Artists have long been attracted to north-west Wales, ever since the pioneering Welsh landscape artist Richard Wilson captured the grandeur of the region in the mid-eighteenth century. Thereafter, countless others followed, drawn by the drama and atmosphere of the natural landscape – the lofty mountains, rugged terrain and expansive views.

But how many artists turned their attention to the distinctive man-made landscape of north-west Wales: the jagged grey mountainsides hewn and shaped by intensive slate quarrying? And what place does slate – and the landscape associated with it – have in the visual arts?

UNESCO recently designated the slate landscape of north-west Wales a World Heritage Site. The designation highlights the historical and cultural importance of six slate quarrying areas and the communities that formed around them.

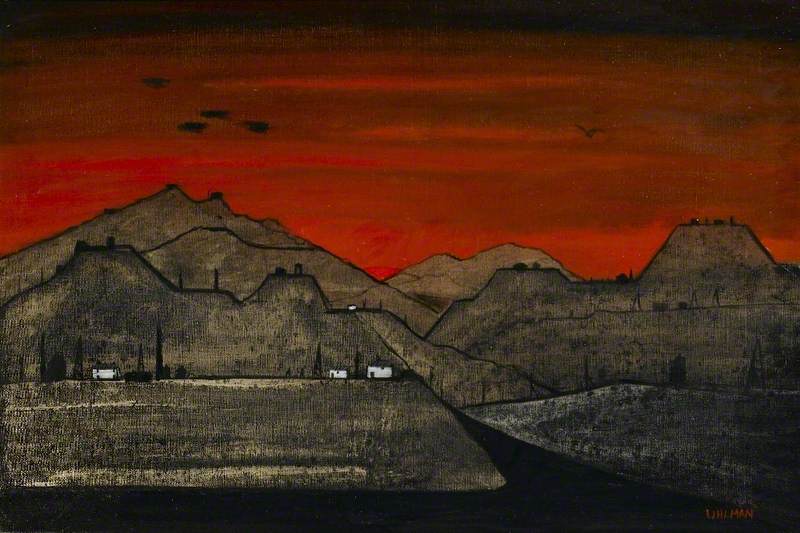

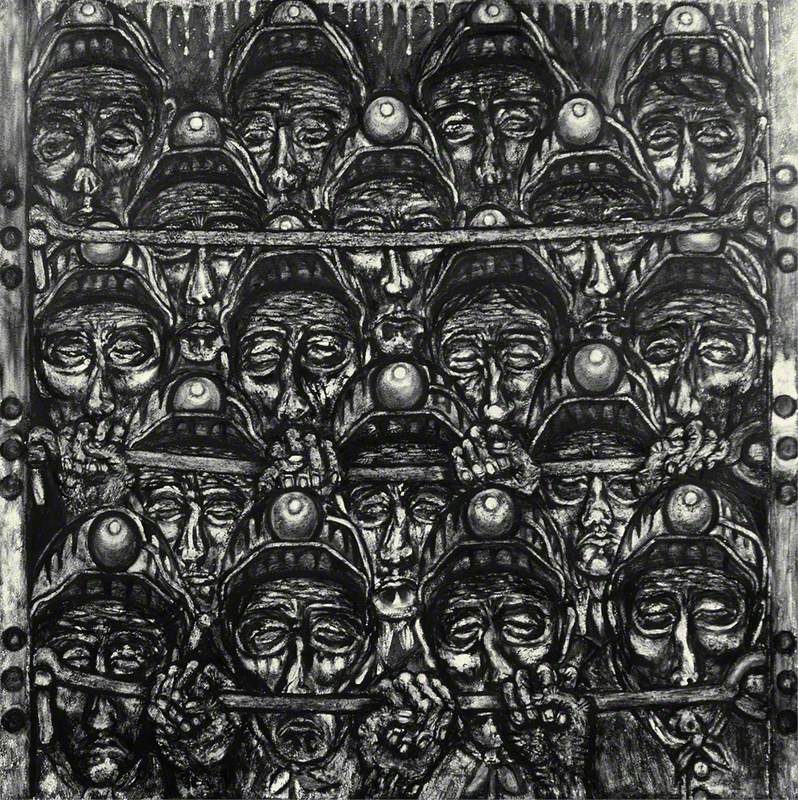

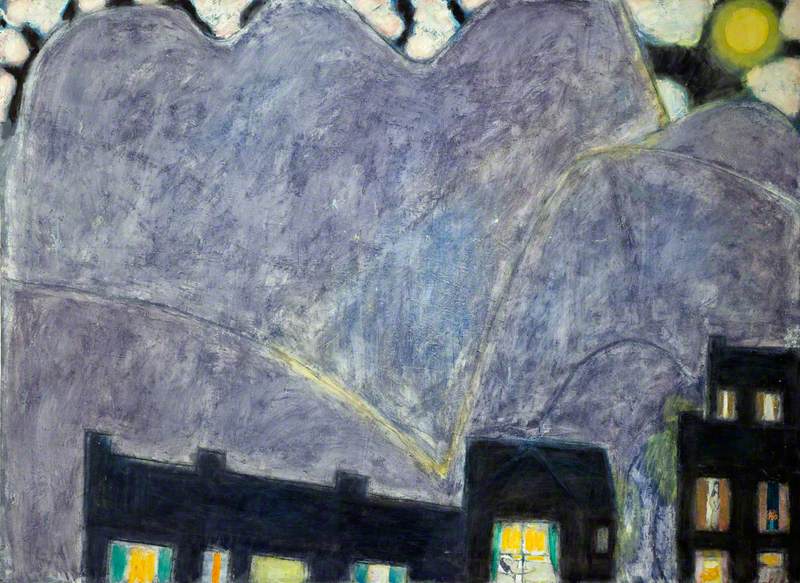

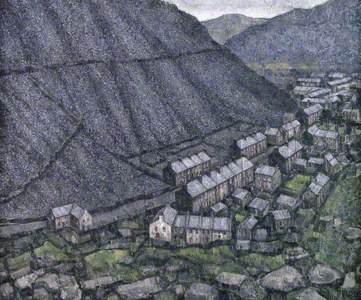

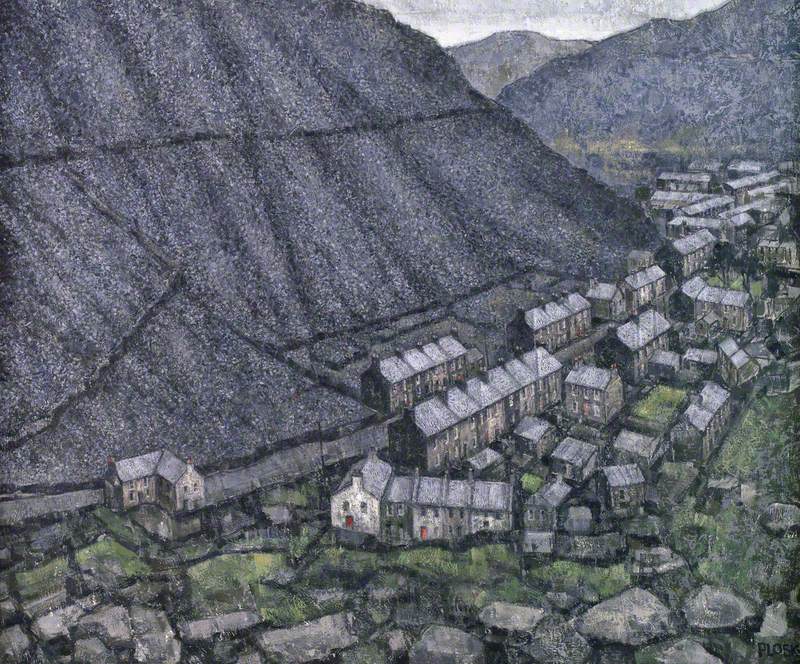

Grey Shades, Blaenau Ffestiniog

1970s

Jonas Plosky (1940–2011)

A few decades after Wilson painted his views of Snowdonia, this mountainous region was transformed by the rapid growth of the slate industry. While small quarries had long existed in the area, they experienced a boom with the Industrial Revolution as the growth of large cities fuelled the demand for roofing slate.

