Art Matters is the podcast that brings together pop culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

What is Black Girl Magic? Maybe you’ve heard the term or seen the hashtag in use. It’s a phrase first coined in 2013 on Twitter by

‘For

The great thing about conversations like this is that black art isn’t only for black audiences. We can all take something away from listening to each other.

The criticism of the phrase is important to note because some black women have highlighted that it could reinforce the stereotypes of the ‘strong black woman’ and its negative connotations, and could also have a dehumanising effect. This interpretation made me think of another term coined by director Spike Lee called the ‘Magical Negro’ – a character trope in which a black figure with some form of supernatural gift functions in a supporting role to aid a white protagonist. Examples of this have been pointed out across film and literature, including The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Shining, Ghost, The Green Mile and others. In the case of #blackgirlmagic, the phrase has been overwhelmingly lifted up as a way of celebrating black women and all of their achievements. It differs in spirit from the Magical Negro in that it’s an idea born of a black woman and used joyously by many black women and men.

In an era of the #metoo movement, feminism and women joining together to share our histories, I asked Bee to talk about why she feels it’s important to specifically champion black women’s voices.

‘My first encounters with feminism were very white,’ says Bee. ‘It was looking at the sort of issues white women were facing and not necessarily looking at the intersectionality of different forms of womanhood that exist. When you start to look at black women separately, you start to see similarities and differences in their experiences . . . If we want to uplift black women, we have to take this into account. We can’t just say sexism affects all women, but [ask] what happens when sexism and racism collide?’

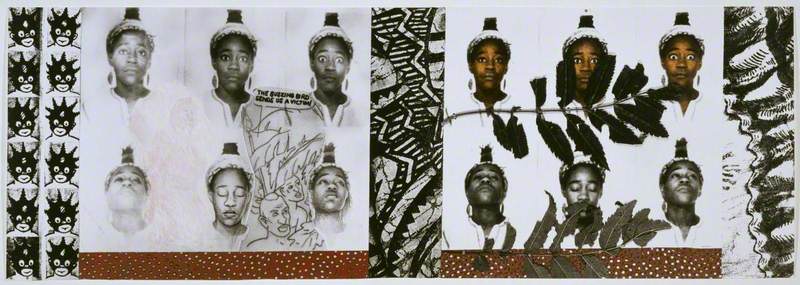

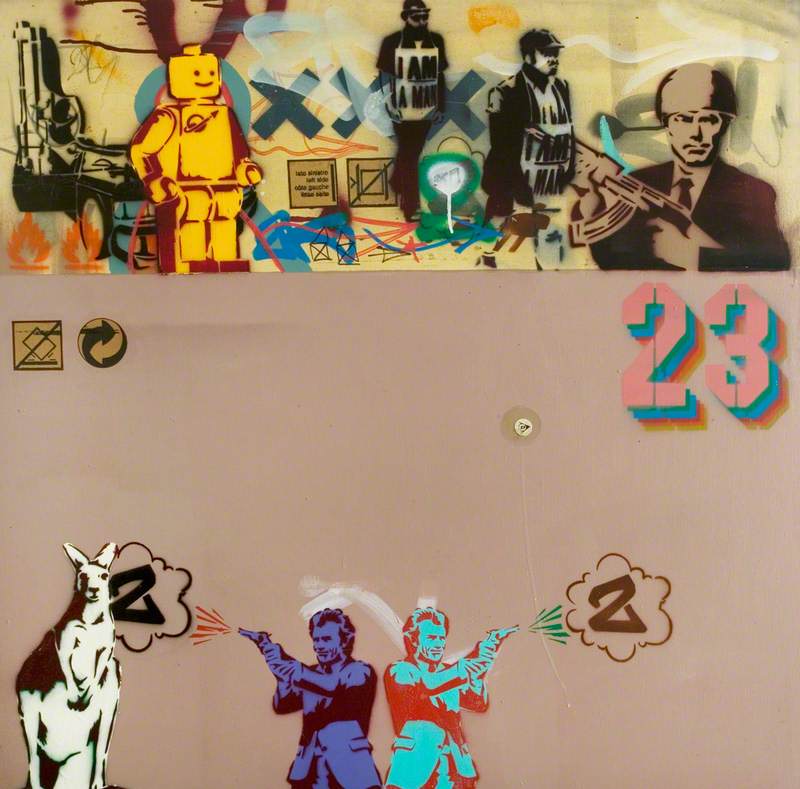

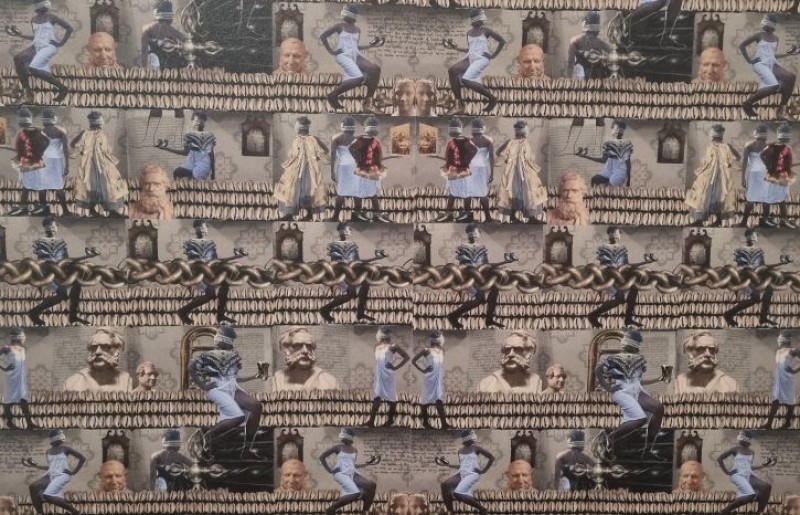

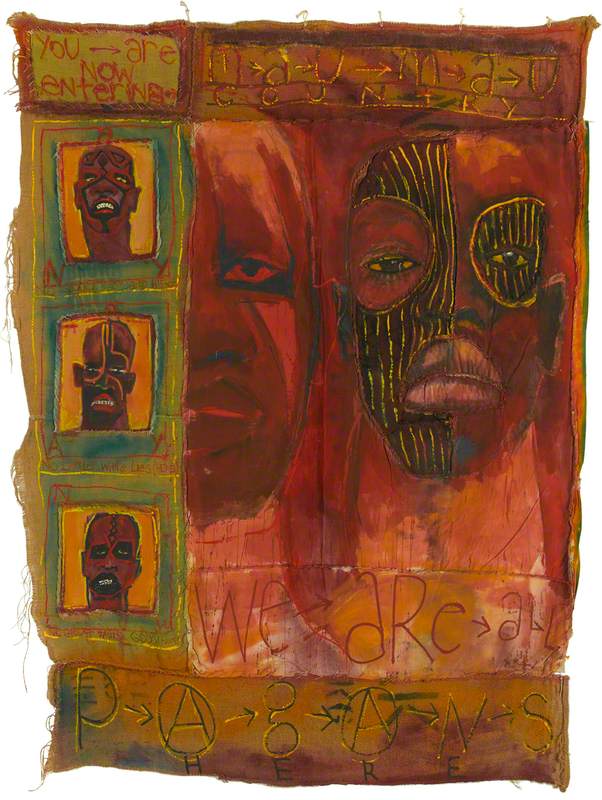

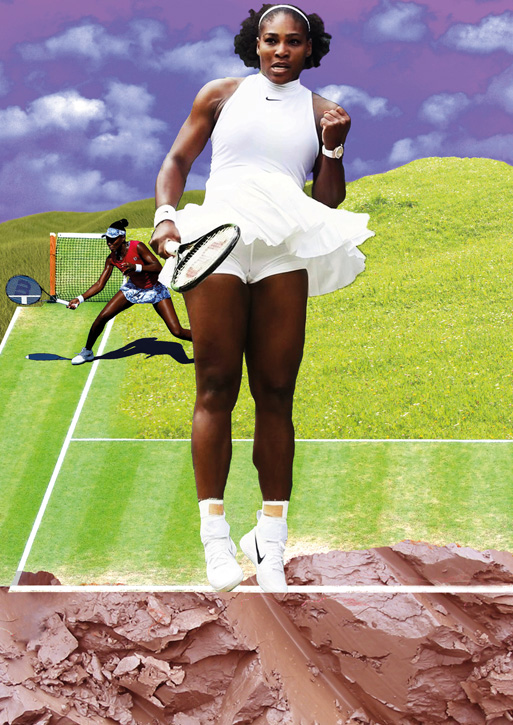

English Pastoral

2017, digital collage by Rosa Johan Uddoh (b.1993)

