This article is an introduction to Bernard Meadows (1915–2005) via his figurative sculptures. Like so many of his generation, Meadows served in the Second World War, and his work can now be seen as an inquiry into a much reshaped humanity. His sculptures probe what it means to be human, whether that is physical, emotional or ethical.

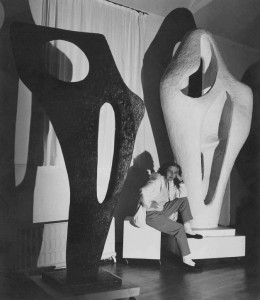

Born in Norwich in 1915, Meadows studied painting at Norwich School of Art between 1934 and 1936. In 1936, he and two fellow students visited the Hampstead studio of Henry Moore (1898–1986), and Meadows, who was becoming more interested in sculpture, took an example of his work along with him. Moore was so impressed that the next day he sent a postcard and offered Meadows a role as his first assistant – a role he took on while studying at the Royal College of Art.

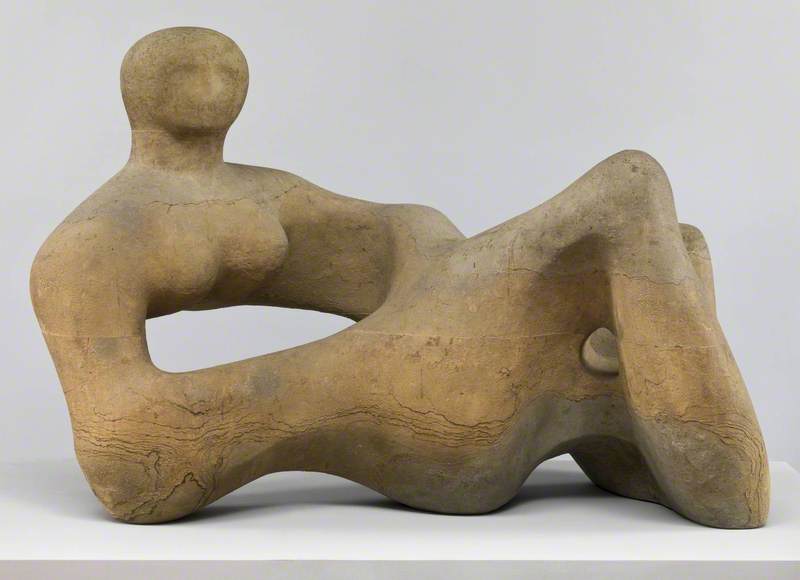

It became an enduring relationship; he was trusted with the majority of Moore's carving, studio photography and documentation. The first significant Moore sculpture worked on by Meadows was Recumbent Figure (1938), carved in Horton stone.

Following their inclusion in the 1951 Festival of Britain, sculptures by both artists were exhibited together at the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1952, alongside others including Reg Butler (1913–1981), Lynn Chadwick (1914–2003), and Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005). Moore was displayed outside the pavilion, strategically positioned as the 'parent of them all'.

This new generation of sculptors would become grouped under the term Geometry of Fear, a phrase used by the critic Herbert Read to describe how these artists were responding to anxieties felt in the aftermath of the Second World War.

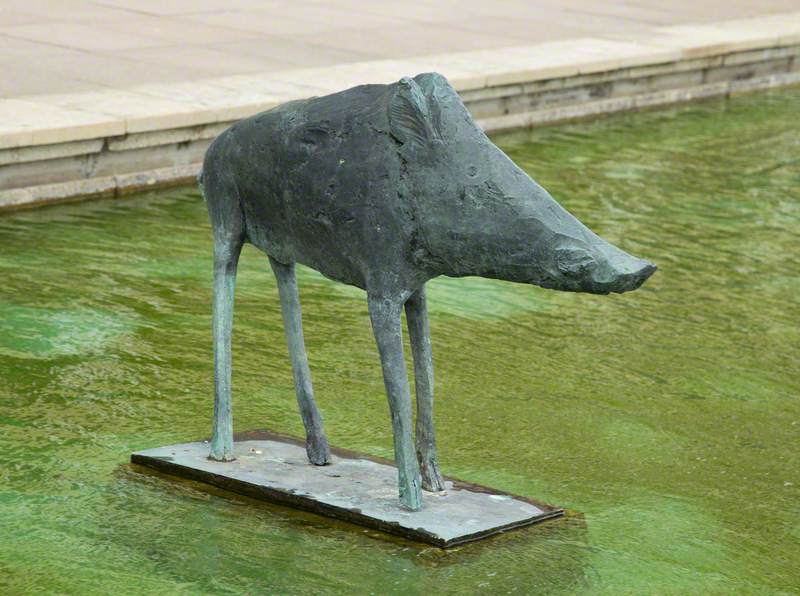

Included in the display was Black Crab (1951–1952), a work inspired by crabs that Meadows saw on the Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean, where he was stationed while serving in the Royal Air Force between 1943 and 1946 – before and after which he studied at the Royal College of Art. In 1960, he was invited to become the RCA's Professor of Sculpture – where his pupils included Elisabeth Frink – following 12 years teaching at Chelsea School of Art.

