Maurice Wade is a rather mysterious figure. Little is known about the artist's biography, and still today, not a single photograph has been located. Yet despite his elusive presence in British art history, the sombre industrial landscapes of Wade continue to inspire and captivate. Precise, tranquil and muted, his large-scale paintings pay homage to the urban sites of northern England – in particular, North Staffordshire – without resorting to sentimentality or nostalgia. His works can currently be viewed at 'Maurice Wade, Silent Landscapes – The Andy McCluskey Collection' at Trent Art, Newcastle-under-Lyme.

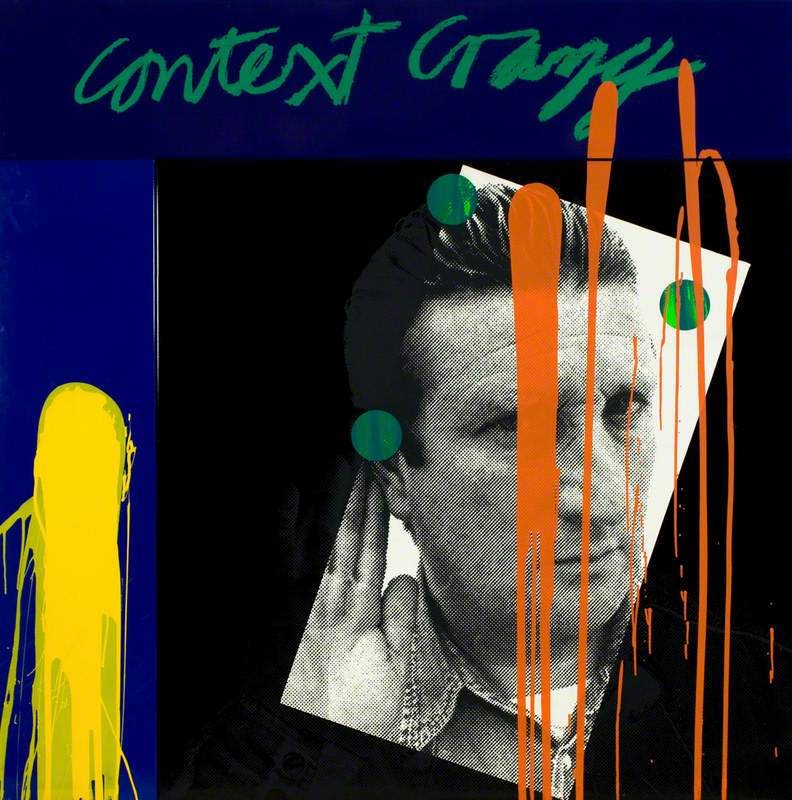

A champion and avid collector of the artist, Andy McCluskey of the beloved band Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark (OMD) has collaborated with Trent Art Gallery to assemble 21 works by Wade in his private collection. Once a visual artist before finding success in the music business, McCluskey's upbringing in the north, around Liverpool and Merseyside, resonates with the quiet, industrial vision of Wade. I spoke to the musician to find out more about his long-lasting passion for Wade.

