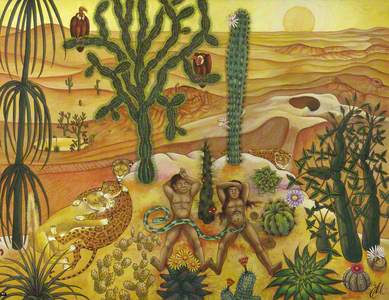

On 21st November 1931, a young man called Arthur Jeffress threw an extravagant Red and White party: clothes, food, and drink were limited to those two striking colours.

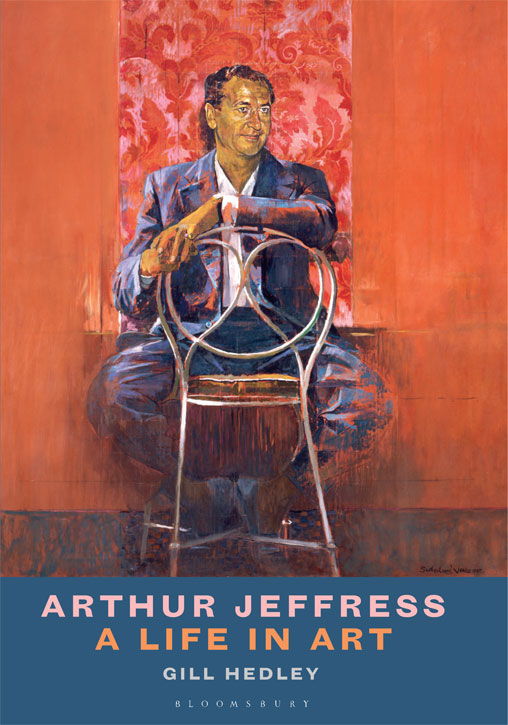

Cover of 'Arthur Jeffress: A Life in Art' by Gill Hedley

As host, he wore an outfit of white 'angel skin' with such wide trousers that it looked like a skirt; another guest wore only a (largish) red-and-white spotted hankie. A pianist, who often played at the Blue Angel nightclub, played Body and Soul dressed as Elizabeth I with a bright red wig.

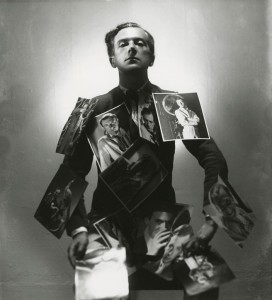

Arthur Jeffress at his Red and White Party

1933, photograph by unknown artist, from an unknown newspaper

The timing was awful as there were hunger marchers on the road and the event has been described as the end of the 'Bright Young Things' subculture in Britain.

