Visitors walking into The National Gallery's exhibition 'Australia's Impressionists' might be forgiven for thinking they have taken a wrong turn into an exhibition on a different subject altogether. After all, the first painting in the exhibition, Tom Roberts' Fog, Thames Embankment, was painted almost as far away from Australia as it is possible to get, in its near-antipode, London.

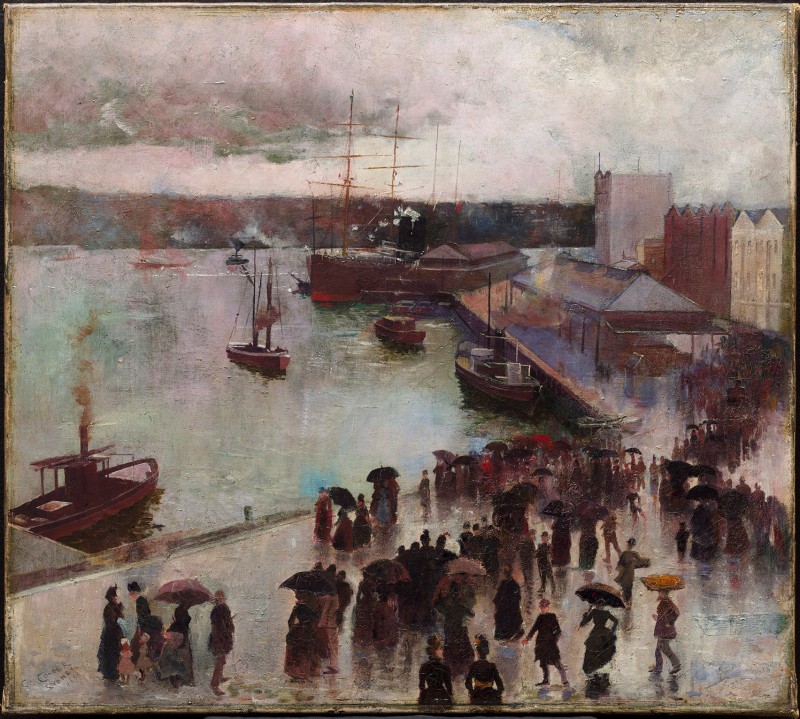

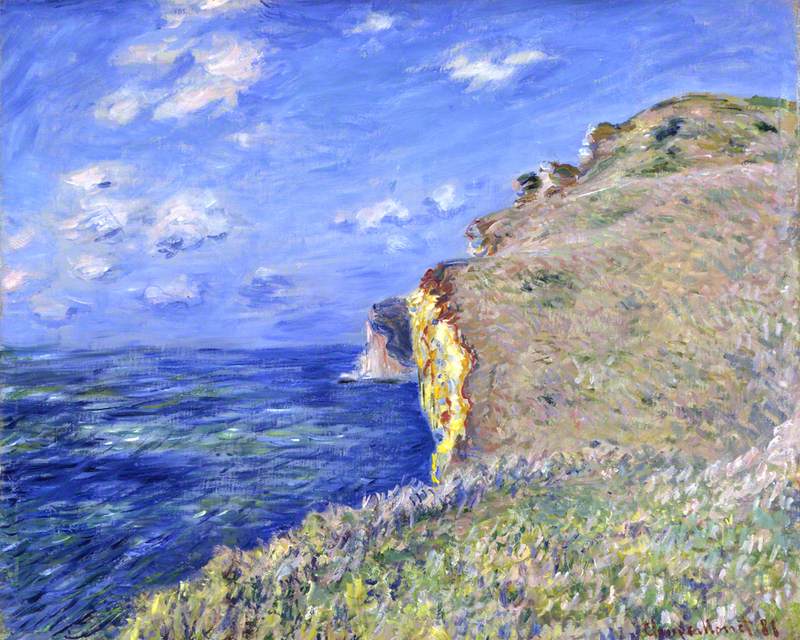

Of the other pictures on display in this first room, the majority are not only urban subjects, but grey and rainy at that – a far cry from the outback stereotype. Nor do the paintings, on first glance, look much like 'Impressionism' – or at least they don't have much of the broken brushstrokes and high-keyed colour of French Impressionists such as Monet and Pissarro that is now most widely associated with the term.