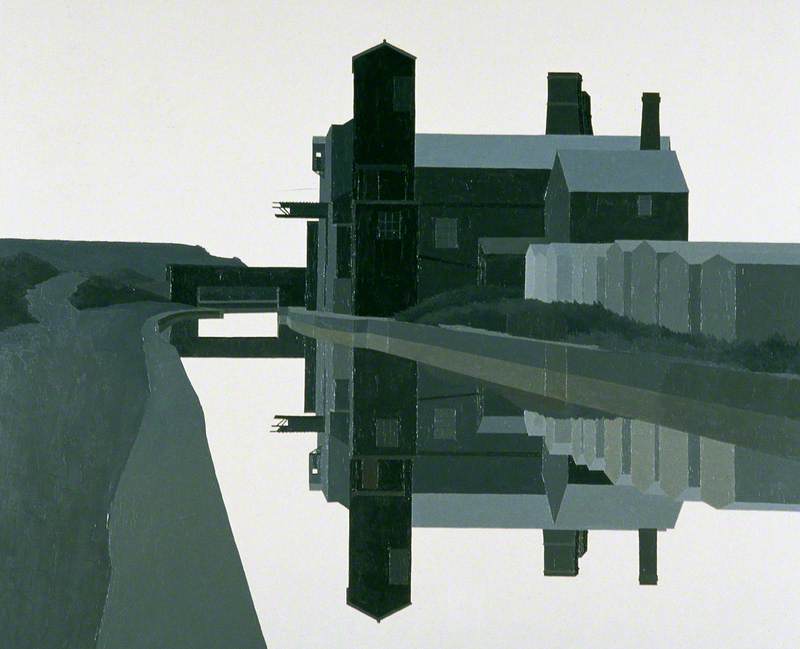

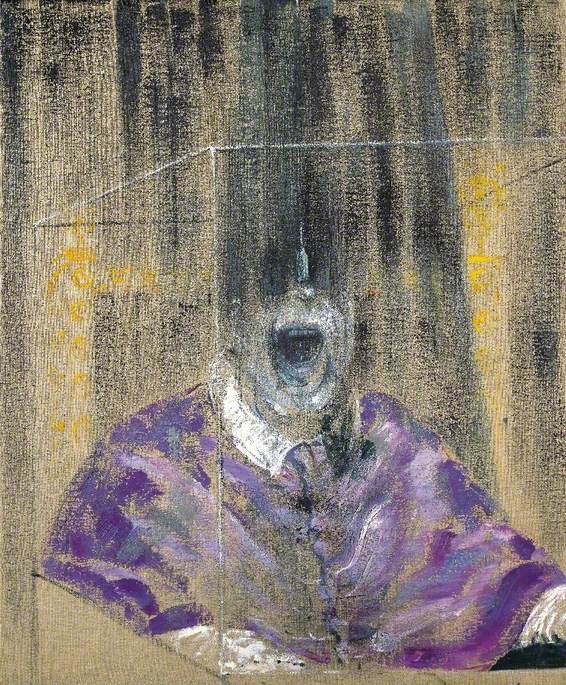

Pillars (Ravendale)

1972, oil on board, by Maurice Wade (1917–1991)

Lydia Figes, Art UK: When did you first come across the works of Maurice Wade?

Andy McCluskey: I saw his work for the first time at Clark Art Gallery, in Hale, south of Manchester. I had started collecting post-war 'Northern artists' by that point, and was looking through the gallery's website. I saw Pillars (Ravensdale) and initially thought it was an abstract. Not long after I went to the gallery to purchase something else, and that's when I saw the work in the flesh. It stopped me in my tracks. It was clear that it wasn't an abstract at all; the composition contained chimneys pillars reflected in the cold waters of the canal. I was absolutely captivated and that was the beginning of my love affair.

Lydia: His works are ostensibly quite melancholic, perhaps even bleak. Do you see them in this way, or is there something more uplifting upon further reflection?

Andy: Initially, yes, that's the first impression people usually get. One of the problems is that photographing the paintings is notoriously difficult. His works were all painted with palette knives so you can't capture the multi-faceted quality of the painting's surface. In real life, there is an interesting play of light that bounces of the surface when you move in front of the painting. You can see the depth of colour and texture.

