Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together popular culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

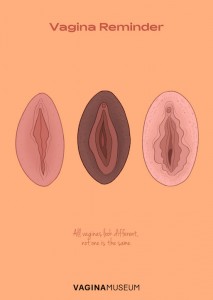

There are many ways to approach the topic of eroticism in art, especially if you factor in how different cultures engage with sexuality and the body. Museums around the world are filled with images of nude figures, and if you look at the Wellcome Collection on Art UK, as one example, you can see a number of images relating to sex, but erotic art is about more than just sex.

'The definition of eroticism means pertaining to the passion of love or concerned with treating love. It can also be extended to concerning or depicting the arousal of love', says Alyce Mahon, Reader in Modern and Contemporary Art History at the University of Cambridge, Curator of the recent Dorothea Tanning exhibition at the Reina Sofia Museum and Tate Modern, and author of Eroticism and Art. 'That's where perhaps it starts getting into more slippery zones because it engages with sexual love or giving sexual pleasure.'

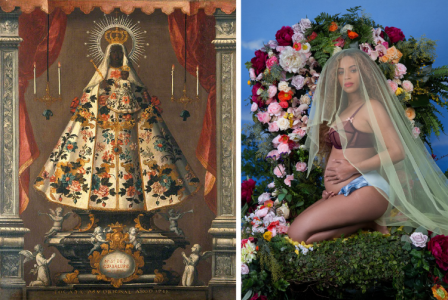

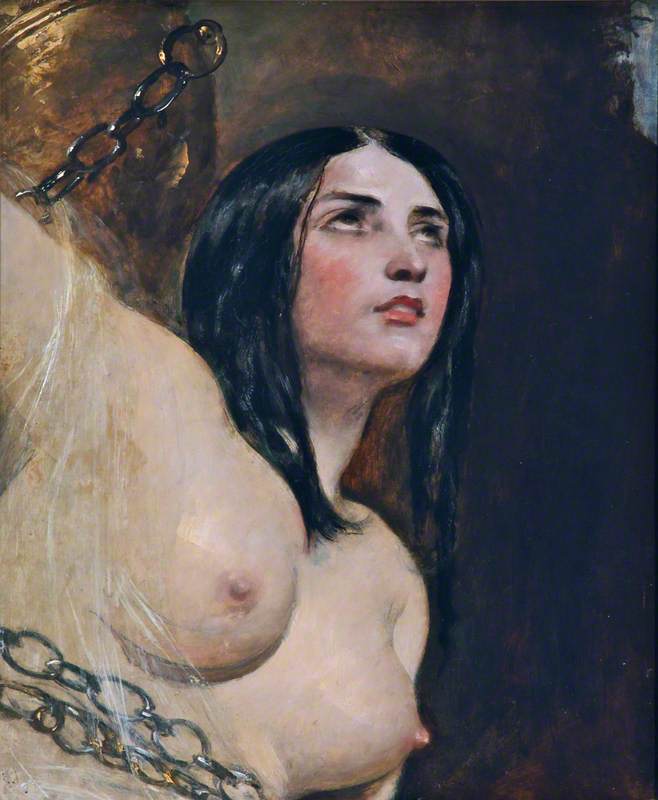

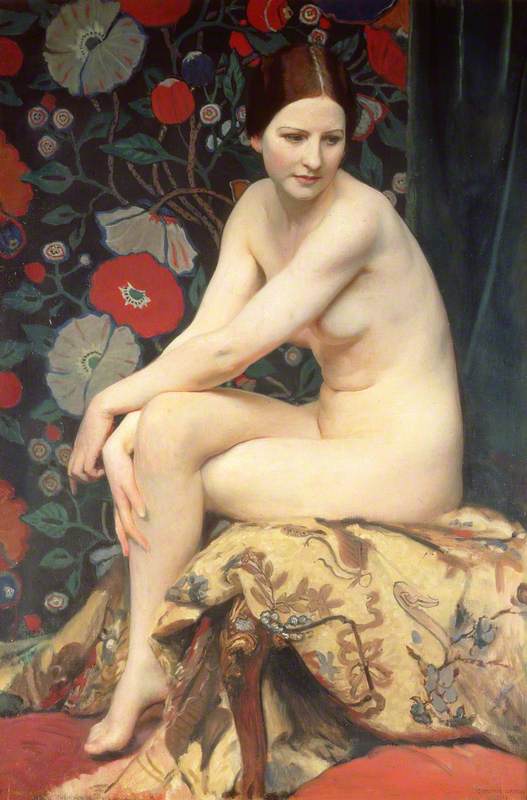

In our episode on hair in art, we discussed how even something as subtle as a woman wearing her hair down could have erotic connotations. What we may deem as erotic art has historically served a variety of purposes and is therefore reflected in different ways. Our personal viewpoints can also play a role in how we interpret works. For example, so much of western art depicts images of the nude body – does that mean those works are erotic? Alyce says no – nudity isn't a prerequisite for erotic imagery and it can be reflected in subtle ways that distinguish between love and lust.