Fog, Thames Embankment

1884, oil on paperboard by Tom Roberts (1856–1931)

Yet these apparent incongruities are precisely what make examining the work of Australian Impressionist painters so fascinating, and so instructive. Impressionism was in fact a broad church, encompassing a whole range of styles loosely united by an interest in painting directly in front of their subject, often en plein air, and in depicting modern life. The French Impressionists were the most famous in an international network of artists exploring this new approach to painting, seeking to break free from academic convention.

This is the first exhibition in the UK dedicated specifically to the work of Australian Impressionist painters. It showcases four of the most prominent: alongside Roberts (1856–1931), the painters Arthur Streeton (1867–1943), Charles Conder (1868–1909) and John Russell (1858–1930). They are inevitably but four among many others, though together they provide an important introduction to the subject for an audience largely unfamiliar with it.

Roberts, Streeton, Conder and Russell were themselves no strangers to London. They all lived in the city for different periods in their artistic careers, and would have known the National Gallery and its collection well. Roberts' silvery view of the base of Nelson's column looking down Whitehall from the north terrace of Trafalgar Square might easily have been painted in between sessions copying the Spanish masters in the Gallery behind him.

Trafalgar Square

1904, oil on cardboard by Tom Roberts (1856–1931)

Staging an exhibition on Australian Impressionist painting at The National Gallery therefore has particular resonance for both the history of Australian Impressionism, and for that of the Gallery, which from its inception has always been an important destination for practising artists. The exhibition takes its place within a broadening of the Gallery's mandate in recent years to explore painting in the Western tradition beyond the geographic boundaries of Western Europe itself. When Streeton's Blue Pacific arrived on loan in September 2015 it was the first Australian painting to hang in The National Gallery, and in turn prompted the exhibition which invites us to revisit to the Gallery's permanent collection with new eyes.

Blue Pacific

1890, oil on canvas by Arthur Streeton (1867–1943)

Roberts had come to London from Melbourne in the early 1880s to study at the Royal Academy Schools. It was however less the tuition and much more his exposure to the local avant-garde that would prove the most formative lesson Roberts would pick up in the imperial capital. Fog, Thames Embankment shows a view also painted by Monet (see below), but displays a particular debt to Whistler, whose exhibition of similarly small-scale, atmospheric works, Notes – Harmonies – Nocturnes Roberts surely saw in London in 1884, the same year he painted this small panel. Streeton later reflected that Roberts' views of the Thames such as this had elicited an 'exciting revelation' among Australian painters when he brought them back with him in 1885.

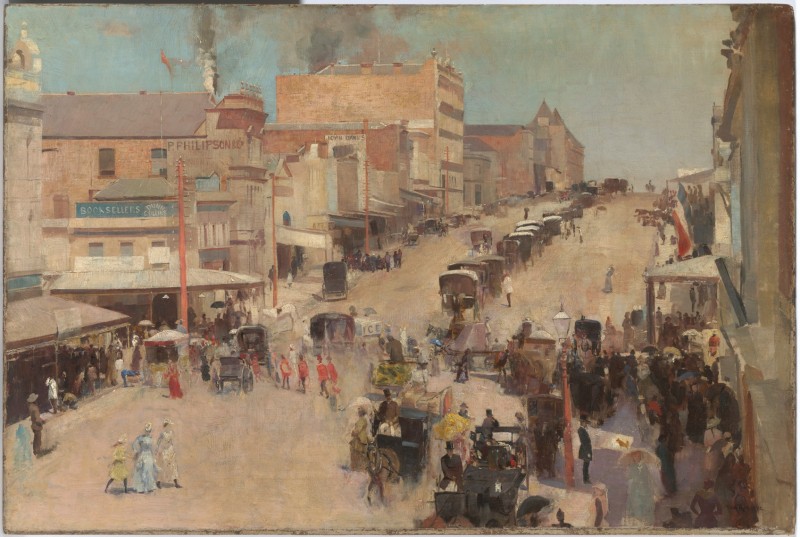

The first section of the exhibition introduces the Australia to which Roberts returned: already one of the most highly urbanised societies in the world, with Melbourne fast becoming the second largest city in the British Empire and one of the richest in the world. It was here that in 1889 Roberts, Streeton and Conder staged the '9 by 5 Impression Exhibition', so called because many of the approximately 180 'impressions' were painted on cigar box panels of roughly 9 x 5 inches.

