Since the reopening of the National Portrait Gallery in June 2023, following a refurbishment involving a complete re-presentation of its collection, 13 'Kit-Cat' portraits by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) can be viewed in Room 8.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Installation view of the Kit-Cat Club portraits by Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

Room 8, National Portrait Gallery, London

But this is only a portion of the 42 extant paintings in the full series, depicting the members of a notable Club which lasted from the mid-1690s to around 1720. Taken as a whole, it constitutes an impressively large group of elegant, bewigged gentlemen, expressive of the thoroughly male world of early eighteenth-century club culture.

Regrettably, no official records of the Kit-Cat Club survive, but it seems to have developed informally at first, before becoming a highly influential organisation for promoting both the policies of the Whig political party and various artistic and literary projects. One of the Club's founders, and its first Secretary, was Jacob Tonson (1656–1736), an important publisher of the works of William Shakespeare (1564–1616), John Milton (1608–1674) and John Dryden (1631–1700).

In his own Kit-Cat portrait, he clasps the illustrated fourth edition of John Milton's Paradise Lost which he had published in 1688, helping to secure his fortune and reputation.

Other important early members were Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset (1643–1706) and John Somers, Baron Somers (1651–1716).

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset c.1697

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonAt its height, the Kit-Cat Club totalled an impressive roll-call of major Whigs, from landowners and statesmen, through financiers, diplomats and military figures involved in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), to writers and playwrights.

This was the heyday of the numerous gentlemen's clubs which arose following the so-called 'Glorious Revolution', especially in London. The historian Peter Clark has called the Club 'one of the most distinctive social and cultural institutions of Georgian Britain'.

We are provided with an account of a selection of these organisations in satirical writer Ned Ward's Secret History of the Clubs (1667–1731), published in 1709. Ward tells us that the Kit-Cat's curious name derived from the fact that the Club would meet in a tavern on Gray's Inn Lane, London, kept by a pastry cook named Christopher Cat under the sign of the 'Cat and Fiddle'. However, other contemporary sources link the title to Mr Cat's famed mutton pies, known as 'Kit-Cats'. These provided sustenance to the Club members when they met to dine, drink and discuss the affairs of the day.

Other taverns in London and Hampstead played host across the years, but, in 1703, Tonson acquired a new house at Barn Elms, on the south side of the Thames near Putney, and this became a key meeting place. Architect Sir John Vanbrugh (1664–1726), another member of the Club, redesigned the interiors of Barn Elms, and it was here that Kneller's portraits were first displayed.

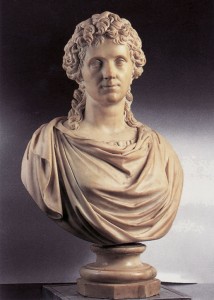

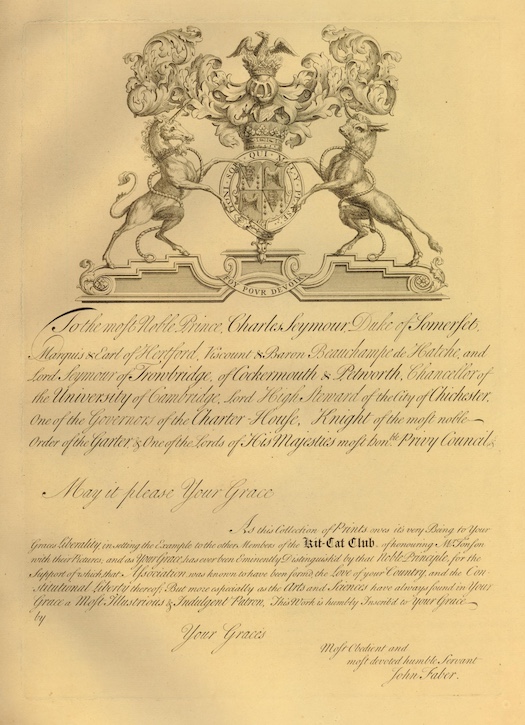

They were painted one by one, each commissioned as a gift from the sitter to Tonson. When the printmaker John Faber the younger (c.1684–1756) later dedicated his series of mezzotints after Kneller's portraits to the Kit-Cat Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset (1662–1748), he credited him with having started this tradition of the Club members 'honouring Mr. Tonson with their Pictures'.

Image credit: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Lettered dedication to Charles Seymour with a note on the Kit-Cat Club

1731–1735, engraving on paper by John Faber the younger (1684–1756)

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset c.1703

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonThe commissioning process was slow and gradual, extending across the Club's full lifespan. On 15th June 1703, Vanbrugh wrote to Tonson, who was away in Holland on publishing business: 'the Kit-Cat wants you, much more than you ever can do them. Those who remain in towne, are in great desire of waiting on you at Barne-Elmes; not that they have finished their pictures neither; tho' to excuse them (as well as myself), Sr Godfrey has been most in fault. The fool has got a country house near Hampton Court, and is so busy about fitting it up (to receive nobody), that there is no getting him to work'.

Kneller's canvases were later hung in a special room at the property built by Tonson's nephew and heir, Jacob Tonson II (1682–1735), and they remained with the family until acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 1945.

The Kit-Cat Club was highly influential in promoting Whig policies such as contract theories of government and the rights of religious nonconformists; critical while the party was in Opposition to the Tories during the reign of Queen Anne (1702–1714).

Kneller's long-time studio assistant and drapery painter, John James Baker (c.1648–1712), executed a group portrait of the Whig leaders in this period – known as 'The Whig Junto' – together with a Black servant who serves to further emphasise their power and elevated social status. Four of the six sitters shown here were also Kit-Cats.