By the late nineteenth century, this small corner of Wales had become one of the world's leading providers: Welsh slate represented about a third of global production. Shipped around the world, it was used for roofing, architectural purposes, school blackboards and writing slates.

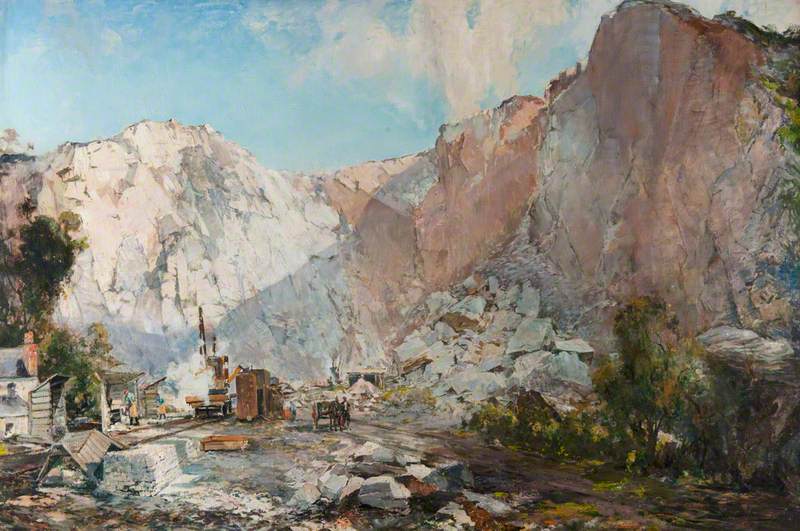

The intensity of quarrying activity is captured in a painting of Penrhyn Quarry near Bethesda in the Ogwen Valley, painted in 1832. The artist, Henry Hawkins, presents an awe-inspiring scene, showing the quarry as a marvel of the industrial world. Developed in the 1770s, it was one of the largest mines in the world by the end of the nineteenth century.

Hawkins includes himself at the bottom right, painting the hundreds of quarrymen scaling the sheer rockfaces with pickaxes. Their minuscule figures are dwarfed by the monumental walls and seemingly endless pit: they appear as tiny cogs in a sleek, well-oiled machinery – a perspective that no doubt pleased the painting's first owner, who also owned the quarry.

At the time this picture was painted, the quarry was owned by George Hay Dawkins-Pennant, who had inherited it from his father's cousin, Richard Pennant, 1st Baron Penrhyn.

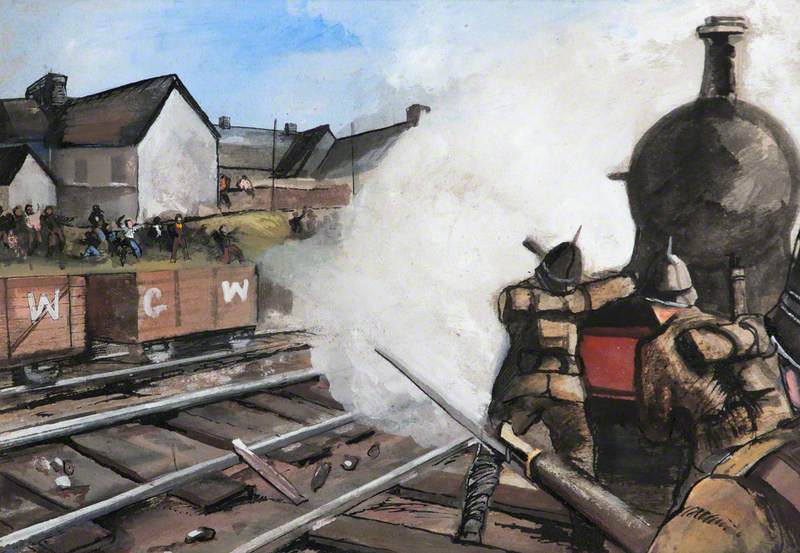

The vast Penrhyn fortune was accumulated through sugar and slate, which profited from the enforced labour of enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean and the exploitation of local workers in Wales. The salaries earned by quarrymen were low and their working conditions dangerous, which prompted two strikes: one in 1896 and then The Great Strike, which began in 1900 and lasted three long years. Six months into the dispute, some men returned to work, leading to bitter rifts in the community that persisted for generations.

