It took more than a year for my Dad to recover from a severely broken ankle after his leg got caught between the rungs of a ladder. Here, an innocuous domestic object momentarily became an instrument of torture. Before his crash landing came a fall: a reminder of the ladder's association with balance, precarity and instability.

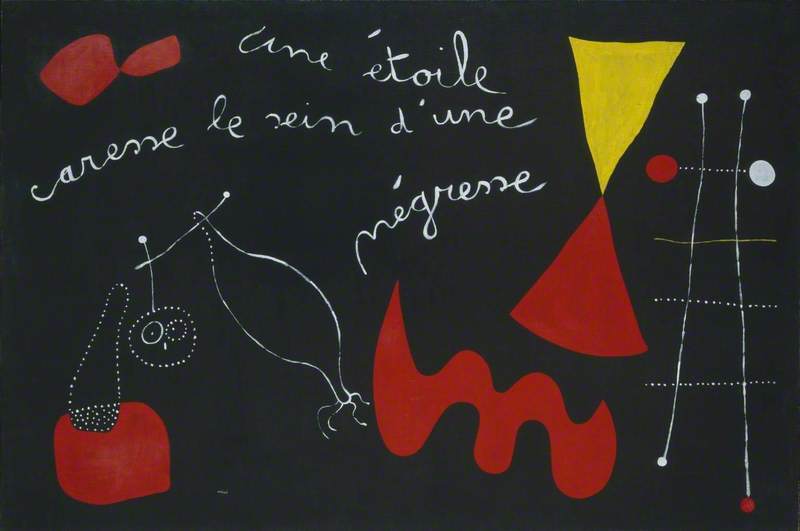

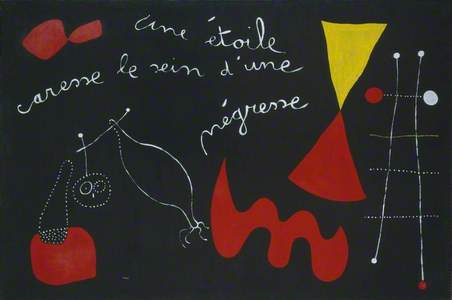

Ladders appear frequently in art. Although a practical object – used to fix roofs or pick fruit – they're also useful metaphors for aiming higher, for progress, or for ascension to worlds elsewhere. Joan Miró incorporated ladders into his Surrealist works throughout his career, often highlighting their celestial aspect – their capacity to bring us closer to the stars.

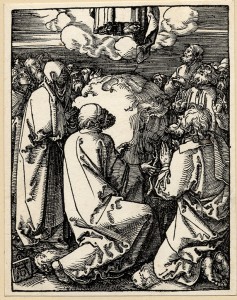

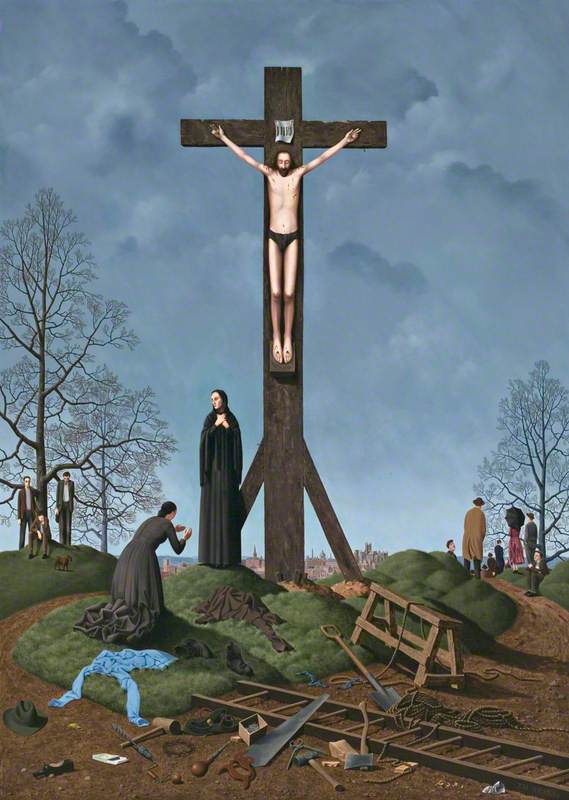

A more obvious relationship between the ladder and heaven can be found in Christian art, particularly in images of the Crucifixion. In the thirteenth century, Passion images emerged showing Christ willingly climbing a ladder to reach the cross in an act of bravery; elsewhere, Christ is shown already on the cross, beside two ladders, as in Rembrandt's Lamentation. In such depictions, the ladder is representative of Jesus's role as mediator between God and man.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ about 1635