However, the Club was also about developing the 'soft power' of Whig values. This sometimes meant direct patronage of the arts. Members of the Club, for example, contributed around £100 each towards the building of the Queen's Theatre, Haymarket, in 1705, to promote opera. On other occasions, it was more about networking, as shown by the substantial number of architectural commissions which Vanbrugh undertook for his fellow Kit-Cats.

One of the most significant examples was Castle Howard, designed for Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle (c.1669–1738) between 1699 and 1702.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle c.1700–1712

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonBut this was also cultural patronage in a more diffuse form, the Kit-Cats broadly promoting Whiggish values of politeness and civility firmly associated to this day with the periodicals The Spectator and The Tatler, published by writers Joseph Addison (1672–1719) and Richard Steele (c.1671–1729).

Those values are amply expressed in Kneller's series. To be polite meant being 'complaisant' in conversation, accommodating an interlocutor's interests, and not being overbearing if speaking with someone of a lower social status. While the portraits span middle-class and aristocratic sitters, their emphasis is on parity and homogeneity, reinforced by their standardised matching frames. One would be hard-pressed to arrange these images according to social hierarchy from appearance alone.

Steele, for example, is shown in a full, long wig, while Charles Fitzroy, 2nd Duke of Grafton (1683–1757) wears an informal soft cap over his shaved head.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Charles Fitzroy, 2nd Duke of Grafton c.1703–1705

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonRecent conservation revealed that Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Richmond and Lennox (1672–1723) originally had a cap before a decision was made to repaint.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Richmond and Lennox c.1703–1710

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonSettings throughout are minimal, and only a minority of portraits include an identifying object or sign of office: the dividers and badge of the Clarenceux King of Arms in Vanbrugh's portrait are unusual.

The dominant impression is of equal, elegant gentlemen, their broadly delineated velvet costumes providing a generalised air of 'quality', their tilted heads and elegantly splayed hands emphasising accommodating gentility. This sense of affable sociability not only extends between the portraits, but also encompasses the viewer, caught between the Kit-Cats' variously directed glances.

And it is further underpinned by what was, at the time, a novel scale of canvas: 36 by 28 inches. Somewhat larger than the established size of 30 by 25 inches for a bust-length portrait, this meant that each sitter could be shown to the waist and their hand(s) included, while retaining the life-scale of the likeness and so a sense of presence. Kneller likely adopted this format from the work of Rembrandt (1606–1669) and his school in Holland, where he had studied, but it was strikingly new in England. It became so closely identified with this series as to be referred to as 'Kit-Cat' size from then on.

One of the many reasons for Kneller's status as the foremost portraitist of the day was his impressive productivity – or rather, the productivity of his studio, as his portraits relied extensively on the work of assistants and drapery painters such as Baker. The unfinished portrait of Richard Boyle, 2nd Viscount Shannon (1675–1740), with just the sitter's face painted in, wig and pose only lightly sketched out, indicates the portion on which Kneller himself would have focused.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Richard Boyle, 2nd Viscount Shannon c.1710

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonA particularly substantial workshop contribution has been detected in the last portrait to be executed, not long before the artist's death in 1723, and the only one which breaks with the standard format: Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne and Henry Clinton, 7th Earl of Lincoln. As well as being the only double portrait in the series, showing brothers-in-law, it includes an unusual emphasis on the sitters' elevated social status.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne; Henry Clinton, 7th Earl of Lincoln c.1721

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonLincoln wears his recently bestowed Garter star, while the setting is established as Newcastle's seat, Claremont in Surrey, through the inclusion of the Belvedere in its grounds – another of Vanbrugh's designs – in the distance. This painting was executed after the Kit-Cats had effectively disbanded. Tonson senior had retired by this time, George I had acceded to the throne (1714), and most former members of the Club now had official positions in government and at court.

Indeed, it has been convincingly proposed that this atypical work was likely executed for Tonson junior, now taken over the business and Barn Elms from his uncle, and already starting to look back on the Club's glory days.

The Newcastle and Lincoln portrait may be atypical, but it depicts one of the most typical activities of the Club: drinking. And this was the only way in which women enter this story. An established Kit-Cat practice was the toasting of ladies with short verses written by the members, their names subsequently engraved onto glasses. These were usually wives or daughters, but also other society women – as long as their Whig credentials and beauty were deemed sufficient.

Several verses, for example, were penned in honour of Lady Anne, wife of the Earl of Carlisle (1674–1752), such as this ditty by Sir Samuel Garth (1661–1719), physician and poet: 'Carlisle's a name can every Muse inspire / To Carlisle fill the Glass and tune the Lyre / With his loved Bays the God of day shall Crown / Her wit and Beauty equal to his own.'

Image credit: National Trust Images

Lady Anne de Vere Capel (1674–1752), Countess of Carlisle 1690s

Michael Dahl (1659–1743)

National Trust, Petworth HouseOnly one lady, however, ever got to be present at their toast. Evelyn Pierrepont, 1st Duke of Kingston (1655–1726) had – the story goes – proposed his daughter, Lady Mary, aged only seven at the time, as the Club's toast.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Evelyn Pierrepont, 1st Duke of Kingston 1709

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonHis fellow members objected that they had never seen her, so were unable to judge her candidature. He thus ordered Mary to be 'finely dressed and brought to the tavern' where 'she was unanimously voted the reigning beauty'.

Image credit: Sheffield Museums

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762) c.1718

Jonathan Richardson the elder (1667–1745)

Sheffield MuseumsToday, the description of the little girl being passed 'from the lap of one poet, or patriot, or statesman, to the arms of another', 'overwhelmed with caresses', makes for difficult reading. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762), as she was to become, however, later declared it to have been the happiest day of her life, and it was an episode which readily caught the imagination of a number of later writers and artists, such as Andrew Carrick Gow (1848–1920).

Kate Retford, Professor of History of Art at Birkbeck, University of London

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation