Throughout history, artists have responded to new cultures in exciting and innovative ways. Whether through travel, witnessing the arrival of a foreign painter in their midst or being called upon to bear witness to cross-cultural events, artists make visible the networks that connect them to others across space and time.

In 1479, for example, Gentile Bellini (1429–1507) travelled to the Ottoman capital Constantinople (now Istanbul) as part of Venice's peace negotiations with Sultan Mehmet II following a lengthy war.

Bellini, one of Venice's most prestigious artists, visited the city to paint the 50-year-old Sultan's portrait. The court teemed with scholars and artists from across the Ottoman empire. Bellini painted the Sultan as if he was seated on a balcony, behind a parapet. The new science of perspective informs the arch above the Sultan's head and the jewelled rug placed over the parapet seeks to trick the eye into believing he sits in a three-dimensional space.

Let's compare this to another portrait painted in the same year by the fifteenth-century Turkish artist Nakkaş Sinan Bey.

Sultan Mehmed II Smelling a Rose

c.1480, illustration by Nakkaş Sinan Bey (active 15th C)

In Beg's painting, the Sultan's body has been folded into the available space with little regard for naturalism. This does not detract from the painting; it operates in a different way to a Western image. Its surface is built up of flat blocks of colour and patterns – the rhythmic pleats on the kaftan and turban, the wrinkled sleeves. It follows the tradition of Ottoman and Persian miniatures, but the naturalism of the Sultan's face suggests that Beg also studied Bellini's painting.

Beg raised the Sultan's eyebrow and his ear is bent under the weight of his turban. These details arguably give Beg's version more character. Perhaps Beg had more opportunity to study the Sultan first-hand. It is widely believed that Beg copied Bellini's Constantinople paintings and drawings but perhaps the two artists worked side by side at the Sultan's court, experimenting with each other's styles.

The cross-cultural influence was certainly not one-sided: in a drawing of a scribe, Bellini included a caption in Arabic and dressed his sitter in a highly decorative velvet robe, its surface a mass of flat gold patterning.

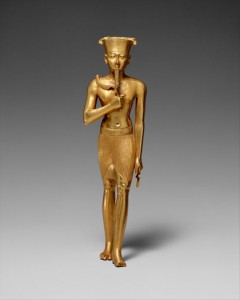

Around the time Bellini travelled to Constantinople, Portuguese merchants were exploring the coast of West Africa. They exchanged copper and brass manillas (a form of currency that looks like a chunky metal bracelet) for ivory and gold in Sierra Leone and the State of Benin. Artists in Benin used copper and brass to create wall plaques that are often known today as the Benin Bronzes.

These wall plaques record the life of the Oba, Benin's king. The Oba was always portrayed as ready for battle, the largest – and therefore the most important – person in each relief. While the plaques recorded significant battles they also marked important meetings.

The Portuguese regularly appear on these plaques, clearly identifiable by their thin faces, long straight hair, fitted tunics and pleated skirts. Hundreds of these plaques once adorned the pillars of the Oba's palace but they were looted in their entirety by British forces in 1897.

In the sixteenth century, the Portuguese also bought ivory sculptures from Benin such as this salt cellar.

Salt Cellar

c.1525–1600, carved elephant ivory made in the Benin Kingdom

African artists initially made salt cellars depicting African men, women and animals. The central sphere would open for storage but they were not intended for everyday use. Rather, they were intricately carved and highly valued art objects.

Artists responded quickly to the arrival of the Europeans and this salt cellar (above) shows Portuguese men rather than Africans supporting two spheres topped with a Portuguese ship complete with rigging and a bird's nest lookout.

Portuguese merchants exported such works back to Europe and sold them in Antwerp, their European hub for intercontinental sales. It was in Antwerp that the Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer acquired two salt cellars, paying three florins (about £500 today).

The Portuguese had ventured as far as Japan by the 1640s and enjoyed strong trade relations with the island nation. But in the early seventeenth century Japan closed its borders to foreign trade. For 250 years Japan was a closed country, so when trading resumed in the 1850s there was a strong European appetite for everything Japanese.