As well as being workplaces, the largest quarries also became tourist attractions. As early as the beginning of the nineteenth century, Penrhyn quarry was already attracting visitors eager to witness its extraordinary man-made landscape for themselves. In 1832, the year Hawkins painted his picture, a teenage Princess (later Queen) Victoria visited the quarry. A group of well-dressed visitors can be seen gathered at the edge of the pit in another nineteenth-century depiction of Penrhyn quarry.

Penrhyn Slate Quarry, Property of Lord Penrhyn

19th C

unknown artist

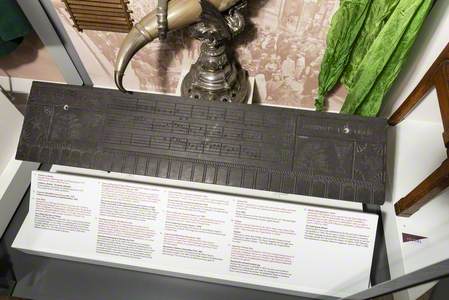

This painting is on slate, reminding us that the quarries were the source of an artistic material – slate, which was often carved and sculpted by local quarrymen.

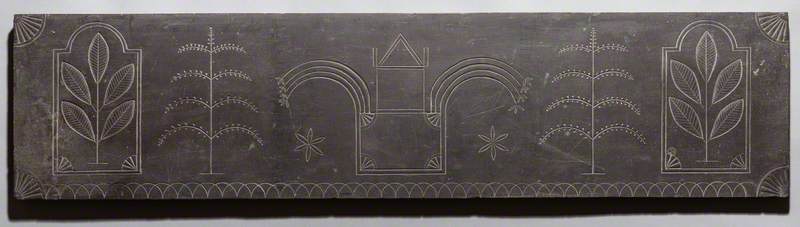

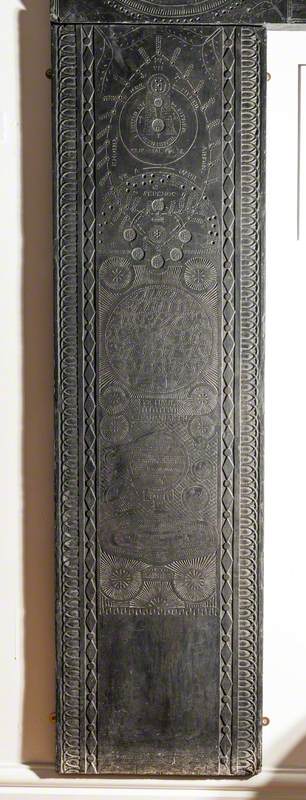

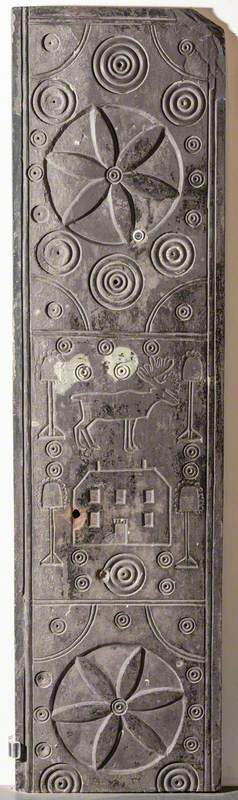

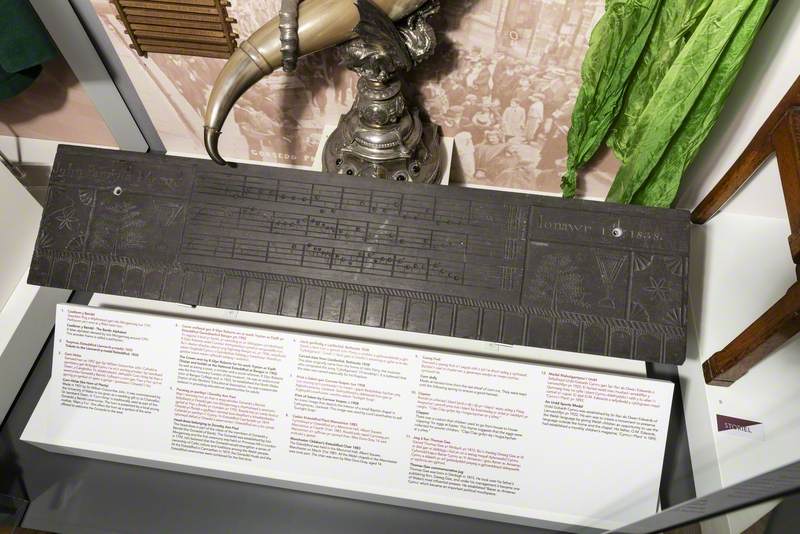

This was a popular art form – a type of folk art – enabling workers to put their fine cutting skills to creative purposes. They carved intricate motifs, from decorative flowers and foliage, to astronomical elements such as circles and stars, and figurative motifs such as houses or animals, and sometimes even musical scores.

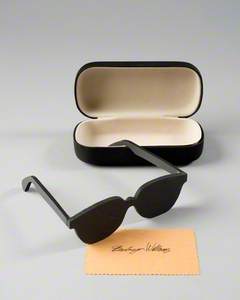

Like samplers, these carvings were highly personal, reflecting the interests of each individual maker. The slates vary in size and shape: from long rectangular panels intended as fire surrounds to three-dimensional objects such as fans or small-scale furniture. Most known examples were made for domestic purposes and derived from the Ogwen Valley from the 1820s to 1840s. This tradition was revived by contemporary Welsh artist Bedwyr Williams, who in 2008 fashioned a modern consumer fashion item – a pair of sunglasses – from slate.

