On 12th January 2024, the film adaptation of Alasdair Gray's 1992 novel Poor Things was released to British audiences. Early critical responses have been hyperbolic, but excitement surrounding the film's release in Scotland has been tempered by some controversy.

This is because all references to Glasgow – Gray's home city, and the place where much of Poor Things was originally set – have been removed from the cinematic version. As Robin McKie writes in The Guardian, for many, 'it will be it be like watching The Lord of the Rings without Middle Earth or Titanic without the iceberg'.

Emma Stone as Bella Baxter in 'Poor Things'

This article does not wade headlong into that dispute. But I do want to point out that the frame narrative, within which the main events of Poor Things unfold, locates it even more squarely within Glasgow – by folding the story into the author's own biography.

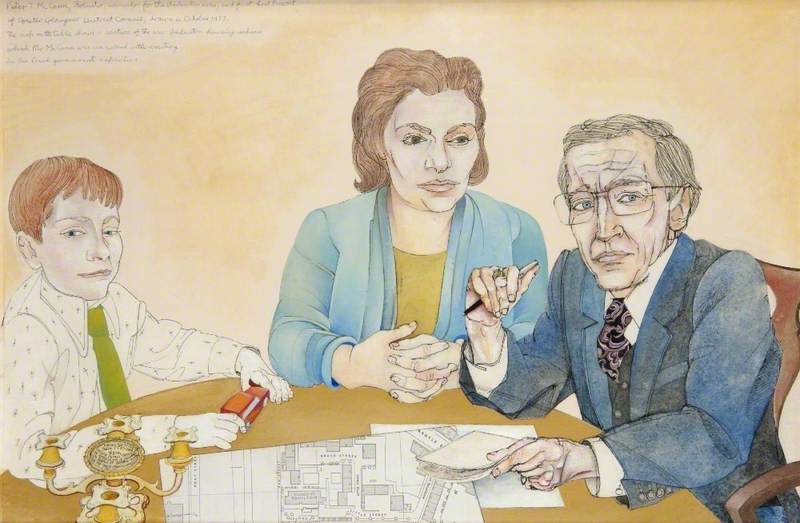

In the book's first-person introduction, Gray assures us that the tale shortly to be presented under the title 'Poor Things' (a gothic black comedy set in the 1880s) comprises a real memoir by a long-dead public health officer, found in a pile of discarded papers by a colleague of Gray's during his time as Artist Recorder for Glasgow in 1977.

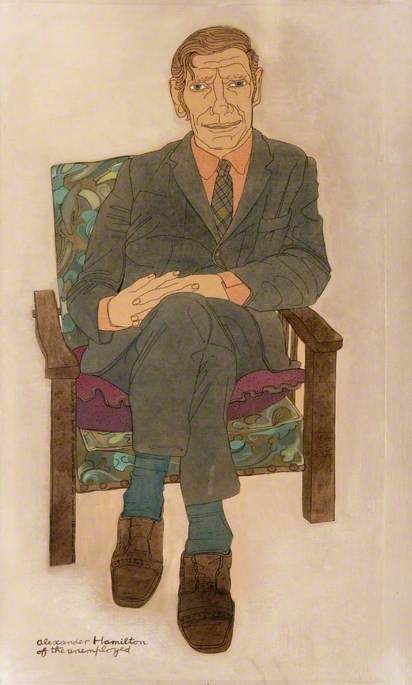

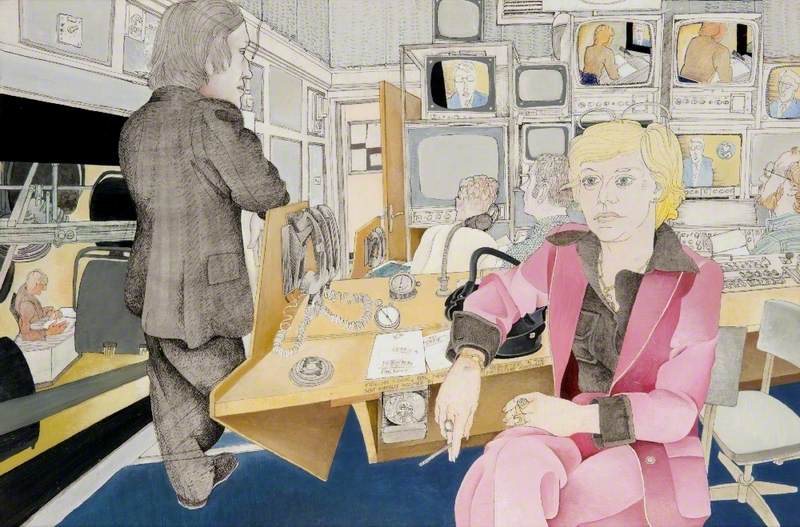

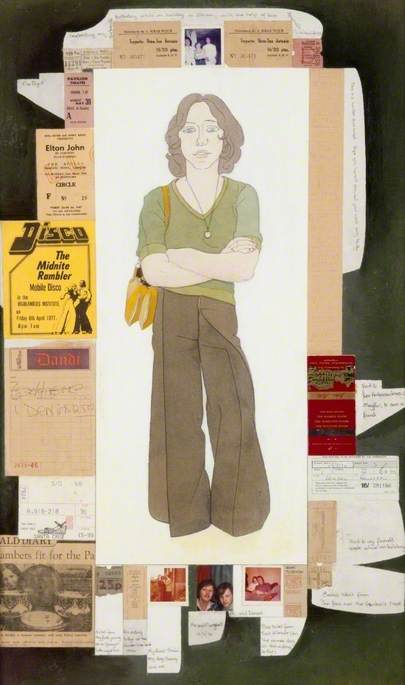

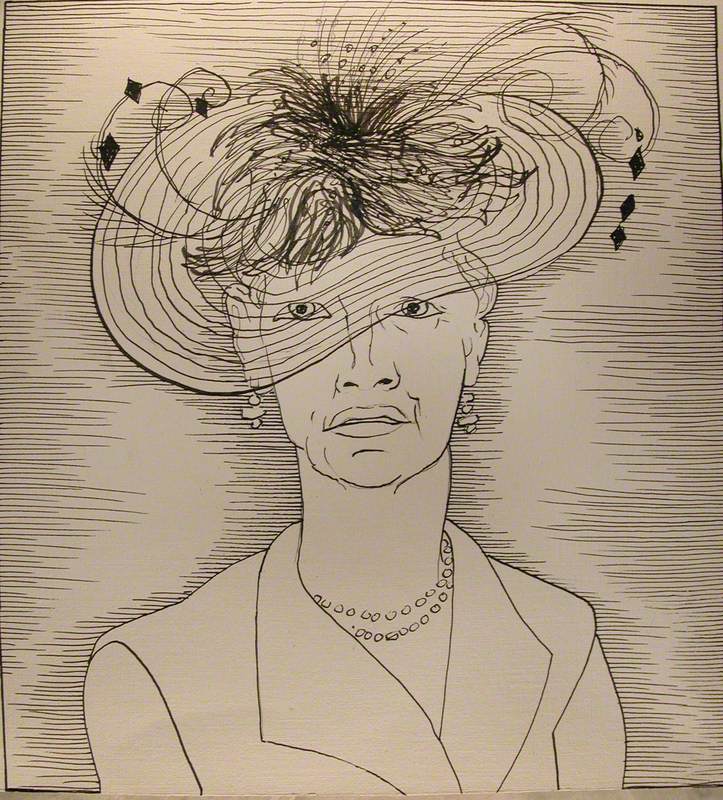

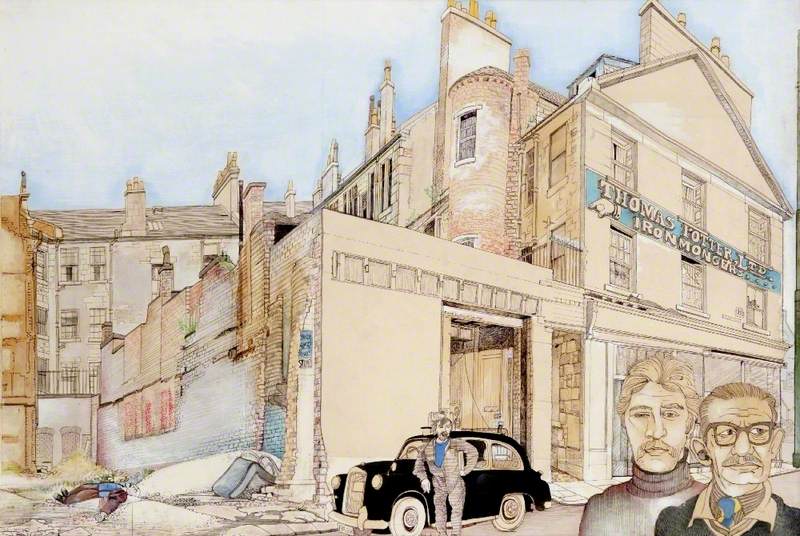

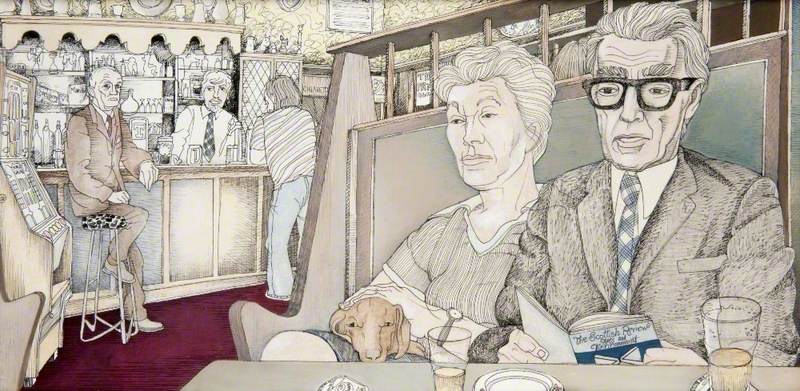

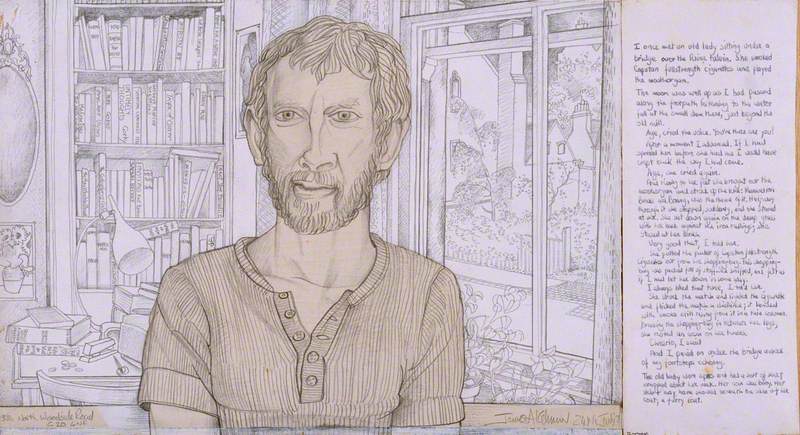

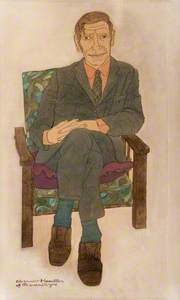

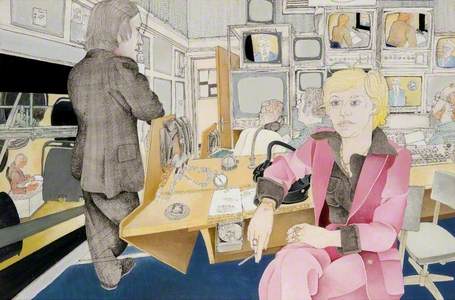

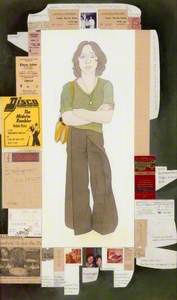

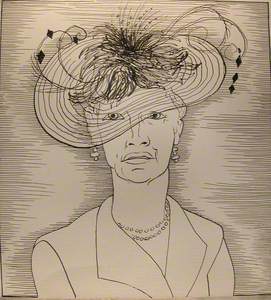

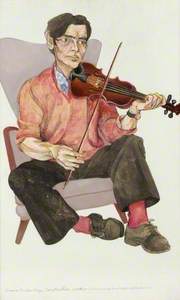

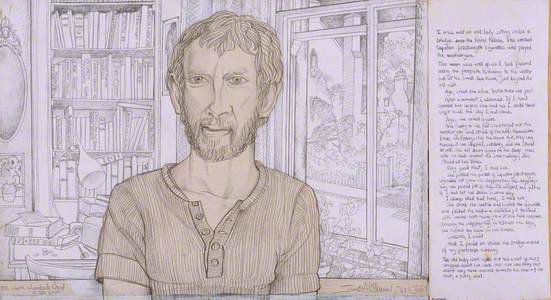

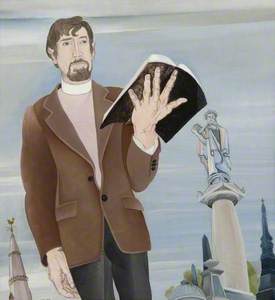

As Gray's biographer Rodge Glass notes, Gray's dream-role of Artist Recorder, based at the People's Palace museum on Glasgow Green, involved creating 'more than thirty portraits of contemporary Glaswegians and streetscapes of Glasgow's East End as it was being redeveloped... Some dealt with public figures, but most showed regular Glaswegians in their regular settings'.

The sequence includes newsreader Fidelma Cook and erstwhile Scots Makar Edwin Morgan, alongside Simon McGinlay, a construction worker, Frances Gordon, a Glasgow teenager and others.

There are panoramic street scenes and cityscapes, too, such as End of Arcadia Street, described by the art critic Cordelia Oliver as a 'feat of observation of the essential character of place and posterity. Most artists with the necessary sleight of hand to perform this feat (create the wide-angle perspective of the work) would lack the empathetic imagination to endow it with this quality of life'.

Why the segue to these 1977 portrait pieces? Partly because they make up the bulk of the work by Alasdair Gray that is in public collections, and are here on Art UK. But also because, like the details of the frame narrative just described, these pieces show the inextricable connection between Gray's art, his everyday life and the location in which both unfolded.

This might give viewers of the new Poor Things film pause for thought, even as they relish director Yorgos Lanthimos's new staging of events in a grimy, steampunk London, featuring Emma Stone, Willem Dafoe, Ramy Youssef and Mark Ruffalo.

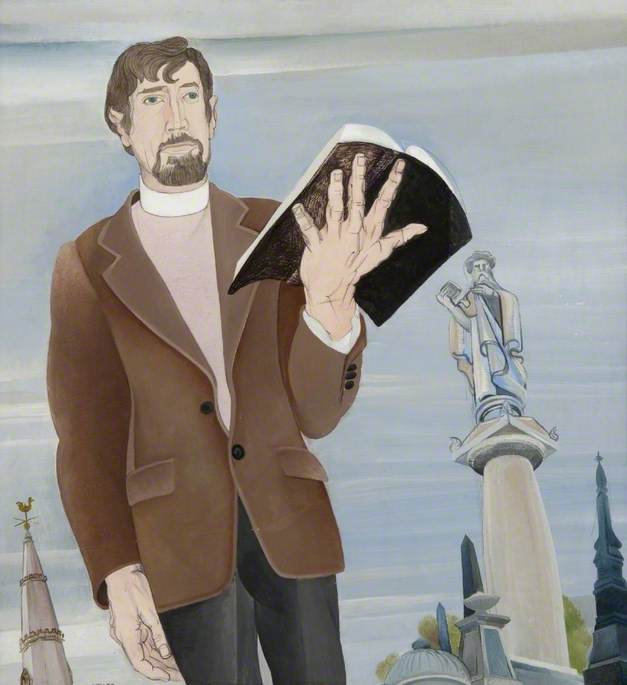

Alasdair Gray is sometimes referred to with ironic understatement as a 'jack of all trades'. In fact, he is one of the great creative polymaths of modern Scottish history. Raised in Riddrie, a working-class north-Glasgow suburb, he studied at Glasgow School of Art from 1952 to 1957. And, as his fellow student Ian McCulloch put it, he 'seemed to come fully formed'.