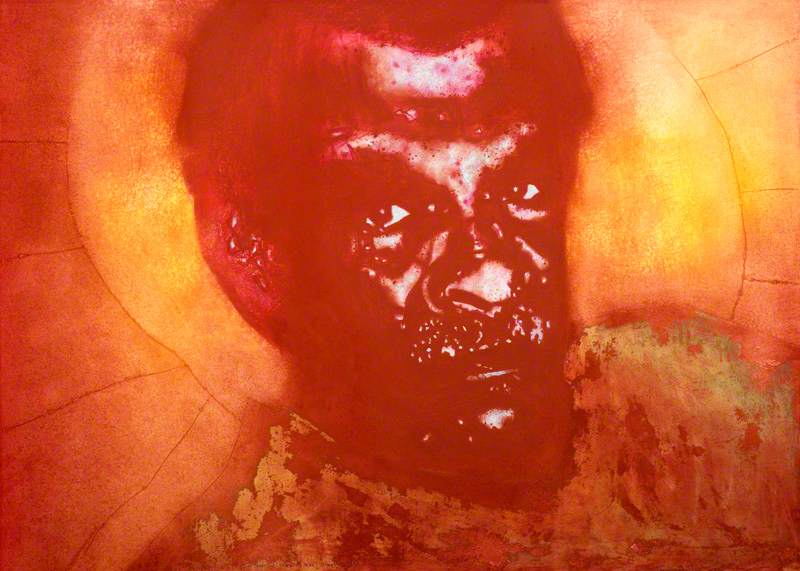

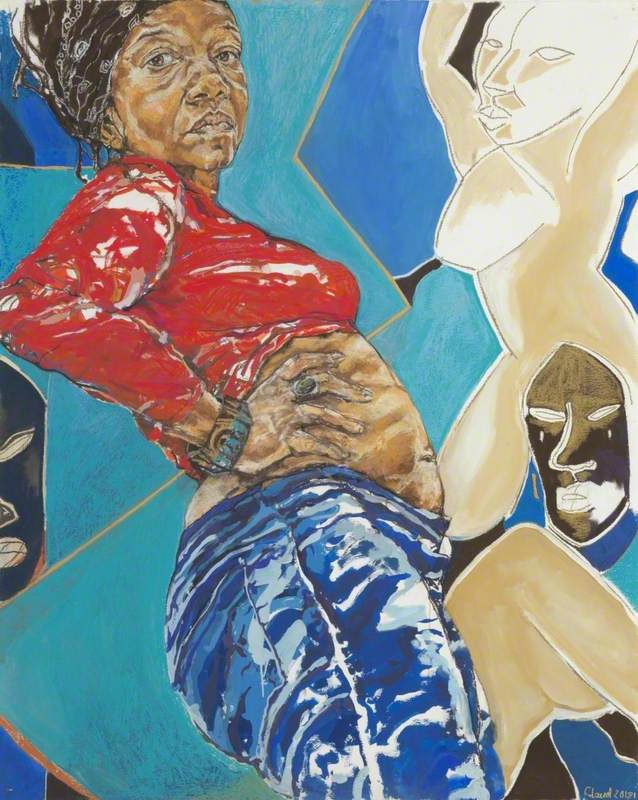

One of the ways Bee helps to amplify black women’s voices in art is through her Black Blossoms project, which holds exhibitions and events centring black women. It was born out of a desire to bring black women together in an environment where they felt invisible and has enabled artists to work together in a way that reduces some of the emotional labour that can come with addressing racial issues. One of the women Bee’s worked with through Black Blossoms is Rosa Johan Uddoh – an artist who uses representations of blackness in popular culture as a way of attaining higher self-esteem.

‘It’s a process of working through influences that have been in my life – particularly as a black woman. I do a lot of work looking back to childhood role models,’ Rosa tells me. ‘My process is one of engaging with the love and fandom that I have for these characters.’ Through these exercises, Rosa is able to see herself reflected in the people she’s admired throughout her life – people that mirror her own appearance and life – and boost her own self-esteem.