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

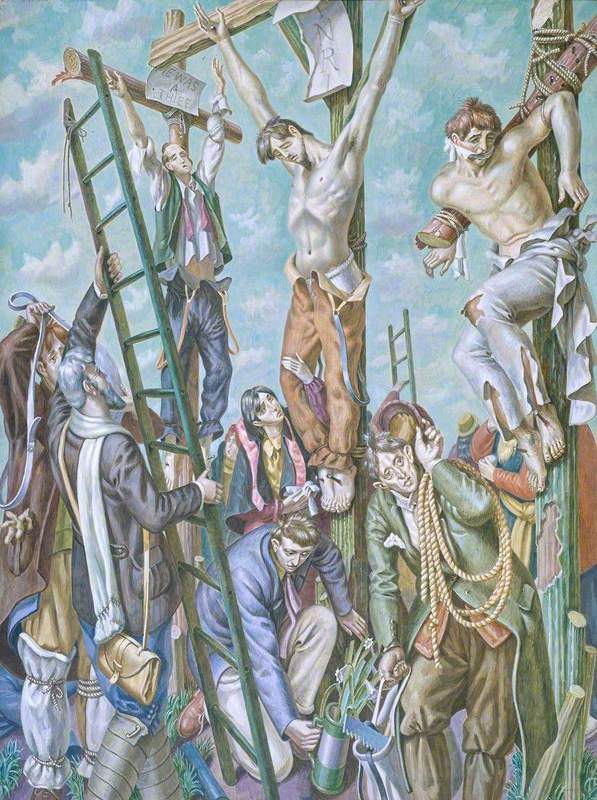

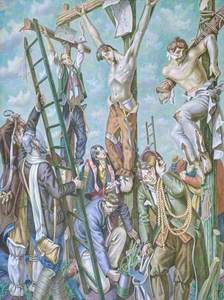

The National Gallery, LondonImages of the Crucifixion by modern British artists such as Michael Rothenstein and Stanley Spencer draw on this motif to make a point about war and contemporary human suffering. Rothenstein's The Crucifixion (1937) similarly features two ladders, this time alongside three men tied to crosses. Rothenstein, who was Jewish, points to the persecution of Jews by the Nazi regime, suggesting a continuous line of cruelty and intolerance.

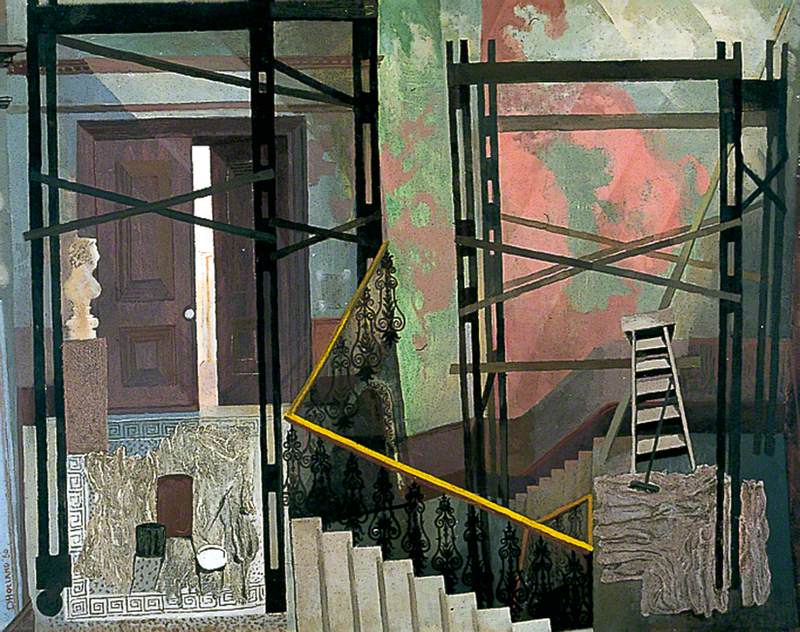

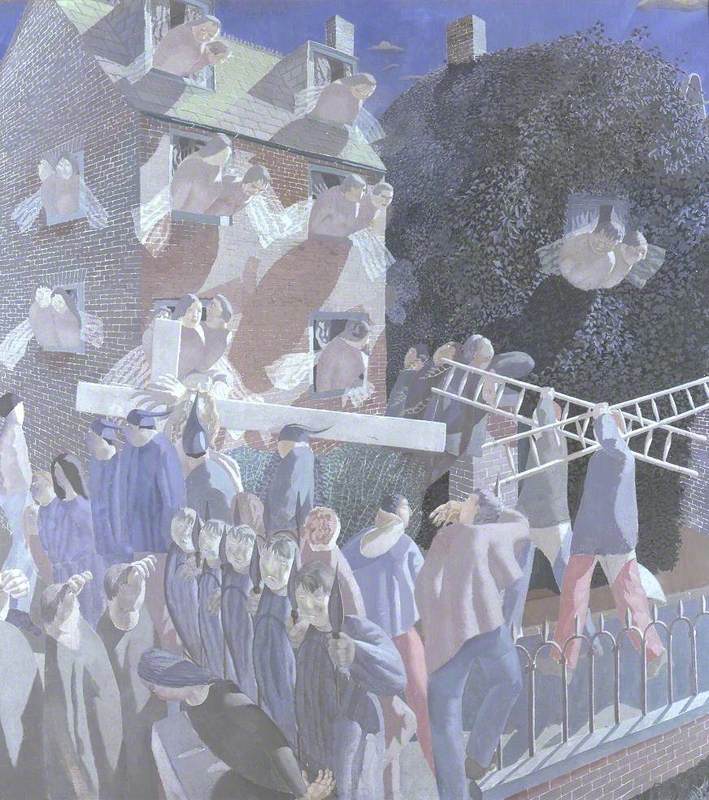

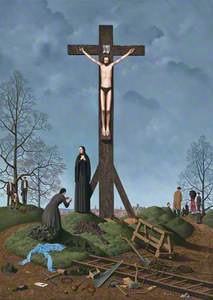

As Christ carries the cross in the middle of Spencer's 1920 work, two ladders criss-cross behind him; the angels above and people below seem to also divide the canvas into earthly and heavenly realms. In Tristram Paul Hillier's 1954 version, an abandoned ladder lies discarded on the floor, its work as an aid in tying Christ to the cross now over. A sign, perhaps, of religion's role in a broken, post-war world?

© the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary Art

Tristram Paul Hillier (1905–1983)

The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary ArtAnother Biblical theme that has been taken up by artists is the story of Jacob's Ladder, from Genesis. This refers to Jacob's prophetic dream about a ladder or stairway leading up from earth to heaven, surrounded by angels. Often read as a sign of God's promise to Jacob, that he is chosen as leader of the Israelites, the dream also suggests the intimate connection between God and man. This human link to the divine is clear in Nina Grey's sculptural interpretation, which shows Jacob asleep at the base, from which emerges a tower of angels.

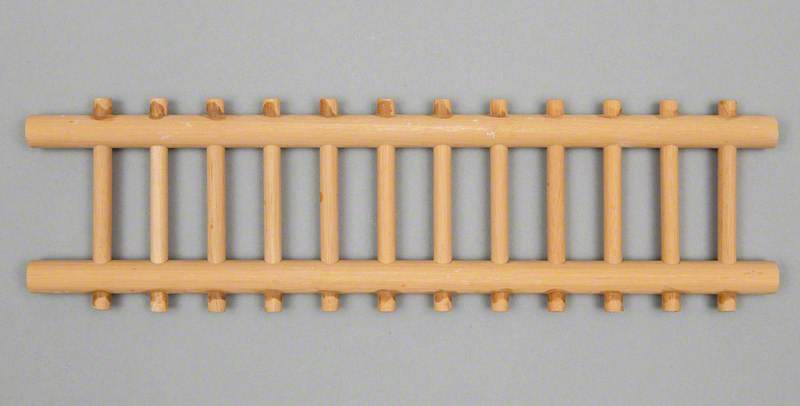

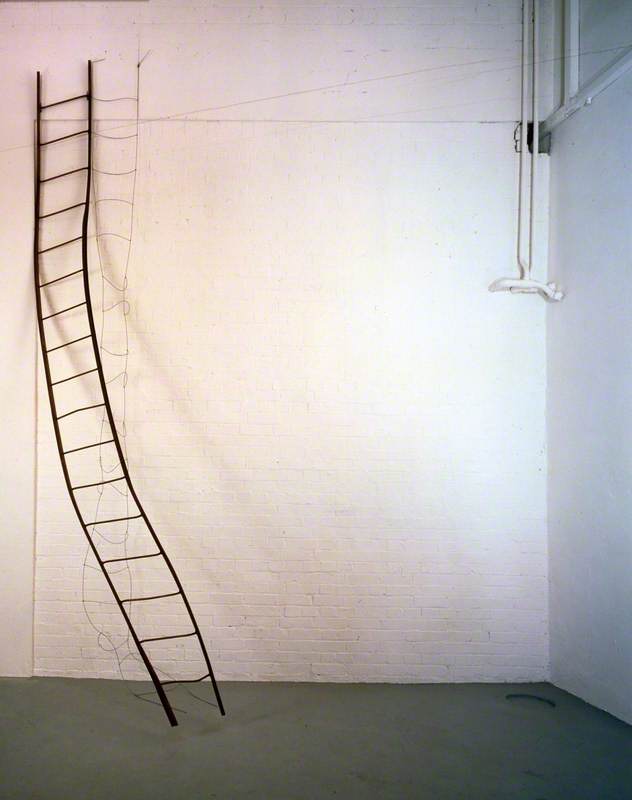

The ladder has in fact proved a popular medium for sculptors, not least because of its minimal, grid-like form which also offers the chance for playful manipulation. In Richard Wentworth's 35°9, 32°18 from 1985 – the title is a map reference which precisely locates the coordinates of Jacob's dream in Israel – the steel ladder appears wobbly, its unsteadiness made worse by a ghostly cable ladder hanging loosely behind.

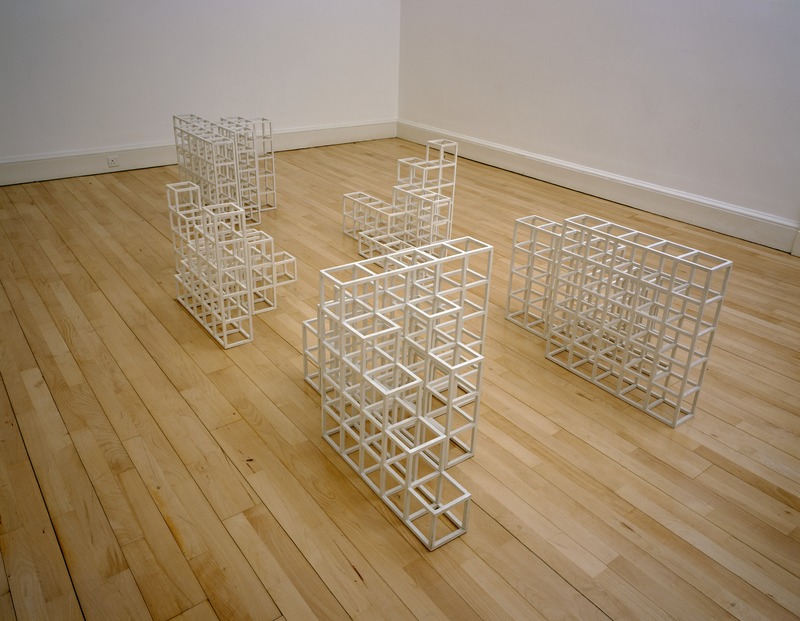

The geometric forms of many minimalist sculptors, such as Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre, often conjure the idea of ladders – hollowed space interrupted by flat planes.

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2025. Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Five Modular Structures (Sequential Permutations on the Number Five) 1972

Sol LeWitt (1928–2007)

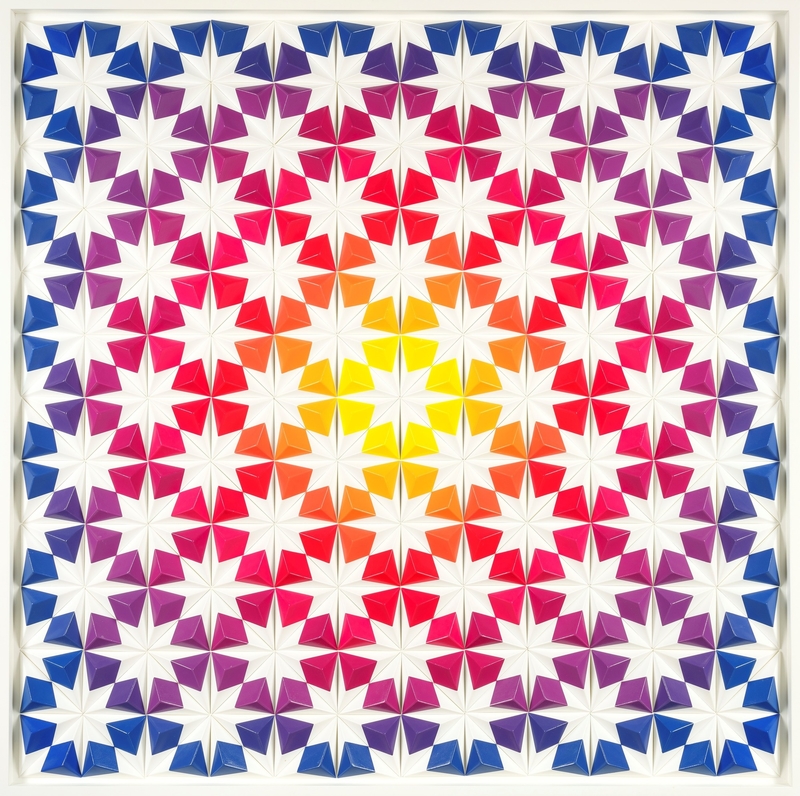

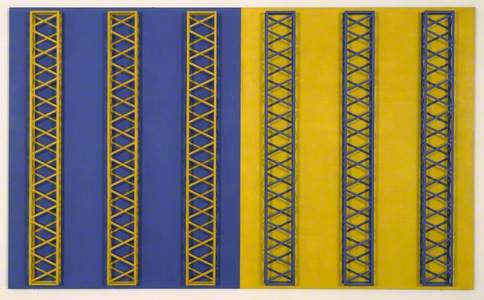

National Galleries of ScotlandThe lattice construction of 3Y + 3B by British-Pakistani artist Rasheed Araeen, an artist associated with British minimalism, echoes the cubist towers of LeWitt's Five Modular Structures (1972). The effect of criss-crossing lines, which look like wonky ladder rungs, comes from the work's sculptural nature, which is made up of three-dimensional, cube-like structures screwed onto hardboard. The work nods to Araeen's background in engineering as well as the decorative patterns found in Islamic art.

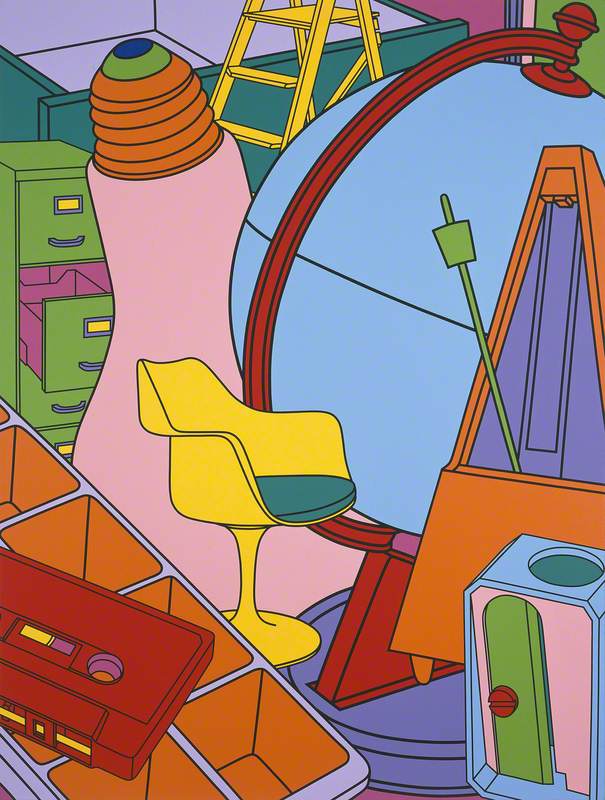

The suggestion of ladders is everywhere in the work of Joe Tilson, even in the 'Ziggurat' series of stepped pyramid works – a reference to ancient architecture – which he began in 1963.

