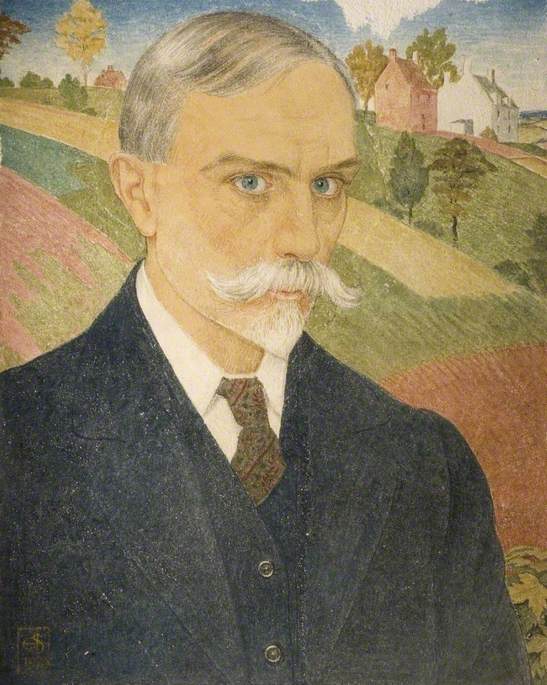

The Right Honourable Joseph Chamberlain (1836–1914), PC, MP

c.1900

Nestor Cambier (1879–1957)

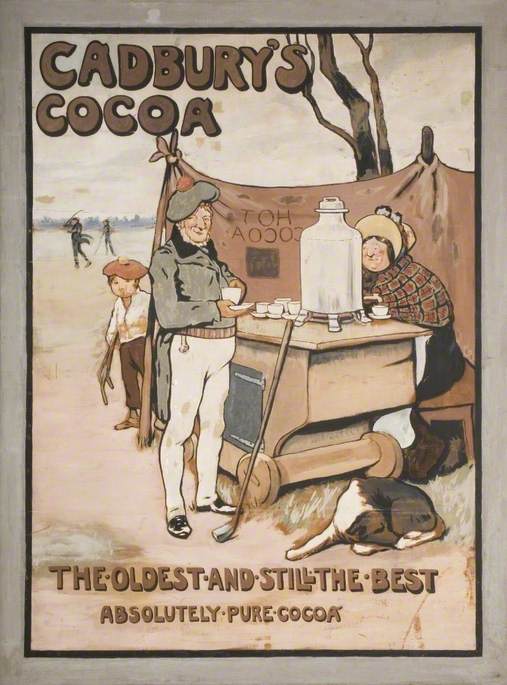

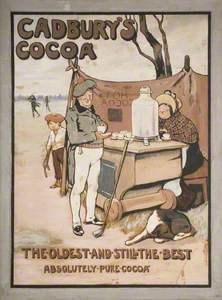

Cadbury's

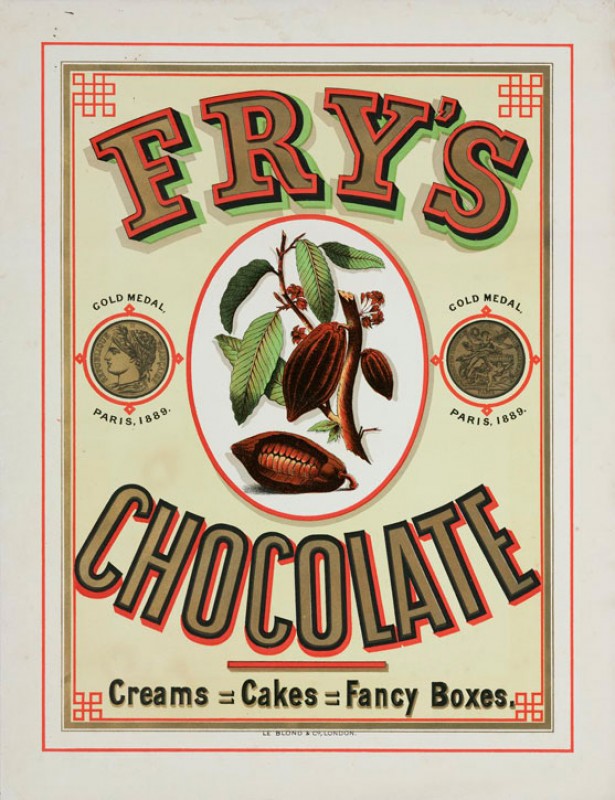

A whistle-stop tour of Birmingham's history wouldn't be complete without attention to Cadbury's. In 1824, John Cadbury, a Quaker, opened a grocery store selling cocoa and drinking chocolate as an alternative to alcohol, which he deemed a social scourge. Seven years later, he would open a factory.

Growing year on year, the factory moved to various locations, at one point on Bridge Street, in the city centre, so that the factory could have its private canal spur to all the major ports in Britain. The factory is now in Bourneville. As Quakers, the Cadbury's were active philanthropists with profits channelled into local, national, and international social causes addressing poverty, and education inequalities, amongst other areas.

The positive impact of the Cadbury family's philanthropy at the time is still felt and seen in the city today. George Cadbury was also an outspoken critic of imperialism and Birmingham's role within it. Working with a local artist, Cecil Aldin, in the 1890s, Cadbury's produced one of the most recognisable ads and imagery at the time with posters across Britain.

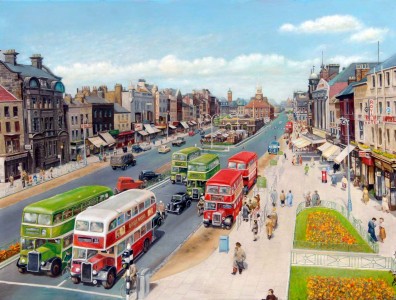

Post-war Birmingham

The early twentieth century saw a lot of change in Birmingham. It was the third most bombed city in the UK during the Second World War, with the Bull Ring, arms factories and housing destroyed. Post-war construction led to high-rise flats replacing nineteenth-century back-to-back brick housing, often seen as slums. Spaghetti Junction was also built.

With the expansion of the central government, Birmingham lost much independence, with many decisions about its post-war growth being made in London. During the 1930s, 'from Westminster's point of view [Birmingham] was too large, too prosperous, and had to be held in check.'

Despite this, Birmingham still grew and also became the home to many people from Ireland, Caribbean Islands and the Indian subcontinent. Promises of jobs and training let down many people who moved to the UK at the time, and discrimination was a reality; Birmingham was no exception.

Franklin White's work captures Birmingham at the time, its thick and quick brush strokes expressing the speed and size of changes Birmingham felt in its architectural and social landscape in the twentieth century.

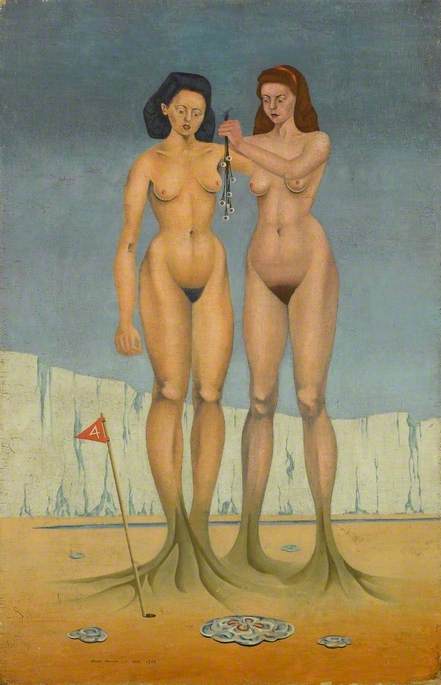

Discrimination and riots

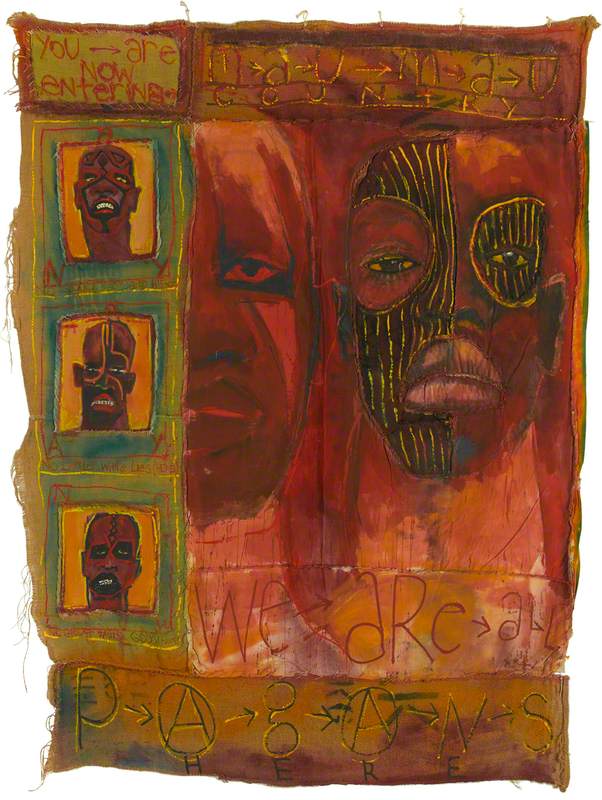

Pogus Caesar was born in St Kitts, West Indies, and grew up in Birmingham, becoming a photographer, artist and archivist. Caesar is known for photographing the Handsworth Riots of 1985. The Handsworth Carnival's annual celebration gathered people from communities across Birmingham. In September 1985, after a weekend of carnival, a riot started in response to the arrest of an African Caribbean man for a traffic offence.

Although this painting is not one of Caesar's photographs taken during the two-day riots (it was painted three years earlier), this work presents the undercurrent of hostility and violence towards Black people in the city, particularly the police and authorities' role in it. A riot had also occurred in Handsworth in 1981 alongside those in other cities across the country, a year before this painting was made.

Birmingham today

Known to Brummies as 'The Floozie in the Jacuzzi', the central figure in Dhruva Mistry's sculpture sits surrounded by fountains in Birmingham's Victoria Square, with other sculptures by the artist representing youth and eternity.

The River, Guardians, Youth, and Object (Variations)

1993

Dhruva Mistry (b.1957)

Finally running again, the fountain is a central point in the city and was restored in time for the Commonwealth Games taking place this year. The square will be the finishing point for the Marathon races.

The Floozie is joined by other sculptures that all speak to Birmingham's history. Recently returned to the square, Antony Gormley's Iron:Man represents Birmingham's Industrial Revolution.

Earlier today Antony Gormley’s artwork Iron: Man was finally back on full display in Victoria Square. The artist sent this message to welcome the much-loved landmark back to the of #Birmingham. #BeBoldBeBham pic.twitter.com/27oPk160M2

— Bham City Council (@BhamCityCouncil) March 8, 2022

Dating to 1901, a statue of Queen Victoria by Thomas Brock looms over the square.

Queen Victoria (1819–1901)

1901 & recast 1951

Thomas Brock (1847–1922) and William James Bloye (1890–1975)

Artist Hew Locke has expertly reimagined the statue of Queen Victoria for the Commonwealth Games. Entitled Foreign Exchange, the original Victoria is joined by five others in a boat as they head out to other areas of the empire to promote the Queen.

Foreign Exchange

(temporary installation) 2022

Hew Locke (b.1959)

Perhaps the hardest artwork to choose is the one for Birmingham's current moment. Benny's Babbies was made by a Birmingham artist, Christopher Spencer, at the request of the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Working on his phone and iPad, Spencer usually shares satirical and comedic works on Twitter (as @coldwarsteve).

In 2019, Spencer was asked to create a work in response to the museum's collections. The work brings together all the people and places Spencer loves about Birmingham, from the Rotunda to Mr Egg, Barbara Walker MBE to Joe Lycett, and Birmingham's contributions to British culture.

On this day a year ago we proudly unveiled Benny's Babbies, the amazing piece @Coldwar_Steve. It was supposed to be going up @BM_AG but instead we worked together to create an online launch w/ contributions from @joelycett @KitdeWaal @jonathancoe + more!https://t.co/5wShkk0T7g pic.twitter.com/VAltE6uGFS

— The Social (@thesocial) April 18, 2021

This work was also chosen for the current exhibition at the museum, 'We Are Birmingham', curated by six young people of colour from Birmingham working with the programme Don't Settle. Very Brum, this work says it all, and the pride everyone in the city has for it.

Olivia Peterson, freelance writer and Birmingham local