A group of over 400 pictures from Ipswich Borough Council’s collection of works on paper can now be seen on Art UK. It is a fascinating window into a collection that is of huge local importance as well as being nationally significant. The newly added pictures consist mainly of drawings, watercolours and prints from the nineteenth and early twentieth century. These works can easily be damaged by too much exposure to light and their fragile nature means they can be only rarely exhibited.

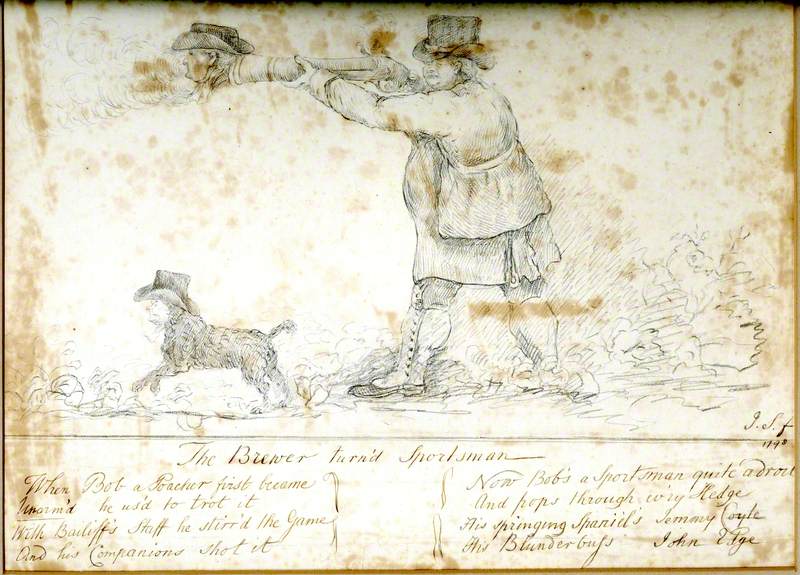

The Brewer Turned Sportsman

1798

John Smart I of Ipswich (1756–c.1813)

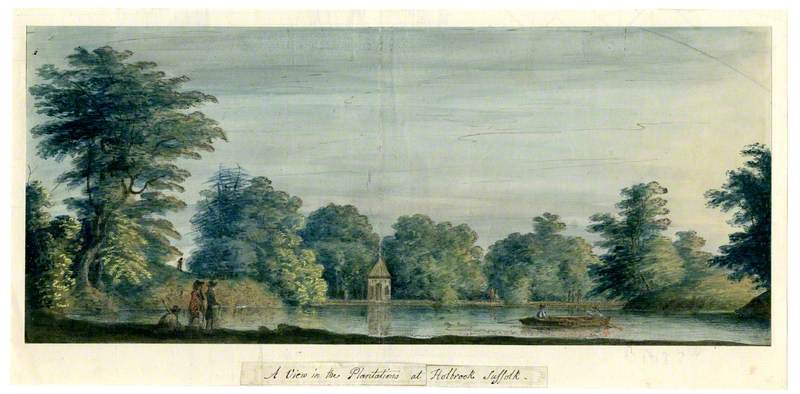

The earliest works featured come from the late 1790s. John Smart’s satirical drawings of local Ipswich bigwigs is an enjoyable place to start. In The Brewer Turned Sportsman from 1798, a rotund local brewer is ridiculed by Smart’s fierce pencil as he blasts a ludicrous human-headed blunderbuss after a poacher with his trusty human spaniel at his side. Mockery and lampooning were John Smart’s trade and pompous local dignitaries were his target. This was a golden age of English satire with the likes of Gillray and Rowlandson at their height, so it is interesting to glimpse a more local practitioner of the art. At a similar time, Luigi Mayer (1755–1803), a Swiss Italian artist, visited Suffolk. Ipswich Museum holds three beautiful watercolours of his visit to Holbrook where he stayed with the Berners family at Woolverstone Hall. This cosmopolitan artist is usually associated with the more exotic landscapes of Egypt and the Ottoman Empire so it is fascinating in pictures such as A View in the Plantations, Holbrook, Suffolk to see his response to the quieter beauty of Suffolk.