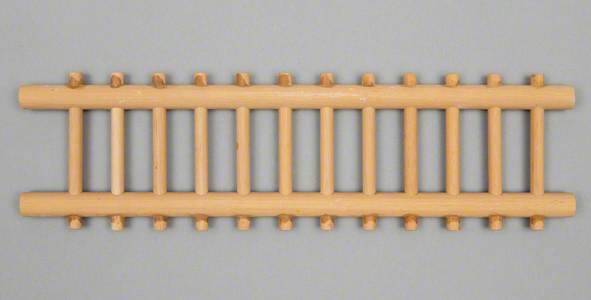

When he more fully embraced a mystical approach to art in the 1970s, prompted by a move to the countryside, Tilson began a body of work known as 'Alchera', named after the ancient aboriginal concept of 'Dreamtime'. Tilson drew on his initial training as a carpenter and joiner to explore natural materials and ecological themes, creating works full of symbolic imagery. Fire Ladder, Air Ladder, Water Ladder, Earth Ladder (1974) points to his interest in the four elements, the ladder form perhaps an attempt to impose order on the elemental, or that which is just out-of-reach.

© DACS 2025. Image credit: Royal Academy of Arts

Fire Ladder, Air Ladder, Water Ladder, Earth Ladder 1974

Joe Tilson (1928–2023)

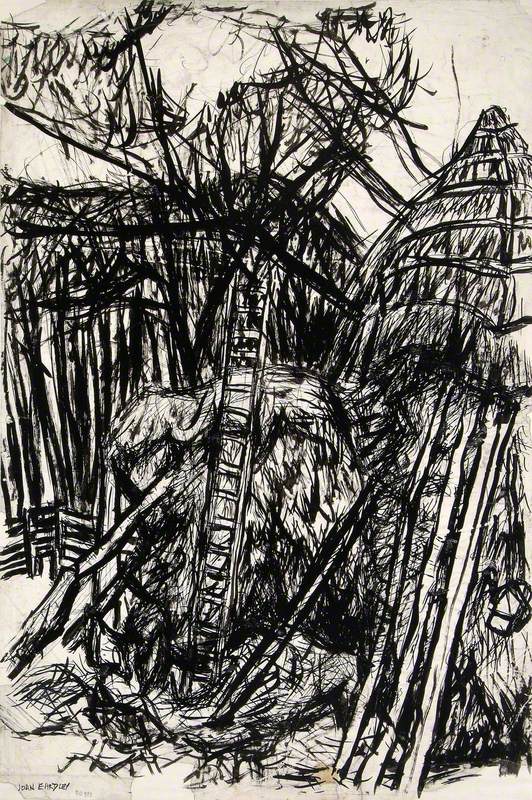

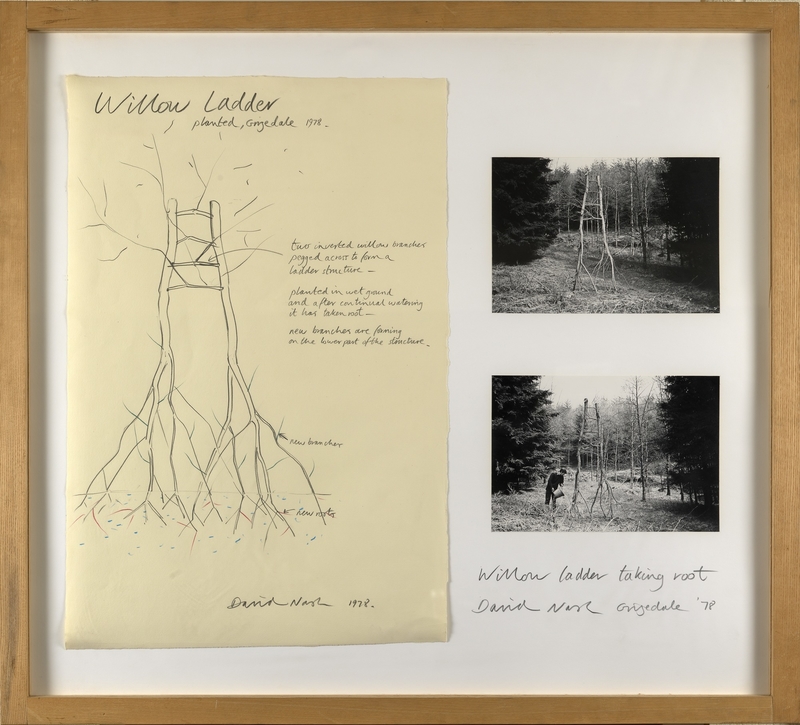

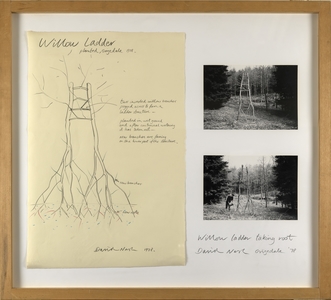

Royal Academy of ArtsWelsh artist David Nash also finds inspiration in the natural world, working especially with wood and trees. His interest in ladders began in 1978 while on residency in Grizedale Forest, Cumbria. This drawing records Nash's attempt to plant two willow branches in the hope they would take root and form a new, ladder-like structure.

Seen front-on, his Ladder, from the same year, looks balanced despite its slight curve, yet a side view shows it is held upright by two back legs – a reminder that it is a useless object unless supported. Yet Nash is perhaps less interested in the functionality of this object, instead intrigued by the capacity of a tree to regrow – as his drawing above also reveals – and of nature's continuity.

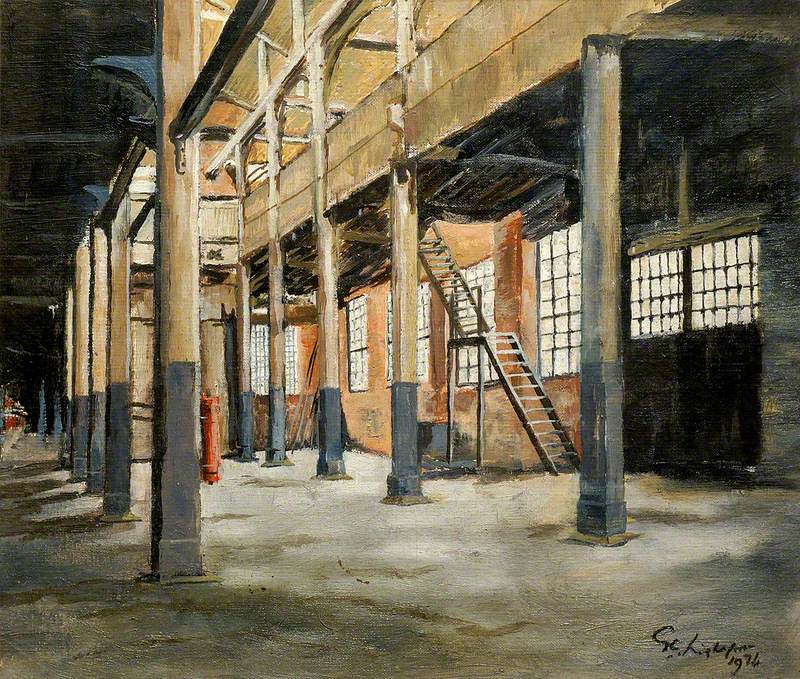

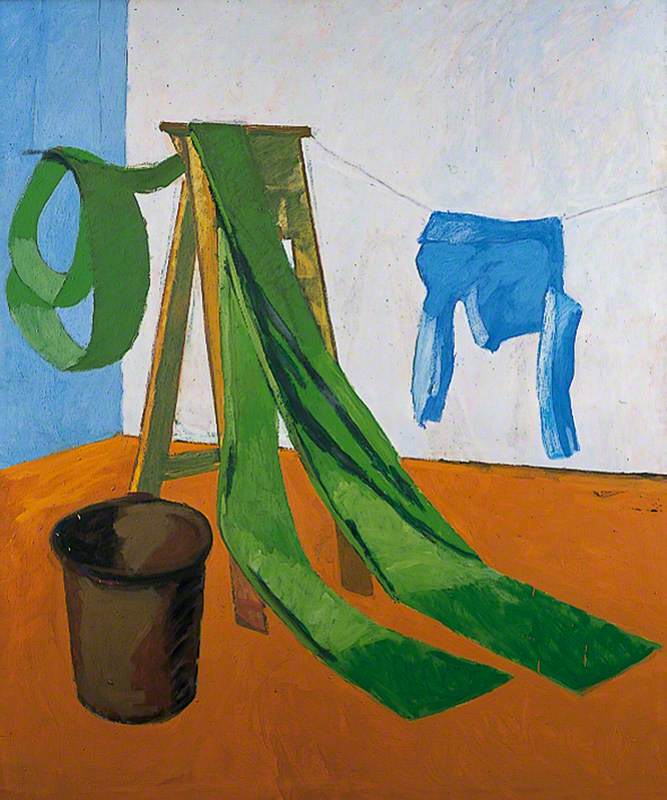

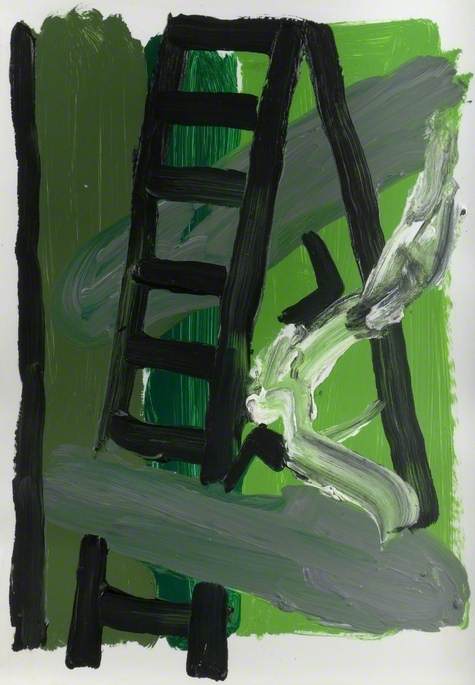

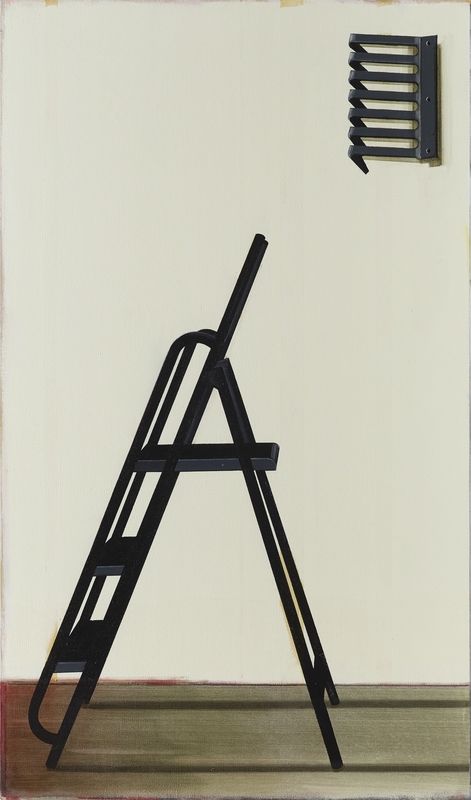

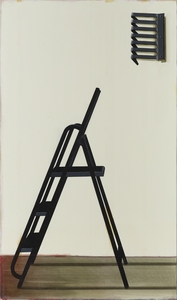

Ladders can also be found in other modern paintings – sometimes obviously, as in Victor Willing's Painting with Stepladder (1976), a scene which unites disparate objects to suggest a pause in action, or Bruce McLean's Pipe Smoke and Step Ladder (1984). Against an abstract background of thick brushstrokes and squiggles of paint, the black lines of the figurative ladder stand boldly out. It's worth noting that the step ladder is often found in artists' studios, a practical tool used to aid the creative process.

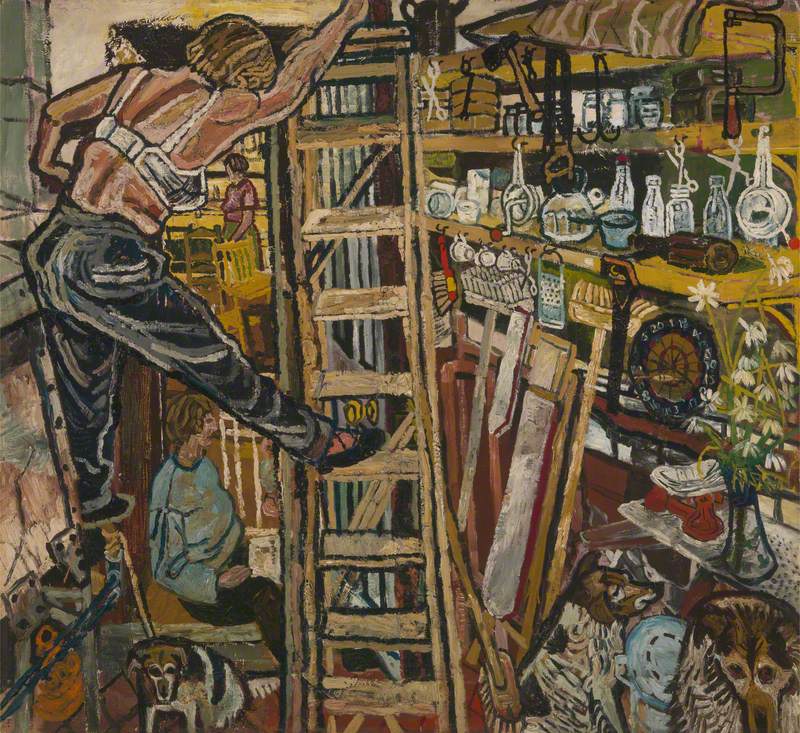

John Bratby's self-explanatory Jean on a Step-Ladder in the Kitchen (1956) is indicative of his 'kitchen-sink' approach, in which the grittiness of everyday life in post-war Britain is rendered in minute detail; nothing is off limits. Here, though, the central ladder, which dominates the cluttered composition, gives this work a surreal quality, a shirtless Jean hanging from it like an acrobat at the circus.

Duncan Grant's Still Life with Jug (1912) hints at a ladder, and while not wholly visible, it nevertheless threatens to knock over the jug and strategically balanced fruit. But look again, and perhaps Grant has caught the moment just before the fall; the barrel seems to tilt, the whole composition slightly off-kilter.

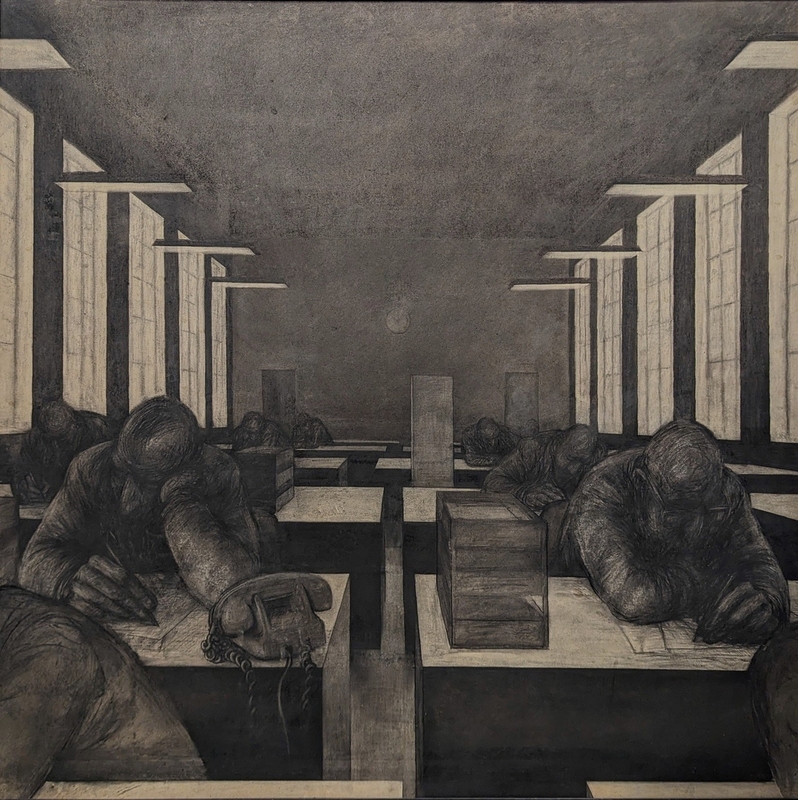

Leper Squint No. 3 (2012) by Michael Simpson more clearly references the ladder's otherworldly associations. Simpson is interested in religious history, and this painting is part of a series looking at leper squints, an architectural feature of medieval churches consisting of a small window set in a church wall which allowed lepers to attend mass without the threat of contamination.