Interestingly, Meadows said he looked 'upon… crabs as human substitutes', and initially, he had actively engaged with animal form – birds and cockerels were favourite subjects – as a means of positioning his work as distinct from his mentor. However, Moore had instilled in his assistant a lasting interest in the boundaries of bodily form, and this theme would continue throughout Meadows' career.

Meadows' first major commission was a figurative group for the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in October 1954. The foundation stone of Congress House, its new headquarters on London's Great Russell Street, was laid in the same year, and a 'sculptural competition' was launched to find suitable artists to create two new sculptures for permanent display at the main entrance and internal courtyard.

Meadows was selected from more than 70 applicants in his category, which included entries from Siegfried Charoux (1896–1967) and Peter Laszlo Peri (1899–1967), the latter receiving a commendation. Jacob Epstein (1880–1959) was also chosen for his memorial commemorating trade unionists who were killed during the two world wars.

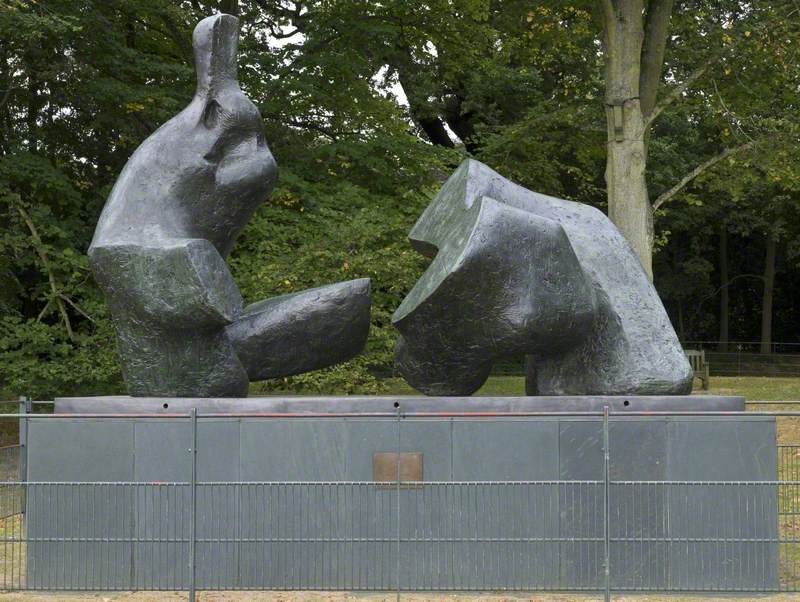

In his initial proposal, Meadows describes how his sculpture, The Spirit of Brotherhood (1958), would represent 'the triumph of good over evil… the strong helping the weak'. It remains on view above the entrance of Congress House today and depicts two semi-clothed male figures: one has fallen to the ground, the other extends a helping hand to his friend, pulling him upwards by the elbow. It is a robust yet tender demonstration of comradeship and togetherness.

The commission is certainly Meadows' most 'traditionally' figurative sculpture, and its sentiment is comparable to Moore's Harlow Family Group (1954), which was conceived the same year.

When compared to The Spirit of Brotherhood, works by Meadows such as Jesus Crab (1954) and Fallen Bird (1958) are much more characteristic of his overall practice, and they continue to demonstrate the indisputable influence of Moore.

This affinity is evident if we see these two sculptures alongside Moore's Mother and Child (1953) and his Falling Warrior (1956–1957).

These works can be understood as investigations into the points where the human and animal meet and are therefore representative of the inhumanities of the recent war. Indeed, Meadows was 'obsessed with the representation of fear', and had read extensively on Existentialism, a philosophical inquiry into the meaning and value of human existence, with its emphasis on ideas of isolation and anxiety.

It is unsurprising then that Meadows favoured the lone figure, clear in his Seated Figure (Cross-Legged) (1962), Pointing Figure (1967) and Frightened Figure (1976).

In these examples, Meadows reimagines human anatomy by presenting androgynous figures as machine-like and robust in different ways. Seated Figure (Cross-Legged) is protected in what appears to be a thick armoured cocoon, its spindly legs the only recognisable hint of the human shrouded within.

Pointing Figure is the cowering witness to barbarity, and Frightened Figure is throwing its arms up in horror. Its head is devoid of all features other than a single hole, which could be either a screaming mouth or an eye wide-open. Its body, just like that of Pointing Figure is highly polished and bulbous. Its limbs are cut short, and it appears functional, as if repurposed to become a machine component.

In these works, Meadows aims to demonstrate the complex collective psyche of the post-war world, and a comparable sense of threat is seen in his standing figures, including Little Augustus (1962) – part of his warrior series inspired by a trip he took to Italy in 1960 where he studied heavily armoured Renaissance statues – and Standing Man (c.1972).

These can be read as battle-hardened warriors with their stone-like armoured torsos, but also as human beings petrified, both bodily and psychologically.

In his later life, Meadows hinted at the difficulties of separating his work from Moore. But their productive working relationship corresponds with the fellowship demonstrated in The Spirit of Brotherhood: together they were stronger, and they positively informed the progression of each other’s sculpture.

Meadows is, however, set apart by his steadfast thematic consistency, and it can be argued that all of his work is concerned with characterising fear and anxiety. This is seen through a distinct and vigorous visual language, and none more so than in his figurative sculptures.

Dr Matthew Retallick, art historian and curator

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation