'We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.'

– T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets, 1943

There is something reassuring about gazing at a landscape painting. Visitors to Dulwich Picture Gallery often comment on how pleasant it is to sit for a while and to be transported on an imaginary walk alongside a rushing waterfall by Jacob van Ruisdael; to enjoy a sunrise created by Claude-Joseph Vernet simply with oil paint on canvas; or to luxuriate in the 'sound' of the wind through one of Gainsborough's trees in the backdrop to Elizabeth and Mary Linley.

Elizabeth and Mary Linley

c.1772 (retouched 1785)

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

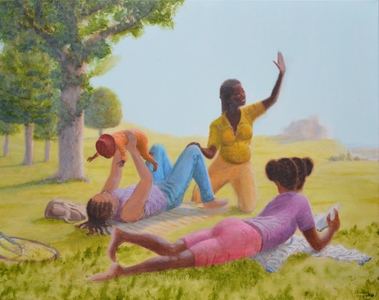

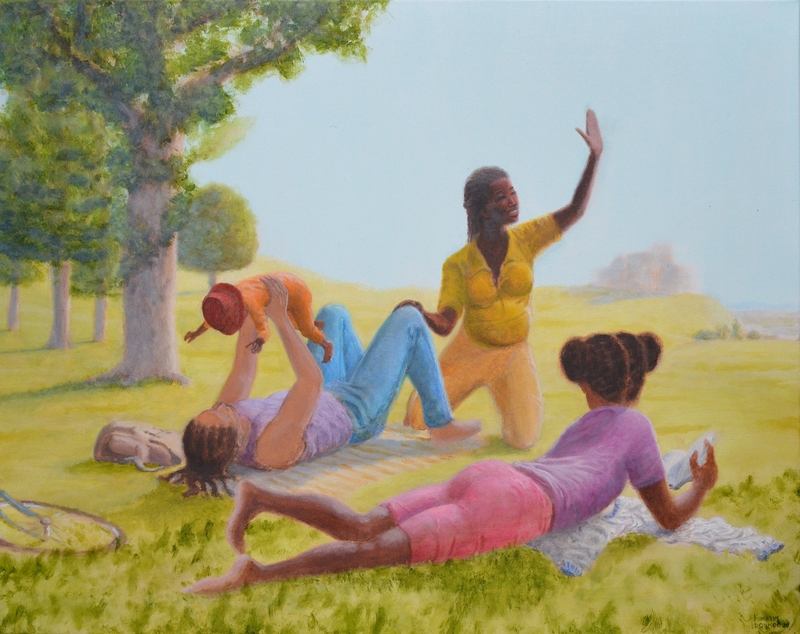

Our spring exhibition at the Gallery, 'Soulscapes' presents works by leading contemporary artists from the African diaspora that question our relationship to the land and the histories that landscapes hold for each of us personally. The jumping-off point for this concept was the strength of the landscapes within the Dulwich Picture Gallery collection itself. These historic paintings might appear to be lovely escapes from reality, but are they solely objects of beauty for quiet contemplation? And do they truly speak to everyone?

Originally, the genre of landscape painting developed from religious paintings. We can see from The Fall of Man, painted by a Flemish artist around 1520–1530, that the figures of Adam and Eve dominate the scene: oversized in the foreground, and repeated in miniature in the background being chased out of Eden by an angel. The meaning of the story is enhanced by the landscape: in the background, we get a gorgeous view of Eden with sun-capped hills and verdant fields to highlight the paradise that the foolish couple will lose. In the foreground, the scratchy roots of the tree and a few carefully strewn pebbles allude to the rocky path of the sinful, mortal life that lies ahead.

As a result of the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s, which favoured the written word over religious imagery, the tradition of the outdoor setting revealing a moral message continued without the protagonists (such as Jesus, the Virgin Mary or Adam and Eve) needing to be included.

In A Mountain Path of c.1645–1650 by the Dutch artist Jan Both, we see a rocky path in the left foreground. Cowherds and travellers alike have to traverse this land, and to navigate around the twisted tree trunks and over the crags and hills before escaping into the bright, idyllic sun-drenched distance. It is a metaphor for the hardships of life and the reward that comes in the wake of virtuous toil. The land holds the meaning, while simultaneously being attractive to look at. Therefore, landscape paintings provided a new way for incorporating uplifting moral messages in art without overt religious symbolism. For artists based in the Protestant Dutch Republic (as opposed to the Catholic Southern Netherlands), landscapes secured a vital source of commissions when the previously lucrative market for altarpieces had dwindled.

Authors are often advised to 'write what you know'. When it comes to artists, it is of course difficult to paint what you have not seen. In the seventeenth century, many artists from Northern Europe travelled south to witness new things, most famously the golden light of Italy, the drama of Classical ruins, and the craggy heights of mountain ranges.

Landscape with Travellers Resting (A Roman Road)

1648

Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665)

Major talents such as Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain from France, Adam Elsheimer from Germany, and a group of close-knit artists from the Netherlands known as the Bentvueghels (birds of a flock) who clung to each other rather than integrating with Roman artists and gave each other nicknames – Karel Dujardin was 'Goatee beard' and Cornelis van Poelenburgh was 'Satyr' – expanded their visual repertoire through travel. It is thought that the Dutch artist Nicolaes Berchem never travelled further than Germany, but he was able to depict the warm light of Rome by copying his fellow artists, like Jan Both, who had ventured south.

There was a strong commercial market for landscape paintings during the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648). In the midst of a land-grab across Europe, where territories were heavily disputed, a bucolic view of a Flemish farm could satisfy a nostalgic yearning for peace and serve as an idealised reminder of the pride in a homeland. It is no accident that paintings made in the Dutch Republic often feature windmills or the polders (reclaimed land) – the country was proud of its trade success, and the artists creating these images cemented the vision of an ambitious, powerful nation fighting for its independence, and literally carving out its land from the sea.

Furthermore, Dutch Landscape painters prided themselves on innovation. A group of painters known as the 'tonal school', including Salomon van Ruysdael, Jan van Goyen and Aelbert Cuyp, aimed to experiment with the effects of blending colour and texture, as in Cuyp's River Landscape of c.1640 where the ripples of the water are evoked by the grain of the wooden panel of the painting itself, creating not just the landscape but the sensation of being within the view. This approach paved the way for the later experiments of J. M. W. Turner and, later still, the Impressionists.

Landscape art has always been at the cutting edge of creative practice and landscapes have the potential to hold several meanings. But historically, these can be excluding. How easy it is to write of wealth gained from the East India trading company, and to skim over the suffering of people who had no agency in the role they played as slaves. How simple it is to discuss the elegance of an eighteenth-century landscape setting for a portrait by Gainsborough and to overlook the fact that wandering aimlessly in nature was not a pastime for anybody other than the uber-wealthy.

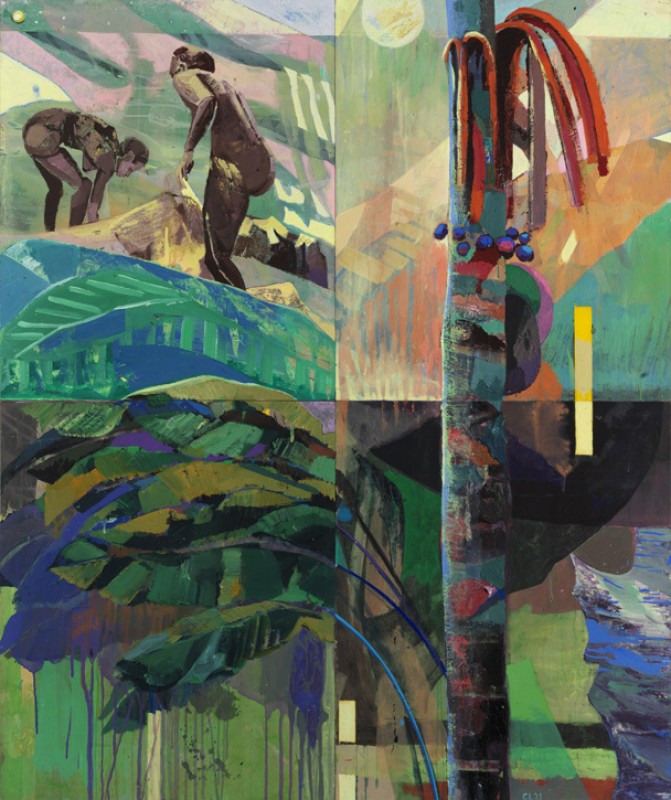

In curating 'Soulscapes', Lisa Anderson has grouped together landscape paintings in the true tradition of the genre, with the added strength of inclusivity. The artists in this exhibition pick up the baton from the landscape innovators of the past by presenting images with deep meaning and which are artistically ambitious, and they open up their perspectives and stories for everyone, making the personal universal.

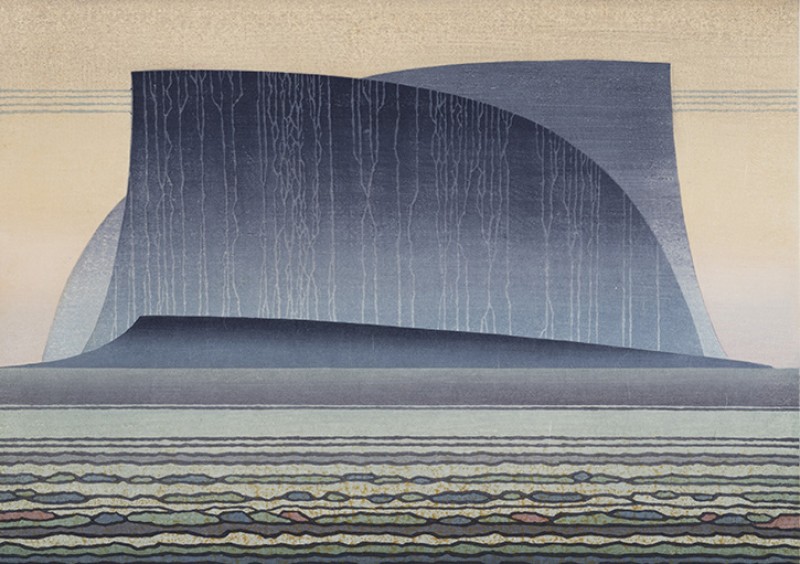

Onyx Cave (Stones Against Diamonds)

2015 by Isaac Julien (b.1960). Private collection

Michaela Yearwood-Dan's Another Rest in Peace – from a land in which we came integrates ceramic petals onto the surface of the oil painting, and it forms a diptych, like an altarpiece, as though evoking religious meditation and welcoming us all to find peace in our own way. Isaac Julien's Onyx Cave (Stones Against Diamonds) is set in the ice caves of a hard-to-reach area of Iceland. Only a few people can access this place, but Julien shows a Black figure within the snow – not only belonging within it, but also sharing the experience of the sublime vision with us all. Julien trusts in us to explore with him, through his eyes.

With 'Soulscapes', we encounter the landscapes of our time. We find comfort and challenge through them, and at the end of all our visual exploring, we might understand each other, ourselves, and our shared, damaged, beautiful world a little better, together.

Jennifer Scott, Director of Dulwich Picture Gallery

'Soulscapes' is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 2nd June 2024

This article was originally published in In View, Dulwich Picture Gallery's members' magazine

.jpg)