In this representational painting, the ladder acts as a bridge between the physical world and spiritual salvation. Yet while this object might allow the excluded to feel included, Simpson's painting – and indeed, his wider series – suggests solitariness and hints at heaven as an unreachable goal.

For Yinka Shonibare, however, the ladder is more clearly a symbol of attainment. His Magic Ladders series, commissioned by the Barnes Foundation in 2013, considers the wonder of childhood learning, enlightenment and the opportunities that come from education – not least, the ability to endlessly rise and progress.

View this post on Instagram

But the simple geometric form of the ladder, and the object's ability to conjure both absence and presence, lends itself well to the pared-down qualities of abstract painting. Lauren Iredale's Untitled from 2010 features thin blue and yellow lines against a vivid red background: a meditative examination of form and colour perhaps, but also, the rungs of a ladder.

The stepped columns in Robert Anthony Collinge's abstract Grey and Brown III (1965) similarly suggest a ladder through the interplay of light and dark.

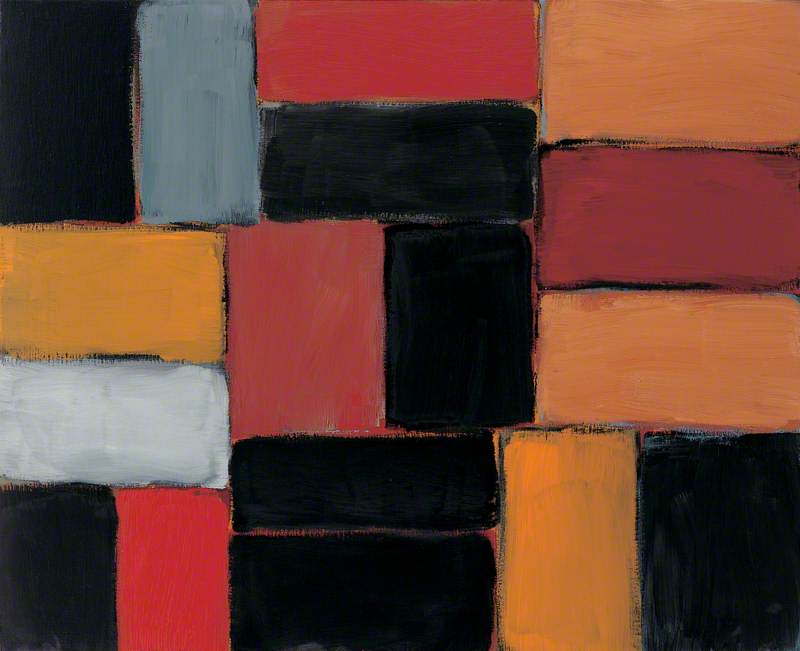

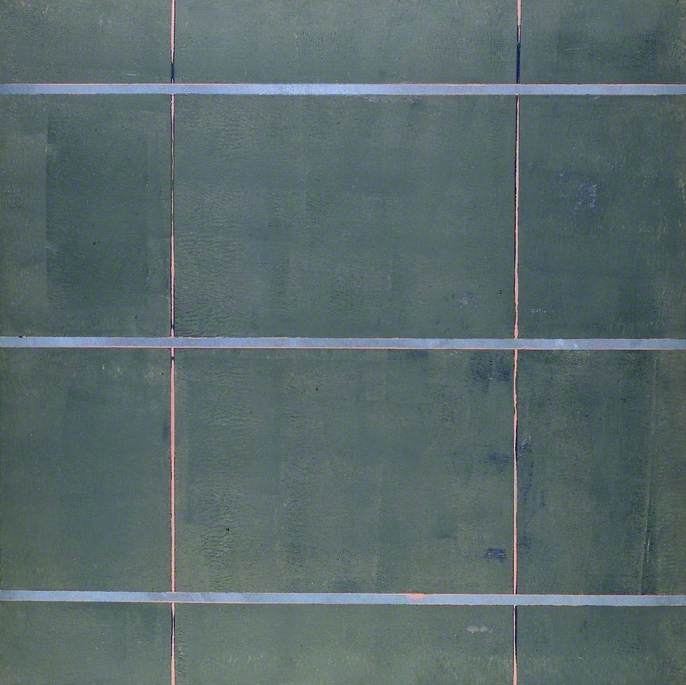

This painting calls to mind the work of Sean Scully, who has been candid about the influence on his canvases made up of vertical and horizontal bands: 'In many of my paintings there is a ladder-like motif', he told Wallpaper in 2022. Even in early works, such as the more linear, gridded Painting 20/7/74, No. 3/3 from 1974, this statement rings true.

Scully's work once again returns us to the idea of the ladder as a mediator between the physical and spiritual realms. In 2019, for an exhibition at the San Maggiore church as part of the Venice Biennale, he made a ten-metre-high stacked sculpture called Opulent Ascension, inspired by Jacob's dream of a ladder heavenward – its colourful, ladder-like bands at odds with the architecture's austere stone walls.

View this post on Instagram

In an interview with Art UK in 2020, Scully talked about the work as a 'spiritual metaphor', ascending elsewhere. Perhaps the ladder is an artistic metaphor too, enabling us to access a rich imaginative world just out of sight.

Imelda Barnard, Commissioning Editor, modern and contemporary British art at Art UK

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation