My new book, Storyland: A New Mythology of Britain, retells medieval myths and legends of Britain as if they could be strung together as one long story.

It's here! @amy_historia's beautifully illustrated new mythology of Britain #STORYLAND hits bookshops today

— Quercus Books (@QuercusBooks) September 2, 2021

Grounded in research told as fiction and adorned with original linocut prints, this is a truly magical addition to any bookshelf https://t.co/m8n0bbLEOJ pic.twitter.com/iWux7VGBt0

I have sought, as well, to bring a modern voice to their textual narration and linocut illustration. Artists before me have interpreted these stories, reflecting the styles, forms and predilections of their age. In their work we see everything from the neo-Baroque of the Victorian era to Brutalism.

Let us start with a luxurious oil painting of King Lear (legendary founder of Leicester), in conversation with his daughters.

Here the costume and architecture are Italianate and Lear's pose is judicial, even Solomonic, imbuing a British myth with the aura of the Old Testament and the classical world.

Herbert's painting is comparable in style to William Calder Marshall's nineteenth-century bronze sculpture Sabrina Being thrown into the River Severn.

Sabrina Being Thrown into the River Severn

1880

William Calder Marshall (1813–1894)

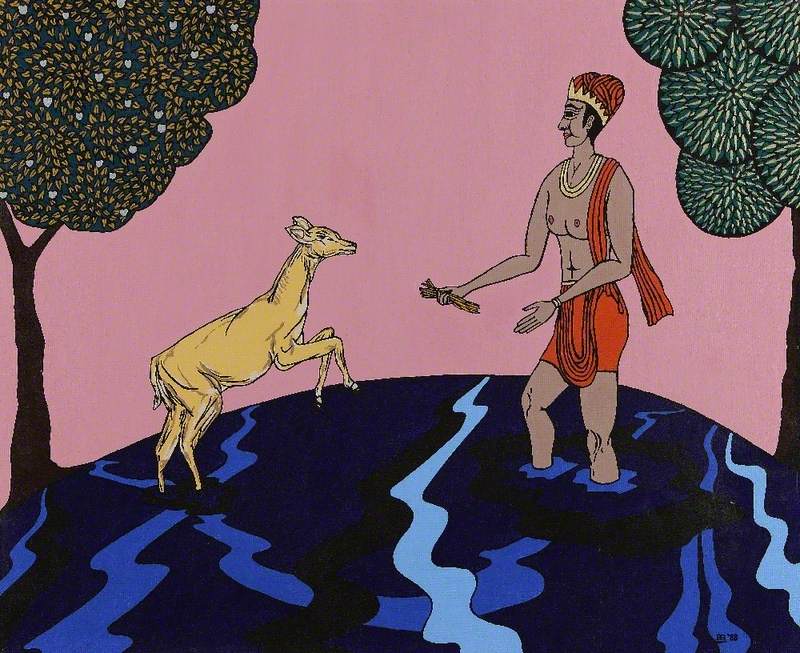

The story of Sabrina, drowned alongside her mother by her father's ex-wife, Gwendolen, is found in Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain (c.1136). The sculpture, with its sinuous nude forms, has something of Bernini's Baroque marble rendering of Apollo and Daphne (1622–1625) from Greek myth, in the Galleria Borghese.

View this post on Instagram

Likewise, William Goscombe John's bronze depicting Merlin holding the infant King Arthur (probably late nineteenth century), not only utilises a medium beloved by Renaissance artists, but recalls the Christian iconography of Saint Simeon, recognising the divinity of the Christ Child in the Temple, and that of Saint Christopher, carrying the infant Christ.

Merlin and Arthur / Myrddin ac Arthur

1902

William Goscombe John (1860–1952)

Merlin is the character in several medieval versions of the Arthur myth who, marking the child for kingship at his birth, devises the sword in the stone. The old sage's beard, robes and bare feet are as much biblical as they are druidic.

In these and other nineteenth-century reinterpretations of episodes from medieval myths of Britain, Renaissance-era media, iconography and style lend authority. Perhaps they reflect the concerns of a polity with imperial ambitions, eager to use ancient tales to assert royal pedigree or at least foster a sense of national pride.

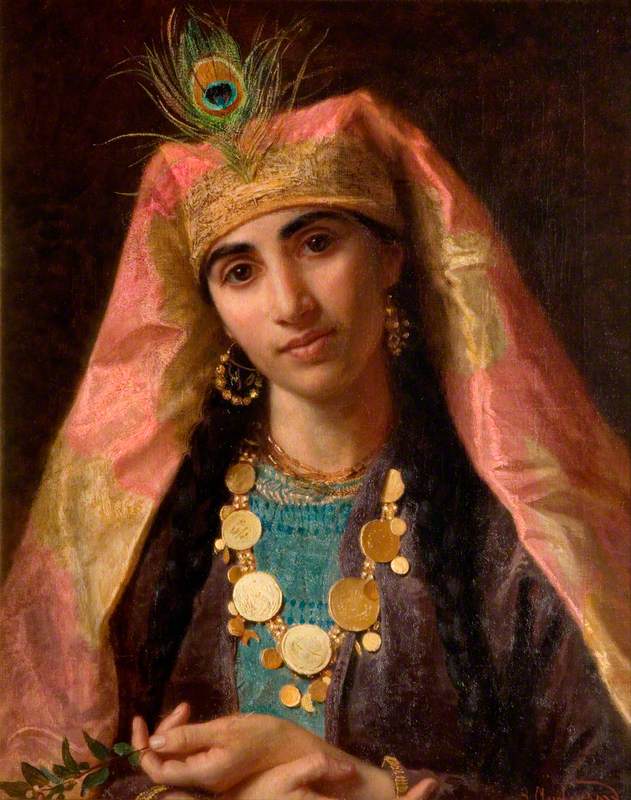

Other artworks that may operate in this way are Saint Columba Rescuing a Captive by Robert Inerarity Herdman and Arlète, a Peasant Girl of Falaise in Normandy, First Discovered by Duke Robert le Diable by Paul Falconer Poole, which shows William the Conqueror's mother and father.

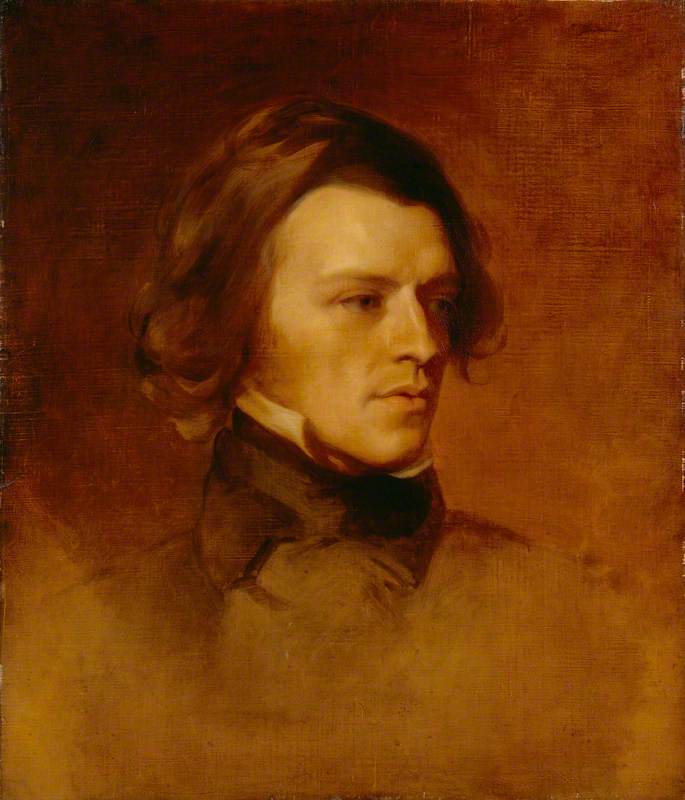

Arlète, a Peasant Girl of Falaise in Normandy, First Discovered by Duke Robert le Diable

1848

Paul Falconer Poole (1807–1879)

Another example is Andrea Casali's Edward Martyr Being Stabbed in the Back in the Presence of Elfreda at Corfe Castle about the death of the King of the English, Edward the Martyr. It is the work of an Italian artist who spent 25 years in England and specialised in historical, mythological and biblical subjects.

Edward Martyr Being Stabbed in the Back in the Presence of Elfredo at Corfe Castle

1761 or before

Andrea Casali (1705–1784)

In contrast to their nineteenth-century predecessors, artists of the twentieth century and beyond have treated myths and legends of Britain with less classicising grandeur. Take, for instance, Patrick Hayman's 1962 tempera depiction of Lear and Cordelia, in which father and daughter are eerie figures: he a black-clad, magisterial focal point, and she a pastel smudge with a benign smile.

While the tempera medium is that of medieval panel paintings, the painting has the brazen naivete of twentieth-century Modernism. It appears to reflect the interior worlds of the characters and the tension of their relationship.

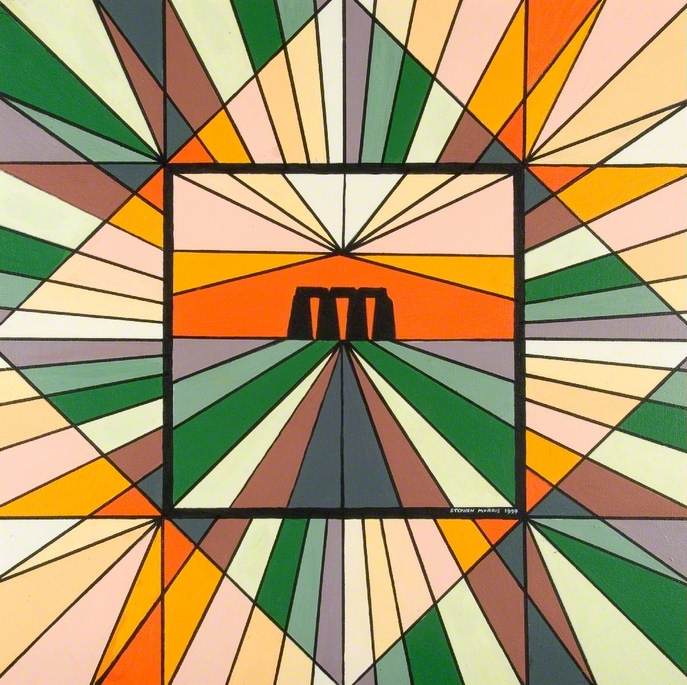

Boldly abstract, the Coranieid by Selwyn Janes-Hughes takes its inspiration from the Welsh Mabinogion.

The title refers to the fairy race said to have been the first of three plagues to afflict Britain in the reign of King Lludd. The race has hearing so perfect that no plot to oust them can be hatched in secret. Viewed through the lens of the story, the panels of gold, blue, brown and black enamel with jagged edges create impressions of a physical and psychological landscape torn and fractured by invasion.

When it comes to more conventionally illustrative post-nineteenth-century depictions of subjects from British myth, the context is frequently civic or ecclesiastical. Saints – often the subject of local legend – may be shown with attributes from their stories and come to serve as local mascots.

A case in point is Saint Mungo, alias Kentigern, founder and patron saint of Glasgow, one of whose numerous miracles is said to have been to save the life of the king's adulterous wife by finding her ring in the stomach of a fish. Mungo's fish, along with motifs from three other miracles, is shown before the saint in a glistening metal sculpture produced in 2001–2003 by Eduard Bersudsky and the Sharmanka Kinetic Theatre.

The figure resides on Trongate, one of the oldest streets in Glasgow and thus animates the civic space with the city's legendary founder.

Moving south, Warwick's local hero, Guy of Warwick, is commemorated in a sculpture of the knight alongside a boar he is said to have defeated. Standing on Guys Cross Park Road, the brutalist aesthetic and use of cast concrete take on new meaning in the light of the work's patronage: it was commissioned from Keith Godwin in 1964 by the Annol Development Company, who developed and sold real estate. It was then presented by that company to Warwick Council.

All the stories I have mentioned so far are medieval. This antiquity may also be what makes them so compelling. One piece in particular showcases the artistic potential of the passage of time. Prince Bladud & Pig was assembled by Nigel Bryant and City of Bath College Students in 2009 and stands in Bath's Parade Gardens.

Prince Bladud and Pig

1859 & 2009

Stefano Valerio Pieroni (c.1817–1900) and Nigel Bryant (active 2009) and City of Bath College Students (active 2009–2014)

The larger part of the piece is a nineteenth-century sculpture of the city's legendary founder, King Bladud (father of King Lear) by Stefano Valerio Pieroni. The rest was created in 2009, 150 years later, and constitutes a pedestal and one of the pigs whose spotless skin, legend has it, led Bladud to find a cure for his leprosy in the warm mud generated by the valley's thermal springs. Both pieces are made of Bath stone. They thus highlight the longevity of the story, not only by juxtaposing old and new but by means of the ancient stone through which the city's famous waters run.

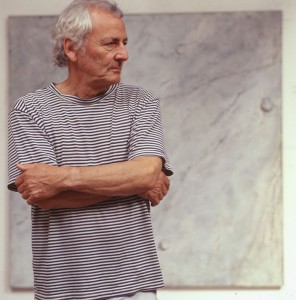

My survey here only scrapes the surface. Artists have long engaged with the stories that populate the island of Britain with beings, beasts and bards, and they will continue to do so. And with each new treatment we will have fresh opportunities to learn about the interests of contemporary British society, ever-changing for all its unfathomable age.

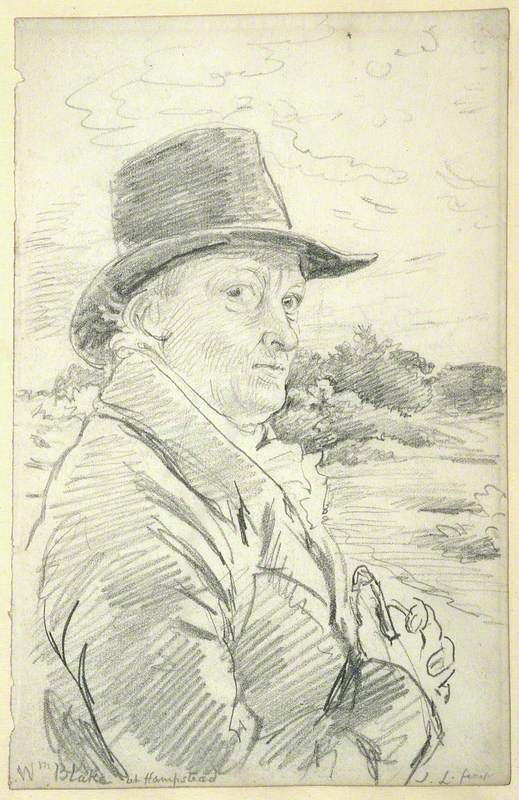

Amy Jeffs, art historian and printmaker

Amy's book Storyland: A New Mythology of Britain, published by Quercus, is out now

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.