In the course of my conversation with Bee, we touched on black women and feminism in art, but she made a point to highlight some important nuances. ‘I’ve realised there is a need to separate that there are black women artists and there are black women artists working on black feminist art. I think it’s really important to separate the two,’ says Bee. ‘Black feminist art should be defined in its own category, and black women artists should also be a movement of its own, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that black women artists should bear the responsibility of making black feminist art.’

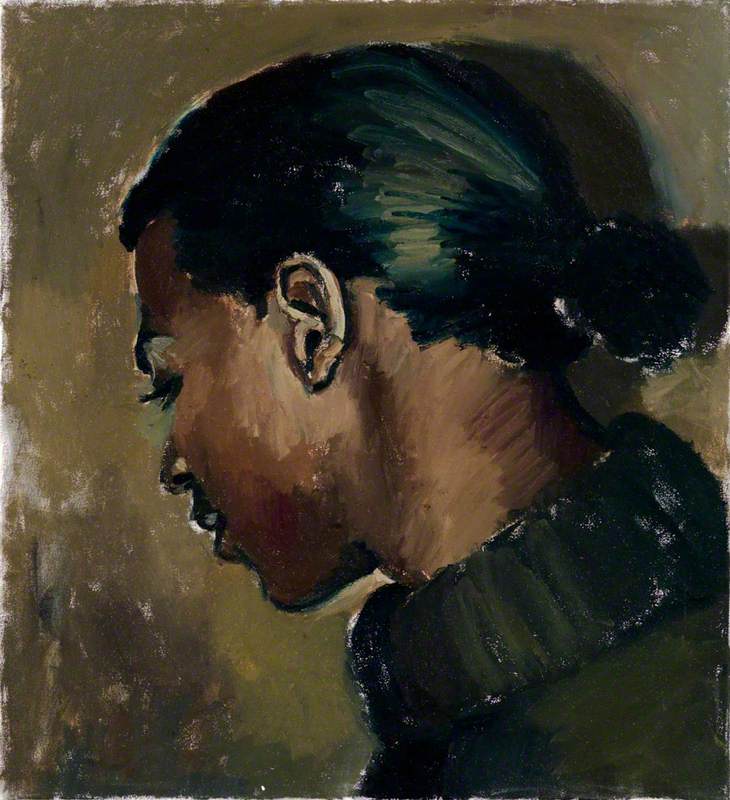

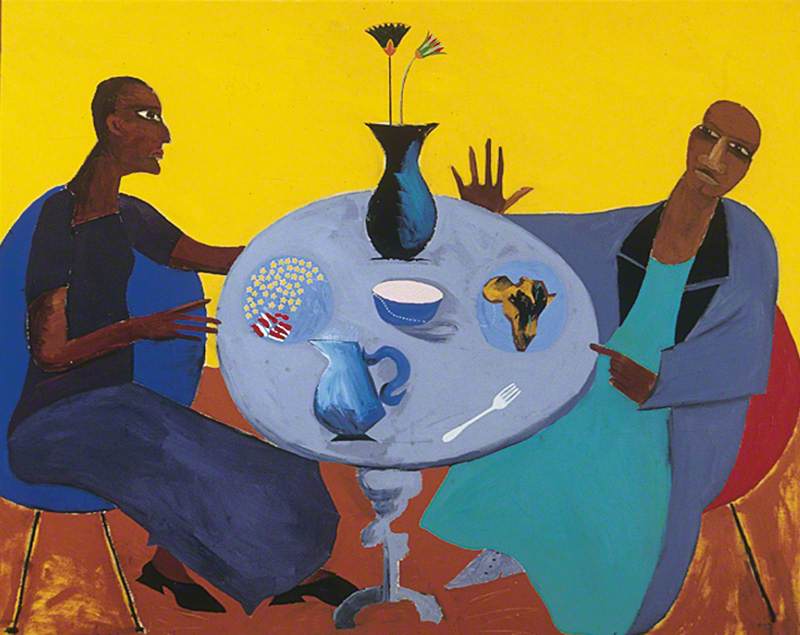

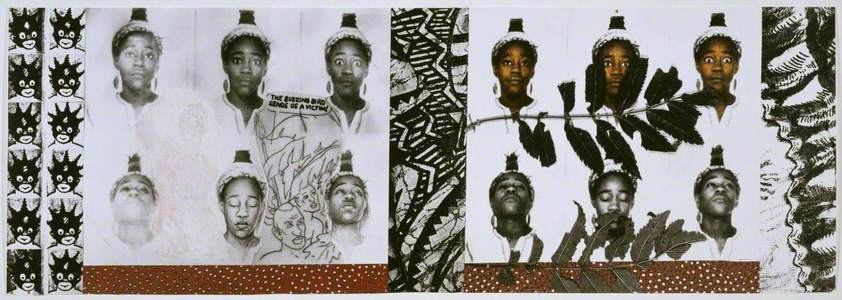

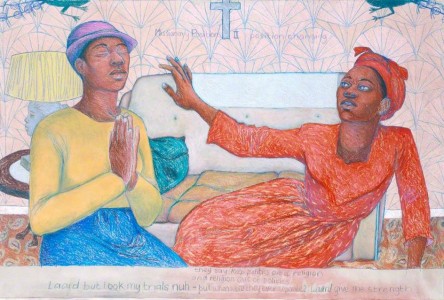

You may be familiar with Lubaina Himid, who won the prestigious Turner Prize in 2017. She was part of the UK’s Black Art Movement in the 1980s and was appointed an MBE for ‘services to black women’s art’ in 2010. You may also have heard about Anthea Hamilton’s recent installation at Tate Britain called The Squash – a fantastic performance piece examining the way we respond to imagery. Bee also spotlighted some other black women artists who can be found in the UK’s public collections, including Sonia Boyce, Barbara Walker, Claudette Johnson, and Zanele Muholi.

