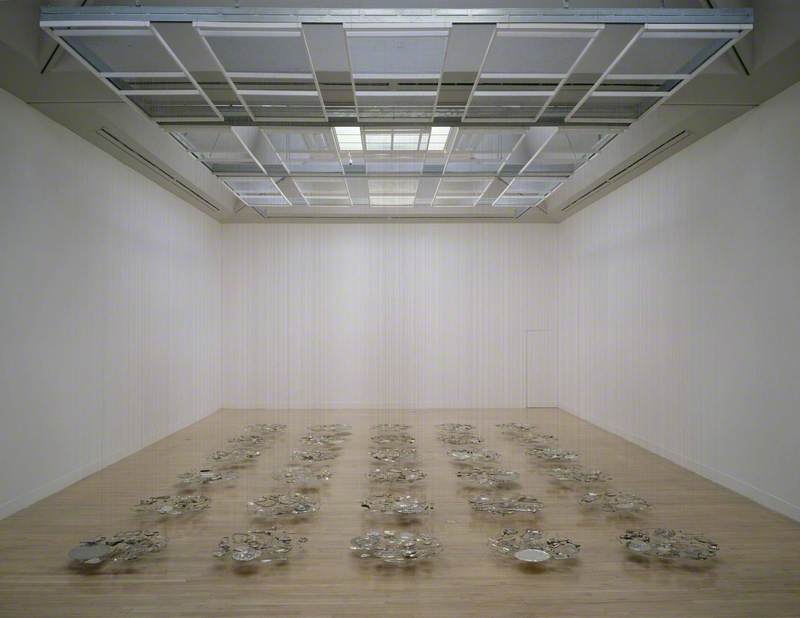

Cornelia Parker's new installation Island, created especially for her major retrospective at Tate Britain, features floor tiles the artist acquired from the Houses of Parliament when she was official General Election artist in 2017. Once situated in the corridors of power between the Commons and the Lords, the tiles are now suspended beneath a greenhouse, the glass panes of which are painted with chalk from the White Cliffs of Dover.

Installation view of 'Island'

2022, installation by Cornelia Parker

An obvious comment on Brexit and illustrative of Parker's concern for an England that no longer looks outward, the work also reveals the artist's use of found objects and wider interest in politics, identity and instability.

Across 40 years, the Turner Prize-shortlisted artist has also made sense of the world by treating objects with what she has termed 'cartoon violence', often reconfiguring our understanding of traditional sculpture in the process.

Installation view of 'Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View'

2021, installation by Cornelia Parker

Perhaps the most famous example of this is the early work Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991), in which Parker collaborated with the British Army to blow up a garden shed filled with soft toys, gardening tools and charity shop finds. Suspending the remaining parts from the ceiling, as if caught in the moment of destruction, lends the work a vulnerable quality, while its fragmentary composition distances it from solid sculpture. That the work references the era's IRA explosions provides an unnerving political context.

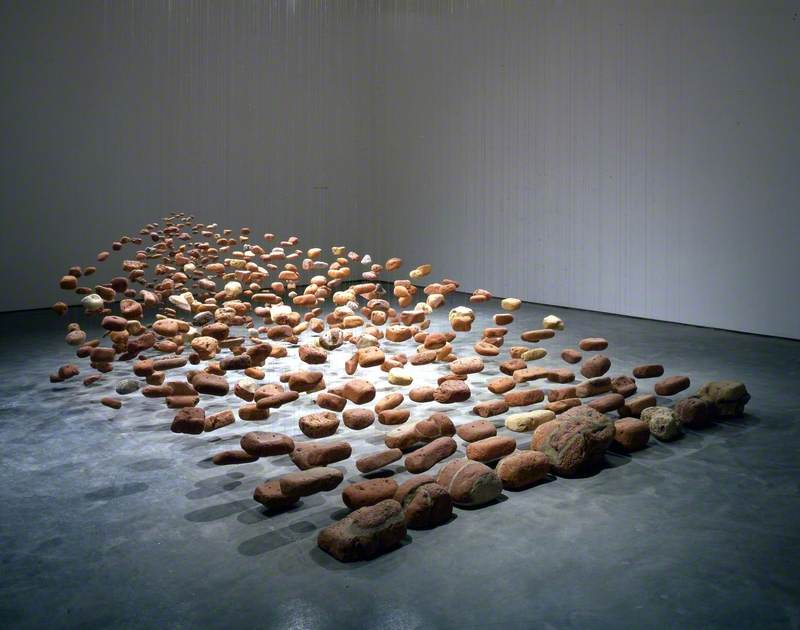

For Thirty Pieces of Silver (1988–89) Parker gathered hundreds of silver-plated objects – cutlery, candlesticks, musical instruments – and had them crushed by a steamroller, flattening both the materials' commemorative functions and class associations.

By suspending them from the floor in groups of 30 (a reference to Judas and reflective of Parker's Catholic upbringing) the objects convey a weightlessness that seems at odds with their once-solid forms. As with Cold Dark Matter, however, Parker's act of destruction allows for the creation of something new.

Since then, Parker has gone on to create a range of suspended works, reflecting her interest in gravity. In works such as Breathless (2001), in which familiar objects are transformed through suspension, she used disused brass instruments to comment on a fading form of 'Britishness'. In another, Subconscious of a Monument (2005), she hung soil fragments extracted from beneath the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

Early pieces reference the White Cliffs of Dover, as seen in Neither From Nor Towards (1992) or Inhaled Cliffs (1996), both of which evoke Parker's interest in forms of patriotism attached to this quintessentially British landmark. The former was made with beachcombed house bricks that fell from the cliffs and into the sea, unlike Object that Fell off the White Cliffs of Dover (1992), for which Parker herself orchestrated the objects' fall, playfully and violently throwing items over the cliff edge so that they emerged dented and scarred with the residue of chalk.

If acts of violence are a recurring theme in Parker's work, so too is an interest in dangerous objects such as guns and bullets. Embryo Firearms (1995) emerged after a visit to the Colt factory in Connecticut where Parker was fascinated by the first stage of gun production, before the object becomes a literal firearm.

The nine-metre sculpture of a gun in Landscape with Gun and Tree, shown at Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, in 2010, comically blows up the weapon depicted in Thomas Gainsborough's eighteenth-century portrait Mr and Mrs Andrews.

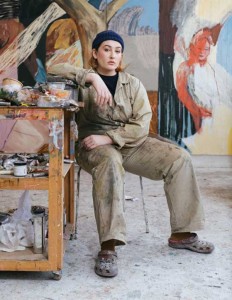

Parker has spoken about how her destructive creative urges were inspired by her childhood love of cartoon deaths – Tom and Jerry getting hurt only to be resurrected. Born in 1956 in Cheshire, the middle of three girls, Parker was brought up by a domineering father and a German mother who was later diagnosed with schizophrenia. She spent a year at Gloucester College of Art and Design and then Wolverhampton Polytechnic, before completing an MFA at Reading University and moving to London in the mid-1980s. Her first solo exhibition took place at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, in 1988.