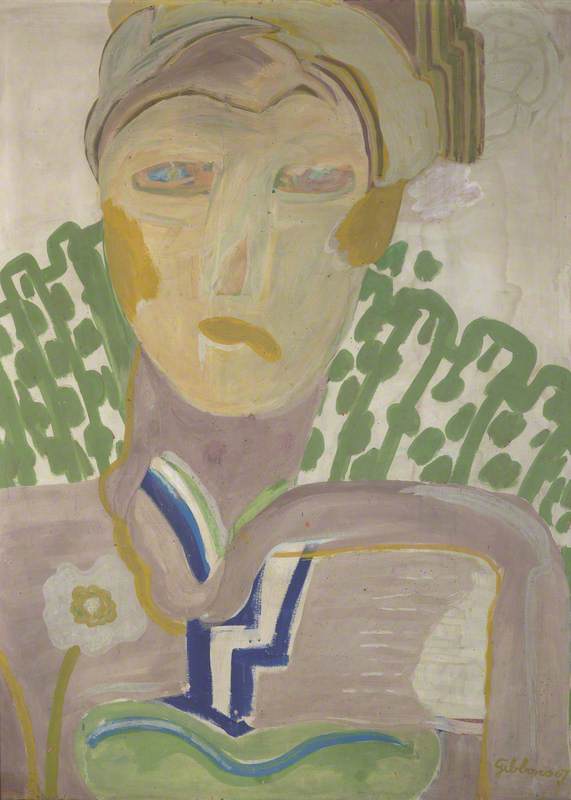

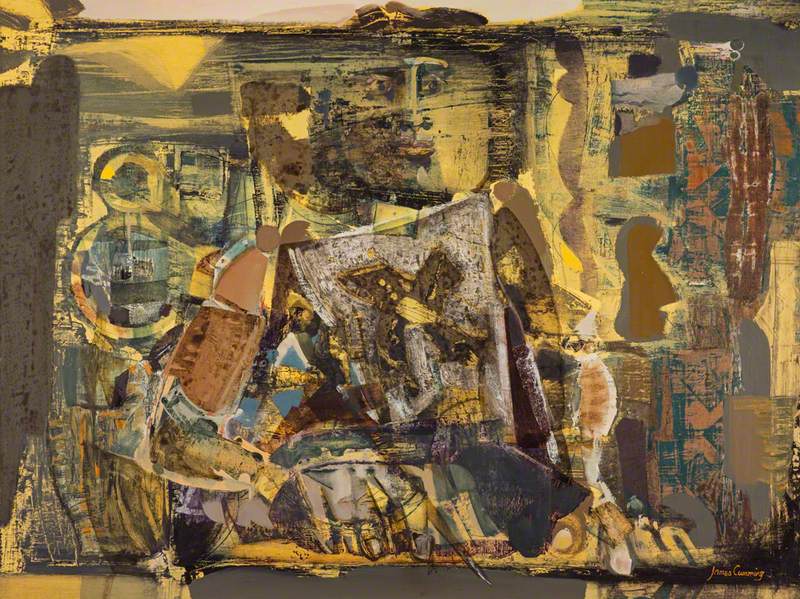

The lavishly illustrated visual primer A Life in Pictures (2010) includes pieces dating back as far as 1950, which show the same bold outlines, colour planes and feverish intensity of detail (always figurative, even when the scenes picked out are surreal) that characterised Gray's visual practice for the next seven decades.

Similarly, his literary masterwork Lanark, eventually published in 1981, was created across 30 years, starting during his adolescence, at which stage much of the imaginative architecture was established.

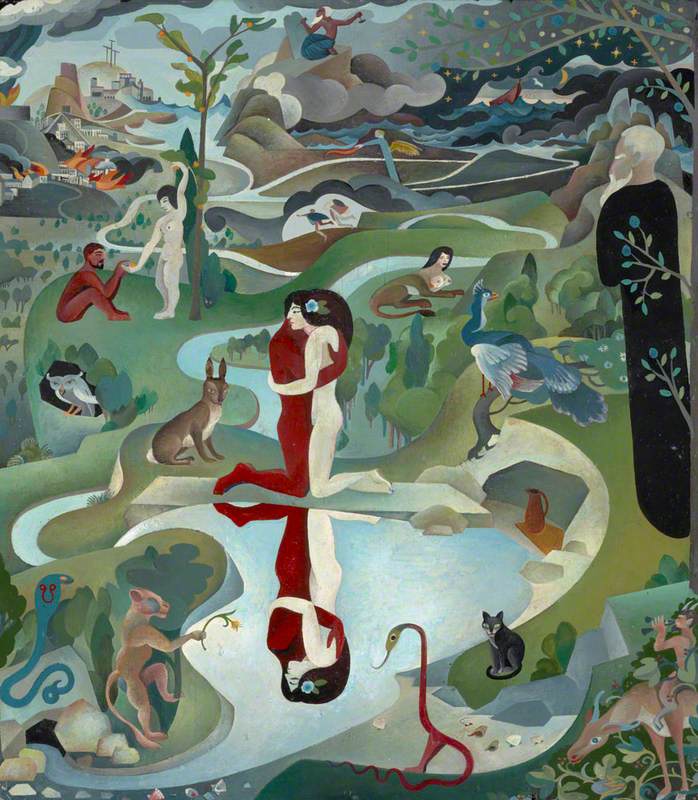

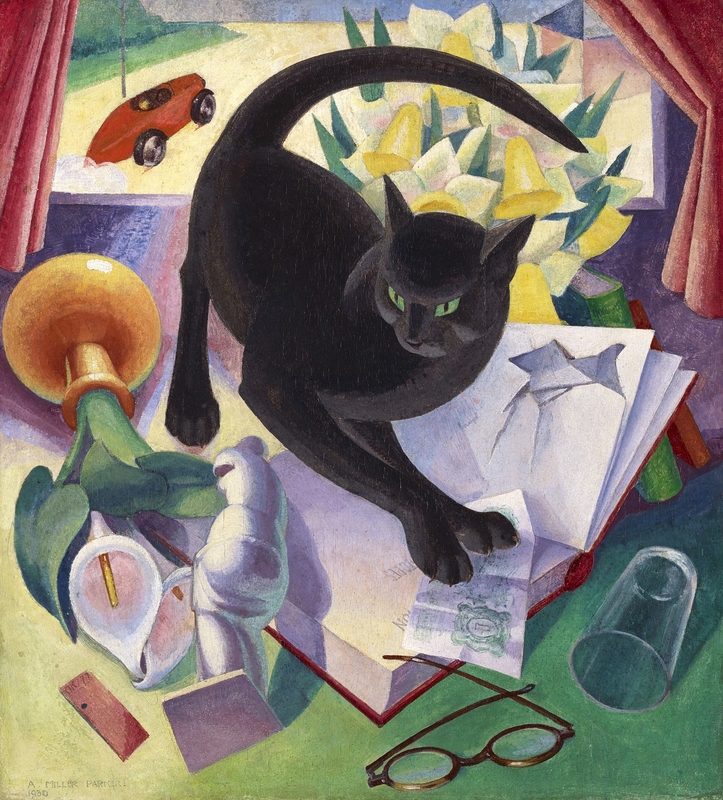

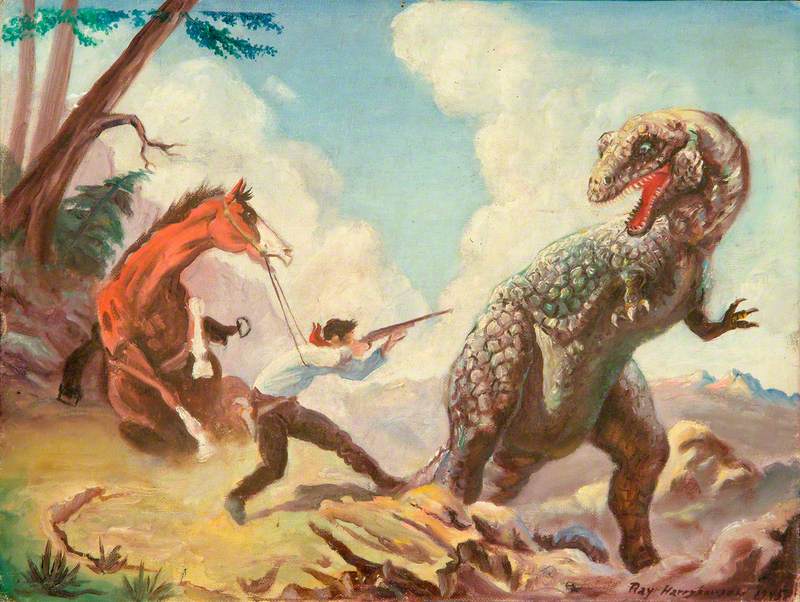

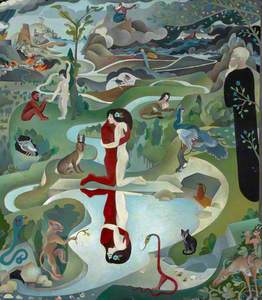

Crucially, Gray was an artist and writer to equal extent. Influenced by the languid, louche figures of Aubrey Beardsley and the mysticism and mythology of William Blake, Gray illustrated his own books with the scenes, people and situations encountered therein: from kitchen-sink dramas to the fantastical spectacle of Lanark, half of which unfolds in a nightmare-version of Glasgow plagued by mystery disease and perpetual darkness.

Gray also produced stand-alone paintings and, most spectacularly, murals, which now adorn many public and private spaces across Glasgow. These public artworks show realistic or otherwordly scenarios generally related in some way to history, religion or politics, often those of the painter's native country – Gray was a lifelong Scottish nationalist, as well as a socialist.

Eden and After, below, a work reminiscent of Henri Rousseau, is based on a section of one of his most famous murals – famous partly because of the fictionalised account of its creation in Lanark – a biblical sequence made for Greenhead Church in Glasgow, which was demolished shortly after the piece's completion.

Poor Things was Gray's next great literary success after Lanark, and might be described as a feminist reworking of Frankenstein. Set in late nineteenth-century Glasgow, it concerns an earnest young doctor, Archibald McCandless, who becomes convinced that his friend, the huge, hulking but benign Dr Godwin Baxter, has reanimated the corpse of a woman, inserting the brain of her unborn baby into her skull to create an entirely new human being.

Willem Dafoe as Dr Godwin Baxter in 'Poor Things'

This is Bella Baxter, whose childlike intensity, voracious appetite for learning and lack of social or sexual humility – of the sort expected of Victorian ladies – make her more than a match for the male characters in the novel, and drive much of the plot.

Emma Stone as Bella Baxter in 'Poor Things'

Back now to our frame narrative. We learn about Bella and Archibald's life together – they eventually marry – through what is presented as a self-published story by the latter, of which only one copy was ever made. Gray's introduction to Poor Things tells us that McCandless's book was found on the street one day by the author's colleague at the People's Palace, the curator and researcher Michael Donnelly.

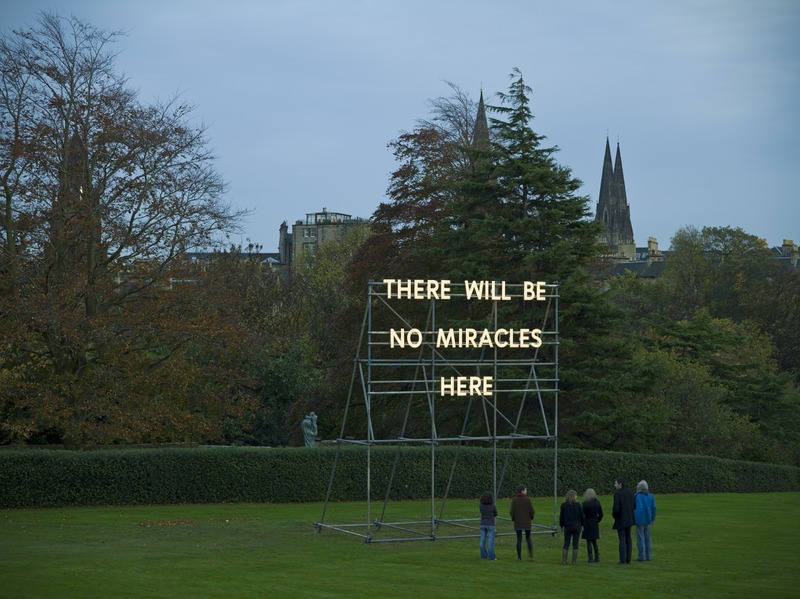

The introduction is set in 1977, the year of Gray's employment as Artist Recorder, and a time when much of Glasgow's architectural heritage (and with it the city's cultural memory) was being erased to make way for 'multistorey housing blocks and an ever-expanding motorway system'.

One morning, while 'passing through the city centre ... Michael Donnelly saw a heap of old-fashioned box files on the edge of a pavement, obviously placed there for the Cleansing Department to collect and destroy'.

The pile includes McCandless's self-funded volume, which, Gray tells his readers, Donnelly has passed on to him, and which he is now presenting to us under the new title Poor Things.

Gray uses the frame narrative to present a lurid historical yarn, but also undermines our faith in its truthfulness – a familiar trick from gothic and detective fiction, deliberately linking his tall tale with the writings of predecessors such as Mary Shelley, James Hogg, Edgar Allan Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle.

But the significant point here is that the frame narrative overlaps with Gray's real life. Michael Donnelly was a real person, assistant curator at the People's Palace where, in 1977, Gray was really working under Elspeth King, curator of social history, who is also name-checked in the opening pages.

As in so much of Gray's writing, it becomes hard to fix the point where fiction and biography meet. As Glass puts it, Gray 'openly uses and abuses autobiography in his work', indicating that Poor Things is, in part, a book about Gray's own life.

And if it is a book about Gray, it is also about the place that shaped him as a person and artist – Glasgow – and about his desire to preserve a multifaceted memory of that place. This includes both the contemporary aspects of the city captured through his portraits and street scenes made as Artist Recorder, and those elements disappearing, metaphorically or literally, under the tower blocks and motorways: the Victorian interiors, civic gardens and fusty old medical schools evoked in the main narrative of Poor Things.

Rodge Glass has reacted in sanguine fashion to the excising of Glasgow from the Golden Globe-winning adaptation of Poor Things. 'If 1% of those who see Poor Things go on to read the book,' McKie quotes him as saying, 'that means thousands of people who might have known little about Glasgow or Gray will have their eyes opened about the city and the man. That has got to be a good thing.'

Some of these new fans will no doubt find the brilliant interactive guide to the novel recently created by the Alasdair Gray Archive. Perhaps some will also come to realise the umbilical knot between artist and locale that define Gray's art and secure its value: that the local, in this case, is truly the universal.

Greg Thomas, freelance writer

This content was supported by Creative Scotland

Further reading

Rodge Glass, Alasdair Gray: A Secretary's Biography, Bloomsbury, 2008

Alasdair Gray, Lanark, Canongate, 1981

Alasdair Gray, A Life in Pictures, Canongate, 2010

Alasdair Gray, Poor Things, Bloomsbury, 1992

Cordelia Oliver, 'Alasdair Gray: Visual Artist' in The Arts of Alasdair Gray, by Robert Crawford and Thom Nairn (ed.), Edinburgh University Press, 1991