Few contemporary painters engage as passionately with the art of the past as Alison Watt. She is often to be found in galleries and museums looking long and hard at paintings. 'Looking back is the most important part of my practice,' she says. 'It has shaped who I am as a painter. Every body of work I've made has sprung from spending long periods of time looking at historical painting.'

This means intense and – Watt herself admits, sometimes obsessive – contemplation of specific works to which she is drawn. When she was artist-in-residence at The National Gallery in London between 2006 and 2008, it was Saint Francis in Meditation by seventeenth-century Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbarán.

More recently, there has been Venus Frigida by Peter Paul Rubens, certain photographs by Francesca Woodman and the portraits that eighteenth-century Scottish painter Allan Ramsay made of his two wives, Anne Bayne and Margaret Lindsay.

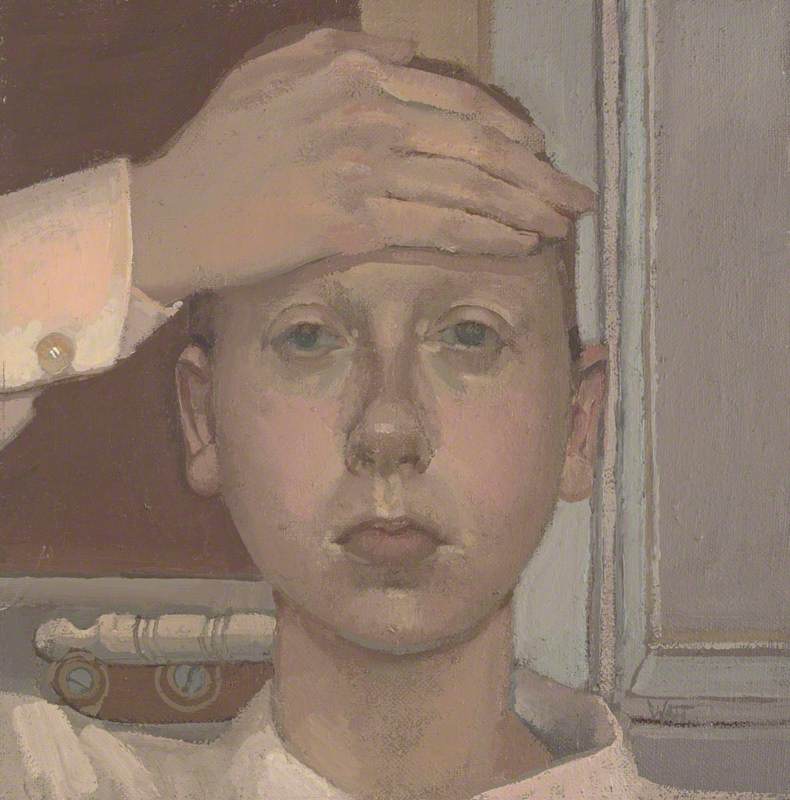

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Anne Bayne (d.1743): The Artist's First Wife c.1739

Allan Ramsay (1713–1784)

National Galleries of Scotland'When I look at a painting, it's not a one-sided activity, it's something that goes back and forth. Once I become interested in something, it becomes embedded in my consciousness, so it's almost like having a relationship with a human being, it's not static, it's something that unfolds over time. Often, I become completely obsessed by a detail in the picture. As aspect of it will catch my eye and that's the beginning of something.'

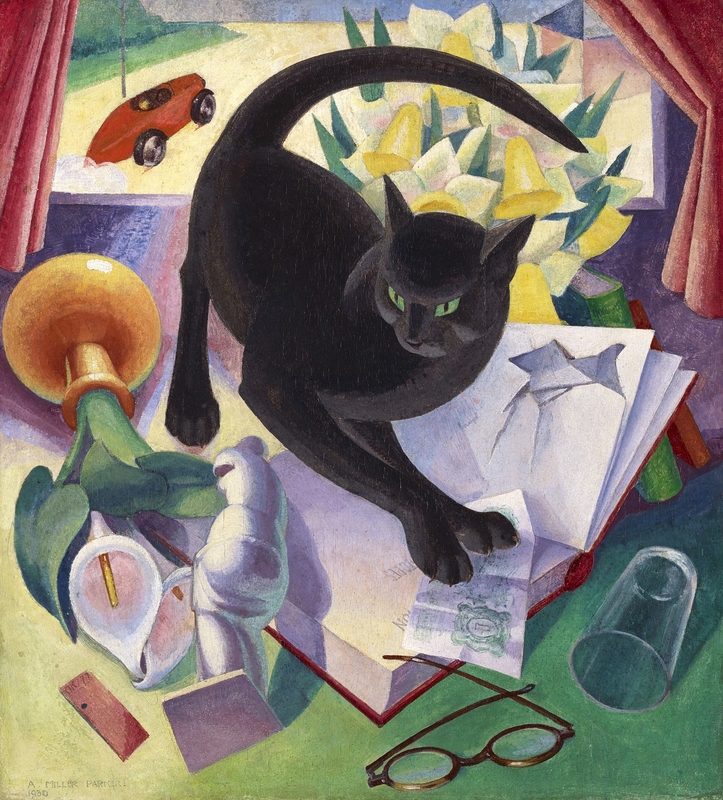

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

The Artist's Wife, Margaret Lindsay of Evelick (c.1726–1782) 1758–1760

Allan Ramsay (1713–1784)

National Galleries of ScotlandLike this. Look closely, for a moment, at Ramsay's portrait of Margaret Lindsay, how she seems to be turning momentarily from her flower arranging to respond to something her husband has said. Look how her fingers hold the stem of a rose. Look at how the stem is broken. 'Ramsay is someone who composed his paintings so meticulously, but we'll never know what that detail means,' Watt says. 'When you make a painting you are creating a private world, a painting is its own universe. A painting like that will remind you how mysterious painting is.'

A chance conversation about these paintings with Julie Lawson, chief curator of portraiture at the National Galleries of Scotland, led to Watt being invited to spend time with Ramsay's archive at NGS and produce work in response. 'A Portrait Without Likeness: A Conversation with the Art of Allan Ramsay' at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery includes the two Ramsay portraits, a selection of his drawings and 16 new paintings by Watt. 'Initially I thought I might make one work, and I made 16 works, so it just grew, the work just flowed.'

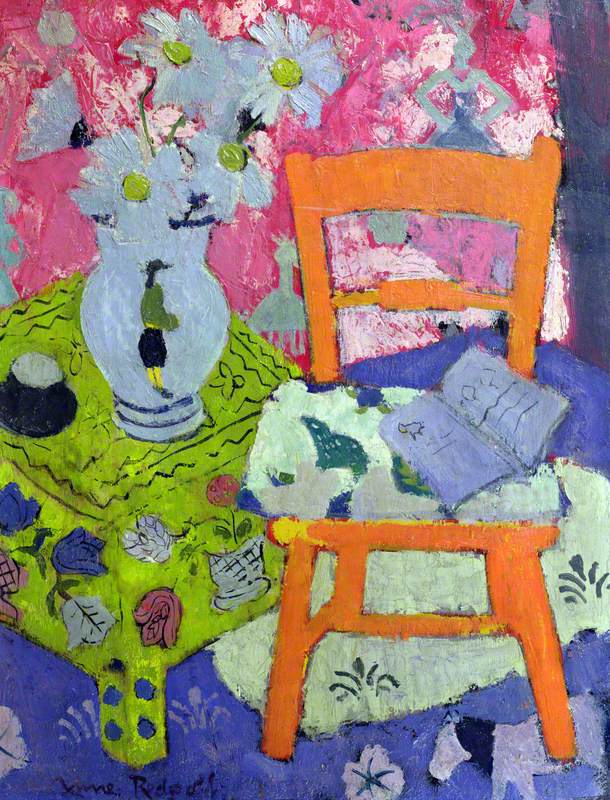

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the artist

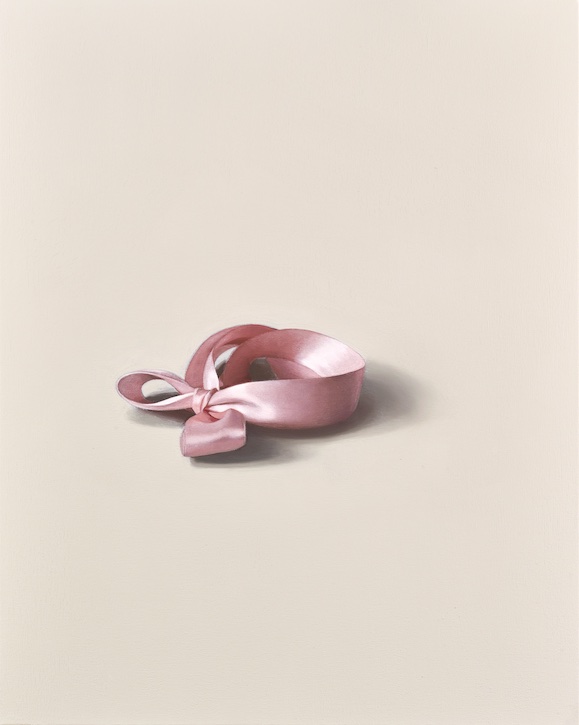

Anne

2019, oil on canvas by Alison Watt (b.1965)

The new paintings isolate details from Ramsay's portraits of women, not only his two wives but other women he knew well – clever, articulate women who hosted salons and discussed art, literature, politics, who shaped his ideas even as he painted. She picks out Anne Bayne's pink ribbon choker, Margaret Lindsay's rose, a book from his portrait of Caroline Fox, the much-speculated-upon cabbage leaf which Ramsay depicts in the hand of Frances Boscawen (both now in private collections), a lace collar for Anne, Countess of Balcarres. Removed from their context, the objects become starting points for new narratives.

'I'm fascinated by the relationship between the genres of still life and portraiture,' says Watt. 'I think still life can be incredibly intimate. Because we attach so much meaning and significance to objects, they reflect us. They are a form of biography. As far as I'm concerned, the still life is a portrait without likeness.'

It was portraiture that first fascinated her. As a child of seven, on her first visit to The National Gallery with her artist father, James Watt, she was enchanted by Ingres' portrait of Madame Moitessier. 'Then, as many young artists are, I was obsessed with self portraiture. I would stand in front of a mirror and paint myself endlessly. I think we love looking at portraits because we love looking at ourselves, we love looking at each other. But the longer I painted for, the more I started to question what portraiture was actually for, what it was about.'

At Glasgow School of Art, she excelled at figurative painting. In 1987, the year before she graduated, she won the John Player Portrait Award (the forerunner of the BP Portrait Award), which led to a commission to paint the Queen Mother for the National Portrait Gallery.

However, in the late 1990s, Watt began to focus her attention on drapery rather than figures. Her work became about swathes and folds, knots and shadows, poetic, sensual paintings, some poised on the edge of abstraction, others suggestive of human presence. Her solo exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 2000, appropriately titled 'Shift', marked what felt like a permanent shift away from the figure.

Are these precise, delicate paintings of objects to be seen as a significant departure, even a new direction? Not for Watt. 'In my very early paintings, there are very strong elements of still life. I can find elements of what I'm doing now scattered throughout the work I have made before. The paintings themselves may look different but, to me, they're all coming from the same place. In some ways, I've been ploughing the same furrow for decades, it's just presented itself in different ways.'

Take Anne, the painting of the ribbon choker worn by Ramsay's wife Anne Bayne. Separated from its context, the choker describes the curve of Bayne's neck; she becomes powerfully present, even though she is absent. Watt experienced something similarly powerful when she purchased an eighteenth-century lace collar so she could handle it before painting one. 'As soon as I unwrapped it, it was in the shape of the neck. It vibrated with the presence of something from the past. I couldn't keep it out for too long because it slightly freaked me out as an object, it seemed to be so imbued with the person who had worn it.'

That's not to say that the lace collar she paints in her new painting Balcarres is that lace collar. 'The work tends to be a combination of found imagery, invention, memory and lengthy descriptions in my sketchbooks. The paintings look like direct representations, but the more you look at them you might notice inconsistencies, the placement of shadows might be arbitrary, or the scale is wrong. You are lulled into a false sense of security because you think you know what you're looking at.'

And so we are back with mystery. For Watt, even her own painting is mysterious. It is an act of inquiry, exploration, but one from which she always returns with questions rather than answers. Spending time with Allan Ramsay's sketchbooks has left her with a powerful sense that he was grappling with something similar.

'Time just seemed to disappear when I held the sketchbooks, and that was electric. From what I could decipher from his writing, which was about the use of colour and paint, the struggles which he was encountering with the medium and with his own work were struggles that would be encountered by a painter in the twenty-first century. He was feeling the things that painters now feel.

'Looking at the sketchbooks, I was so aware that being a painter is being part of a tradition, something much bigger than yourself. Ramsay knew it, I know it, any painter knows it, you're part of a cycle of looking and making. Ramsay is looking back, including drawings by Rubens and Van Dyck, and I am looking back at him.

'I don't understand painting. I certainly don't understand my own painting, and I feel like I'm on this journey of constantly trying to find out. Ramsay's sketchbook proves that he's trying to find out, even if he is not always sure what he's looking for.'

Susan Mansfield, writer and journalist

'Alison Watt: A Portrait Without Likeness' is showing at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh from 17th July 2021 to 9th January 2022

This content was supported by Creative Scotland