In a discussion of sexual, erotic or nude imagery, there's scope for confusion about when an image crosses over from being erotic to pornographic. This comes down, in part, to intention. 'The erotic has ambitions beyond literally desire [and] sexuality. The erotic tends to be something that deals with morality, that deals with psychology, that deals with what's allowed,' says Alyce. 'The pornographic body would be there as a sexual aid – as something that has only got the desire to arouse sexual pleasure.'

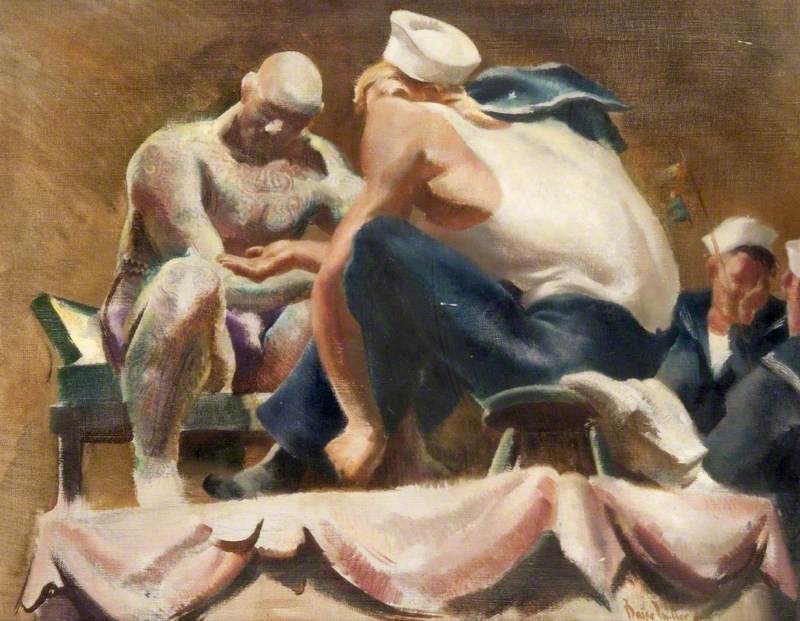

It's clear that erotic art is about more than sexuality and is even about more than what's overtly apparent. The twentieth century offers several examples of the relationship between social movements, historical events and artists' depictions of eroticism. Some artists were inspired by their experiences in the First and Second World Wars and what Alyce refers to as the 'mechanisation' of the body for war purposes. Later, women artists engaged with eroticism as a way of expressing what it meant to be part of a generation of 'new women'.

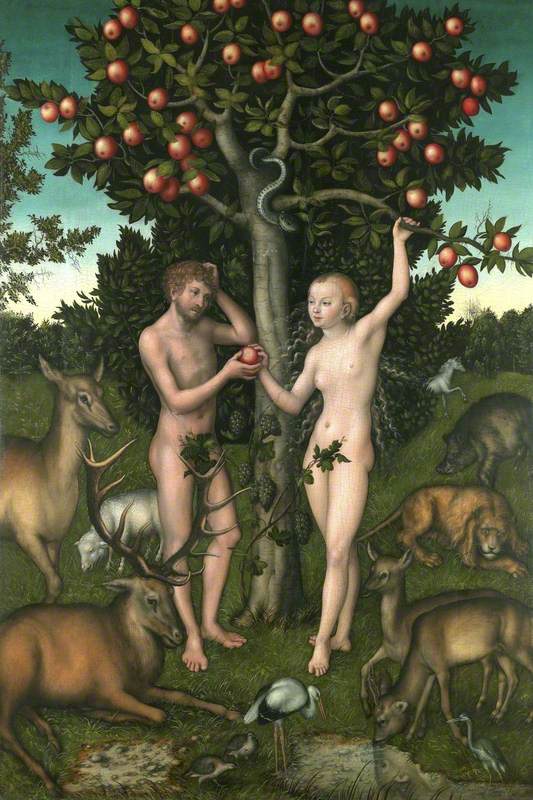

Throughout western art history, erotic subjects and imagery were often used as educational tools, encouraging high moral standards and cautioning the public not to overindulge in temptations of the flesh.

'The idea might have been that you would give a painting of a Venus and cupid to remind people watching it the importance of not having unbridled passion or unbridled lust, and the need to actually think about the mind and morality. And to think about virtue, rather than just vice', says Alyce.

One can apply this moralistic interpretation to John William Waterhouse's painting Hylas and the Nymphs, which shows Hylas from the Greek story of Jason and the Argonauts surrounded by seven nude water nymphs. In the painting, his preoccupation with their beauty has put him at risk of falling into the water and drowning. It's a direct connection between sexuality and potential peril.

In a painting from William Hogarth's A Rake's Progress series titled The Rake at the Rose Tavern, Hogarth depicts an orgy scene in a well-known London brothel. People are drunkenly strewn about the room and the women are covered with sores caused by syphilis. It's one of eight paintings that functioned as a cautionary tale warning against overindulging in vices, from gambling to sex.

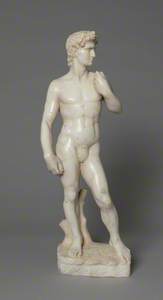

This idea of morality in connection with sexuality pervades the history of art and it is because of this that there came to be a distinction between art and pornography. In the nineteenth century, in particular, people sought to pin down clear denotations of 'eroticism' and 'pornography' to clarify what types of imagery and materials were socially acceptable. These kinds of discussions invariably lead to censorship, and the practice of censoring erotic works extends back centuries, changing with the tastes and fashions of the period. Censorship was even sometimes carried out posthumously, as was the case with some of the works of Michelangelo.

'There was a law issued at the time of Michelangelo's death in 1564 saying that the genitals in his artworks – even if they're referencing biblical subject matter, mythological subject matter – needed to be covered,' says Alyce. 'His famous statue of David depicting the battle between David and Goliath was adorned with a chastity girdle of twenty-eight copper leaves after 1564 because just the representation of genitals was seen to be something that was too erotic.'

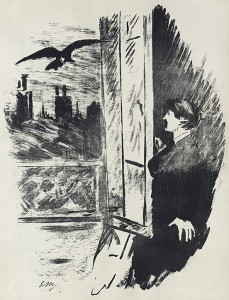

If erotic art isn't always explicitly sexual in appearance – with nudes and lusty gazes – you may be wondering how to recognise some of the more subtle erotic iconography. Images of Venus are easy to spot, with reclined female figures like those seen in the work of Titian and Manet. The inclusion of a dog may symbolise fidelity, while a cat can represent passion. Even something like a painting of a young woman, or girl, with a dead bird or dying flowers, can connote the loss of innocence.

Moving ahead to more recent art movements, the Surrealists were a group that believed strongly that eroticism played an essential role in art. The avant-garde movement began in early-1920s Paris and quickly spread across the world, lasting decades. They explored eroticism through engaging with imagery of the body, but also psychology.

Salvador Dalí made bold political statements through the eroticism in his work by exploring homoerotic desire at a time when the Nazis were gaining power and attacking homosexuality as 'degenerate'. 'The idea of him exploring same-sex desire wasn't just an exploration of his own self or an homage to what Surrealism was trying to do, but it was a very defiant political move,' says Alyce.

Dorothea Tanning takes yet another perspective in her Eine Kleine Nachtmusik by exploring the idea of burgeoning womanhood and being on the cusp of being a girl and becoming a woman, which includes sexual awakening amongst other bodily and psychological developments. It also taps into the psychology of dreams, which was a recurring theme in many Surrealist works.

I went into this episode expecting to discuss what turns out to be a surface-level interpretation of erotic art. It's a varied and nuanced genre that evolves with new mediums and changing societal norms.

'While we can't pin down eroticism every decade, it is the idea that it arouses something in us, we identify with it or we recognise it, at least, and there's an element of pleasure,' says Alyce. 'And that's something that we find at the heart of all art and why we still need it.'

Listen to the episode via the player or links at the top of this story to get even more interesting details and examples of erotic works. To learn more on this subject, you can pick up Alyce Mahon's books, Eroticism and Art (Oxford University Press, 2005 & 2007), Surrealism and the Politics of Eros: 1938–1968 (Thames & Hudson, 2005) and from 2020, the forthcoming The Marquis de Sade and the Avant-Garde (Princeton University Press).

The Dorothea Tanning exhibition at Tate Modern ends 9th June 2019.

Explore more

Lovesick blues: a short history of love and pain in art

Why are artists infatuated with red hair?

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes