A spiritual system infusing medicine, cosmology, agriculture and arts: the practice of Voodoo first developed in the seventeenth century, with its ancestral roots in West Africa. Voodooists worship Bondye, their supreme leader, through interaction with his Loa (spirit) manifestations. These include Damballah (the creator), Papa Legba (gatekeeper to the spirit world) and Ogoun (a warrior). Through offerings and rituals believers appeal to these spirits to temporarily possess their bodies, in the hopes of making a permanent, positive impact on their lives.

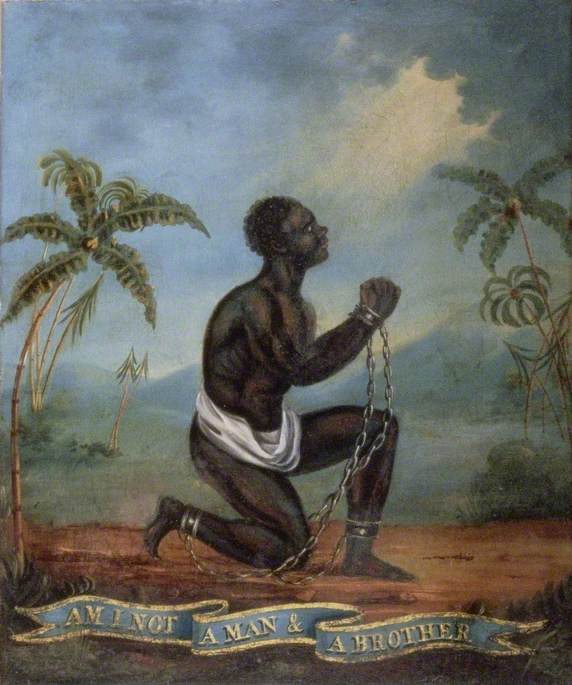

Voodoo is a bona fide religion of Haiti. Yet a closer look at Haitian Voodoo reveals this spiritual practice to transcend religion alone. It could be better recognised as the residual anti-colonialist force that established the first autonomous black nation, via the Haitian Revolution of 1791.

It is also one of the most maligned and misunderstood practices in the world. As the catalyst to the only truly successful slave revolt in recorded history, Voodoo has since become a source of fixation within the white imagination. Cinematic efforts – depicting black magic, or nude black bodies cavorting around raging infernos – have been made to denigrate Voodoo and deracinate the Africans practising it. Popular perception strips Voodoo of its complexities leaving behind a sensationalised gimmick.

Artists like Chris Ofili, Sonia Boyce and Wifredo Lam challenge the colonialist rhetoric upholding these Voodoo tropes, and emulate Voodoo aesthetics in their art. Moreover, in their work, Voodoo becomes a vessel through which to champion African heritage and and dissect colonialist thought.

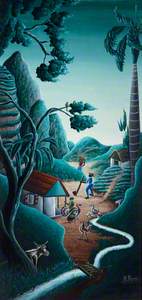

Wifredo Lam

The work of the idiosyncratic artist Wifredo Lam is as full-bodied as its maker's African, Chinese and Spanish heritage. Lam's trademark hybrid figures are a unique synthesis of European Modernist genres, such as Cubism and Surrealism, with African religious symbols and motifs.

Godson to a Santiería priestess, Lam's baptism into Voodoo took place following the firsthand witnessing of a vèvè possession in Haiti. Ibaye translates to 'witchcraft' in Ewe, a language of Benin, which is widely seen as Voodoo's spiritual home. The painting is an abstract melting pot of socio-political and religious references.

From the colonial era, the mantilla, comb and hood of prosperous Spanish matrons is mimicked by the accumulation of forms at the top of the figure's head, while the cascading headdress streams down like a veil on the opposite side. The curved position of the figure suggests a female, uniting the power politics of gender and the power politics of colonisation: the woman's assumed passivity becomes a metaphor for the powerlessness of the colonised.

Cream coloured horns sit atop a shadowy face, in contrast to the smoky grey backdrop. These echo the same horns Papa Legba, the Voodoo spirit guardian to the vèvè crossroads, is often portrayed with. The triangular shapes Lam uses to construct Ibaye stem from the diamond design used in his work since the mid-1940s, to symbolise otherworldly forces, while the painter's perpendicular Cubist angles take inspiration from the angular vèvè artwork used for Voodoo ceremonies.

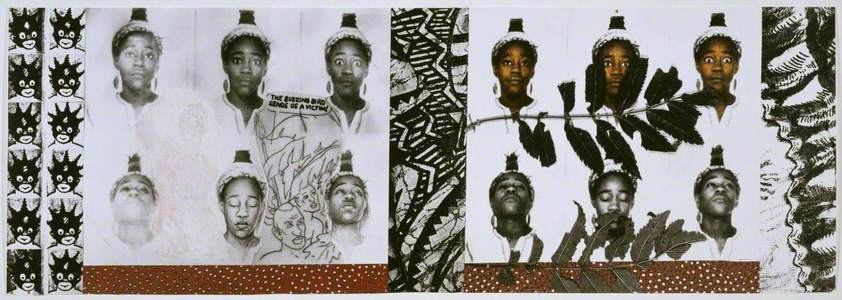

Sonia Boyce

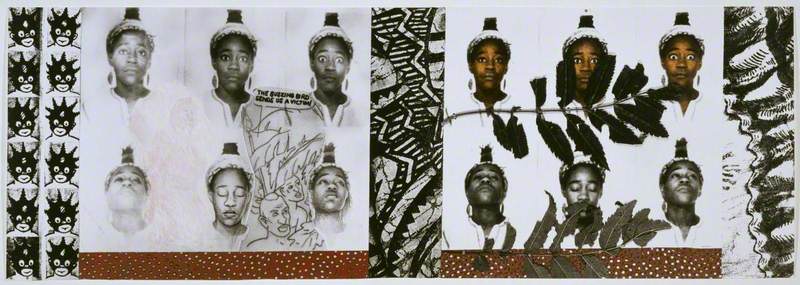

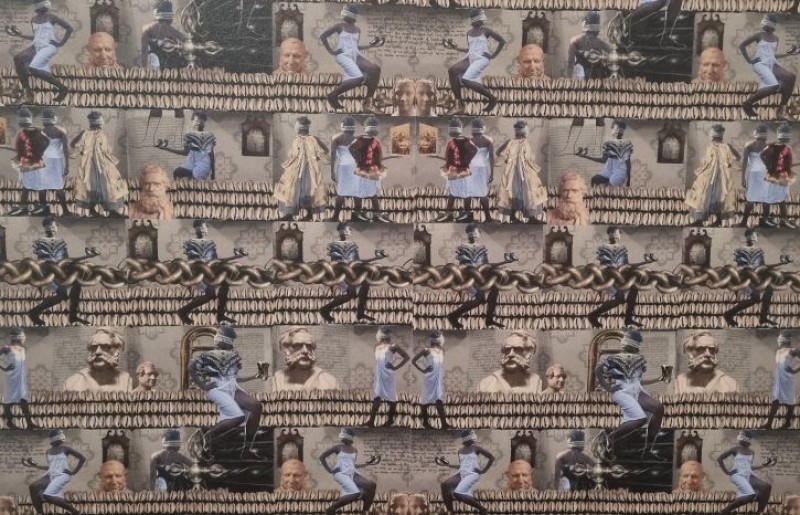

Since the 1980s, Sonia Boyce has been creating art to de-imperialise and enlighten the Western mind. The British Afro-Caribbean artist adopts a Voodooist lens in From Tarzan to Rambo to do exactly this. She uses herself as the subject to investigate the relationship between a classic Hollywood narrative and perceived blackness, disrupting powerful stereotypes of white male supremacy and ironic foolish black naivety in the process.

The sequence of Boyce images are what she terms 'ironic self-portraits'. Part cultural symbolism and part black stereotype, her shocked expressions hark back to the gullible 'wide-eyed Negro' of 1920s and 30s cinema. This is further emphasised by the strip of sinister golliwog picaninny figures, shown on the far left. The six-image series adopts the style of film frames, so we observe this parodying of blackness in cinema, and acknowledge the perversities of colonialist thinking.

However, with eyes shut and head leaning back and forth, Boyce also cites the symbolic gestures of Voodoo trance. Voodoo's 'otherworldly exoticness' is a frequent Hollywood trope for ridicule, and the artist exaggerates this stereotype for black benefit. Trance is a cherished and integral part of Voodoo ritual, reaping a myriad of benefits: here we spy Boyce experiencing it. It appears therapeutic; she is occupying a higher state of consciousness that is incomprehensible to those ignorant of the religion, and is therefore beyond the scope of media mockery.

From Tarzan to Rambo consists of a mixture of materials; photography, collage, fabric and paint. These original sources are interweaved to produce the final artwork. This echoes the syncretism – combining of different beliefs – of Voodoo, which blends archaic sub-Saharan practices of Yoruba, Dahomey and Vodun with aspects of Christianity to produce a Neo-African religion.

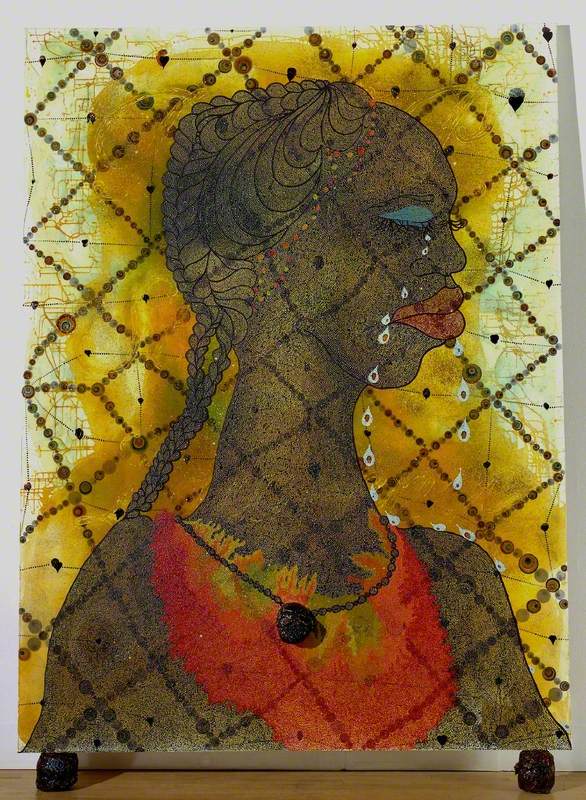

Chris Ofili

British Nigerian artist Chris Ofili's nouveau approach to art places him in a league of his own. His intricate, kaleidoscopic paintings blend resin, glitter, collage – and his trademark elephant dung – to produce multi-layered pieces. Ofili employs a diverse range of cultural and aesthetic sources such as black stardom, Zimbabwean cave paintings and blaxploitation film, to document a complex tale of black history.

Too Doo Voodoo's title means, taken literally, to perform the actions of a Voodoo ritual. This artwork's delicate amorphous centrepiece design loosely resembles Papa Legba's vèvè symbol. Legba is a crucial figure during ceremony whose presence is summoned at the start and end of a ritual in order for it to commence.

Shellacked elephant dung is another focal point in Too Doo Voodoo. For Ofili, dung is a cultural symbol of regeneration, speaking to new growth amid damaged ground. This metaphorically rings true for Haiti, where, following a bloody colonial history, Voodoo emerged as its 'triumphant' spiritual antidote.

Finally, Ofili chronicles black prophets across the scope of black history. The tiny collaged faces of urban and political figures including Nelson Mandela and Snoop Dogg appear bodiless, as if floating through a stream of consciousness. These cut-out magazine faces prove a modern twist to the more religious aesthetic background.

For centuries Voodoo has been the soul of the Haitian people, yet it now faces endangerment. Stigmatisation and miseducation has forced a taboo upon its head. However, artists like Wifredo Lam, Sonia Boyce and Chris Ofili continue to revive its spirit; illuminating both its cultural value and its careful intertwinement with the black experiences of today.

Bex Shorunke, writer