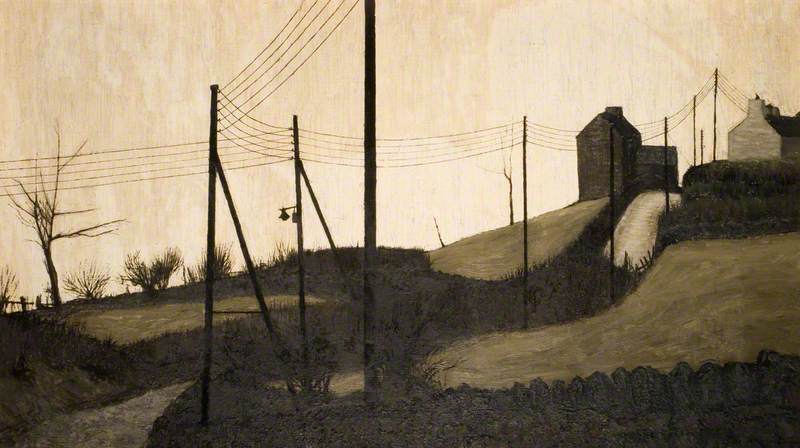

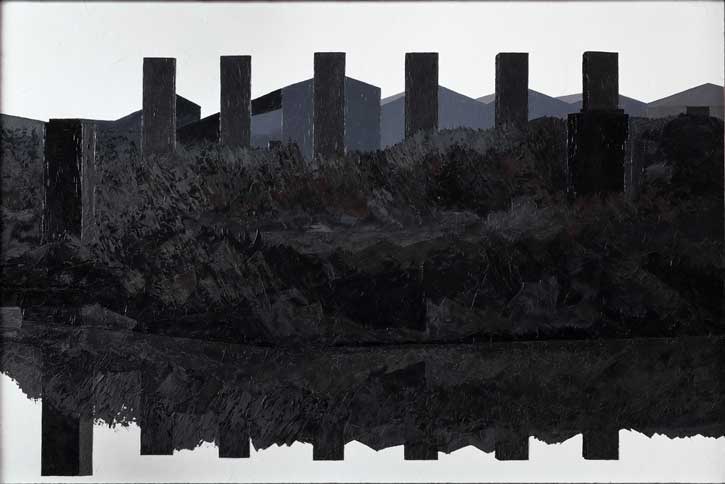

Burslem, Staffs Potteries

oil on board by Maurice Wade (1917–1991)

The works are largely urban, or 'post-urban' industrial landscapes. They are all monochrome and bereft of people – so yes this does convey a melancholic quality. At the same time, they are human constructs and, for me, are quite reassuring. But perhaps that resonates with the darkness in my own soul (ha). They have a tranquil quietude that is rare in a lot of paintings of industrial landscapes. He captures the scene in an unsentimental, reduced and modern way.

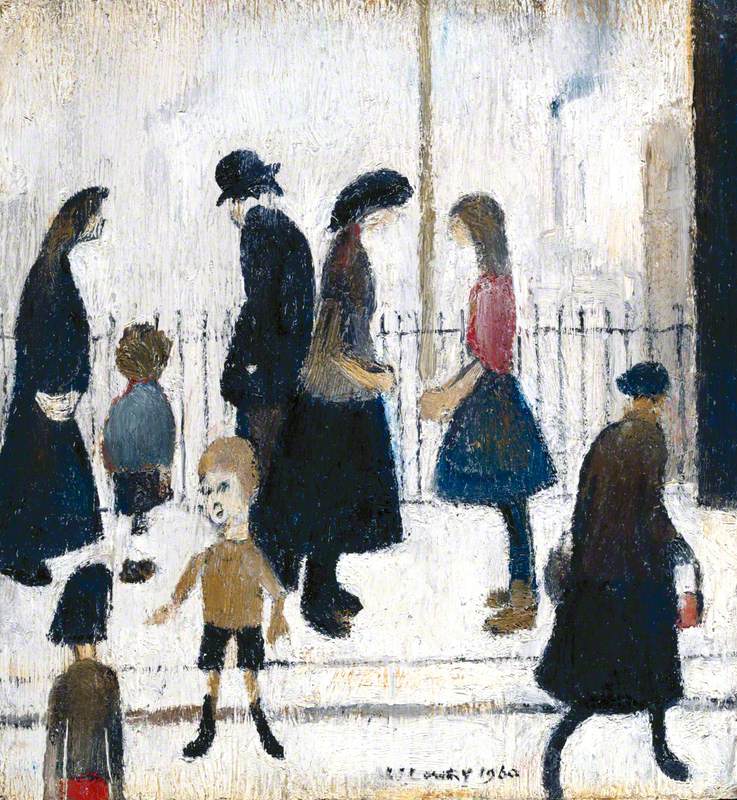

Lydia: Comparisons have been made between the paintings of Wade and L. S. Lowry, who also painted the industrial north. What do you think about these comparisons?

