Known alternately as 'the uncrowned queen' of Great Britain, or – as famous diarist John Evelyn termed her – 'the curse of the nation', Barbara Villiers remains one of the most divisive and fascinating women of the Restoration.

The most long-lasting of Charles II's mistresses, at the apex of her influence she freely helped herself to money from the Privy Purse, was given all of the king's Christmas presents, had a massive feud with her lover's wife, the Queen, about being appointed her chief lady-in-waiting (Barbara won that one), and not only accompanied the king and his bride on their honeymoon to Hampton Court – but really emphasised her position by giving birth to the king's child there.

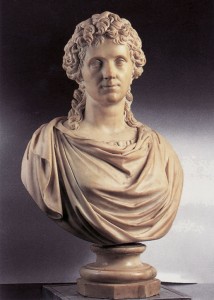

Barbara Villiers (1640–1709), Duchess of Cleveland

Peter Lely (1618–1680) (after)

Barbara was born in 1640, two years before the advent of the Civil War. Her aristocratic family was staunchly Royalist, and her father would go on to be killed in battle early in the war. After the Royalists were defeated, Barbara would later recall that, during the years of the Interregnum, she and her family would sneak down to their cellar every 29th May – the birthday of her future lover, Charles II – and, submerged in total darkness, would drink a secret toast to the young man they regarded as their rightful king. Their loyalty paid off, and by the time Charles triumphantly entered London as king in May 1660 they were already lovers, having met during Charles' exile in The Hague.

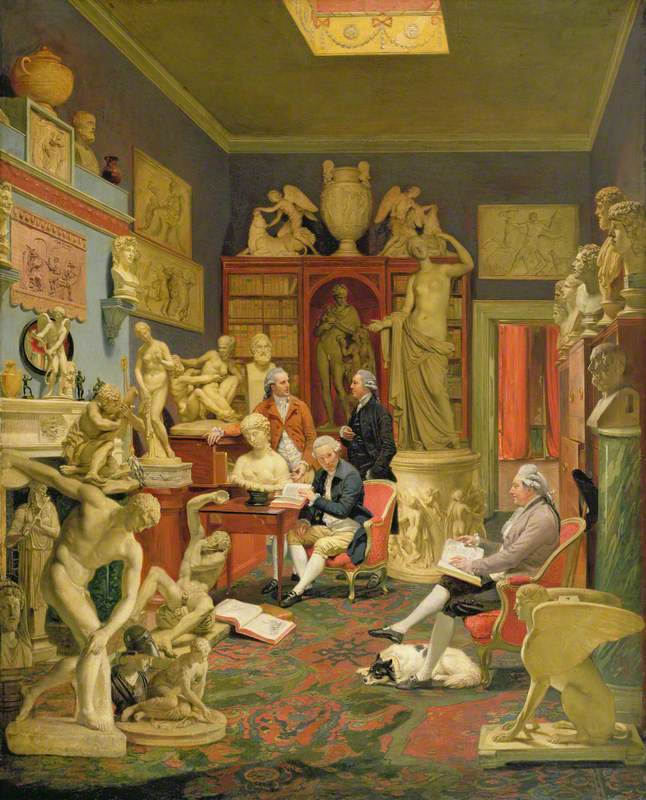

The Arrival of Charles II at The Hague, 15 May 1660

1738

Johann Baptiste Bouttats (c.1680–1743)

Barbara was already married when she became Charles' mistress, to Roger Palmer, a Catholic aristocrat who would later be made Earl of Castlemaine because of Barbara's 'service' to the Crown. Barbara's beauty made her an alluring prospect – the danger of which was clearly foreseen by Roger's father, who predicted that Barbara would make his son the unhappiest man in the world. This beauty is readily apparent from the many portraits that exist of Barbara from around this time, showing a woman with flowing chestnut hair, and wide almond eyes.

Called 'Barbara Villiers (1640–1709), Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland'

Peter Lely (1618–1680) (style of)

Many of these portraits show her resting one of her hands at the top of her cheek, undoubtedly to draw attention to those aforementioned striking eyes.

Barbara Villiers (1640–1709), Duchess of Cleveland

late 17th C

Peter Lely (1618–1680) (after)

In fact, many of the women painted by noted court painter Sir Peter Lely have this sort of look about them – his work was generally considered by contemporaries to both flatter his sitter, and to also not be entirely accurate in regards to their specific features, and this was largely because Barbara was his artistic ideal. As a result, in almost all his portraits of women, he seems to have imbued them with something of Barbara's alluring looks.

Barbara Villiers (1640–1709), Duchess of Cleveland

Peter Lely (1618–1680) (after)

So many of these similar portraits of Barbara, and their various reproductions, survive in part because owning a portrait of her became extremely popular in Restoration Britain. Interestingly, around the same time, this also became true of portraits of another future mistress of Charles II, Hortense Mancini.

To display a portrait of one of these women in mid-seventeenth-century Europe was the height of fashion. Various other portraits also give us an insight into her position and character.

In this example after Lely, the original of which is in the North Carolina Museum of Art, she is shown richly outfitted, and positively laden with pearls – in her hair, on her shoulders, at her chest, around her neck, with her hand raised delicately up to her wrist, highlighting an expensive bracelet. She haughtily stares out directly at the viewer, as if appraising us and finding us lacking compared to the general splendour of her accessories, her position, and her general allure.

Barbara Palmer, née Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland

1670

John Michael Wright (1617–1694)

Works depicting Barbara also participate in a number of trends of Restoration portraiture, she is twice seen as a shepherdess.

