Fear of the dentist is one of the most common phobias in Britain today and, according to a study by the British Dental Association, around a third of people who don’t regularly visit their dentist cite anxiety as the main cause. Despite the fact that modern dental treatments are gentler than 30 years ago, and in many cases virtually painless, new anaesthetic techniques have reduced the pain of the injection and the whole experience is designed to ‘feel’ less stressful, many people still recall the sights, smells and experiences of their childhood, leading some to avoid the dentist altogether.

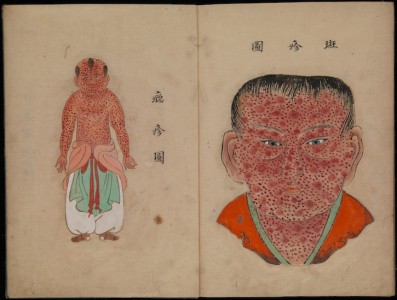

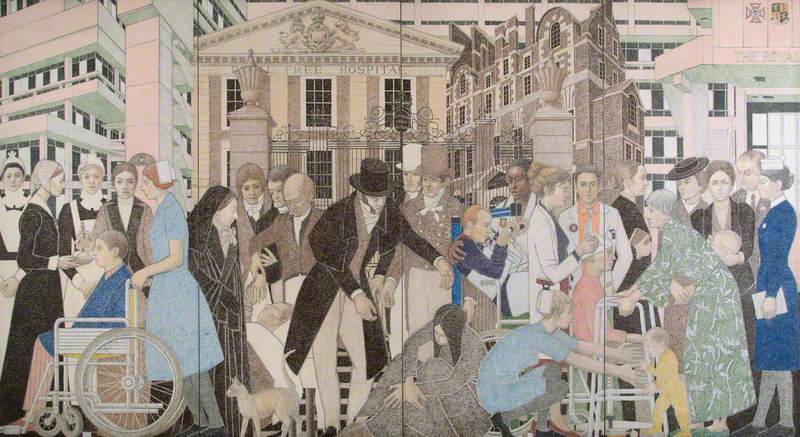

Historians these days are generally reluctant to think of history in terms of progress or as a linear path from ignorance to enlightenment. The history of medicine (the area in which I specialise) was certainly one where stories of medical discoveries and ‘great men’ doctors used to predominate. In some cases, however, it is difficult not to look back and say a silent word of thanks that you don’t live in the period you study. The treatment of teeth in the past is definitely one of those cases.