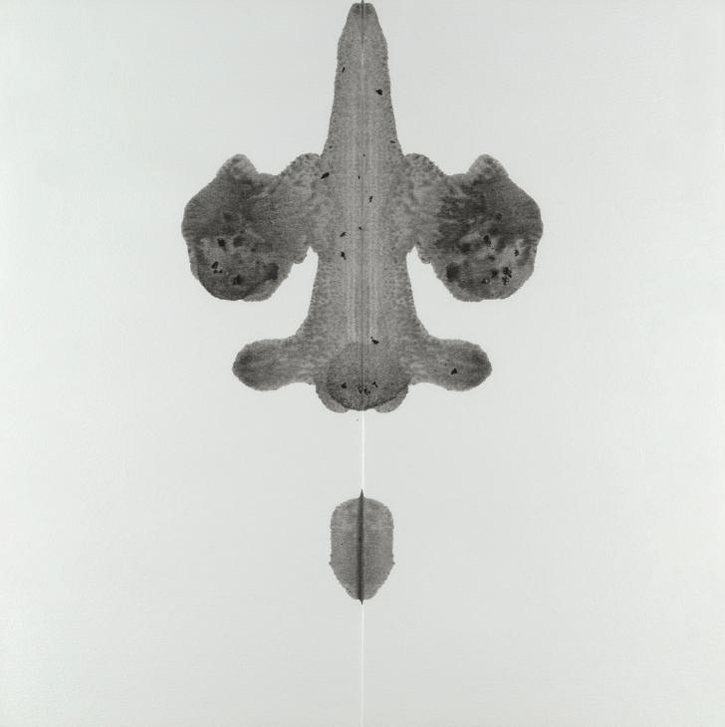

Pornographic Drawing

1996, ferric oxide on paper by Cornelia Parker

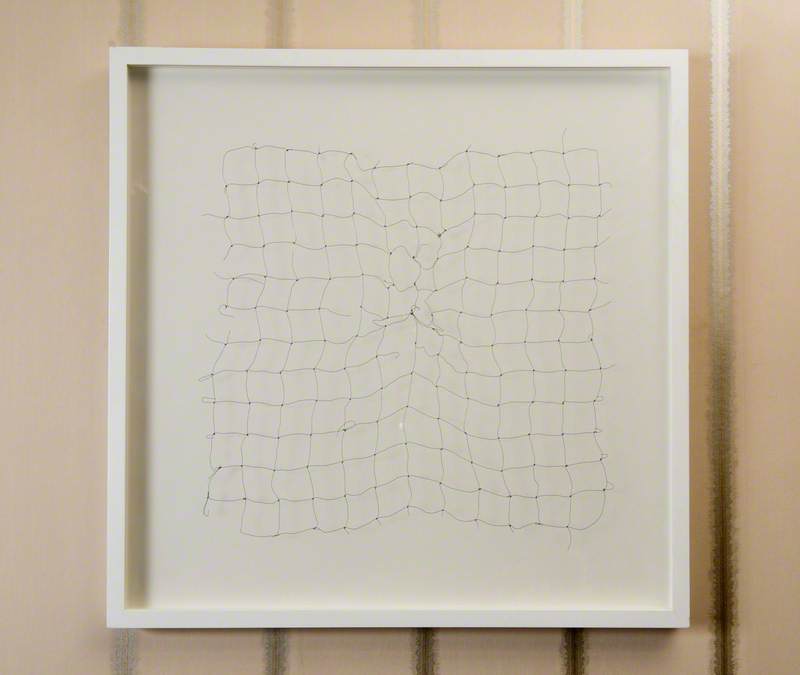

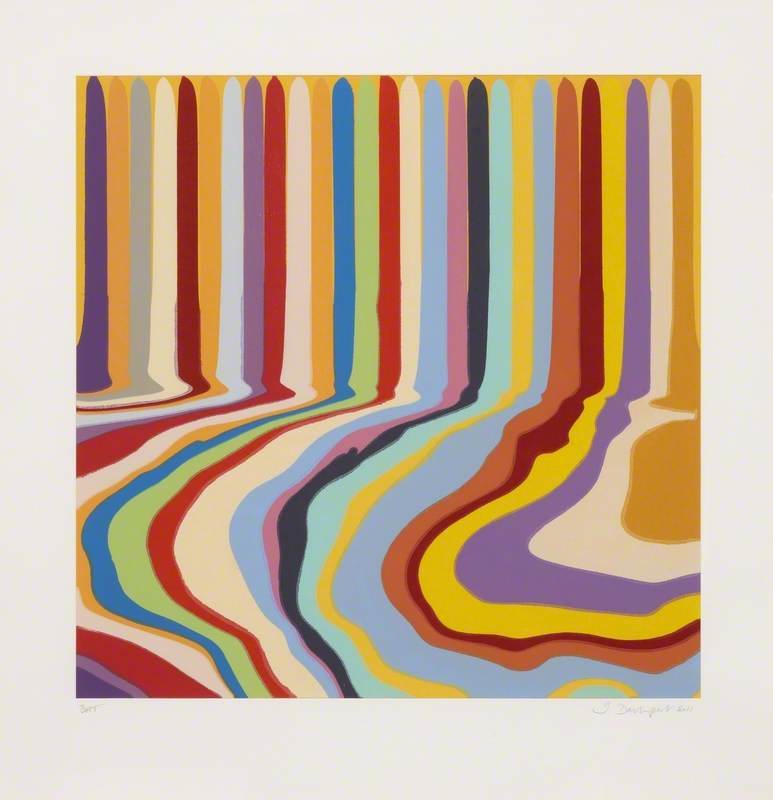

As critic Jo Applin writes in the catalogue accompanying the Tate exhibition, Parker 'is an artist who deals primarily in abstraction, despite the fact her work is made from recognisable objects'. This act of breaking something down can be seen in her Pornographic Drawings (1996–2005), made using the ferric oxide from chopped-up pornographic videos to create an ink then used to make Rorschach prints. Similarly, her series of Bullet Drawings use melted-down bullet lead drawn into wire in gridded works (a nod to Minimalism) that neutralise a violent object.

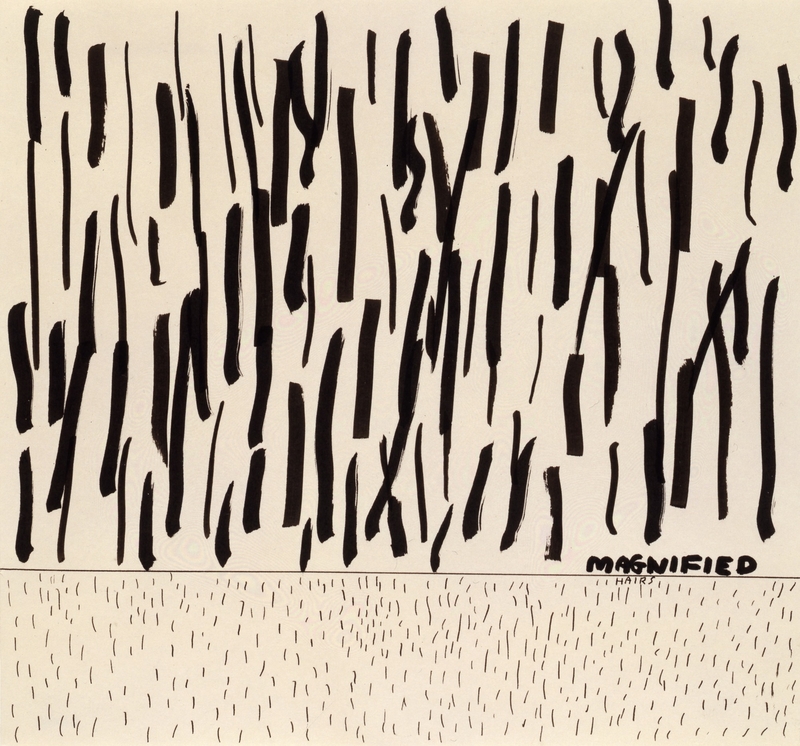

This idea of abstraction also extends to the works Parker has made about historical figures. Feather from Freud's Pillow (1997) is a screenprint featuring a single feather from a pillow found on the psychoanalyst's couch. Likewise, Brontean Abstracts (2006) zooms in on the seemingly inconsequential – ink blots, pin pricks and hair samples – to move beyond the myths surrounding such monumental literary figures.

Brontëan Abstract

2006, photograph by Cornelia Parker

Parker's use of the feather from Freud's couch emerged from her earlier work The Maybe, shown at the Serpentine Gallery in 1995, in which she collaborated with the actress Tilda Swinton, who lay like a saint in a glass vitrine surrounded by a variety of found 'relics'. These included a pillow from Freud's couch, Queen Victoria's stocking and Charles Dickens' quill – figures emblematic of shaping British society.

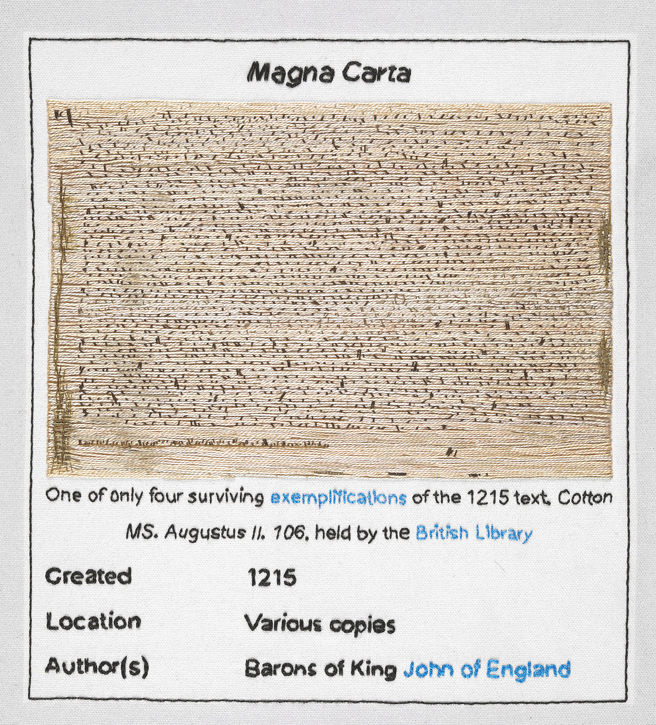

Magna Carta (detail)

2015, embroidery by Cornelia Parker

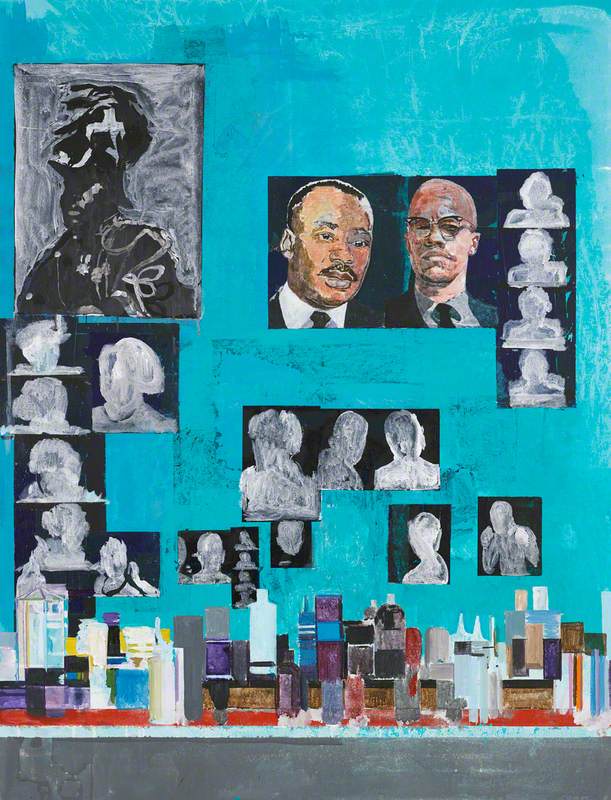

Parker's interest in political or social subjects – more explicit in recent years – can be seen in pieces such as War Room and Magna Carta, both from 2015. To celebrate the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, and in hommage of democracy, Parker created an ambitious 13-metre-long tapestry of the charter's Wikipedia page, enlisting prisoners to do the stitching alongside public figures such as Julian Assange, Edward Snowden and Alan Rusbridger.

War Room

2015, installation by Cornelia Parker

War Room, meanwhile, extends Parker's interest in absence by covering a room with the punched-out negatives from a poppy factory.

Parker began making films in 2007 with Chomskian Abstract (2007), a filmed conversation with political theorist Noam Chomsky in which the artist's questions are edited to create a deliberate silence. It reveals a concern with the climate emergency, for her now the most pressing political issue.

American Gothic (2016), filmed on her iPhone, is a four-screen installation showing footage of a Halloween parade in New York and a pro-Trump rally in front of Trump Tower. Filmed a few days before Trump was elected, it acts as a nightmarish vision of a world in flux.

American Gothic

2017, video still by Cornelia Parker

Her experience as the UK's official election artist in 2017, during which time she travelled the country filming rallies and manifesto campaigns, resulted in Left, Right and Centre, a short, eery film capturing an empty House of Commons using a mayhem-inducing drone. Election Abstract, also filmed on her iPhone (many of the images began life on the Instagram page she set up to document her experience), records a national mood at one moment in time.

Election Abstract

2018, video still by Cornelia Parker

The Tate exhibition, which gathers 100 works, includes three films that examine identity and nationhood. Flag was filmed in a factory in Cardiff and records the complex process of making a Union Jack, with the footage run backwards so that the flag is undone. In the same way that Island hints at Britain's instability and insularity, this new film points to Parker's interest in things falling apart, while also revealing the social critique that guides many of her quietly explosive works.

Imelda Barnard, freelance writer and editor

'Cornelia Parker' is at Tate Britain, London, until 16th October 2022