A View in the Plantations, Holbrook, Suffolk

c.1800

Luigi Mayer (1755–1803)

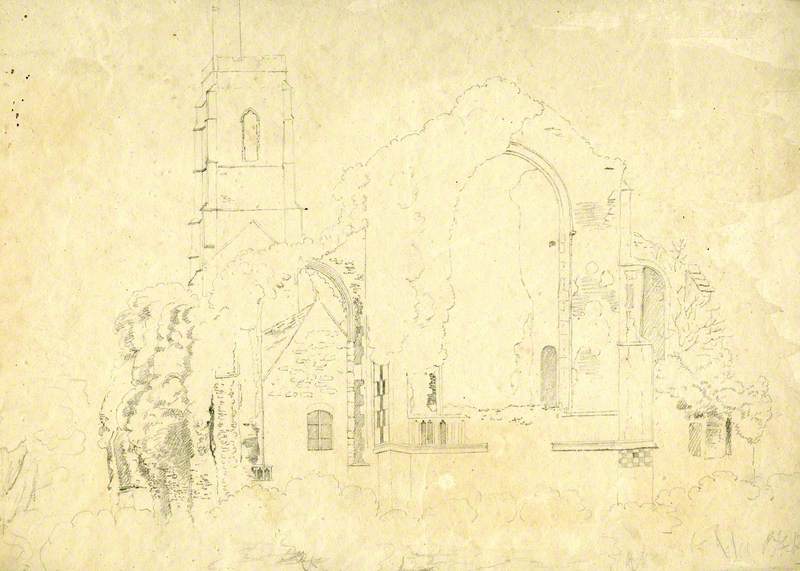

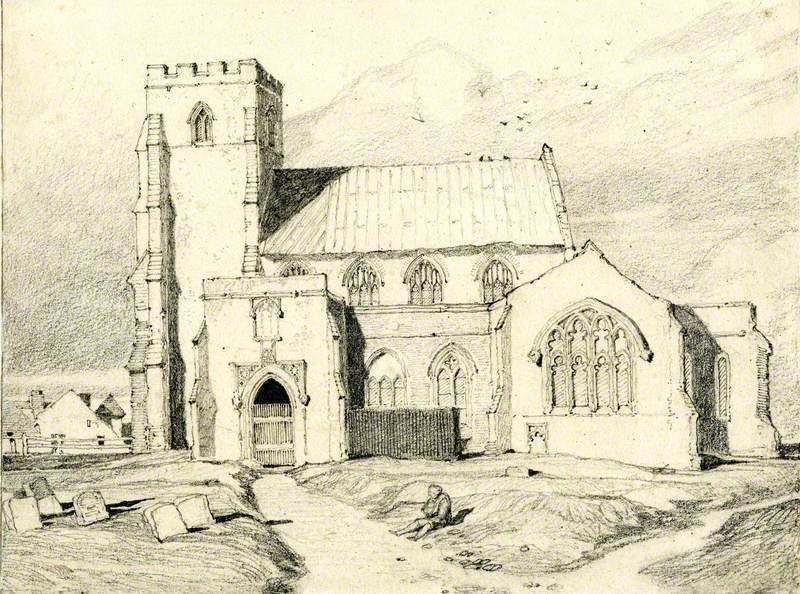

Covehithe Church, Suffolk

1801

Cornelius Varley (1781–1873)

In the early 1800s, there was a great interest in antiquarian pastimes. The aristocracy and the burgeoning middle classes became fascinated with history and architecture. The medieval churches of Suffolk and Norfolk were an obvious focus for their interests and in 1801, Cornelius Varley (1781–1873) arrived in Suffolk on a drawing expedition. The collection contains an exquisite group of his pencil studies from this trip which centred around churches at Bungay. The drawing Covehithe Church possesses a precision and sharp linear beauty which can be seen in all of the drawings, making them an outstanding group whose graphic impact feels almost modern. John Sell Cotman (1782–1842) was working on a similar project in Norfolk. One of the great figures of the English watercolour tradition and a stalwart of The Norwich School, Cotman worked extensively on antiquarian projects in Norfolk and Normandy. Ipswich Museum possesses a stunning group of his church drawings including Great Reedham Church, Norfolk that captures the weight and ancient beauty of these extraordinary buildings and the way in which, over time, they become almost absorbed into the landscape around them.

