Art Matters is the podcast that brings together pop culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

'Tis the season for talk of witches and ghouls, though, in reality, witches have become part of our everyday pop culture all the year-round. Harry Potter alone is a multi-billion-pound franchise, endearing millions to the story of a little wizard boy and his witchy mates. Sabrina the Teenage Witch is another example – whether you like the comic, the 1990s television series or the darker Netflix reboot, it's a popular franchise centred on an age-old concept.

'There's probably not a society in the whole world which, at some stage in its history, has not believed in the power of witches as beings with special magical powers that can be used for malignant, destructive, predictive ... or even occasionally for healing purposes,' says artist, art historian and curator, Deanna Petherbridge. 'Witches are the scapegoats in a world governed by superstition.'

Though the narrative around witchcraft shifts across the centuries in Europe, one thing that remained consistent was its connection to women.

Whether your reference point is the Bible or one of Shakespeare's plays, witches are often made out to be hideous and nefarious creatures. They are largely depicted as women in art and stories, but there are cases of real men and children who were also tried and executed as witches. The idea of witchcraft has been a cause of mass panic at various points, and this combination of fear and interest created fertile ground for artists.

'Even in the Greco-Roman world, the legends about witches were sources of pottery decorations or the subject matter behind frescoes and sculptures,' says Deanna.

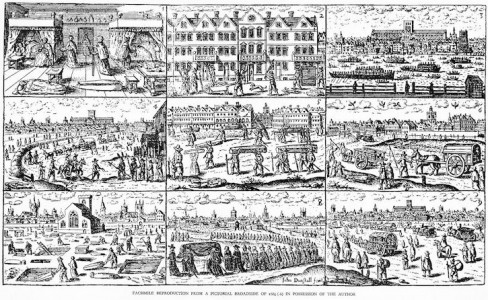

Printmaking and texts played an important role in shaping people's ideas around witchcraft, and the invention of the Gutenberg printing press meant that texts referencing witches were more easily disseminated. Books like De Lamiis et Pythonicis Mulieribus ('Of Witches and Diviner Women') in 1489 and the Malleus Maleficarum from 1487 informed the iconology of witches, and printmaking made it possible for these ideas and images to spread widely and cheaply.

A Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat, with Four Putti Carrying an Alchemist's Pot...

c.1500, engraving by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

One artist who took ideas from these texts and applied them to his work was Albrecht Dürer. His engraving produced in 1500 of a witch riding a goat – a symbol of Satan – is one of his most famous works on this subject. It captures the public's fascination with witches at the time and would go on to inform other representations of witches.

'Dürer, in a sense, and his principle pupil who was called Hans Baldung Grien ... really established this kind of iconography,' says Deanna. 'The iconography is amplified by the artists, but it does come from the texts.'

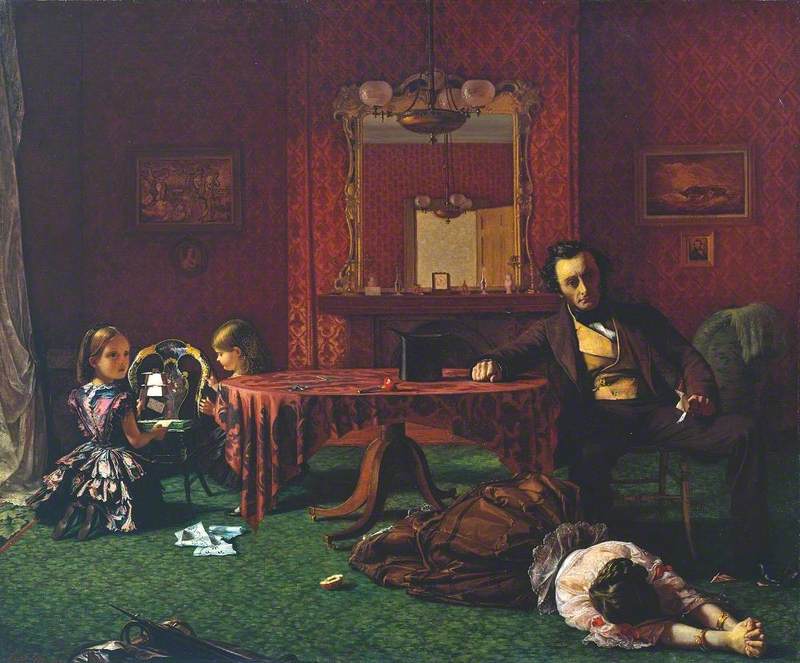

As witch trials became prevalent in the sixteenth century, ideas around witchcraft took a more serious turn that is later reflected in art. Some of the most significant paintings on the subject coincide with this period of witch-mania across Europe and can be found in UK collections. Witches at their Incantations (1646) by Salvator Rosa in The National Gallery collection is one such example.

'[Salvator Rosa] was also a poet, a playwright, he also knew all the influential people of the time,' says Deanna. 'And a lot of them at this time were as interested in witchcraft and the ideas about it as they were in other seventeenth-century matters.'

One of the last people to be convicted under the Witchcraft Act in the United Kingdom was Helen Duncan in 1944. She falsely purported herself to be a medium and was sentenced to nine months in prison under the 1735 law. There is now a bronze bust of her likeness in The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum.

Witches' Sabbath by Flemish artist Frans Francken II highlights the loose morals of witches in an almost comical fashion. The image plays up the sexuality of witches, showing some of the women partially clothed or in suggestive positions. The inclusion of little monsters and putti flying up the chimney detracts from the potential seriousness of the subject, pushing it into the ridiculous.

The Sorceress

1626, etching & engraving by Jan van de Velde II (c.1593–1641)

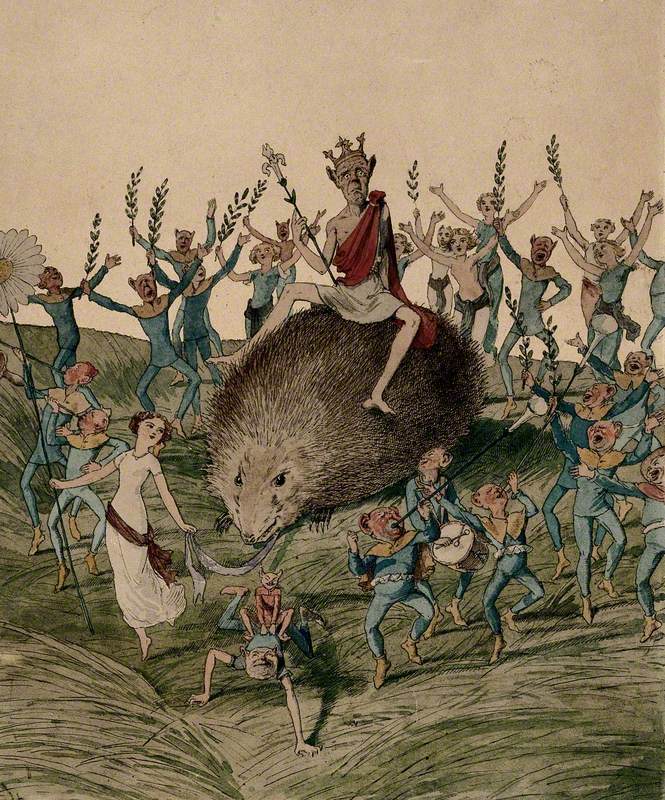

Another print around this period by Jan van de Velde II employs similar dramatic imagery of demons and chaos. 'It's about pipe-smoking. Witches have become associated now with one of the social evils of the time, which was smoking,' says Deanna. 'Witchcraft sometimes is just a factor for people to enjoy themselves – to be lewd, to be rude.'

Volaverunt (They have flown)

(from 'Los Caprichos'), 1799, etching, aquatint & burin by Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)

In the astrology episode, we discussed the impact the Age of Enlightenment on people's belief in magic and the occult. The effect was similar with witchcraft: as society moved towards ideas that could be grounded in reason, there was a decline in superstitious beliefs. This is reflected in the depiction of witches in art, and we can take Francisco Goya's 'Los Caprichos' series, which includes several images of witches, as an example.

'He's using witches as a symbol, in a way – a metaphor for corruption and dissolution, particularly of clerics,' says Deanna. 'He was absolutely obsessed with witches, but he was also a man who associated with intellectuals, with political dissidents, with all the things of an enlightened Spain – but he was also, like everybody else, still fascinated with a past that hadn't been completely put to bed.'

Macbeth, Banquo and the Witches

(from William Shakespeare's 'Macbeth', Act I, Scene iii) 1793–1794

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825)

Around the same time in Britain, Swiss-born painter Henry Fuseli was painting similar subjects, including fairies and witches, but his inspiration was slightly different. Like many artists of this period, Fuseli drew inspiration from stories and mythology. There was also a fashion for painting scenes from Shakespeare, and witches appear in many of Shakespeare's works.

Though the narrative around witchcraft shifts across the centuries in Europe, one thing that remained consistent was its connection to women. The subject was leveraged as a way of commenting on women's beauty, sexuality and morality. In John William Waterhouse's painting titled The Magic Circle, we see a witch standing next to a smoking cauldron. Unlike the previous examples, she's fully clothed, youthful and relatively good-looking. She holds a wand in her hand as she draws a protective circle around herself. Inside the circle are beautiful flowers, and outside are frogs and ravens – both of which are associated with witchcraft. These ideas evolve into sexist perceptions of women as beings of loose morals that entrap men.

'By the time we get to Symbolist movement, which starts in the mid-nineteenth century and goes onto the beginning of the twentieth century, there is a nasty and sexual notion of women as the carriers and infectors of venereal disease, of women as hysterics, of women as hypocrites, or women as manipulative liars,' says Deanna. 'So many contemporary artists – particularly women artists – have found these attitudes distasteful. Artists are ... responding in a way to 'witch' being taken over as 'bitch'.'

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes