The little, winged angels at the feet of Raphael's Sistine Madonna from 1513–1514 are perhaps the most famous pair of cherubic figures in Western art history – and yet, they're the smallest figures in the painting, looking up from the edge of the canvas towards the primary subjects of Mary, Jesus, and Saints Barbara and Sixtus.

Sistine Madonna

c.1512–1513, oil on canvas by Raphael (1483–1520)

Their pensive features have been replicated in art, on any kind of souvenir you can think of, and even on a 1995 US stamp. So what do these small, symbolic figures mean in Western art, and why does their popularity endure?

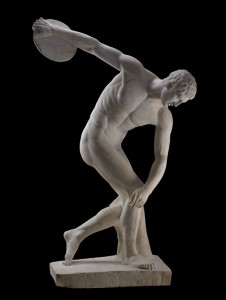

The tradition of frolicking, allegorical children in art is a long one. The infant, male, typically winged putti figures first symbolised earthly passions, deriving their role from the Greco-Roman god of love and desire, Eros/Cupid. Before it graced an international gelato logo, the winged, male amorino – a type of putto – brought amorous associations with Cupid to works of art.

Cupid was most often depicted as a child or youth, and usually in a roguish or moralising narrative. Lucas Cranach the elder's painting from around 1525 shows a scene from an ancient Greek poem, in which the infant Cupid complains to his mother Venus, the goddess of love, about being stung by a bee. Even the god of love must learn the lesson that seeking pleasure can bring pain.

Cupid complaining to Venus

about 1525

Lucas Cranach the elder (1472–1553)

A famously enigmatic Mannerist painting by Bronzino (1503–1572) features Cupid in an erotic pose with Venus, and numerous works depict his legendary seduction of Psyche.

An Allegory with Venus and Cupid

about 1545

Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572)

Whenever Cupid appears in art, whether as a central or background figure, he brings connotations of love or licentiousness, serving as a popular and long-replicated visual cue.

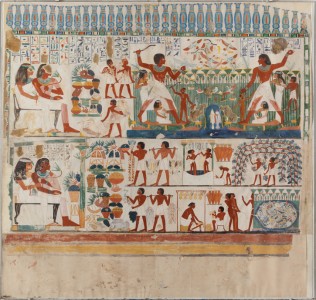

Early putti, for their own part, decorated classical architecture and sarcophagi as tutelary spirits, and were often depicted participating in spirited Bacchic rites and harvests. Christians reinterpreted these scenes to represent the biblical meanings of wine through its role in the Eucharist.

A Bacchic Procession of Putti

1660

Jerome Hesketh (active 1647–1666) (probably)

In the Renaissance, putti were revived within the Christian context as angelic spirits to serve as onlookers in religious scenes as well as representative figures in secular works. Looking to ancient Greek and Roman art, quattrocento sculptors such as Donatello began to create decorative, sometimes enigmatic putti and spiritelli – sprites that could be either angelic or impish. These beings, derived from the Hellenistic intermediary spirits known as 'daemons', symbolised a fusing of traditions and could bring fright, folly, or passion to a narrative work of art.

Putti's presence in a larger painting or sculpture often sets the tone for the audience, their iconography shifting based on the composition – sacred or secular – and their individual expressions. They could imply shades of divinity, prosperity, or eroticism, as the work demanded. They may model faithful adoration of the Christ child – as in the work below – or symbolise moral values, nature, or the arts in allegorical works.

The Madonna and Child with Two Adoring Putti

late 17th C

Carlo Maratta (1625–1713) (attributed to)

The frolicking, fruit-bearing figures in an early seventeenth-century allegory of Earth by Jan Brueghel the younger and Hendrik van Balen I represent the bountiful aspects of nature, while putti in several French-inspired paintings at Hinton Ampner in Hampshire showcase the fields of music and architecture.

The Four Elements: Earth

c.1625/1632

Jan Brueghel the younger (1601–1678) and Hendrik van Balen I (1575–1632)

Playful putti came into their own in early eighteenth-century Rococo works, in which they bask in the flower-filled pastorals that were more sensuous and lush than angelic and demure. These mischievous, rose-pink figures appear frequently in French painter François Boucher's works and those of his followers, such as an allegory of fire in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Though putti are often confused with cherubs, which today are synonymous with chubby, rosy, innocent infants, the angelic cherubim were first interpreted from a passage in the Book of Ezekiel as supernatural beings with hooves, wings and four faces – human, lion, ox and eagle. Their role and rank among the orders of angels differs among the Jewish, Christian and Islamic traditions.