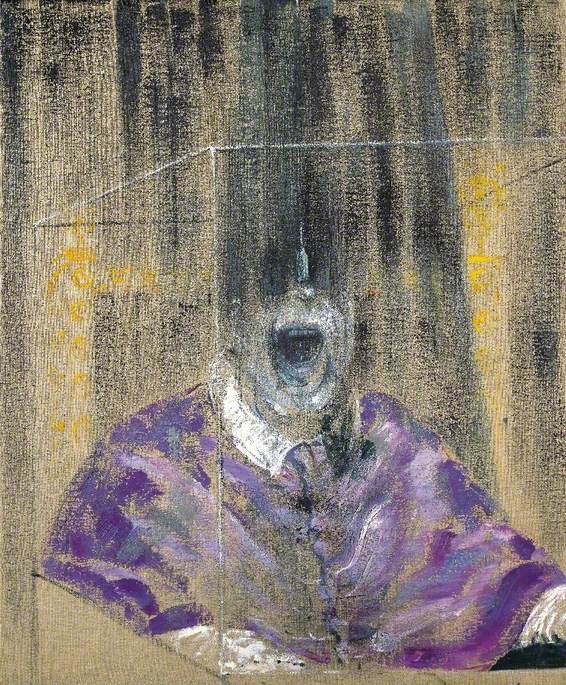

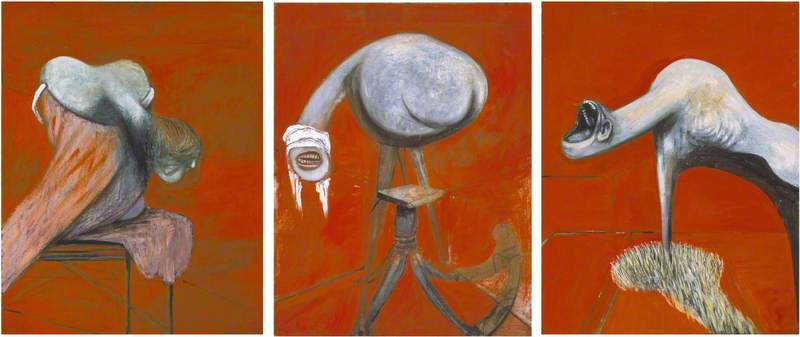

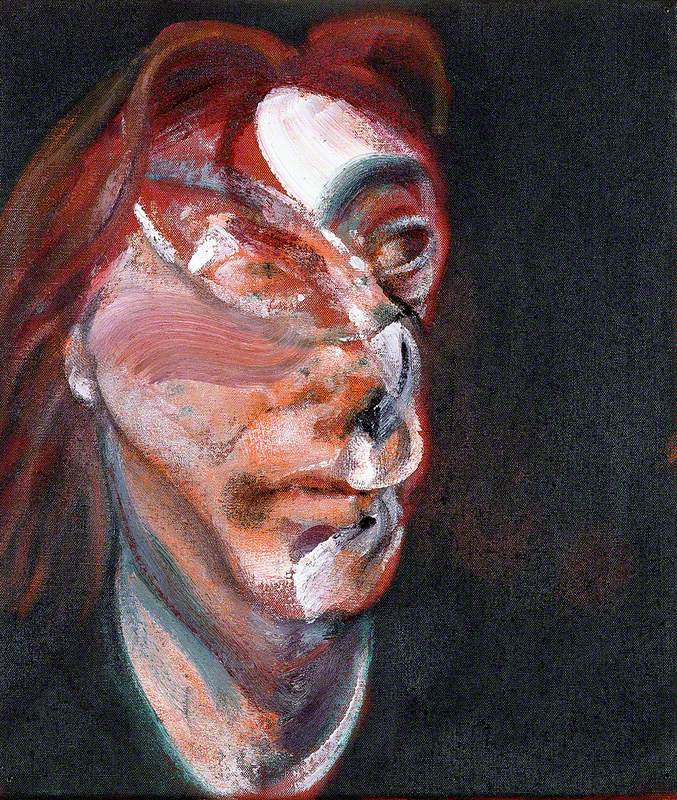

Arthur Jeffress turned 26 that night. He had inherited the equivalent today of £10 million before he was 21 on the premature death of his father and had great fun spending it. He left Cambridge University, become an experimental actor very briefly, travelled widely and began to buy art. In the early 1930s, he had begun to live with the aspiring artist John Deakin who later worked closely with Francis Bacon, most notably on a series of photographs of Isabel Rawsthorne.

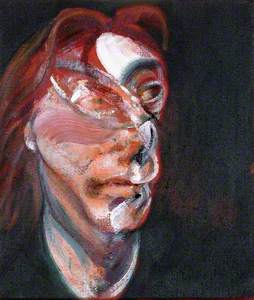

Three Studies for a Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne

(panel 3 of 3) 1965

Francis Bacon (1909–1992)