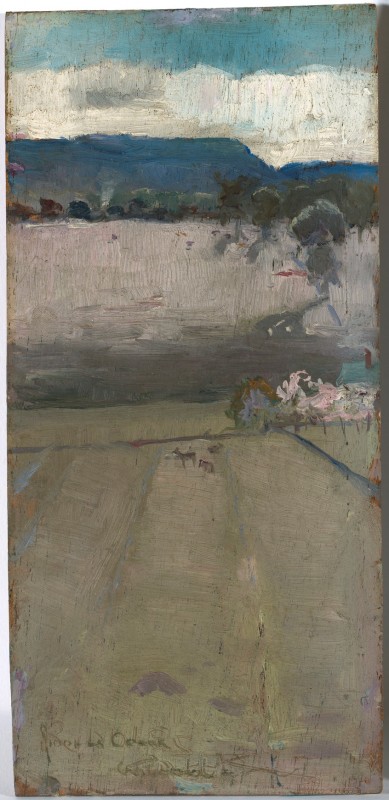

While they no doubt had the artist-led French Impressionist exhibitions in mind, the aesthetic pursued took its cue much more overtly from Whistler, right down to the bold, wide timber frames, sometimes embellished with metallic paint, as in Conder's Dandenongs from Heidelberg. Intended to provoke (but also to be marketable to a wealthy, sophisticated clientele), the exhibition made a bold statement about where these artists saw the future of painting in Australia.

Dandenongs from Heidelberg

c.1889, oil on wood panel by Charles Conder (1868–1909)

This was a point of much discussion at the time, as the various colonies on the Australian continent moved towards Federation and the formation, in 1901, of 'Australia' as a nation. The second section of the exhibition explores the role Australian Impressionism played in forging a distinctly 'Australian' identity during these years – one much closer to certain stereotypes about the Australian landscape than the urban scenes in the first section, but which in fact concealed as much of the colonial reality as they revealed.

Plein-air painting at times assumed a monumental scale, taking on a status of history painting in works such as Streeton's audacious Fire's On. Depicting the death of a worker at the site of a railway tunnel being blasted through the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, the canvas itself bears the scars of the lethal explosion, having been patched up after a being pierced by flying rock.

Fire’s On

1891, oil on canvas by Arthur Streeton (1867–1943)

Here, as in Roberts' dramatic scene of thirsty sheep stampeding towards a muddy waterhole in A Break Away!, 'authentic' Australian identity was cast in the figure of the male settler, resilient in the face of a formidable and unforgiving landscape. While this image of Australian identity appealed to a largely urban-dwelling population, it lent a sense of nostalgia to recent colonial history that obscured more than 50,000 years of Indigenous cultures so violently disrupted.

A Break Away!

1891, oil on canvas by Tom Roberts (1856–1931)

