The concept of a rockstar dates only from 1960, yet the phenomenon is neither modern nor dependent on TV or the media. In fact, Angelica Kauffman was the equivalent of a rockstar in the eighteenth century. Her engraver coined the term 'Angelicamad' to capture the extreme adoration the public displayed toward her. People in the streets of London are said to have fought over ribbons from her hair. She was revered not only for her artistic accomplishments but for her rags-to-riches story. Seven decades after her death, a romance novel loosely based on her life, Miss Angel, became a bestseller.

But then she disappeared. Even among academic art circles, it was as if she'd never existed. As a ten-year-old in the 1950s, I audited art history courses at an American university. Angelica Kauffman? Never mentioned. When I took those courses again in college, it was the same.

Despite the notoriety she enjoyed during her lifetime, the male-dominated art world overlooked Angelica Kauffman for generations. The extent of this erasure was deeply intertwined with her gender. Her mentor and friend Sir Joshua Reynolds, for example, whose portrait she painted sitting pensively at his desk, didn't disappear from the public eye. But she did.

Plenty of male artists – think Bouguereau or Alma-Tadema – have fallen out of fashion over time, but their work remained within the broader narrative of art history, even if their style was no longer favoured. It is no coincidence that, while Angelica was one of two female founding members of the Royal Academy in 1768, it was not until 1922 that another woman was elected to the Academy.

Only after having taken a different career direction, did I run across Angelica by accident around 1990. The art world had finally begun to reverse its erasure. Diving into research mode, I read everything I could find – Francis Gerard's biography; Anne Thackeray's novel; Wendy Roworth's monograph, once it became available in the US; and all six mentions of Angelica on the web at that time. As I became acquainted with the facts of her life and work, a deeper question arose: How did this woman become a rockstar?

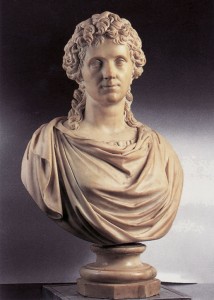

The Artist in the Character of Design Listening to the Inspiration of Poetry

1782

Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807)

She didn't do it by living according to conventional expectations. She did it by following her internal drive to create, regardless of the dictates of her time. One of those dictates was marriage, which made a woman the possession of her husband. Angelica, as I understand her, vowed not to be bound in that way.

Though history painting was off-limits to women, she refused to let that stop her. At age 23, she was already producing history paintings, such as Penelope at Her Loom, her faithful dog at her side, illustrating the myth of Odysseus. She continued to paint portraits throughout her life, but largely for the income.

Angelica also painted numerous self-portraits, which provide insight into her view of herself. We see her as an artist dressed in flowing Grecian robes – the attire of the Greek goddesses and heroines in her history paintings. It is as if she were willing the rockstar into being. By contrast, when Nathaniel Dance-Holland painted her portrait, though she held a paintbrush, she wore a modest dress with a high neckline and a heavy fur pelt.

The more I discovered about Angelica, the more I felt compelled to write a novel that could bridge the centuries and bring forth the woman behind the rockstar. I started my analysis at the end of her life, with the letters she wrote to Wolfgang von Goethe, and worked backwards. I let her speak to me, and I listened not just as a historian but as a psychologist, an artist and a woman.

In the process, I considered how she negotiated her personal relationships and how each helped or hindered her artistic success. Tracing the vows she made, I envisioned her marriage to the imposter who claimed to be a Swedish count; her intimacy with Joshua Reynolds; her sulky second husband, Antonio Zucchi; and her beloved Wolfgang Goethe. My version is fiction, but sometimes fiction holds a greater truth.

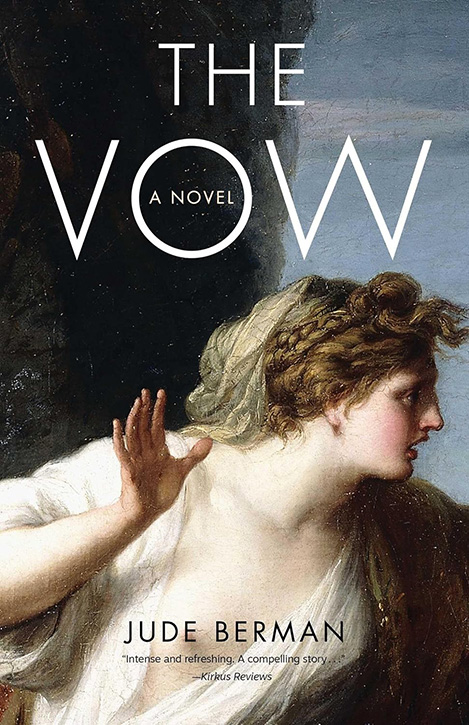

The Vow: A Novel

Jude Berman (2024)

The cover designer selected an image from one of Angelica's paintings of Ariadne, not knowing the goddess is discussed in the book. In fact, written from the first-person point of view, these words give us a window into Angelica's mind: '[Ariadne] does not crave what I crave. Nor would she ever make a vow that sacrificed her chances at love. Of course, to paint her, I must understand her', and 'her outstretched arm and radiant breast will highlight the courage with which she faces her own pain. All women, I believe, need such courage.'

Jude Berman, author and artist

The Vow: A Novel is published by She Writes Press