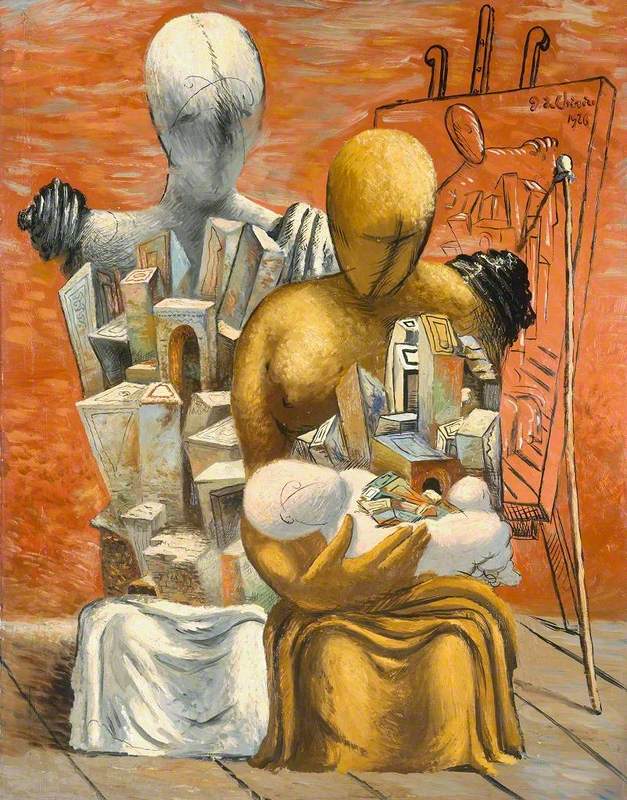

Jeffress and Deakin split up in 1939 and both went on to have fascinating careers during the Second World War. Deakin worked as an army photographer and his innovative wartime images are not yet well enough known: many of them are in the Imperial War Museum archives. Together, Jeffress and Deakin had bought more and more work for Jeffress's collection including The Painter's Family by Giorgio de Chirico.

in 1945, Jeffress returned to the country house that he had bought for himself and Deakin at Marwell near Winchester, now filled with art and glamorously decorated. He renewed contact with the young curator, Loraine Conran, at nearby Southampton Art Gallery which opened in 1939 but tragically was bombed in November 1940.

After the war, Conran needed to move fast to recreate the gallery and wisely approached local collectors for their support. In 1946, Jeffress replied warmly to him that it was 'nice to hear from him after all this time'. In a speedy exercise of liaison, with skills learned in the war, within a month Jeffress lent a sizeable number of his paintings to the gallery for an exhibition in the summer of 1946 which over 14,000 people visited. The list of artists included Picasso, de Chirico, Soutine, Rouault, Derain, Modigliani, Balthus, Dufy, Vuillard and Vlaminck. He mentions that he wants to sell his Giorgio de Chirico:

'You remember it in the hall – huge rhomboid faceless heads & bodies filled with rectangular shapes? It is very cheap – £200 – would the gallery be dashing enough to buy it?'

They were not so dashing; it was sold to Princess Marie Callimachi and then purchased by the Tate in 1961, at the same time as the Jeffress Bequest was being allocated to them. A Southampton Art Gallery attendant asked Arthur to explain the work to him and he countered that he was never able to explain modern paintings and whenever he felt the need of an explainable painting he bought a nice coloured postcard. He was sure that the man thought he was mad.

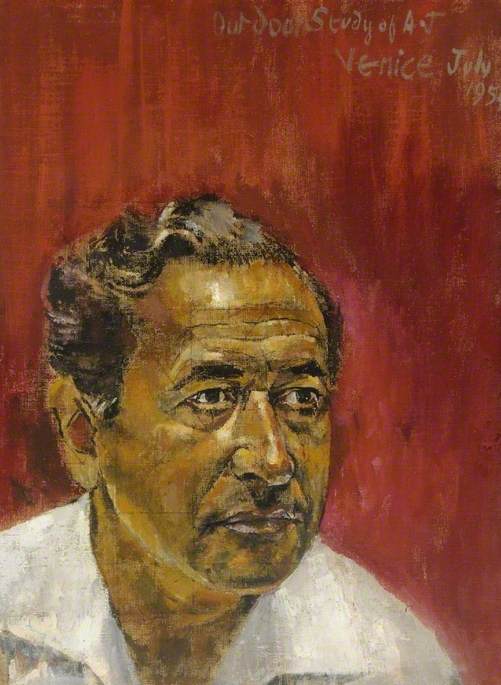

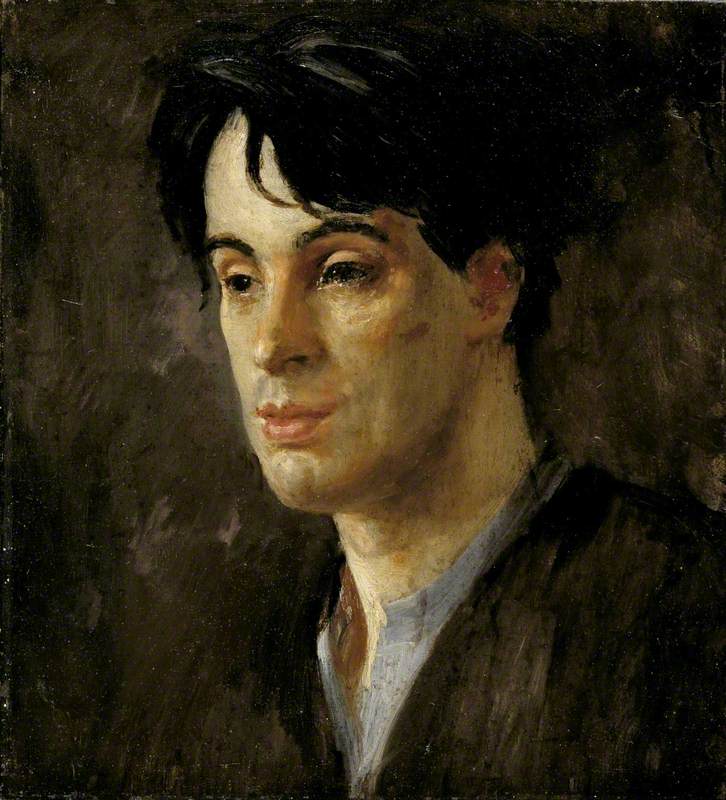

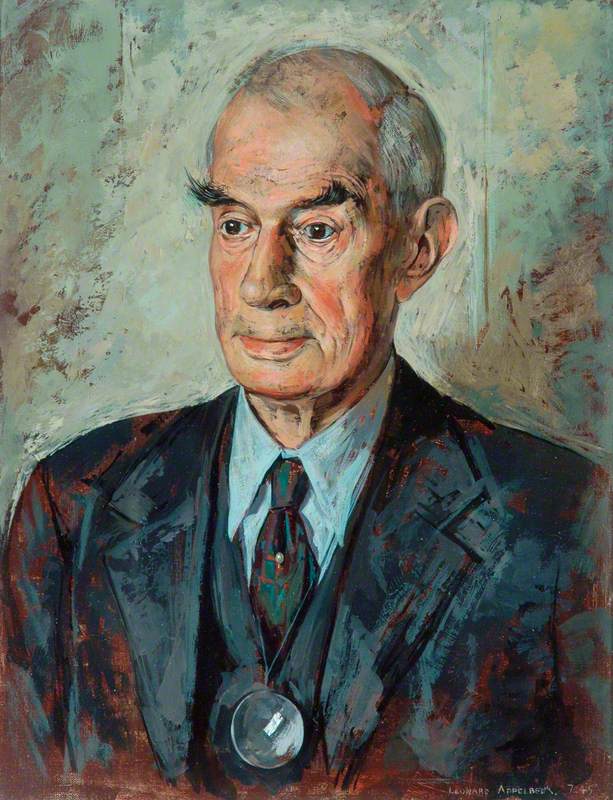

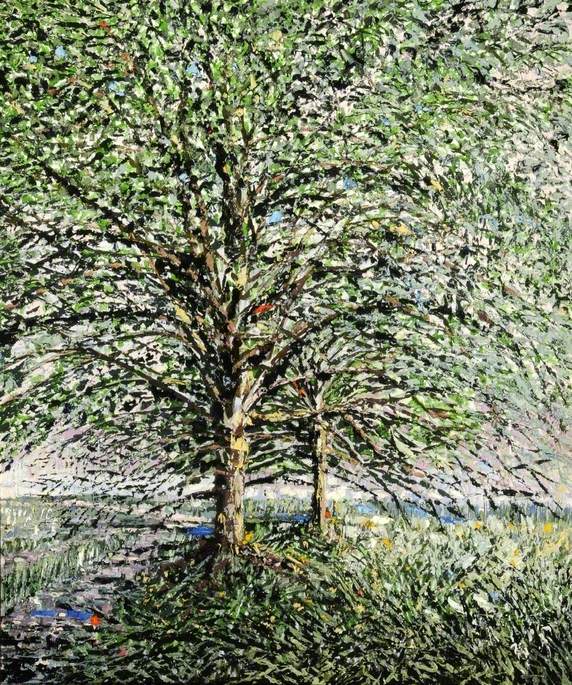

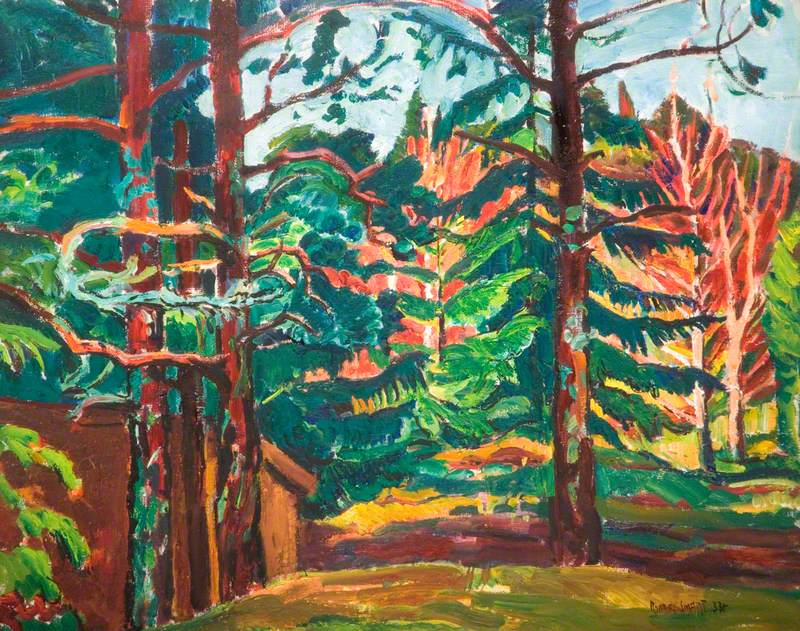

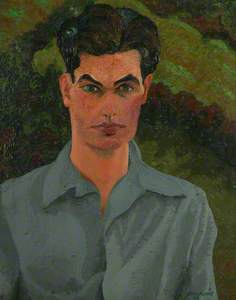

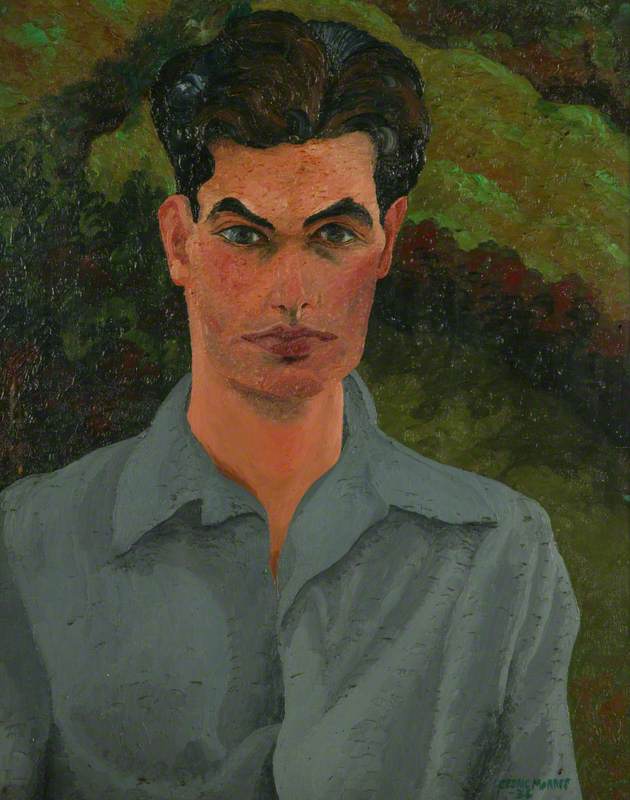

(George) Loraine Conran (1912–1986)

1930–1934

Cedric Lockwood Morris (1889–1982)

Loraine Conran was a well-connected and intelligent man who got on well with Jeffress. But which of them was behind an astonishing new local venture? In 1947, then again 1948, an organisation called The Circle for the Study of Art (CSA) held exhibitions in the very conservative setting of The Judges' Lodgings in the Close of Winchester Cathedral. Local Hampshire collectors, like Stanley Spencer's patrons the Behrends from Burghclere, lent modern works, none very avant-garde. But there was one very notable exception.

In the second exhibition of CSA, a work by Jackson Pollock was shown in Britain for the first time. Jeffress lent it and a less likely setting for such a work of abstraction cannot be imagined. Exactly which work he owned is not known. Nor do we know how involved Jeffress and Conran were in the organisation of CSA: Jeffress lent to both shows and Conran opened the first one. The work by Pollock (Jeffress might even have owned two) will have been bought in New York in 1945. Jeffress always said he loathed all forms of abstraction but his life was a contradiction in so many ways.

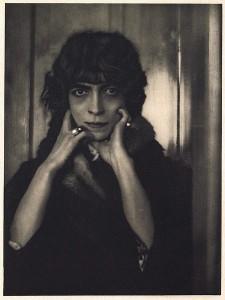

Jeffress gave up his Hampshire house and moved back to London, with no idea how to occupy his time. He met Erica Brausen at a party and this unlikely pair decided to work together. She opened the Hanover Gallery with Jeffress as her main backer and playing a very active part in the gallery. So too did Erica's lover, the fabulous (in all meanings of the word) Toto Koopman.

Brausen's spur to opening her gallery was her sale of a major painting by Francis Bacon to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Bacon and the Hanover made each other's reputations, but Jeffress and Bacon did not get on at all.

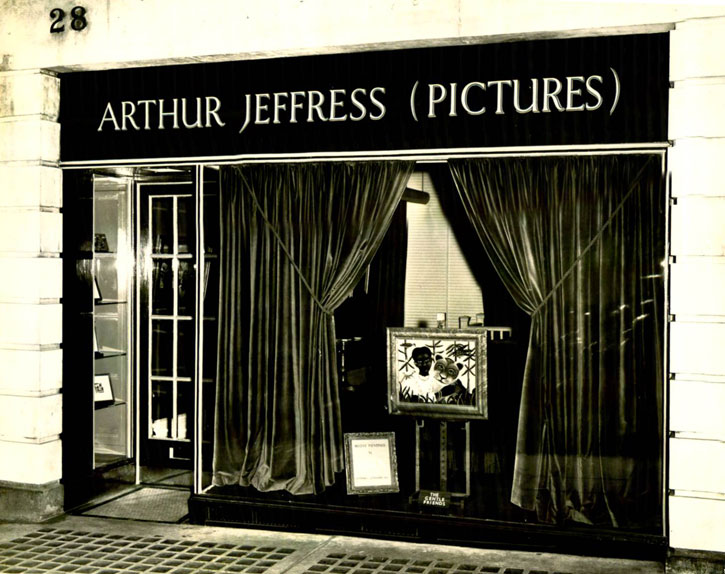

The Arthur Jeffress Gallery

photograph by unknown artist

In 1955, Jeffress set up his own gallery in Davies Street, Mayfair, and had a sell-out opening show with the work of his favourite artist and beloved friend E. Box, whose work could not resemble Bacon's less.

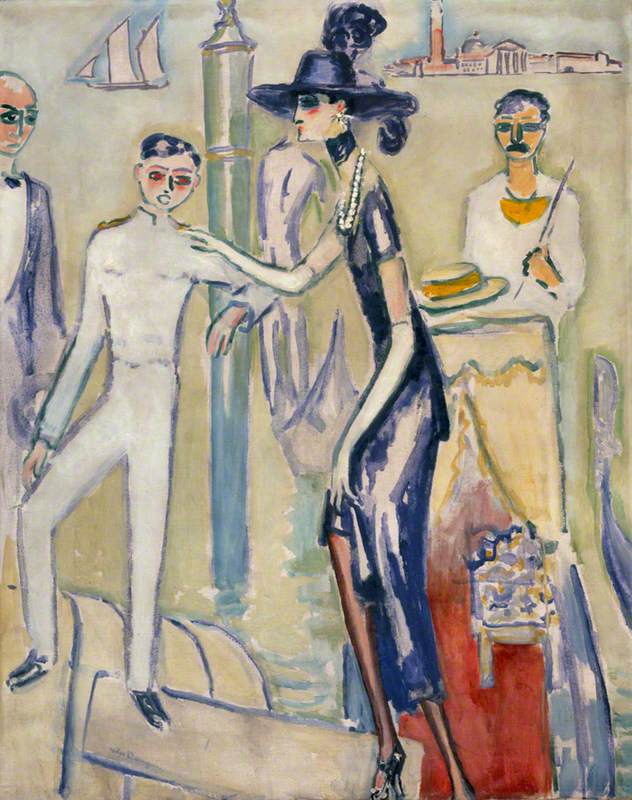

From then on, Arthur Jeffress divided his time between exquisitely decorated homes in London and a small but lovely house in Venice where he had his own gondola and two gondoliers. He lived a luxurious life but a risky one as his flamboyant homosexuality was never hidden. Letters from Jeffress to his gallery manager, the art critic Robert Melville, paint a wonderful picture of the period and are the basis, along with much other research, of a new biography, Arthur Jeffress: A Life in Art.

The cover reproduces the portrait by Jeffress's dear friend Graham Sutherland which was bequeathed to Southampton, along with 98 other paintings, on Jeffress's suicide in 1961.

This sad part of an otherwise entertaining story is revealed in the book for the first time.

Tate was also a beneficiary of his will and all paintings bequeathed or given by Jeffress are on the Art UK website, many showing his beloved Venice.

A study for the Sutherland portrait, painted in his Venice garden, is in Doncaster.

Many other works belong to what was described in a review as 'a subversive little collection' but there were also real highlights including a portrait by Toulouse-Lautrec, a late Monet and a Picasso of Dora Maar.

Sadly, an exhibition to mark the publication of the book has now been postponed because of the coronavirus but is planned to take place later in 2020 in Southampton City Art Gallery. Meanwhile, here are some images that could not be included in the exhibition – yet another of the wonders and possibilities of the Art UK website.