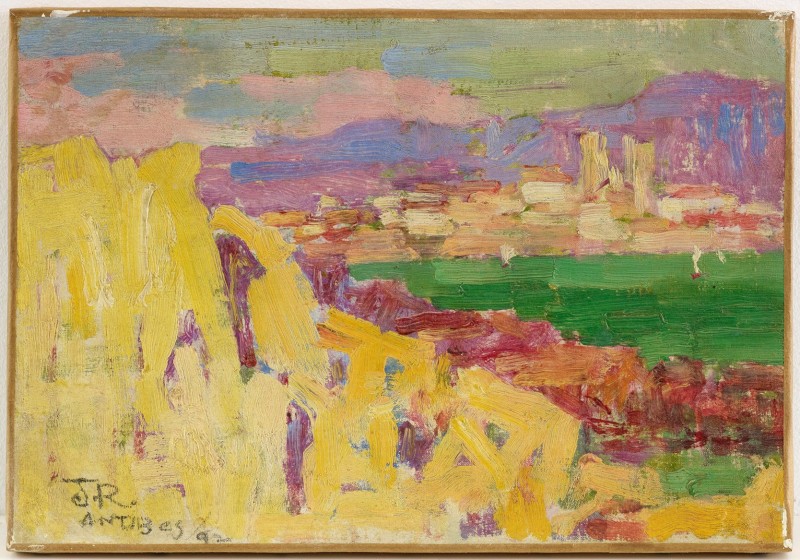

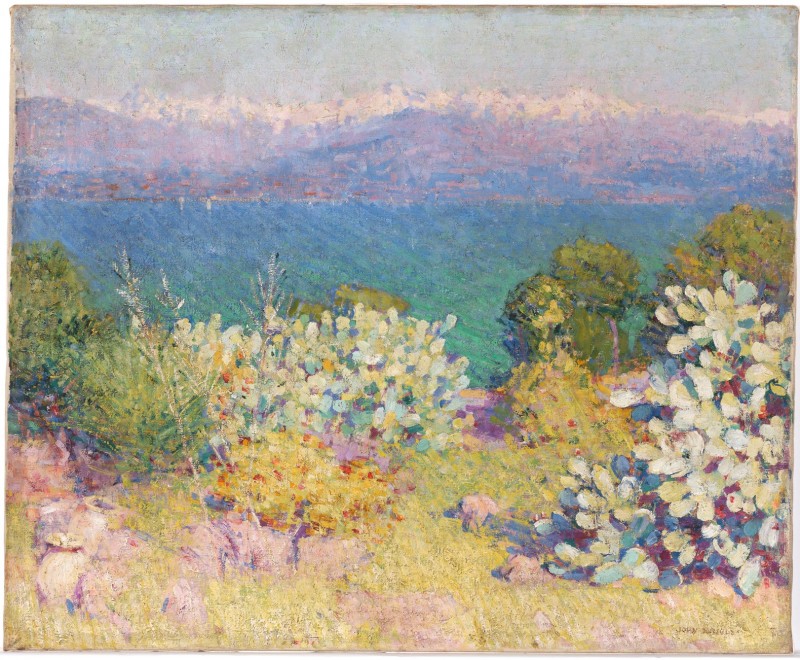

The final section presents something of a mini-monographic exhibition within an exhibition, focusing on Russell. Although he was born and died in Sydney, Russell spent the majority of his artistic career in Europe, closely connected to the avant-garde. Long regarded merely as a footnote in the history of French Impressionism, and until relatively recently largely excluded from histories of Australian painting, Russell is presented here as an important part of both narratives.

Painting in a manner much closer to French Impressionism than the other artists in this exhibition, and frequently writing to Roberts, whom he had befriended while a student in London, to keep him abreast of the latest developments in French avant-garde painting, Russell invites fascinating questions about what it meant to be an 'Australian Impressionist'.

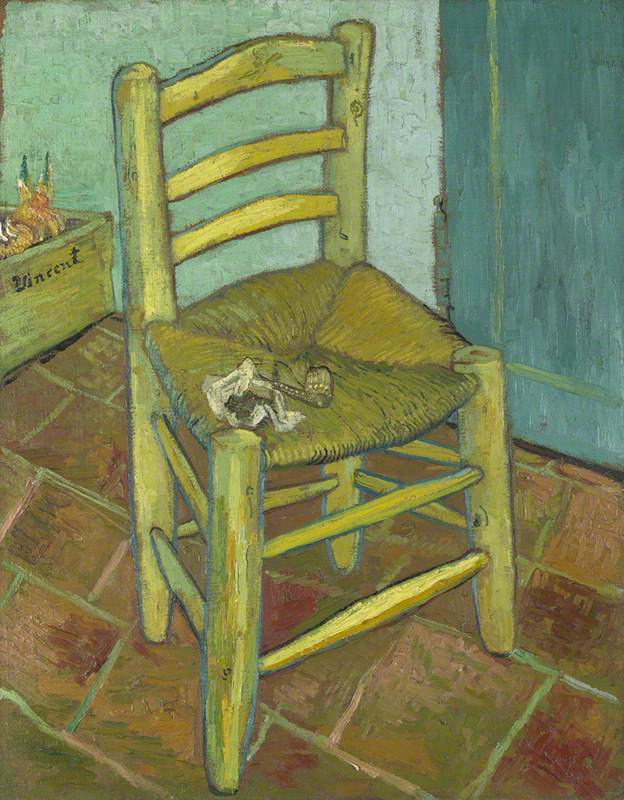

Russell's work records the manifold influences of and affinities with his friends and contemporaries – Van Gogh and Monet, as well as Gauguin – but is distinguished first and foremost by his achievements as a colourist, which in turn had a transformative influence on the work of the young Matisse. He plays an important role in the exhibition in both highlighting, by contrast, the singularity of Impressionism as it manifested itself in Australia, and, conversely, underscoring the internationalism of the broader movement.

Allison Goudie, co-curator of 'Australia's Impressionists'

'Australia's Impressionists' was on at the National Gallery, London, until 26th March 2017