St Mary's Church, East Rudham, Norfolk

John Sell Cotman (1782–1842)

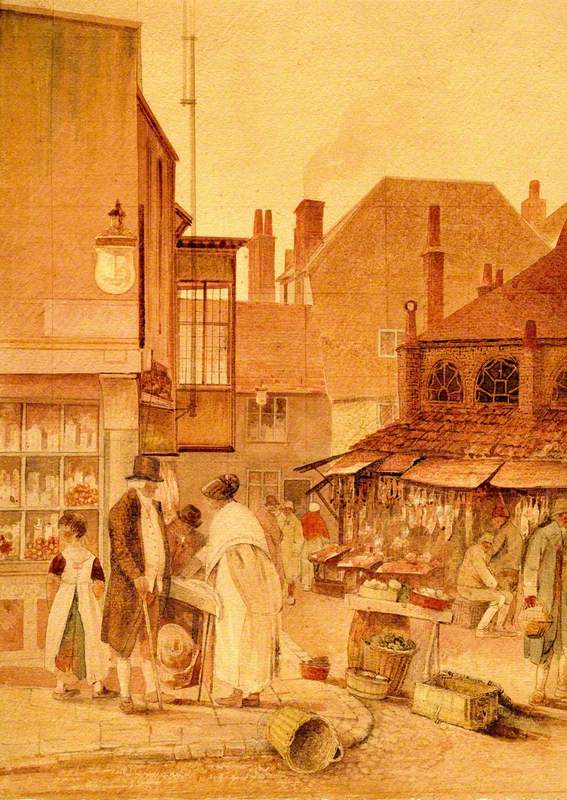

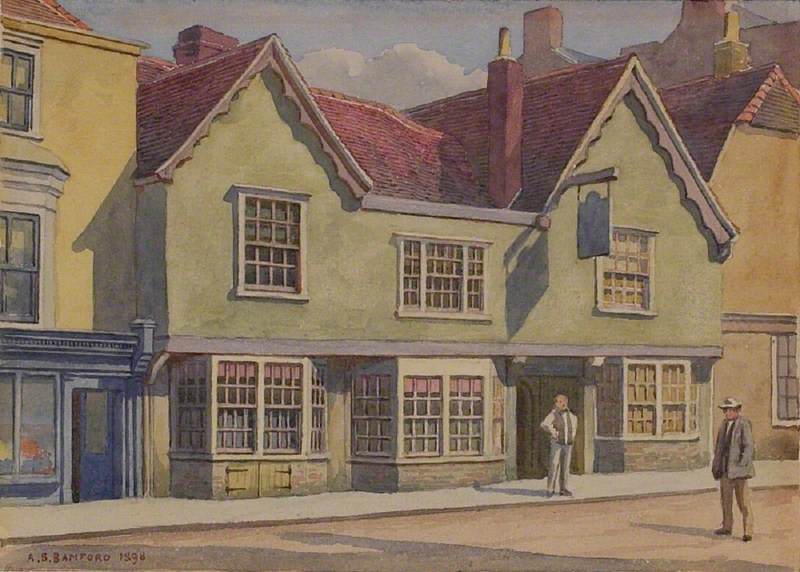

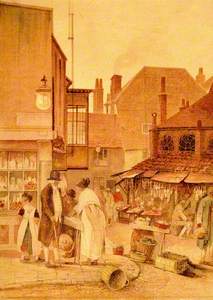

Gainsborough and Constable are considered the two great artists of East Anglia and they are both well represented and documented in Ipswich Museum’s collection. An aim of this project has been to cast a light on the less well-known corners of the collection, so we have not concentrated on these two men. There is, however, an interesting link between the two artists in the form of George Frost (1745–1821). Frost is the great chronicler of Ipswich and its people. He worked for many years with his wife at The Blue Coach Office, which was a thriving hub of business activity in the centre of town. His obsession with the busy streets of Ipswich, its traders and its buildings can be seen in pictures such as Corner of Cornhill, Ipswich. The museum has an important collection of his works and we can gain a very clear idea of how Ipswich, and especially the Cornhill, once looked from Frost’s pictures. All of society is observed and recorded in his drawings and watercolours, from humble street tradesmen, gossips and local characters to wealthy wives shopping in town. He was an avid collector of Gainsborough’s works, owning numerous examples and studiously copying from them so that many of Frost’s landscapes show the influence of Gainsborough in their flowing lines and energetic movement. Frost encouraged John Constable as a boy, taking him out on sketching trips and imbuing a love of Gainsborough and the Suffolk landscape in the young artist. It is interesting to see George Frost as a bridge between these two famous artists.

Woodbridge from Drybridge Hill

Thomas Churchyard (1798–1865)

John Constable, in turn, had a great influence on his friend Thomas Churchyard (1798–1865). Churchyard was a solicitor in Woodbridge but also a prolific self-taught artist. He was a painter devoted to his locality, obsessively painting Woodbridge, the River Deben and its immediate surroundings. His work is deeply imbued with a nineteenth-century English Romanticism and a profound love of the Suffolk landscape. Ipswich Museum possesses one of the most important collections in the world of this quiet artist. A large group of his small, flowing watercolours can now be seen on the Art UK website, bringing these delicate landscapes to a much wider audience.

Landscape is a theme which runs throughout the art of Suffolk. Philip Wilson Steer (1860–1942) brought Impressionism to East Anglia in the later part of the century, capturing the delicate long light which is such a feature of the area. A group of his pale fluid watercolours, including Harwich, have been added the Art UK website, alongside his better-known oil paintings. In Steer’s work, the emphasis moves towards the coastline. His work will always be associated with Southwold and Walberswick and he captures exquisitely the atmospheric flatness and the luminosity of sea and sky of this eastern edge.

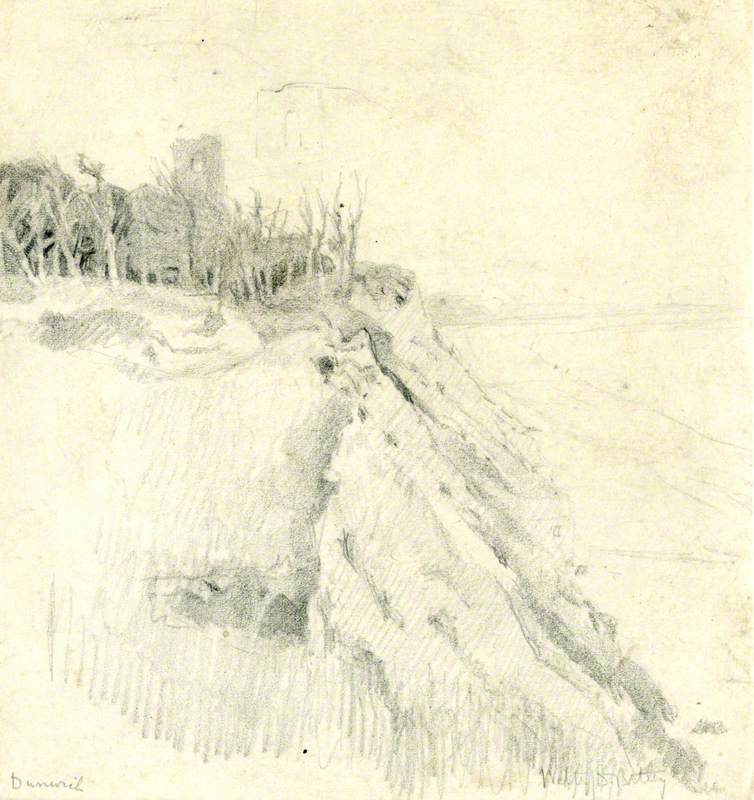

Further along the coast, Walter Batley (1850–1936) found inspiration in the crumbling cliffs at Dunwich in the early years of the twentieth century. His drawings from 1913 capture the ruined tower of the church as it teeters on the edge of oblivion. He captures a moment in Dunwich that is now gone, when there was still a church to be seen. Batley absorbed the influence of Wilson Steer and English Impressionism, creating a deeply atmospheric vision of this corner of Suffolk. His exquisite drawings and watercolours of trees and shore possess a profoundly elegiac atmosphere in the years running up to the First World War. A similar sensibility might be seen in Harry Becker’s (1865–1928) paintings of agricultural workers engrossed in hard silent labour. In Reclining Man in a Cap, we see a farmworker depicted in bold oil-painted strokes, a young man from a remote country village who was probably sent to war in 1914.

A Reclining Man in a Cap ('Forgotten then were the disconsolate, the rainy days')

c.1913–c.1928

Harry Becker (1865–1928)

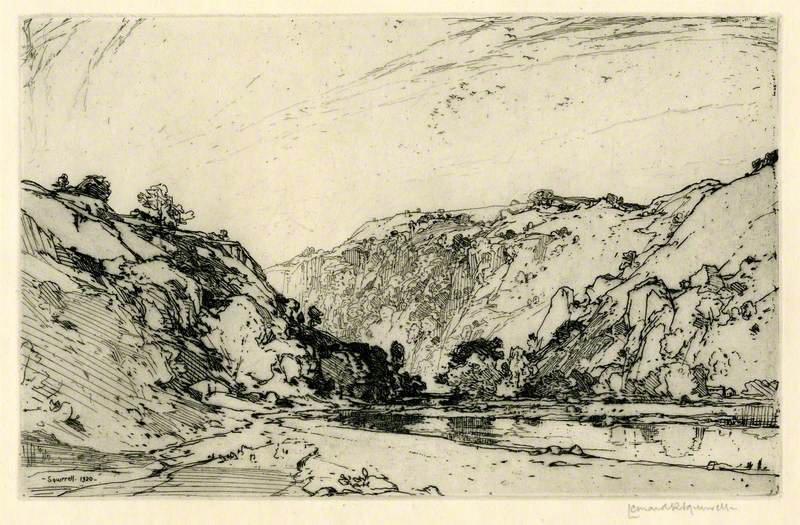

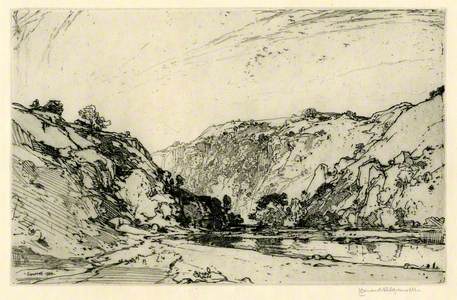

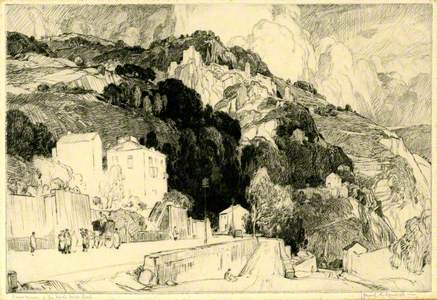

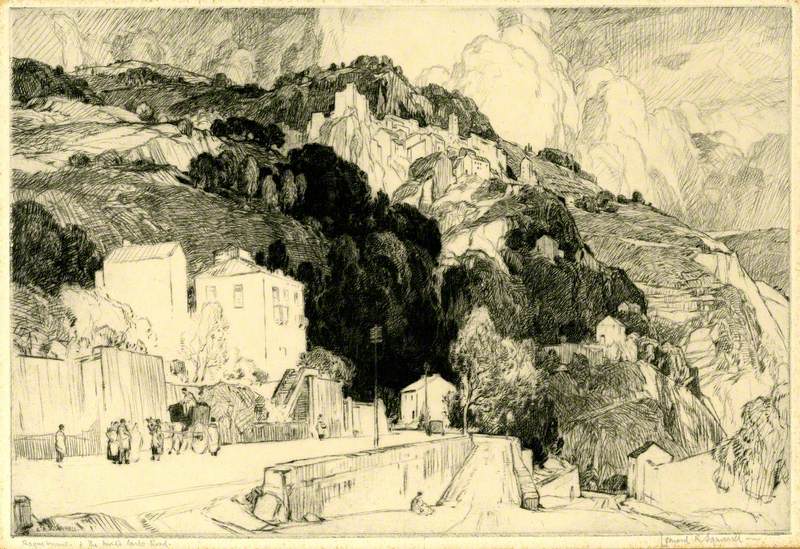

Leonard Squirrell (1893–1979) has become a popular local artist in East Anglia. His drawings and paintings possess a breathtaking clarity and detail which allows the viewer to absorb themselves in his depictions of local places. He is mostly known for his views of Suffolk towns and villages drawn with controlled precision, but a collection of his early etchings at Ipswich Museum depict much hillier climes in France and Derbyshire. It is interesting to see In Dovedale, Derbyshire, an etching from 1920, and how the grandeur of the landscape brings out a more dynamic line from the young artist. There is the same graphic energy in the dramatic Roquebrune Castle and Monte Carlo Road from the same decade. Both etchings interestingly illustrate the way in which that youthful, almost passionate, draughtsmanship from the 1920s eventually settled into the cool clear observation of the mature artist.

Roquebrune Castle and Monte Carlo Road

Leonard Squirrell (1893–1979)

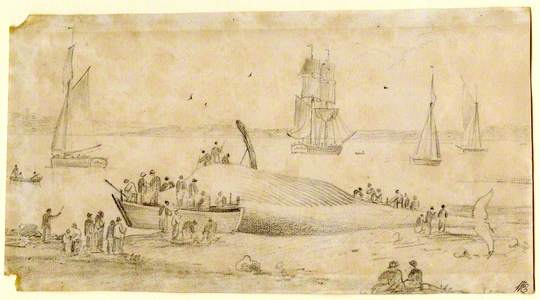

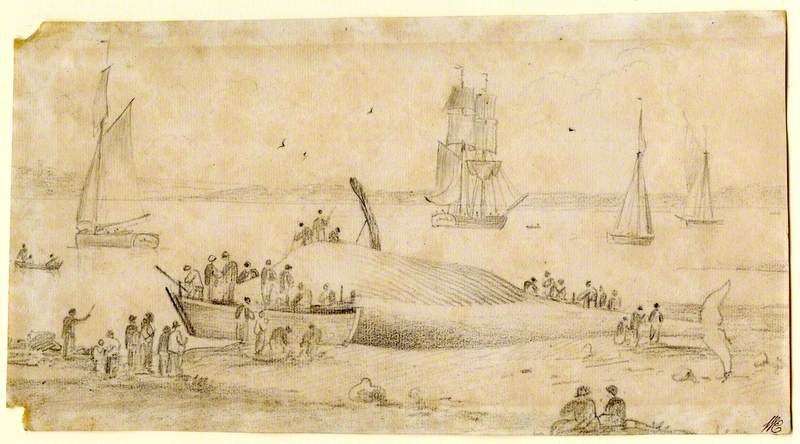

The Whale at Downham Reach, Ipswich

c.1816

George Frost (1745–1821)

There are many other artists represented in the Ipswich Museum collection: some are well-known, such as David Cox and John Crome, some are lesser-known figures such as Samuel Read, Edwin Edwards and Cecil Lay. There are intriguing pictures, such as Henry Davy’s eyewitness account of Daniel O’Connell’s speech in support of the Irish Cause on the Cornhill in 1836, or George Frost’s drawing from 1811 of a beached whale pulling crowds at Denham. This new resource will provide lots to ponder, research and enjoy.

Michael Sheehy, illustrator, musician & Training Museum trainee