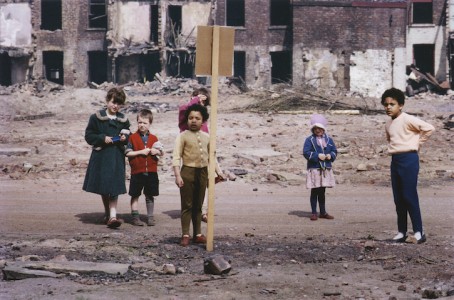

Andy: I don't think Wade's works are akin to Lowry's. Lowry is known for his naïve representation of people within the industrial landscape. There is a nostalgia and sentimentality in his works that you don't find in Wade's. For me, they are almost the antithesis of Lowry. They are certainly broody and melancholy, but they have a powerful crisp starkness to them which is unlike Lowry. Obviously they are still reflections of industrial landscapes, so yes there is a similarity there. I'm a boy from the Merseyside area, so I'm very familiar with how these landscapes appeared in the 1960s, and they resonate with me.

Clay Hills

1961, oil on board by Maurice Wade (1917–1991)

Lydia: He died in 1991, but did you ever get a chance to meet him?

Andy: No sadly he passed away before I started collecting. Curiously, we're still unable to unearth a photograph of him – and it's difficult to find people who knew him. He seems to have lived a very quiet life and kept to himself. I'm not sure how he would have dealt with people collecting his work, or being effusive with praise. I suspect he was a humble man. He was far removed from the extravagant bohemian lifestyle that many artists of that era experienced. He was probably a humble and ordinary man who created works that were extraordinary.

We know that he had a studio in a converted attic of his Victorian house, and all his paintings were created within 5 miles of where he lived. He was an art teacher until his retirement, and I don't think he sold enough works to support himself as a full-time artist.

Lydia: Have you already seen an increase in interest since the opening of the Trent Art show?

Andy: Yes. In fact, we're trying to track down missing paintings and create a comprehensive catalogue raisonnée. It's been great to see more people come forward since we've raised his profile, because we're able to locate his other works that are privately owned.

I own 21 of his works, but I'm aware that collecting is a rather selfish addiction (and I don't plan to sell any of my works). I want the public to be able to see his works too, I see it as a public duty. We're glad he's beginning to achieve the recognition that he deserves.

Tileries at Westport

1962, oil on board by Maurice Wade (1917–1991)

Lydia: Which works in your collection are your favourites?

Andy: My favourites are probably Tileries at Westport (1962). It's an oblique painting of the one I first saw, Pillars (Ravensdale). It's a remarkable composition. My other favourite is Bridges Over Canal II, which shows a canal tunnel with light coming through from the other side. It's a remarkable painting and we've used it for the cover of the accompanying exhibition publication.

Lydia: If you had the chance to time travel and ask him one question, what would you ask?

Andy: I think it's impossible to offer a verbal legitimisation of a subjective and intuitive process. But there's a part of me that would want to ask 'Do you understand the process by which you reduce these landscapes to simple slabs of colour and arrangement, and why does that resonate with you so much?' But then I also think, if someone asked me 'Why did you write Enola Gay?', I'd respond with a pretty lousy answer, something like 'it seemed a like a good idea at the time.'

More than anything else, I wish that he had the chance to know that people are championing his work again and that his paintings speak to another generation.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

'Maurice Wade, Silent Landscapes – The Andy McCluskey Collection' is on at Trent Art until 29th April 2022. The accompanying exhibition catalogue can be purchased on the Trent Art Gallery site.