As a former curator of sculpture, I became very intrigued by Andrew Grassie's pleasingly puzzling The Government Art Collection Sculpture Store. What are we being shown here?

The Government Art Collection Sculpture Store

2002

Andrew Grassie (b.1966)

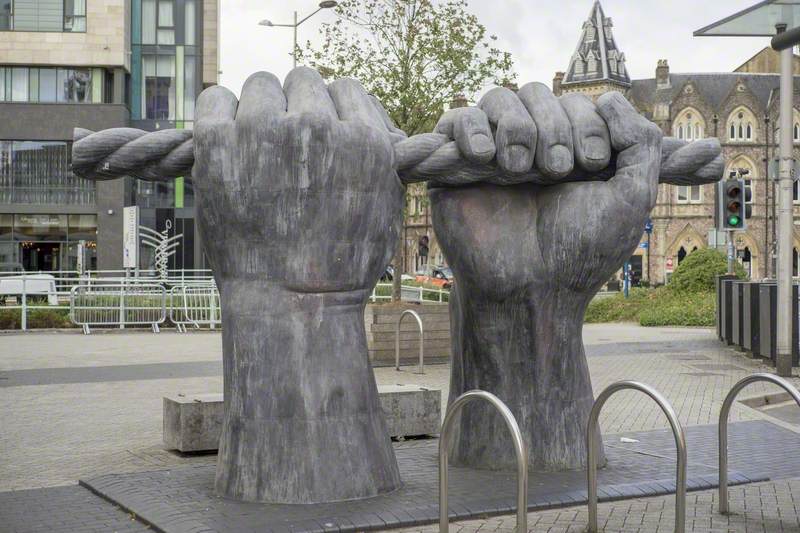

Sculpture stores in museums are usually quite densely packed, albeit in an orderly way. But Grassie's image presents us with an interior that is oddly spacious and, as we look at it more, represents a space that becomes steadily more ambiguous. Why are the sculptures still on their plinths? And why is Martin Creed's neon sculpture on the wall still illuminated?

Seen with a curator's eye, sculptures in store are inevitably assessed in terms of their future display potential but this potential is being more than hinted at here. We are being presented quite overtly with elements of a sculpture display (past or future?) within what purports to be a store, albeit a store with expensive parquet flooring. Is this perhaps a display space that has become a storage space? Or is it a store in which a curator has been trying out different types of plinth, as part of the process of formulating a new display?

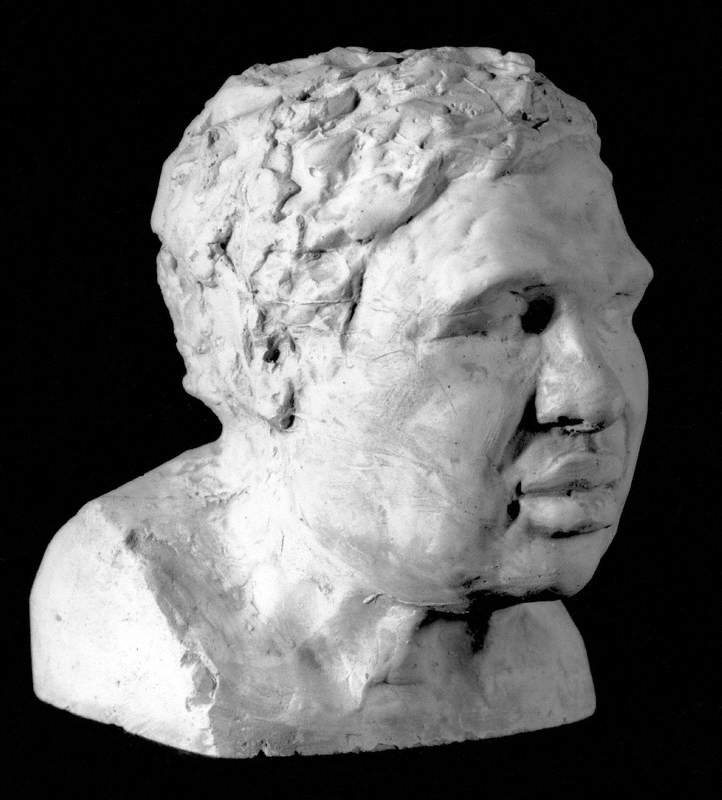

Plinths are being played with here, most obviously by placing Rachel Whiteread's maquette for the Fourth Plinth on its own (standard) plinth – an upturned plinth on a plinth set on a plinth – but also by the witty conceit of the plinth-like box alongside it and the contrast between the formulaic plinths, painted white, and the original coloured (scagliola or granite?) plinth below the bust of Beatrice glimpsed in the distance.

And what of the way in which different sculptural materials are related to each other here, with the foreground dominated by a bronze head?

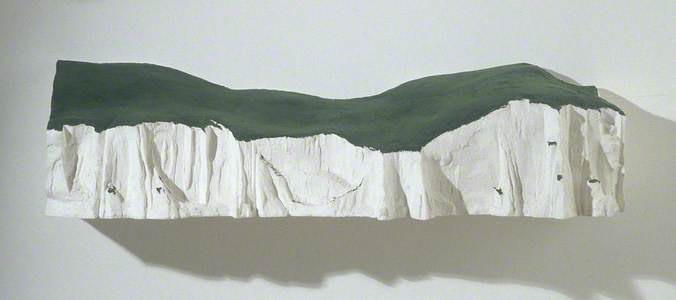

The play between storage and display that we are being teased with here is continued in the way that Tania Kovats' Blue Birds II, is shown partly enfolded in a sheet on a trolley, adjacent to the wall on which it will be shown but as yet in transit, so enhancing the ambiguity of the image.

At once carefully crafted and seemingly arbitrary, Grassie's image showing the store/display of sculpture taps into a long tradition of representing sculpture in painting. Sometimes this is done in a directly referential way and in other cases it involves a subtle play on the relationship between the two media. As in this case, the best examples leaving us puzzling about how each medium works. Not the least of pleasures afforded by a browse through Art UK's online collection is the discovery of how many ways in which sculpture has been used in painting and a recognition of the continuing fascination which sculpture has had for painters.

And you don't need to know anything about sculpture to enjoy these inventive conceits, just as this 'behind the scenes' view is hardly for sculpture curators alone, much as I, as one of them, might be intrigued by it.

Malcolm Baker, art historian and curator