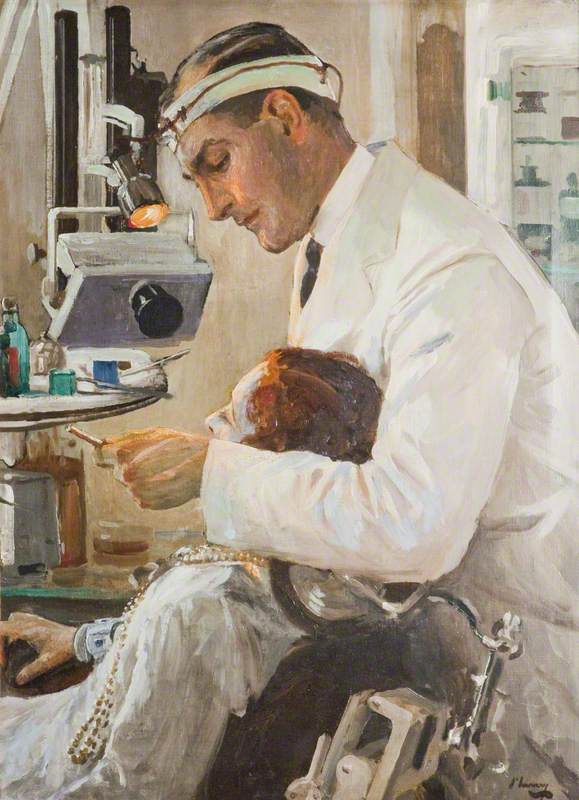

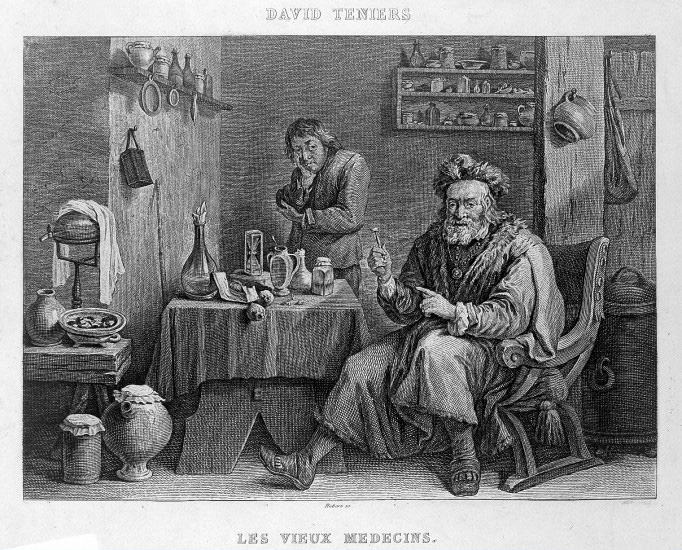

Compared to some medical occupations, dentistry is a relative newcomer. Before the late eighteenth