The great thing about conversations like this is that black art isn’t only for black audiences. We can all take something away from listening to each other. ‘If you’re viewing this sort of artwork it is only beneficial because it increases your knowledge of what other people go through. It gives you a wider worldview because it gives you a deeper understanding of all of the different sorts of identities that are present in the world.’

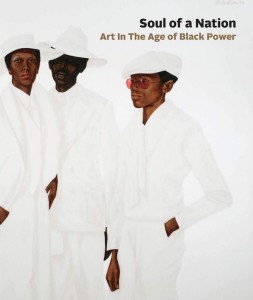

To hear my full conversation with Bee and Rosa, click the player above. Bee’s course on Art in the Age of Black Girl Magic at Tate Britain is sold out, but you can keep up with her work by following her on Twitter at Black Blossoms.

Explore more

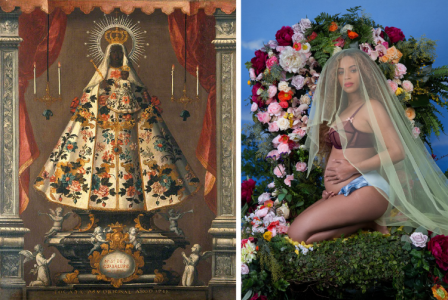

Art Matters podcast: when Beyoncé goes APES**T

The story of the Black Madonnas

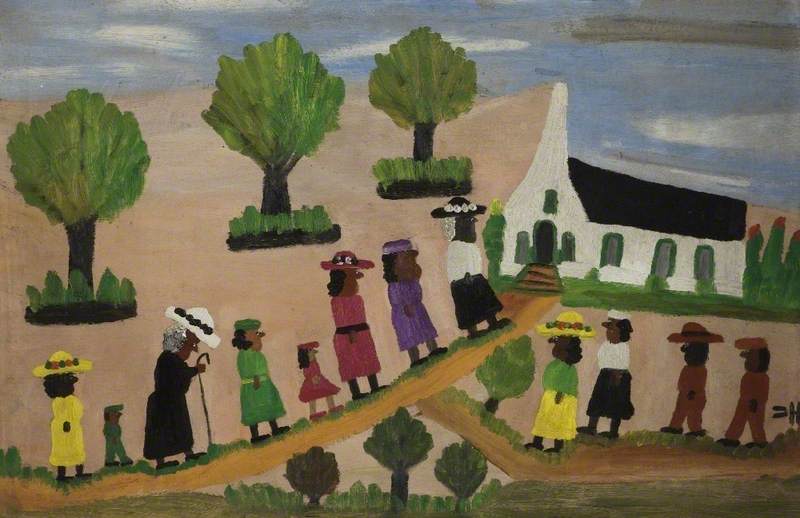

Celebrating the Windrush generation's impact on British art

Women painting women

Ten black British artists to celebrate

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes