'Works of Mercy' and 'Acts of Mercy' are phrases that are familiar to many from religious literature. The works or acts in question are described in the Bible (mainly Matthew 25: 35–40) as feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, clothing the naked, visiting prisoners, sheltering strangers, visiting the sick, and burying the dead. They are also the subject of a number of paintings, from the fifteenth to the twentieth century.

Many such paintings were created as incitements to acts of charity like those depicted. Others commemorate such acts already performed, for instance through the founding of almshouses. They represent what are now called social services, but at a time when such services originated from religious teachings – the doctrine of Christian charity – rather than being performed for secular reasons alone.

The Wellcome Library’s collections of paintings, drawings, prints and photographs were created to document a particular range of subjects in all places and at all times, and the 'Works of Mercy' is one of those subjects. The Library already had a number of pictures on this theme when it acquired in 2009 four large paintings called Acts of Mercy by Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927).

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

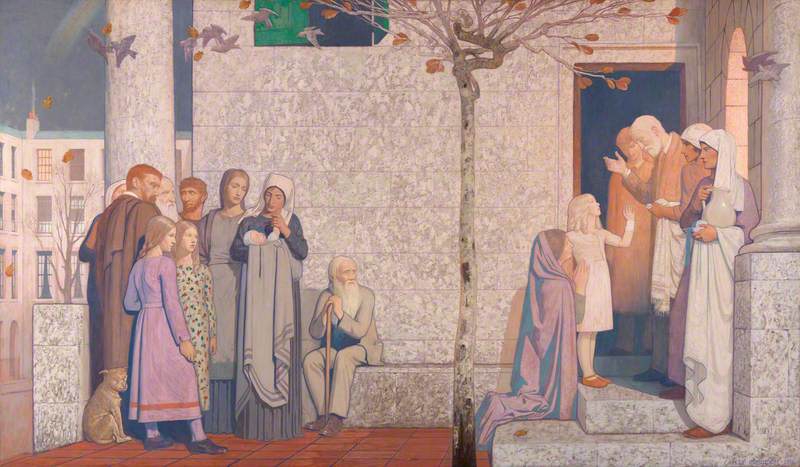

Men, Women and Girls Standing in a Group Outside a Hospital 1916

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

Wellcome Collection

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

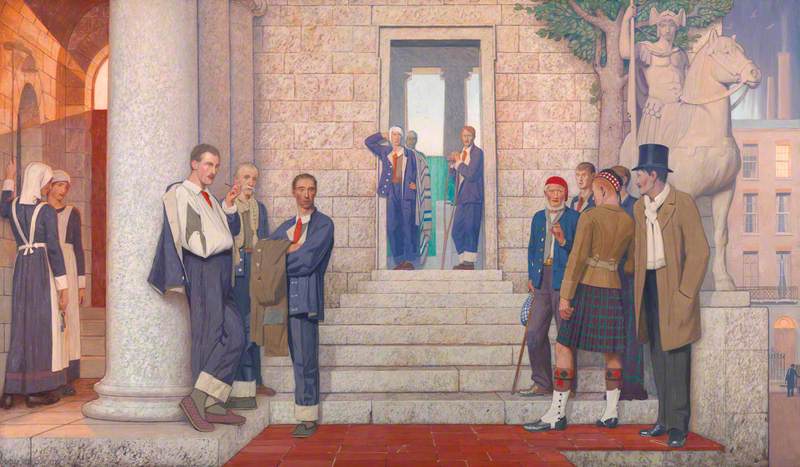

Wounded and Sick Men Gathered Outside a Hospital 1920

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

Wellcome CollectionCayley Robinson's four paintings were originally commissioned to hang in the entrance hall of the Middlesex Hospital in London, where they inspired thousands of patients and staff members over the years.

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

Orphan Girls Entering the Refectory of a Hospital 1915

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

Wellcome Collection

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

Orphan Girls in the Refectory of a Hospital, Proceeding to Their Place at the Table c.1915

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

Wellcome CollectionThe Art UK database brings the Cayley Robinson pictures together not only with other Wellcome Library paintings but also with paintings on the same theme in other collections. Until the Art UK database became available, it was very difficult to discover what other paintings of a particular subject existed elsewhere.

One finds the name of the Antwerp painter Frans Francken II (1581–1642) associated with many of these paintings. A composition by him in which all the seven ‘Works of Mercy’ are represented in one scene seems to have been especially popular: Art UK reveals versions at Fairfax House in York, Manchester Art Gallery and the Wellcome Library.

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: Christ among the Doctors c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk CastleThey all show on one side a man handing out loaves of bread, and a woman with a baby among the recipients. There are however many differences in detail between the three versions which would be worth studying and explaining. Such paintings could well have hung in a chapel, town hall or charitable institution as a reminder of the Christian message.

However it is another work associated with Francken that I was most interested to find in the Art UK database: a set of seven small paintings on copper set into a magnificent piece of furniture, the Chirk Cabinet, at Chirk Castle in Wrexham, Denbighshire.

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: Christ and the Canaanite Woman c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk Castle

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: Christ and the Centurion c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk Castle

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: Christ and the Woman of Samaria c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk CastleWhen the doors of the cabinet are opened, the panels inside feature scenes from the life of Christ.

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: Christ Healing the Man Blind from Birth c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk Castle

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: 'Suffer the little children to come unto me' c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk Castle

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: The Seven Acts of Mercy, 'To feed the hungry' c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk CastleAlongside these, there are seven paintings that show the seven 'Works of Mercy'.

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: The Seven Acts of Mercy, 'To give drink to the thirsty' c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk Castle

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: The Seven Acts of Mercy, 'To clothe the naked' c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk Castle

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: The Seven Acts of Mercy, 'To visit the prisoner' c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk CastleThough I vaguely remembered the publicity around the cabinet’s acquisition by the National Trust over 20 years ago, I had forgotten that the paintings show the 'Works of Mercy'.

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: The Seven Acts of Mercy, 'To shelter the stranger' c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk Castle

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: The Seven Acts of Mercy, 'To visit the sick' c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk CastleIt is understandable that paintings of this subject might have hung in a hospital (like the Cayley Robinson quartet) or an almshouse, but why would it be used in a cabinet luxuriously crafted from carved ebony with tortoise-shell inlays and wrought silver mounts? Surely the extravagant sums involved in its creation could have been better spent on charitable works themselves?

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Chirk Cabinet: The Seven Acts of Mercy, 'To bury the dead' c.1640–1650

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) (studio of)

National Trust, Chirk CastleThe answer may lie in the traditional provenance given to the Chirk Cabinet. It is reputed to have been given by King Charles II to Sir Thomas Myddelton (1586–1666) in 1661 in thanks for his role in the Restoration of the Monarchy. Surprising though it may be in retrospect, the future King Charles II had been on the receiving end of works of mercy. He had been a refugee in the English Civil War, and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography sums up his precarious life in France thus: 'Charles and his court led a wretched existence of poverty and enforced idleness, relying on a pension the queen mother received from the French government, and occasional donations from supporters in England.'

While Charles himself was languishing in poverty and exile, and Britain was still a Commonwealth, Myddelton had risked all by declaring Charles king. What more suitable gift could there be to a man who had given such succour at a moment of need?

William Schupbach, Librarian, Iconographic Collections, Wellcome Library