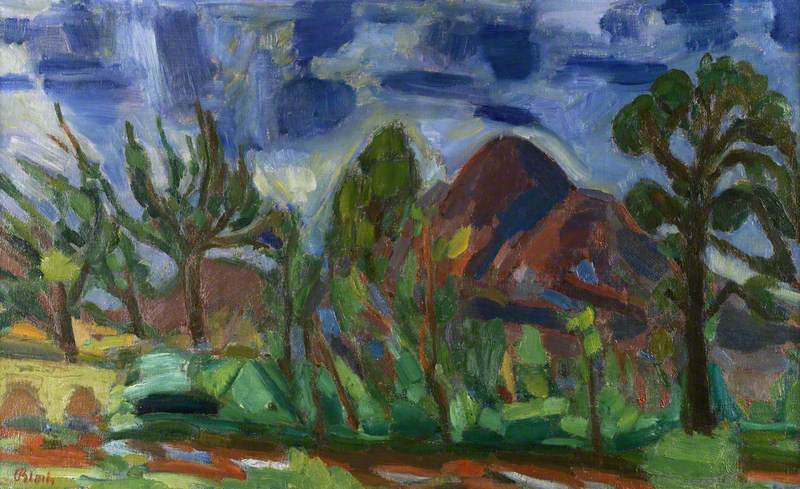

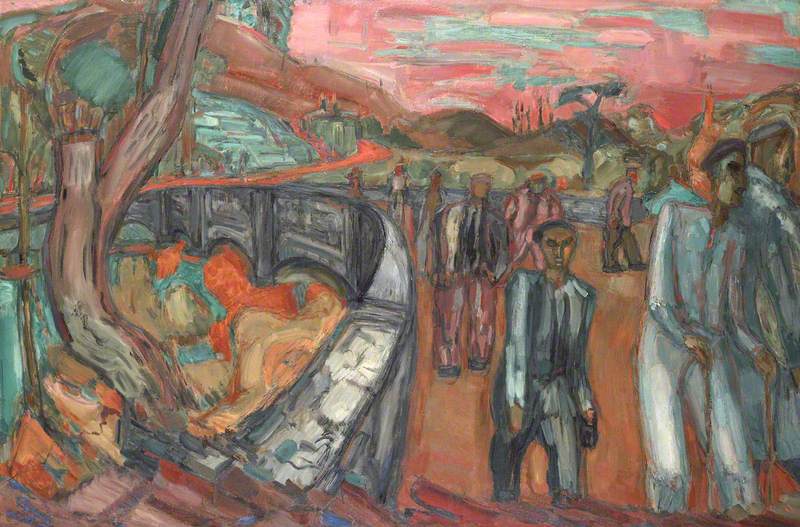

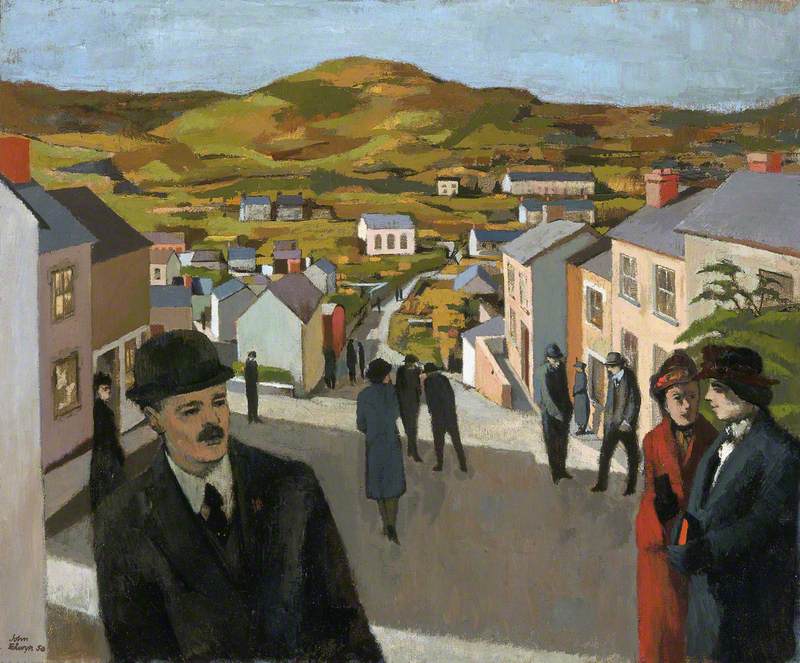

Over the course of the twentieth century, the slate landscape and communities of north-west Wales continued to inspire artists. German-Jewish artist Martin Bloch depicted workers returning from the quarry in a painting that was exhibited at the 1951 Festival of Britain. You might expect a slate landscape to be grey, but Bloch infuses the scene with vibrant colours, animating it with curving lines – revealing the influence of German Expressionism and Bloch's formative years in Berlin, Munich and Paris.

He fled to Britain from Nazi Europe in 1934 and though based in London, he often visited Wales during the post-war years. His friend and fellow emigré Josef Herman had settled in Ystradgynlais in south Wales, and while Herman was drawn to coal miners, it was north Wales's quarrymen that attracted Bloch.

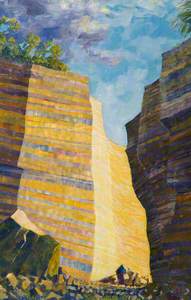

Another emigré artist from Nazi Europe who spent time in north-west Wales was Fred Uhlman. Originally from Germany, Uhlman was based in London but had a house in the Croesor Valley near Blaenau Ffestiniog, once known as the 'slate capital of the world'. During his summers there, he often painted the slate mines, focusing on their jagged silhouette – either painting the quarries' outlines in a bright, luminous tone, or setting their notched, uneven forms against a fiery sky.