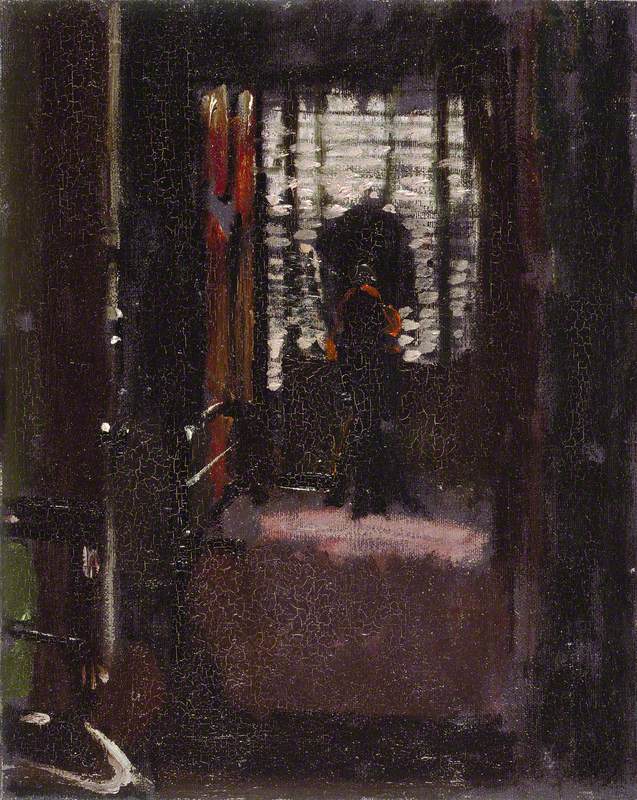

Symphony in White, No 2: The Little White Girl by James Abbot McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) from 1864 shows the extent to which Japonisme influenced Whistler's art.

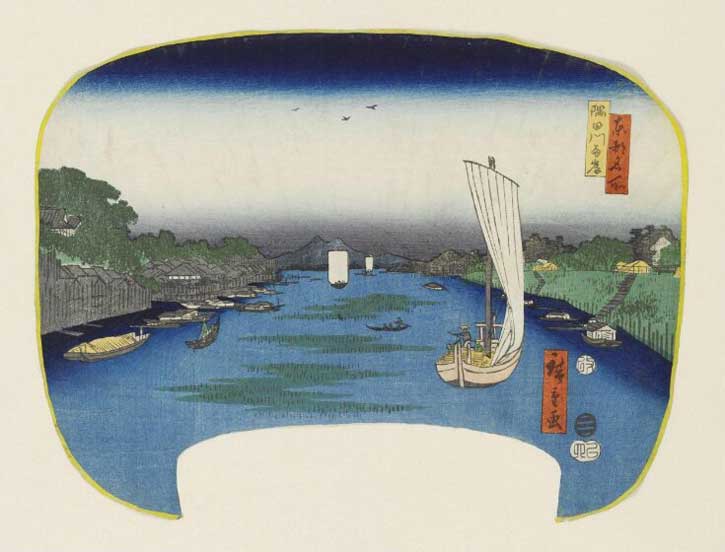

Japonisme was an obsession with anything and everything from China and Japan. Whistler – an American artist working in London – collected Chinese and Japanese porcelain and two examples can be seen on the mantlepiece in this painting. Jo Heffernan, Whistler's model, also holds a Japanese fan with this print by Hiroshige stretched across it.

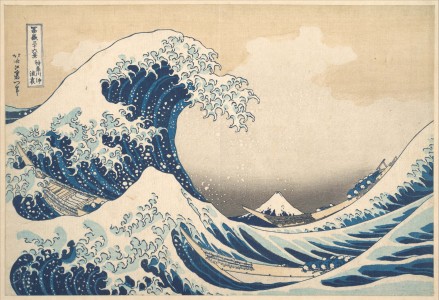

Western artists found a completely new way of thinking about landscape and the world around them by studying Japanese prints. The prints suggested new ways to turn the three-dimensional world into a flat, two-dimensional image.

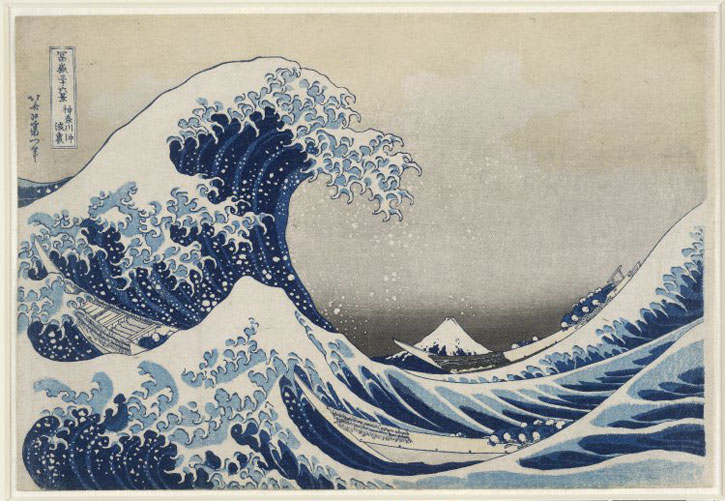

Ironically Japanese artists such as Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) had themselves been influenced by books featuring Italian vedute, eighteenth-century landscape views that employed perspective to evoke distance. This led to the new genre of prints in Japan known as ukiyo-e, or 'pictures of a floating world'.

Impressionist Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) was already familiar with ukiyo-e when she visited a major exhibition of 700 Japanese prints at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1890. She was bowled over by the show, writing to fellow artist Berthe Morisot that 'you must see the Japanese [prints] – come as soon as you can...'

Shortly after seeing the exhibition, Cassatt created a series of ten aquatints of women engaged in daily life – washing, dressing, writing letters. She responded to the flat surfaces and harmonious use of colour and patterns seen in Japanese prints such as Kitagawa Utamaro's Two Ladies from the 1790s.

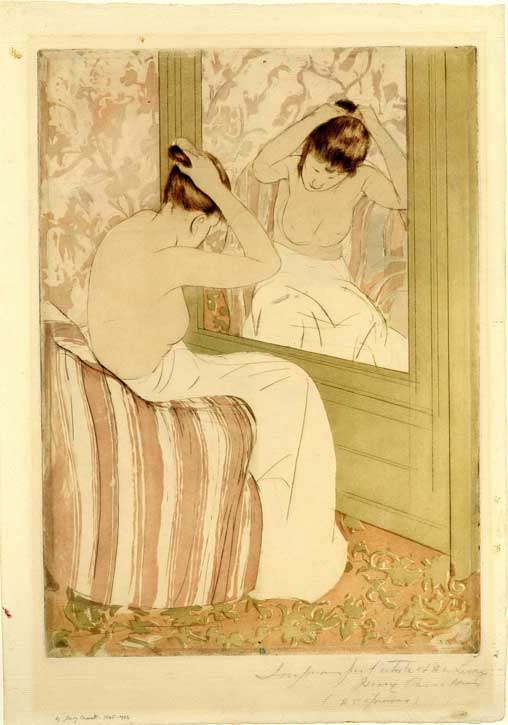

In Cassatt's The Coiffure from 1890–1891 a woman is seated in front of a mirror, naked from the waist up. She is pinning up her hair and – as in the Utamaro – we see her face reflected in a mirror.

The Coiffure

1891, colour drypoint, soft-ground etching & aquatint by Mary Cassatt (1844–1926)

This playing with surface and reflection, the spare use of colour, a flattening of the surface using pattern and a simplified sense of form points to the profound influence of Japanese prints on Cassatt's work.

These examples reveal the importance of networks to artists throughout history. Unlike the story of art, which at times has been restricted to the story of white Western men, artistic networks have always cut across borders, ethnicities, gender and generations. My book A Little History of Art follows these networks and delights in all the exciting and surprising connections they reveal.

Charlotte Mullins, author of A Little History of Art (Yale University Press)