Some of my fondest and earliest memories are of drawing. The very earliest of these was drawing a teddy bear’s hard nose across a distemper-painted wall, when I was around four or five years old, and being profoundly affected by the sensation it gave me and the rich line it left behind. This incredible sensation stayed with me all through my childhood and it is still important today.

It was the one and only time when I almost felt like an explorer, in the Victorian sense. It was a majestically peaceful and sublime place to be.

This feeling fuelled my love of all things to do with art but it was drawing that I had a special love for. It seemed natural to me to want to continue drawing and painting and take this onto an art school. This wasn't to be, partly because of the perception the institutions had in the late 1960s – fuelled by stories in the popular press of revolution, sex, drugs and rock and roll – and partly because art was the only subject I excelled in, having pretty much failed at everything else. So, with my parents not wishing their son to become a beatnik or a dropout sitting around and not paying his way, it was ruled out for me.

By the summer of 1973 I had left England. Embarking – ironically – on the hippie trail overland to Kashmir, although I tried to distance myself from thinking I was just one more of many.

I drew all along this route, mainly self portraits, and I also took the odd photo of unlikely things with the cheap camera I had with me to record my adventure. I have some great, although fading, memories of Afghanistan that embodied and brought to life all my fantasies of what the East must look like. Leaving the country via the Khyber Pass was equally impressive, almost as if I were travelling through one of Turner's dynamic watercolours of an Alpine pass. Sadly I made no sketches of any of it and the one drawing I did make, in the garden of the hotel in Kabul, was looking down on my foot.

Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps

exhibited 1812

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

I had virtually run out of money before reaching Afghanistan and had asked my parents to wire me £120. They duly obliged and included a letter along the lines of 'We both work extremely hard for our money...' and not to ask for any more.

I decided to carry on down the Khyber and arrived in Peshawar, which really felt like the beginning of something bigger and more exciting.

Pakistan was not a favourite on the overlander's list of countries. The generally held view was to get through it as fast as you could and get spaced out in Goa. After a lengthy stay, holed up in the grimy and dilapidated National Hotel in Peshawar, I was lucky to tag along with some people going up to the Hunza Valley. A fabled place, which had been out of bounds to foreigners since partition – until then. It was exhilarating to experience a place that had been isolated from foreign visitors and present day tourism. It was the one and only time when I almost felt like an explorer, in the Victorian sense. It was a majestically peaceful and sublime place to be.

To go on to Indian-administered Kashmir, my original destination, meant going back down to the Punjab and crossing the Wagha border between Lahore and Amritsar, then up to Jammu and Kashmir. My first memory of the City of Srinagar was of the large modern tourist office and on seeing it I could not help but feel deeply deflated. I should have expected this, it being a well trodden destination from the colonial days.

Dhaba near the Golden Temple, Amritsar

Martin Yeoman, pen and wash

I lodged in a servant’s boat on Dal Lake, a larger version of the Shikara. Slender boats were moored alongside the old houseboats, much as I remembered seeing along the River Thames at Staines as a boy.

One evening in my tiny rear cabin I sketched a figurine that was there. Each time I drew it I made it look slightly different. As it did not move I came to the conclusion that I simply wasn't looking nearly as carefully as I should. It was an important moment of change for me.

Next morning I asked the old turbaned houseboat owner – who had a great face – if I could draw him, with the intention of really getting it right. I also made sketches of him as he went about washing up and preparing various meals. During a time back in London when I made my living as a commercial artist I always hated method, particularly technique, and to a degree style too. Finding your own style was something people often talked about and it seemed to me that the more distinctive style you could develop, the more people would be attracted to what you did.

South Yemeni tribesman

Martin Yeoman, pen and oak gall ink

I stayed for some time on Dal Lake and during my time there managed to catch the top of my foot on something, and the wound would not heal. I left the valley and headed down to Amritsar, but by the time I reached there, my foot had swollen to such a degree it was difficult to get it in and out of my boot. Fellow travellers at the Golden Temple where I stayed thought it was looking gangrenous and advised me to seek medical advice from the hospital across the border in Lahore. Whatever it was that I was lucky to receive from there, it cured my foot, my cold and also my diarrhoea. After crossing the border back and forth between India and Pakistan half a dozen times, I finally settled in Lahore at the point of being desperately short of money. I sold the presents I had bought along the way; most significantly I sold my simple camera. The rupees I got in exchange for it were out of date and worthless.

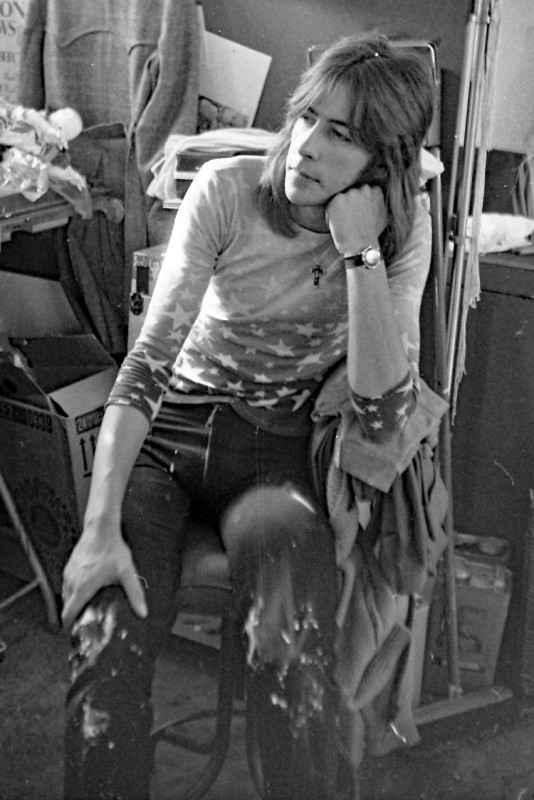

Alan Springal

Martin Yeoman, 2014, crayon

Very soon the dreadful moment came when I had nothing left at all to live on. I remember very well the feeling of trying to hold onto the last few pennies and the anxiety and depression of the moment of finally becoming penniless. My luck happened along in the form of a young curate who offered me some temporary shelter in the vicarage. Now, whether it was from him or from me, the decision was taken to draw portraits on the street for money. The streets of Lahore would not have been a great place to set yourself up as a portrait artist, so I retreated to the relative peace of the front lawn of the University of Lahore. I was reminded of the people who drew portraits in Leicester Square and outside the National Portrait Gallery back in London, but I wanted to do something different than I remembered them doing. So I set about making real drawings of all comers for about three or four rupees each, and let the drawings come out of intense observation rather than imposing an artistically acceptable style on them. Not all of them were successes and it worked out that about every tenth drawing was a good one, causing the occasional argument and the odd ripped drawing should some former sitter hang around and see something better come along.

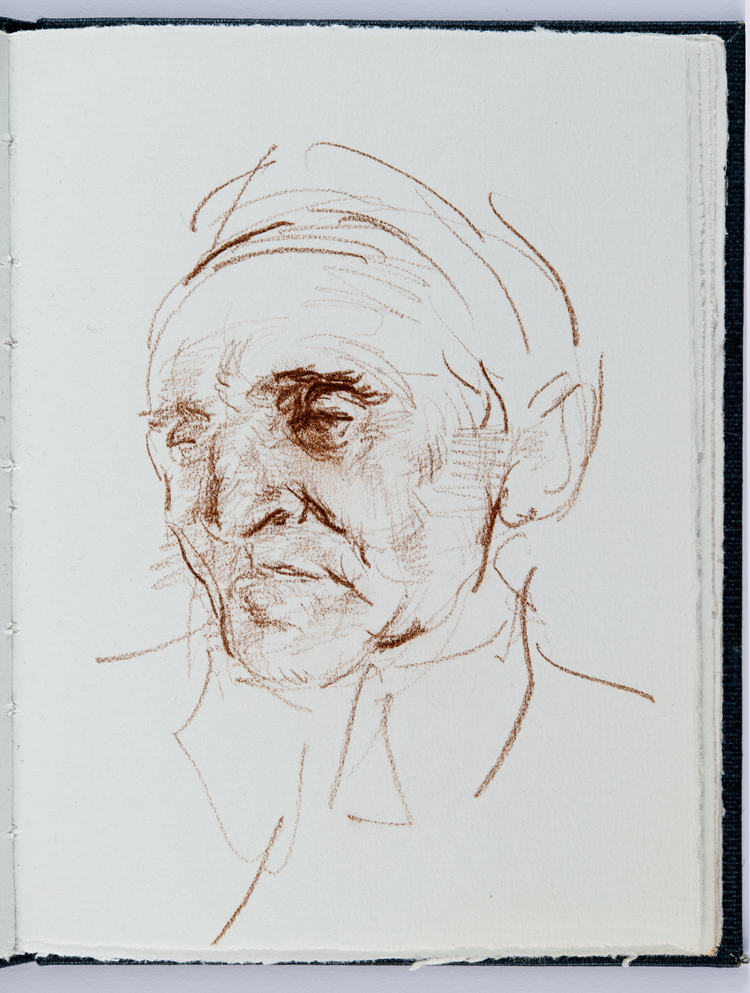

George Yeoman, age 18

Martin Yeoman, 2016, crayon

I was obliged to leave Pakistan due to an important gathering of Heads of State from the Arab world for a conference on Muslim unity in the country. I took a train down to Quetta and eventually arrived at a place that I remember felt like some old frontier town of the American West. Imagine my astonishment then to be met at 7am outside the station by a rickshaw driver who asked 'did I draw?'. I was taken to an area of low buildings and shops. Inside the shop, the walls were covered with drawings, presumably made by westerners like me who had passed through. Some were quite good, but most were commonplace, and all were drawn in pencil, biro or both.

The owner was not there so I sat and waited for his arrival. This gave me the time to realise that I had an edge here with the oil pastels I carried with me. So when the owner turned up I made a drawing of him in those. The shop owner liked it so much he persuaded every customer to sit for a drawing by me, whether they wanted one or not. By the close of the day I made enough money to eat and drink and get a room for the night, and to buy the all-important bus ticket to the border of Iran. It was only then that I realised the shop's merchandise was hashish, after I was asked if I would like to buy a couple of kilos to take home with me by two of the customers. Not a great idea for one who was intending to cross the border into Iran where the death penalty awaited those trafficking drugs of any sort... perhaps they were two unhappy customers of mine.

I drew my way in exchange for lifts across Iran to the city of Tehran. Once there, the dramatic fall in temperature, in a modern city with a modern city way of life, made making a humble living drawing portraits dressed in worn out old clothes feel impossible. So with great regret I succumbed to getting myself repatriated by the British Government. I was given a dressing down by the second secretary at the British Embassy. He was explosive in his rebuke and blamed me and my kind for letting down the entire United Kingdom. I was given a train ticket and the barest subsistence to tide me over until I reached the Embassy in Istanbul, and to take me from there to Victoria.

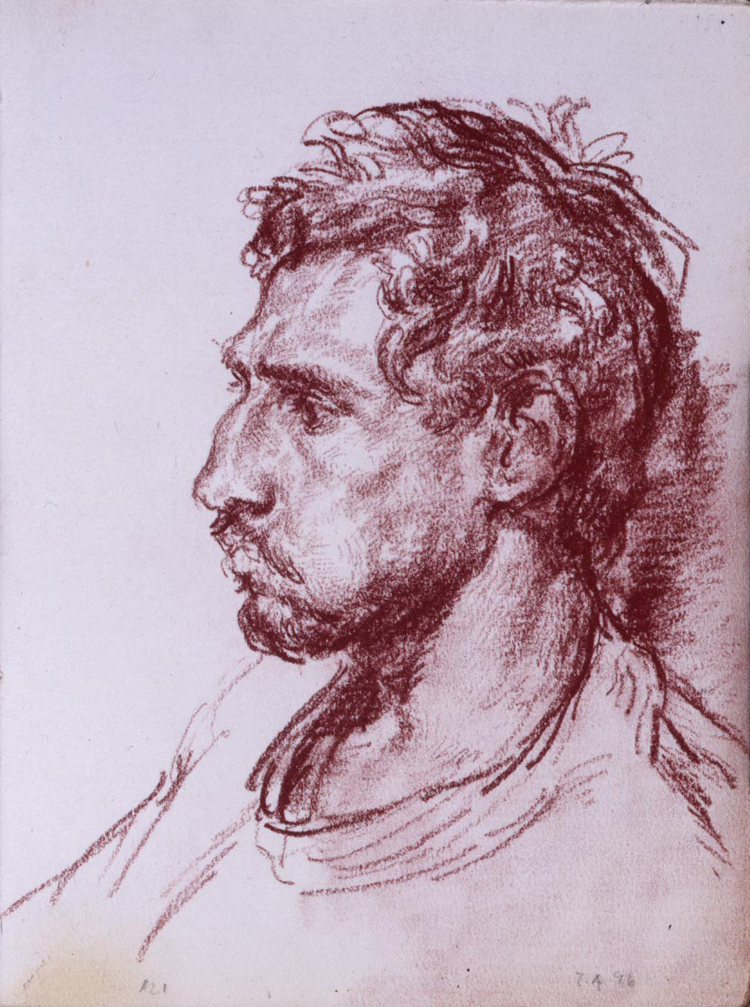

Model sitting back

Martin Yeoman, 2016, crayon

Returning to England, I decided to find an art school I could attend.

After many lukewarm interviews my mother suggested I go and see the Royal Academy, which had a school. I went without any expectations other than to show them what I had achieved and to hear their opinion, which by now had become important. I had also told myself prior to the meeting that whatever the outcome, I would still pursue the path I saw for myself, as I was now very determined to be an artist.

My first interview was with the school's Curator, Walter Woodington, who asked if he could hold on to my drawings to show his colleague. I returned for a second interview with the Keeper of the Schools, Peter Greenham. Towards the end of the interview I felt I should confess to them that I had once been a commercial artist, feeling that I had rid my drawings of any trace of it but it had already been clearly detected. Nevertheless I was given the benefit of the doubt and was asked if I would like to attend Jane Dowling's life drawing classes held at Oxford Polytechnic once a week. Every now and then I went up to the Royal Academy Schools to show Mr Greenham my progress. Later the Keeper asked me if I would like to come to draw at the Schools a couple of days a week. This progressed on to painting and finally a portfolio of my studies was put together so that I could apply as a full-time student.

Ali chewing qat, Sana'a sauguine

Martin Yeoman

Being taught drawing and painting, first by Dowling and then by Greenham, had a profound effect on me. Neither of them tried to bend me exclusively to their way of seeing and neither did they try to take me back to the very beginning and away from any ‘preconceived notions' I may have had about drawing and rebuild me afresh: a practice that was common at art schools in the 1960s and early 1970s. Instead they helped me to improve vastly on what I had already learnt by myself.

I was impressed too by the way Greenham taught drawing in the life drawing room, which was by demonstration rather than with words and diagrams. His demonstration drawings always had great clarity and understanding of form. It was about form and working from the inside of the form outwards where I learnt the most from him.

So either by chance or destiny, this was the one great opportunity in my life that I had been seeking and I grasped it with both hands. It was also the fulfilment of a wish, made several years before, one afternoon in 1972.

I was completely earnest and disciplined in all my studies there and so profoundly instructive were the lessons that I received during my time at the Schools, that over 40 years later I am still able to take from them.

The title of this piece refers to a quote by Delacroix, 'A note at the time is worth a thousand recollections'.

Martin Yeoman, artist

Find out more about Martin's work on Twitter, Instagram or his website.