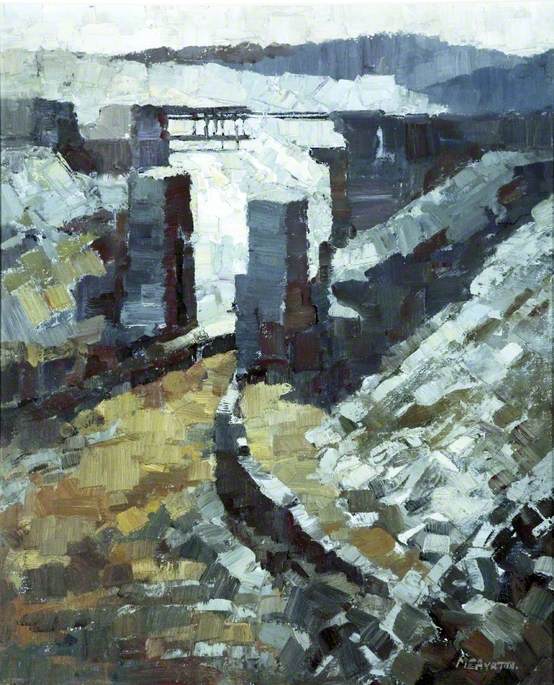

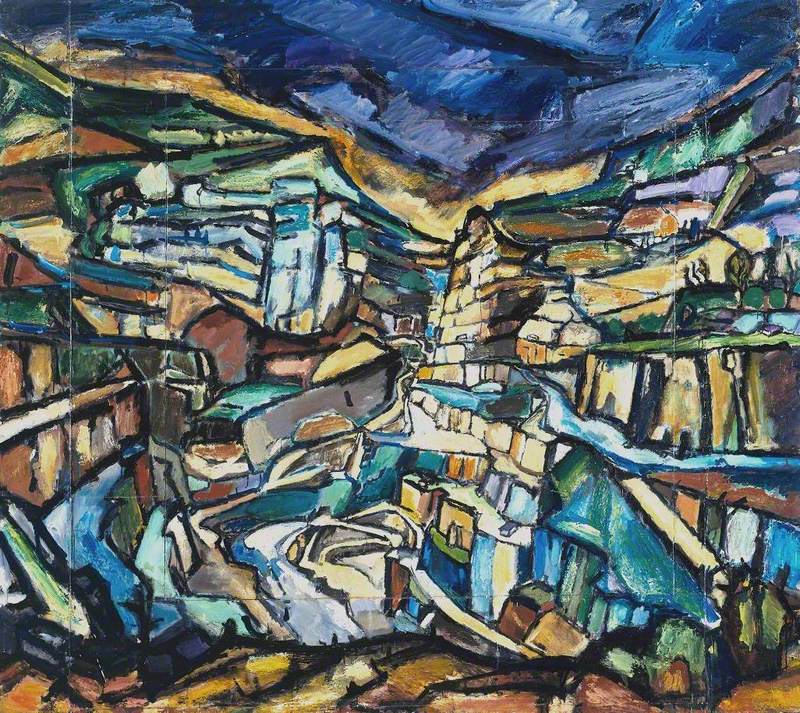

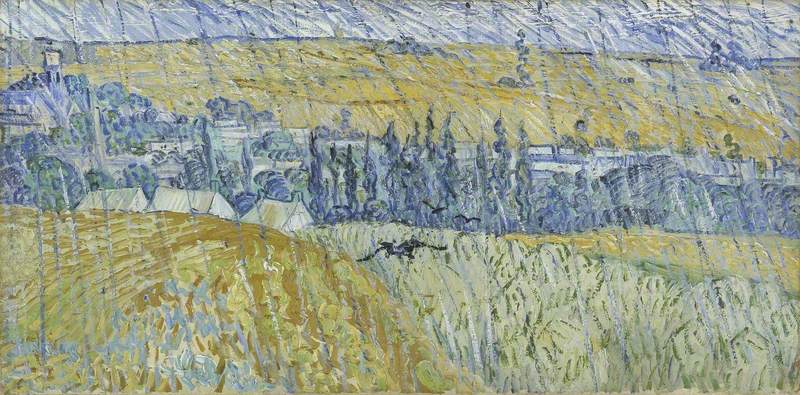

The slate landscapes around Blaenau Ffestiniog and Bethesda were also an enduring inspiration for Peter Prendergast. Originally from a coal mining area in south Wales, in 1970, Prendergast settled in Deiniolen, a village built for workers at Dinorwig Quarry. Whether painting the quarries themselves or the landscapes and towns surrounding them, Prendergast conveyed the robust, hardy character of the region with broad patches of strong colour applied with strong gestural brushstrokes, often outlined in black.