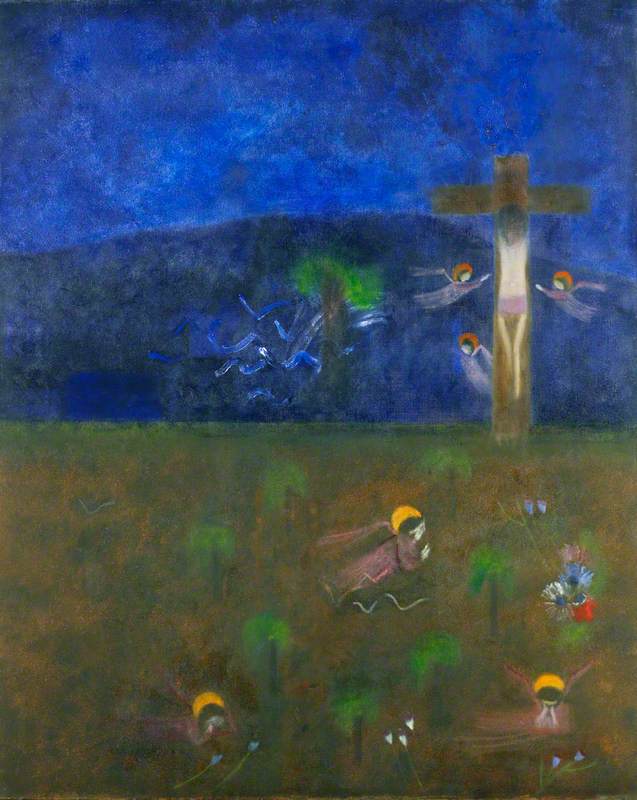

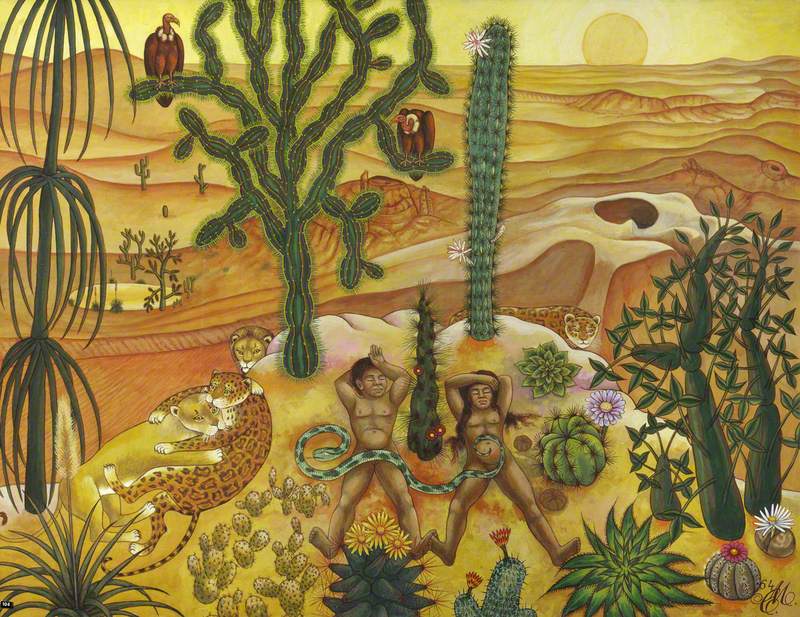

Desert Idyll (Homage to Arthur Jeffress)

1964

Coqué Martínez (1926–c.2011)

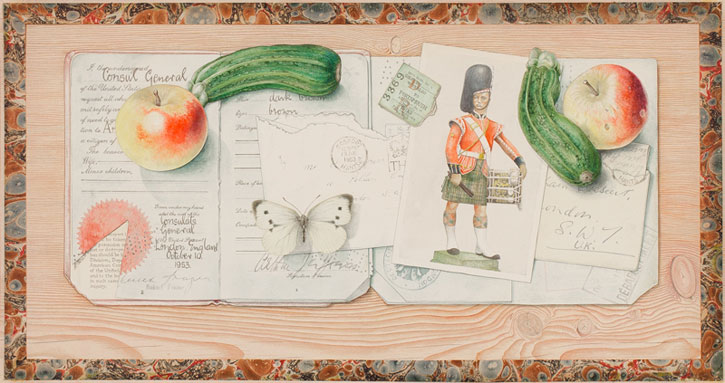

A Trompe l’Oeil for Arthur Jeffress

illustration by Richard Chopping (1917–2008)

Jeffress had two particular favourites among his paintings. One, a portrait by Baron Gérard of Napoleon was installed theatrically in all his English homes.

The portrait of Napoleon on display at Marwell Lodge

photograph by unknown artist, from Jeffress's photo album

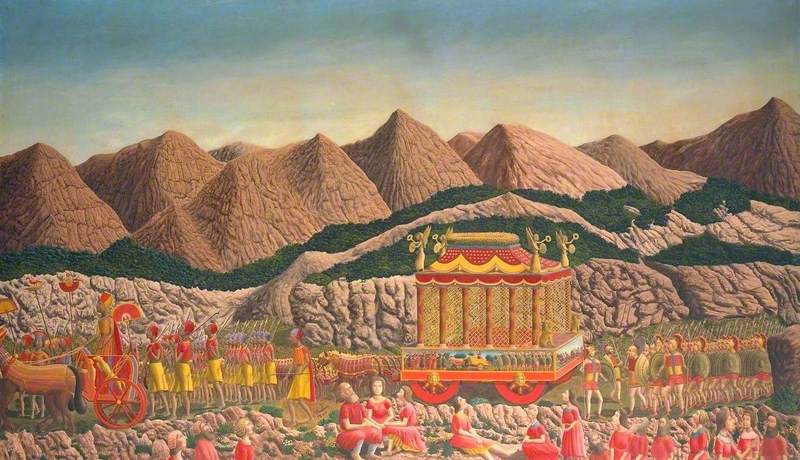

His favourite painting of all, which always hung over his bed in London, was The Funeral Procession of Alexander the Great by the French naïve painter André Bauchant, left to Tate.

The Funeral Procession of Alexander the Great (Les Funérailles d'Alexandre-le-Grand)

1940

André Bauchant (1873–1958)

Jeffress championed European naïve painting; he also adored military parades for spectacle and eroticism. As well as art, he left money to a sailors' charity: for male ratings only for all the pleasure that they had given him throughout his life.

Gill Hedley, writer and curator

Gill's book Arthur Jeffress: A Life in Art is available now, published by Bloomsbury