This was a particular favourite of contemporary court ladies and was also portrayed by Charles II's wife, Catherine of Braganza.

Catherine of Braganza (1638–1705), Queen Consort of Charles II

Jacob Huysmans (c.1633–1696) (after)

Barbara was also depicted as various saints – including her namesake Saint Barbara and Saint Catherine of Alexandria.

Barbara Palmer, née Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland

(copy after an original of c.1666)

Peter Lely (1618–1680) (copy after)

She was also painted as the Virgin Mary, with her eldest son by Charles in the role of the Christ child.

This was quite a bold move for the time – or indeed any time – for the king's mistress and his illegitimate child to be depicted as the most holy figures in Christendom. Barbara is also seen with another of her children by Charles, his favourite daughter Charlotte (later Lady Lichfield) in several portraits.

Charlotte FitzRoy (1664–1718), Countess of Lichfield

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

These works, however, seem to largely be reproductions of earlier paintings to which Charlotte has been added.

This portrait by Lely, for example, is basically identical to this portrait of Barbara alone, with the only real change being the addition of Charlotte.

Barbara Villiers (1640–1709), Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland

Peter Lely (1618–1680) (studio of)

This is also the case with this portrait by Henri Gascars, which sees a later version replace the flowers Barbara is holding with little Charlotte.

Barbara Villiers (1640–1709), Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland

Henri Gascar (1634–1701)

In total, Barbara had six children during her affair with Charles – Anne (who, legend has it, was conceived the night of Charles' coronation), Charles, Henry, Charlotte, George, and Barbara. Which of these children were actually Charles', however, is a matter of contention, as Charles and Barbara both conducted various other affairs during their relationship.

Anne is presumed to be his, but there is also the possibility of her being the child of Barbara's husband, Roger Palmer. The younger Barbara, who was born at the very tail end of Barbara and Charles' relationship, was almost certainly actually the child of John Churchill, later Duke of Marlborough, later the husband of Queen Anne's favourite, Sarah. Barbara was insistent that she was the king's – but, of course, as she would have a much higher status as the daughter of a king. Charles denied that Barbara was his daughter in private, but she bore the surname Fitzroy (meaning 'child of the king') like the rest of her siblings, and Charles made no public repudiation of her.

An odd phenomenon with Barbara and Charles' children is that they had a habit of having affairs with their parents' lovers. Anne had a very intense affair with the previously mentioned Hortense Mancini, her father's mistress, as well as her mother's lover Ralph Montagu. Charles' son by an earlier mistress, the Duke of Monmouth, went on to have an affair with Barbara herself. The younger Barbara also went on to cause scandal by bearing an illegitimate child by the Earl of Arran, and then running away to France to become a nun.

In 1670, Barbara was made the Duchess of Cleveland and Countess of Castlemaine in her own right. While some took this as a signal that she was still high in Charles' favour, it turned out to be more of a parting gift, and their relationship began to taper off around this time. Charles II also gifted Barbara Nonsuch Palace in Cheam, an extravagant building originally commissioned by Henry VIII. However, Barbara had it torn down in 1682, in order to pay off her gambling debts.

The end of their affair did not, however, mean that Barbara was no longer in Charles' life. John Evelyn recorded that only six days before his death in February 1685, the king had been playing cards with Louise de Kérouaille (who had usurped Barbara as the king's main mistress), Hortense Mancini (who went on to briefly, in turn, usurp Louise as the king's main mistress), and Barbara.

Barbara would go on to outlive Charles by 24 years, and managed to fit plenty more scandal and drama into that time. The year of the king's death, she embarked upon an affair with an actor of such a bad reputation that he would go on to be nicknamed 'Scum', and gave birth to his illegitimate son (whose name seems to be unrecorded by history and thus probably died in infancy). She then began an affair with Robert Fielding, a womanising minor aristocrat, around 1698, and (after the death of Roger Palmer in 1705) married him.

It was during her brief widowhood that this painting of Barbara by Sir Godfrey Kneller was painted.

Barbara Palmer, née Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland

(copy after an original of c.1705)

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) (copy after)

While her hand still rests against her cheek, like in so many of her youthful portraits, this is a woman who looks rather more subdued – less haughty and grand, the shining star of the court, and more a refined older lady in widow's weeds.

But the drama of Barbara's life wasn't over yet. Her marriage to Fielding turned out to be an unmitigated disaster. It turned out that Fielding had begun courting a wealthy heiress named Anne Deleau; around the same time that he had first started courting Barbara. Unbeknownst to Barbara, he had actually gone on to marry said heiress only 15 days before he wed Barbara, making his and Barbara's marriage bigamous.

However, even more dramatically, Fielding had been hoodwinked – the woman he had married was not Anne Deleau, but a friend of Deleau's maid disguised as Deleau. Fielding had bribed this maid into helping him get Anne Deleau to accept his proposal. The maid, however, knowing that her mistress seemed unlikely to accept but wanting to receive the bribes, concocted the whole deception. To make matters worse, Fielding started an affair with Barbara's granddaughter by her daughter Charlotte (they perhaps even had an illegitimate child together), also named Charlotte, and began to treat Barbara herself so cruelly that she had to get an order of protection out on him. Only a year after this ill-fated marriage began, Barbara was successful in having it annulled on the grounds of bigamy.

Barbara Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland

Peter Lely (1618–1680) (after)

Barbara lived just three more years, dying in October 1709, aged 68. Let us hope in those final years, she finally got some rest – she certainly lived through enough scandal and drama for several lifetimes.

Chloe Esslemont, freelance writer and co-founder of TabloidArtHistory