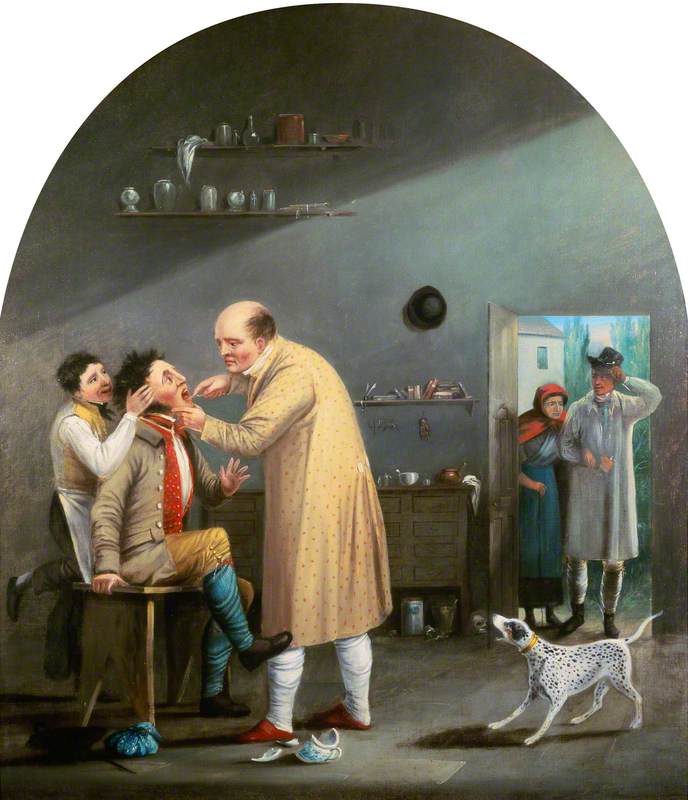

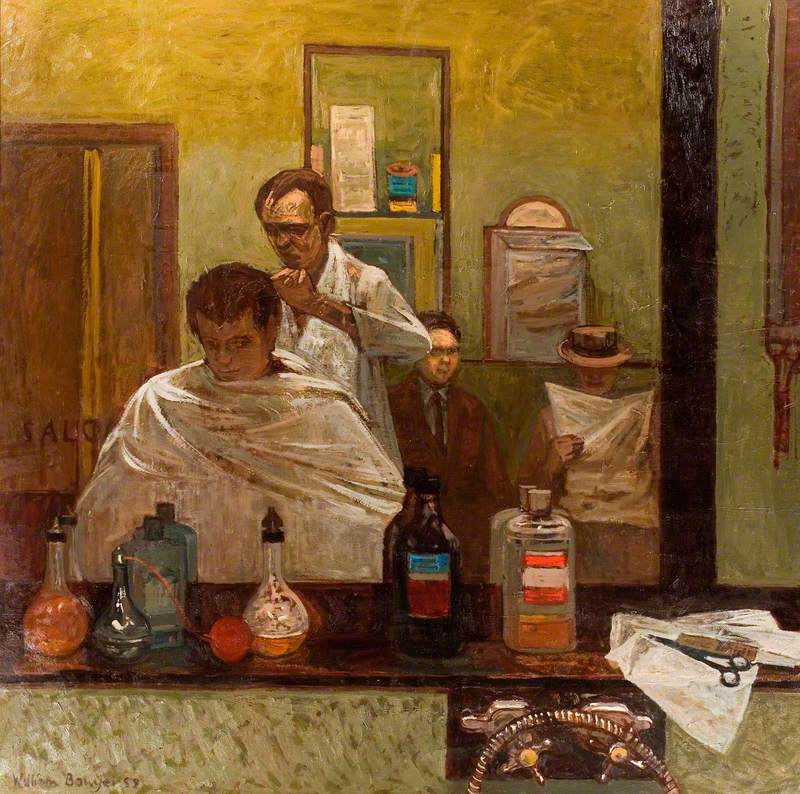

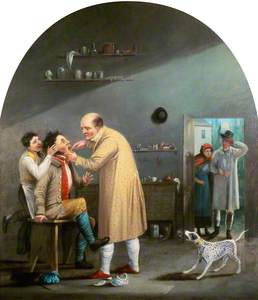

Until the mid-eighteenth century, perhaps the main providers of dental services were barber-surgeons. Before they split to form separate companies in 1745, barbers and surgeons were effectively one

What would it have been like to have a tooth pulled before anaesthetic? A range of equipment was certainly needed. Dental ‘keys’ were used to lever teeth out or even break them into pieces! Some good examples of keys can be found on the ‘All Things Georgian’ blog here. If all else failed, some dental forceps also had a steel ball on the end of one handle, used to smash the offending tooth out and end the unfortunate patient’s ordeal.

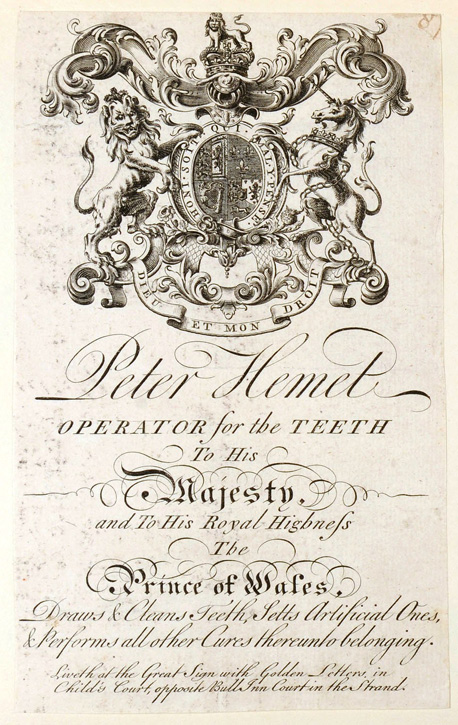

George III’s ‘Operator for the Teeth’, Thomas Berdmore, gives us some idea of what the experience could be like in his Treatise on the Disorders and Deformities of the Teeth and Gums of 1770.

Members of the royal family with

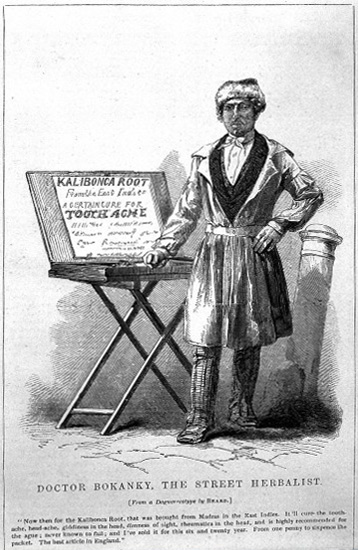

Aside from formal practitioners, however, there were ‘specialist’ tooth-drawers, who professed to have superior knowledge of dentistry, and who advertised themselves as a pain-free alternative to surgeons. In 1716, for example, one Mr Reed could be found at the ‘Crooked Stocking’ in Gray’s Inn Lane, London, ‘at which place you may be

Given the pain and understandable fear engendered by the

Another dubious preparation for sale in the early eighteenth century was the ‘Tincture

Tooth-drawers were also prominent amongst the cast of itinerant pedlars, mountebanks and

This is not to say that all dental practitioners were regarded as quacks. Indeed, many were clearly held in high regard. In a letter to the London Mercury in April 1721, one Elisha Crusoe of Cricklade, Wiltshire, was referred to as ‘an eminent tooth-drawer’. In August 1715 was reported the death of a certain Mr Smith, ‘the Famous tooth-drawer’ in London.

It is worth sparing a thought for our predecessors, who endured untold pain and misery at the hands of pre-modern dentistry. Next time you’re sitting in the dentist’s waiting room too, be thankful for anaesthetic and the modern preference for saving, rather than removing, teeth, wherever possible. Things were NOT always better in the past!

Dr Alun Withey, Wellcome Research Fellow, University of Exeter

Find Alun on Twitter: @DrAlun