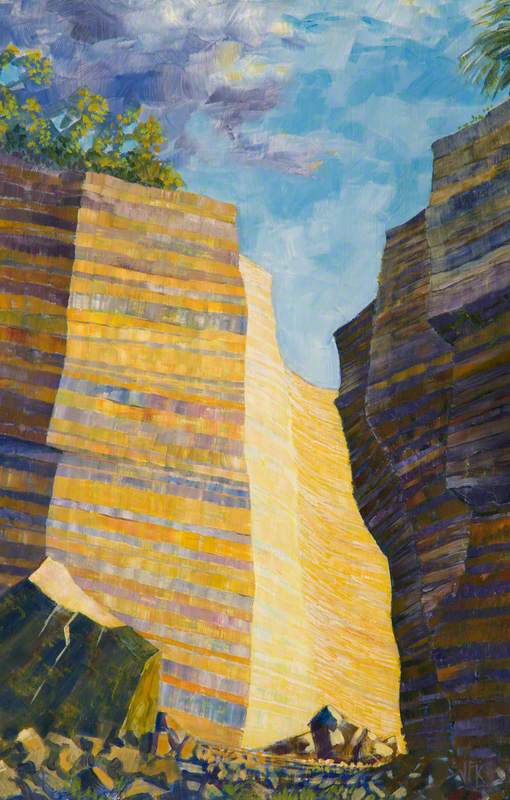

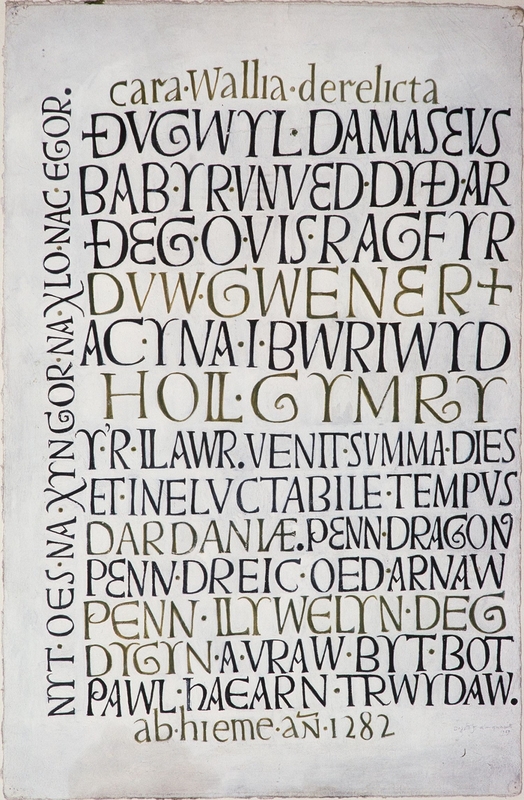

The scarring of the land through centuries of mining – be it lead in Ceredigion or slate in Snowdonia – is a central theme in Mary Lloyd Jones's work. She also explores the connection between landscape and cultural and linguistic identity. In Dyffryn Nantlle, Llais Nantlle she finds inspiration in the same valley once depicted so idyllically by Richard Wilson: Nantlle, where a series of small, deep, independent mines were developed from the early nineteenth century. Her title – the 'voice of Nantlle' – is given visual expression in the marks at the upper right, reminiscent of the early Ogham and Bardic alphabets. It is a reminder that the Welsh language was integral to the slate mining communities and the land on which they worked.

Dyffryn Nantlle Llais Nantlle

1996

Mary Lloyd Jones (b.1934)

Lastly, as well as being the subject of art, one of north-west Wales's slate quarries once became a repository for Britain's greatest artistic treasures. During the Second World War, the disused Manod quarry was chosen as a refuge for the nation's most precious paintings. In 1940, Winston Churchill stated: 'Hide them in caves and cellars, but not one picture shall leave this island.' And so it was that between 1941 and 1945, the National Gallery's collection was housed in this remote subterranean location in the hills above Ffestiniog – a secret National Gallery in the slate caves of north Wales!

From depictions of slate quarries to works of art inspired by them, and from slate as an artistic material to the hidden galleries within a quarry, the connections between art and slate in north-west Wales are as multi-layered and numerous as they are rich.

Mari Griffith, writer and art historian

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding