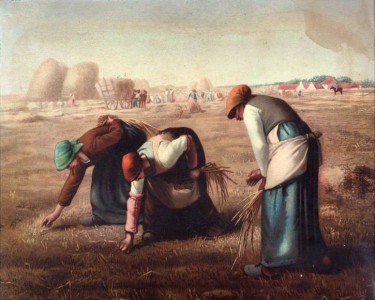

Can art change the future? In the nineteenth century, Victorian artists, viewers, and critics believed it could. As poverty, hunger, and disease all became increasingly urgent issues in industrial Britain, many artists began to consider how their work could benefit society.

Believing that art could change minds and spur action, they produced paintings, prints, and decorative objects that were designed to not merely comment on social problems, but actively participate in solving them.

'Art and Action: Making Change in Victorian Britain', coming soon to Watts Gallery (temporarily closed due to the latest COVID-19 measures), explores how art was used as a vehicle for social change between the 1840s and the end of the nineteenth century.

The exhibition explains how the Victorians turned to art to promote social causes and showcases the different artistic strategies they used to do so.

The middle of the nineteenth century was a period of extreme political unrest and deprivation. The Industrial Revolution had led to great wealth for some, but great suffering for many others.

Famine, financial depression, pollution, and stark social inequality characterised the period, and many people began to wonder how a prosperous nation could have allowed life to become so grim for so many of its citizens.

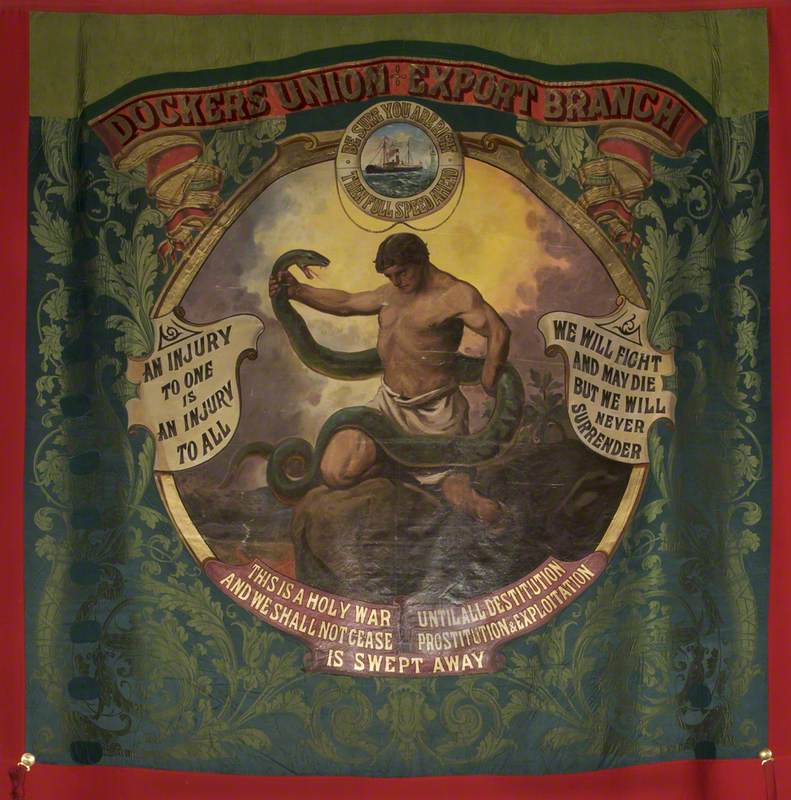

In response to these desperate circumstances, social movements formed to call for change. At the same time, public inquiries and news reports began to investigate social issues like dangerous factory conditions, abuse in the workhouses, and inadequate urban sanitation. For the first time, Britain's social problems began to be systematically documented and were being made increasingly visible to the broader public.

Victorian artists played an important role in this process. Many artists believed that art's purpose was to contribute to the general good and to improve life. They responded to the social concerns of their day by using their positions as public figures to write articles in political journals, donate their artworks to charity auctions, design banners or posters for social movements, or paint scenes that addressed the country's most pressing problems.

G. F. Watts' Song of the Shirt from 1847 represented the terrible circumstances in which seamstresses lived and worked, a topic that had recently come to public attention through a well-known report on labour conditions in the needle trades. The report revealed that seamstresses often worked for up to three days straight without rest and received hardly enough pay to allow them to survive.

Watts' painting makes the report's conclusions vivid and human, capturing the exhaustion and despair of a seamstress working into the early hours. For the young Watts, painting was a charitable endeavour. As he wrote to a friend that year, he hoped to sell enough paintings so that he always had money to give to those living in poverty.

Victorian artists were at the frontline of reform efforts, using their art to develop strategies to confront the most urgent social problems of their day.

Many artists also hoped that their paintings would bring social issues into the view of audiences with the influence and financial means to take action. By exhibiting their work at fashionable exhibition venues, artists were guaranteed a large and influential audience. Paintings about contemporary social problems became increasingly popular, taking the place of the historical paintings, landscapes, and portraits that had previously dominated exhibitions.

By 1875, the critic John Ruskin wrote that so many social scenes were displayed at that year's Royal Academy exhibition that the walls looked as though they were papered with issues of an illustrated newspaper.

Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward

1874

Luke Fildes (1843–1927)

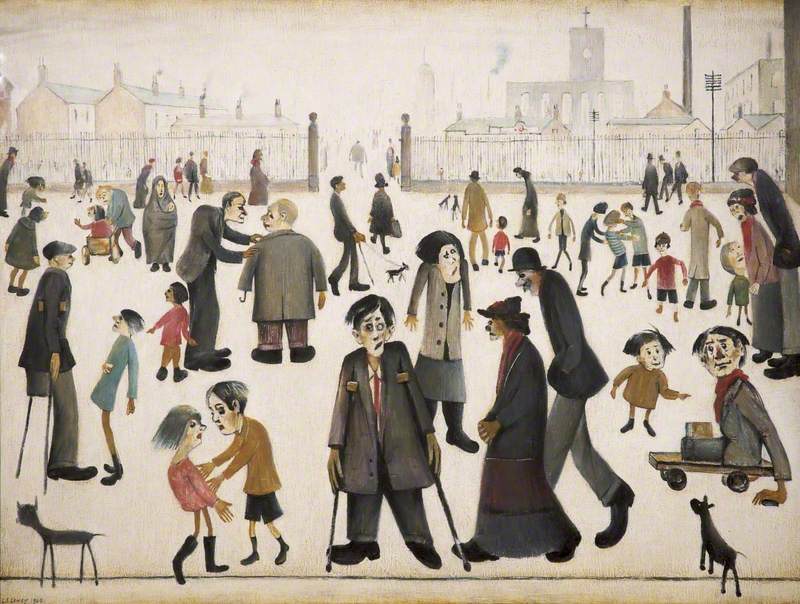

Luke Fildes was one of the artists whose work most reminded viewers of newspaper illustrations, and for good reason. Fildes began his career as a graphic artist, designing news illustrations of London street life. One of his best-known newspaper illustrations was the inspiration for his 1874 painting Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward, which shows people queuing for tickets to a London night shelter, known as a casual ward.

When the painting was exhibited, it shocked audiences by depicting poverty more realistically than many had seen before. While some critics found the painting emotionally painful and visually ugly, others saw its frankness about poverty as a call to arms that compelled its viewers to take action.

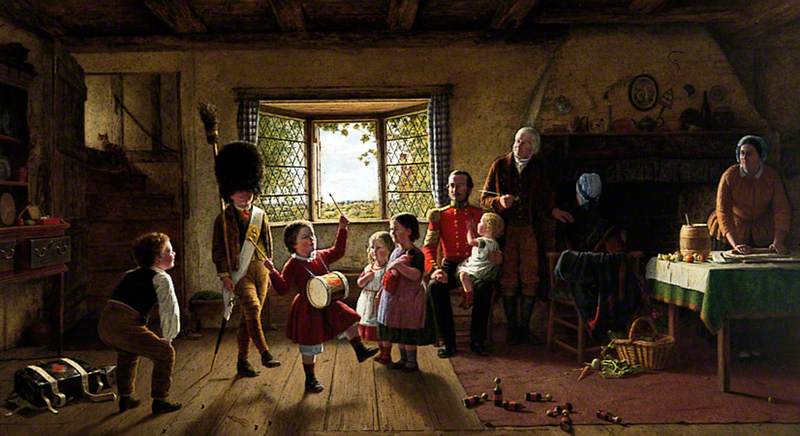

If Fildes stoked his audience's sympathy through realism, Thomas Kennington did it through idealisation. In his 1891 painting The Pinch of Poverty, a pretty little flower seller supports her mother and siblings by selling daffodils. Although the family is dressed in tattered clothes, showing that they have fallen on hard times, they are portrayed as attractively and sympathetically as possible to gain the viewer's compassion.

In the scene, the flower seller appears to approach us, the painting's viewers, to offer her wares, giving us the chance to buy a flower and relieve some of the family's suffering. By appealing directly to its viewers, the work suggests that every one of us is responsible for coming to the aid of those who are less fortunate.

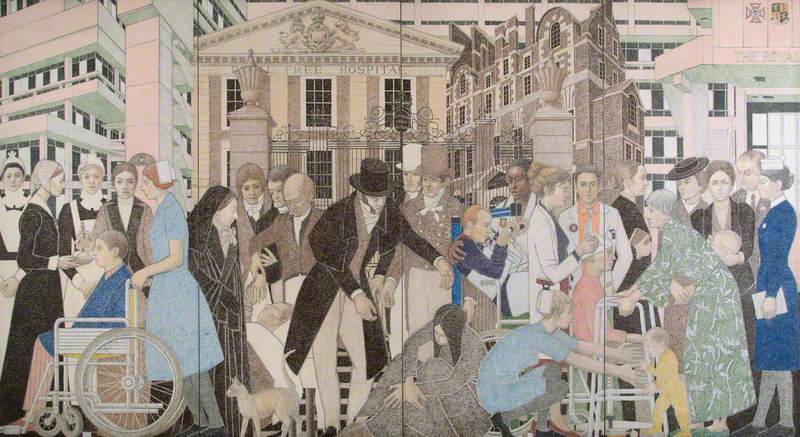

In their effort to address a wide range of social issues, Victorian artists were just as concerned with pandemics and public health as we are today. By painting The First Public Drinking Fountain (1859), W. A. Atkinson issued a public service announcement to help quell London's cholera epidemic. Cholera, which spread through diseased water, had caused millions of deaths in a series of pandemics during the nineteenth century.

This painting commemorated the opening of London's first drinking fountain, which brought clean water to the residents of Holborn. By depicting members of all classes amicably using the fountain together, Atkinson's painting reminded viewers that the epidemic would only end if all Holborn's residents shared the same clean water, and put hygiene and health above class differences.

Victorian artists were at the frontline of reform efforts, using their art to develop strategies to confront the most urgent social problems of their day. They hoped that their artworks would change minds, inspire discussion and debate, and shape public discourse in ways that could lead to broader social change.

'Art and Action: Making Change in Victorian Britain' reveals how art came to be recognised as an important political tool that the Victorians believed had the power to shape the future.

Although the exhibition is closed temporarily, the curator-led video tour is available at the Watts Gallery website, which allows audiences to experience the exhibition from home.

Chloe Ward, Curator of 'Art and Action: Making Change in Victorian Britain'