The Hebrew Bible describes two gold cherubim on the lid, or mercy seat, of the Ark of the Covenant, a sacred relic which was built to hold the tablets Moses received from God and has been visually interpreted in numerous illustrations and paintings.

The Israelites Passing over the Jordan with the Ark of the Covenant

c.1640

Frans Francken II (1581–1642)

The Ark Passes Over the Jordan

(c.1896–1902), gouache on board by James Tissot (1836–1902)

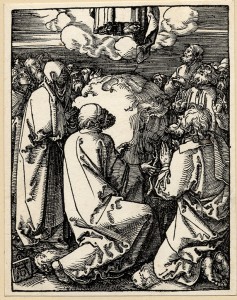

In the Christian tradition, cherubim are the second highest order of angels after seraphim. While early Byzantine depictions included their chimeric characteristics, European ones soon simplified them into winged corporeal representations, as in two panel paintings from 1370–1371 by Jacopo di Cione in The National Gallery, London.

Seraphim, Cherubim and Adoring Angels: Left Pinnacle Panel

1370-1

Jacopo di Cione (c.1320–1400) (and workshop)

In the Middle Ages and early Renaissance, cherubim were frequently depicted in blue, symbolic of heavenly knowledge, while seraphim, which were associated with fire, appear in red. Here they are depicted in robes of their characteristic colours and placed hierarchically above other orders of angels.

Seraphim, Cherubim and Adoring Angels: Right Pinnacle Panel

1370-1

Jacopo di Cione (c.1320–1400) (and workshop)

Another visual tradition saw these angels depicted entirely as red or blue beings, perhaps most iconically in the right-hand panel of Jean Fouquet's (c.1420–1481) Melun Diptych from around 1450 of the Virgin and Child Surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubim. The angels' red and blue bodies contrast dramatically with the stark white flesh and outer robes of the Madonna and Christ child.

Virgin and Child Surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubim (Melun Diptych)

1452–1458, oil on panel by Jean Fouquet (c.1420–1481)

'There is a flavour of blasphemous boldness about the whole', Dutch historian Johan Huizinga wrote of this painting in The Autumn of the Middle Ages (1919). 'The bizarre inscrutable expression of the Madonna's face, the red and blue cherubim surrounding her, all contribute to give this painting an air of decadent impiety in spite of the stalwart figure of the donor.'

Though Fouquet's Madonna may have been among the more sensual versions, cherubim typically did lend an air of piety to a piece. Cherubim and seraphim shape the mandorla (almond-shaped aureole) behind an early fifteenth-century Italian Madonna in the collection of Christ Church, Oxford, encircling and emphasising her holiness.

The Virgin with the Child, in a Mandorla of Winged Cherubs' Heads, Saints and Musical Angels

Mariotto di Nardo (active 1394–1424) (studio of)

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, cherubs' presence often served to indicate the divinity of more intimate, humanistic portrayals of the Holy Family, like this 1627–1632 depiction from the studio of Anthony van Dyck.

They can also be found crowning or otherwise accentuating depictions of saints.

Saint James Major and Saint Catherine of Alexandria

c.1565

Orazio Samacchini (1532–1577)

Some lore, stemming from varied Biblical interpretations, suggests that the Christian devil was once an angel that fell from grace. A debated passage in Ezekiel (28:11–19) describes the King of Tyre as a 'guardian cherub' expelled from heaven for his wickedness. While the link from cherub to Satan seems tenuous, there is an admitted ambiguity among the angels as the conventions of their depictions and mythology evolved through the centuries.

Distinguishing putti from cherubs became complicated as the latter's form evolved towards winged infant and Christian and Greco-Roman iconography became intertwined.

Inspired by Rococo fashion, putti or cherubs also became a popular icon on American colonial grave markers in the eighteenth century, a seemingly cyclical return to the use of classical putti on sarcophagi – but, as scholar Adam R. Henrich argues, with perhaps more stylistic than religious meaning.

Though their meanings have merged and mutated, small, angelic, winged figures still carry significant visual import. In this 1918 portrait, cherubs appear in the celestial roundel that haloes the head of Miss Dorothy Brook, calling on the Christian iconography to suggest her innocence and beatific talent as she plays the violin.

Though often confused, equated, or intermingled today, each winged figure derives from a distinct tradition. Cherubim are Biblical angels, now commonly interpreted as pudgy winged babies; putti are frolicking children with varied meanings; amorini are Cupid's minions, and Cupid is a Greco-Roman god with myriad legends who has been distilled into a baby archer in popular culture. It's quite a journey from divine being to cute décor.

Anne Wallentine, writer, editor and art historian

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Charles Dempsey, Inventing the Renaissance Putto, UNC Press, 2015