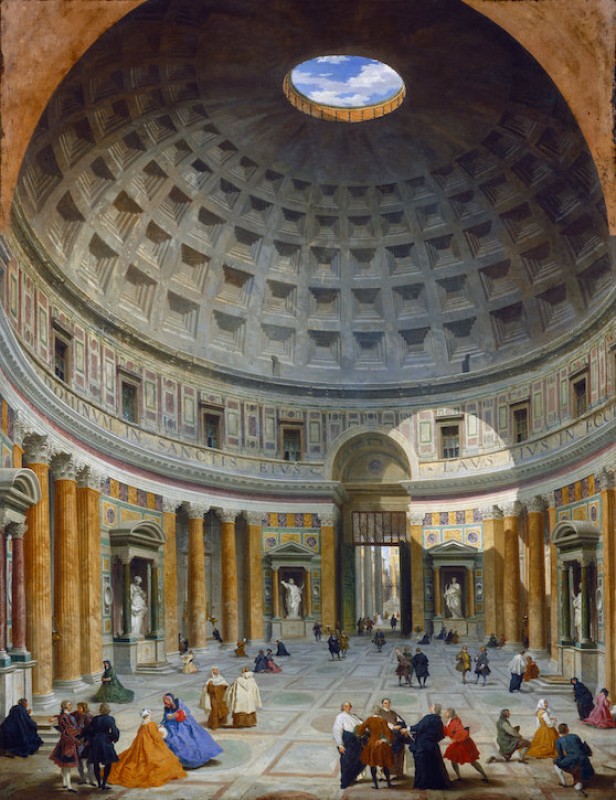

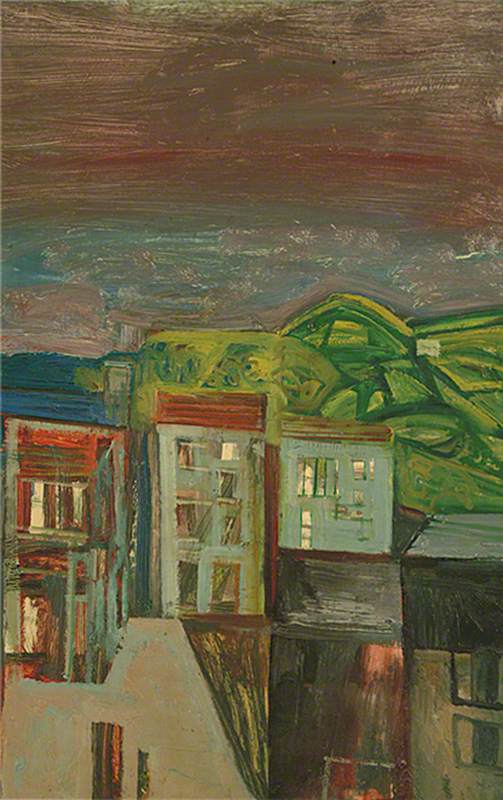

Visitors to The Red House pass from the entrance hall to a shadowed corridor that leads around corners to the drawing room. One particular painting glimmers in the dimness: John Piper's interior of St Mark's in Venice, a virtually abstract evocation of the church's domes and arches and its jewel-like decoration sparkling in the darkness.

This painting is one of many works by Piper held at The Red House, a sample of which are now made available through Art UK. In it, various themes converge, shedding light on the other Piper works in the Britten-Pears Foundation collection and on the rest of Art UK.

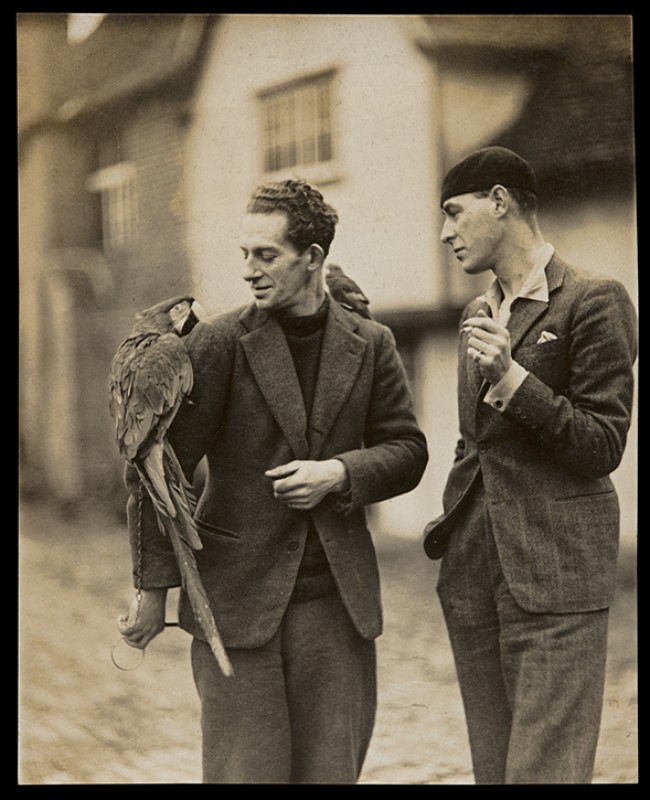

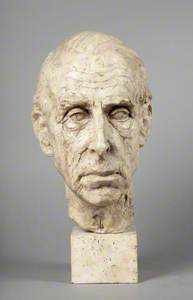

The art at The Red House was collected by the composer Benjamin Britten and the tenor Peter Pears, who moved to the house in 1957 and lived here as life partners for decades (they died here in 1976 and 1986 respectively). Pears was the main art collector of the two.

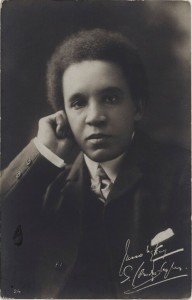

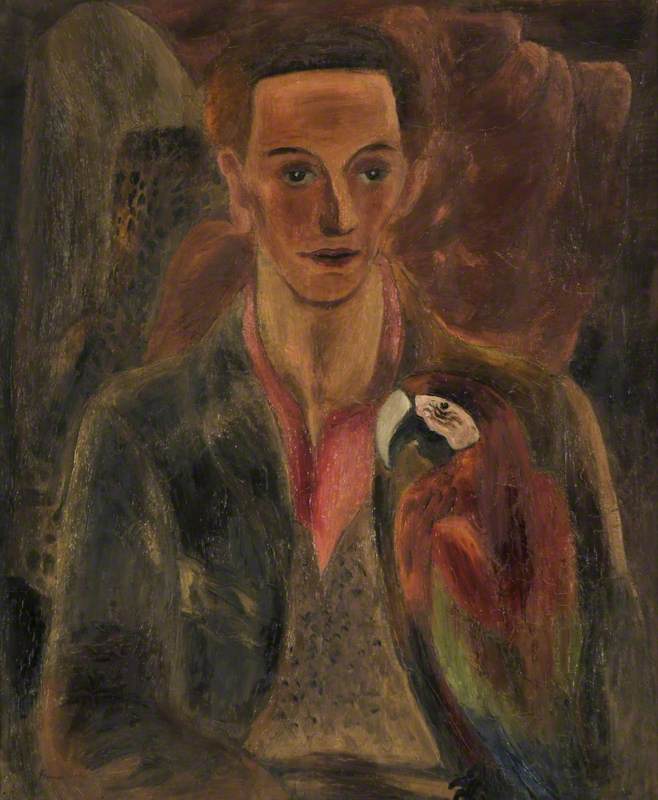

It is a very personal collection, shaped around the two men's tastes rather than any desire to create a set of works that is complete or representative: they bought what they liked, much of it mid-twentieth-century British works but also works from other countries and other centuries. In particular, personal relations bulk large in the collection: many of the best-represented artists were friends or connections of Pears and Britten, such as Mary Potter (the previous owner of The Red House), Francis Newton Souza, Christian Rohlfs (whose widow was a close friend of Pears) and Piper himself.

The connection between Britten and Pears and the painting of St Mark's goes even deeper than simple friendship. It was bought by Britten in 1973 as a Christmas present for Peter Pears. 1973 was the year in which Britten finished Death in Venice, which was to be his last opera and the last major tenor role he wrote for Pears (as the writer Aschenbach); the painting is surely a nod to this joint project. For that opera, Piper designed the stage sets and his wife Myfanwy wrote the libretto, roles that each had performed for other Britten operas before this. The painting, then, is not merely to be seen as a free-standing work of art, but as a manifestation of a collaborative creative circle.

Britten's work was embedded in his community: in one of his few explicit statements on the nature of his art – his speech on receiving the first Aspen Award in 1964 – he said 'I want my music to be of use to people, to please them, to "enhance their lives" (to use Berenson's phrase). I do not write for posterity – in any case, the outlook for that is somewhat uncertain. I write music, now, in Aldeburgh, for people living there, and further afield, indeed for anyone who cares to play it or listen to it.'

His work is, notably, often collaborative: not the result of a composer in an ivory tower writing notes for a distant posterity, but of someone working with specific musicians and a specific venue in mind, in collaboration with like-minded people from other disciplines. A composer may have an overview of what they want an opera to be like as a finished piece, but in most cases, they will delegate to others the job of writing the libretto and designing costumes and sets, quite apart from having to rely on others to sing the roles. They have to trust those others to help bring the piece to life in the way that was intended but also be aware that they, with their different expertise, may bring to it things that the composer could not have thought of themselves. Britten's work relies heavily on the presence around him of a creative circle representing many different disciplines.

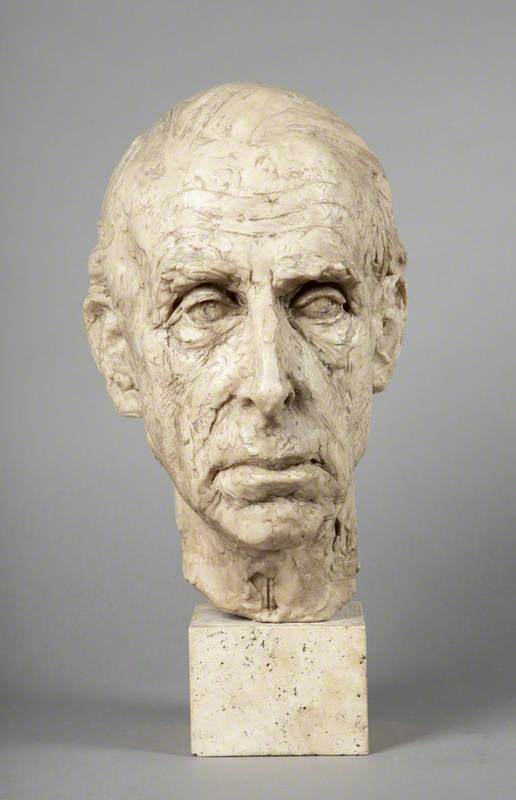

John Piper was a long-standing member of this circle and worked with Britten for over a quarter of a century, starting with set designs for Britten's 1947 opera The Rape of Lucretia. The collection at The Red House contains not merely works intended as free-standing works of art (the type of material prioritised for inclusion in Art UK) but also set designs and three-dimensional set models that mesh his work organically with Britten's. The dates of the 62 Piper items in the Britten-Pears Foundation collection (17 of which are displayed by Art UK) run from the 1930s to well after Britten's death in 1976; notably, there is the original design for the memorial window to Britten in Aldeburgh church.

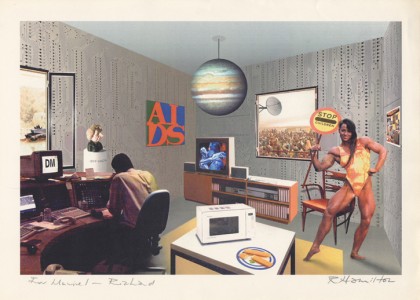

The arc of Piper's career, illustrated in the collections, is significant. In the 1930s, his work included overtly modernist elements and could take the form of abstracts and collages as well as more representational images, but representation came to dominate. His work became, like Britten's, recognisably modern without being aggressively modernist. There is also a strong commitment to applied art, beginning with his collaboration with John Betjeman on the Shell Guides to various English counties in the late 1930s and moving on to his work designing theatrical or operatic sets.

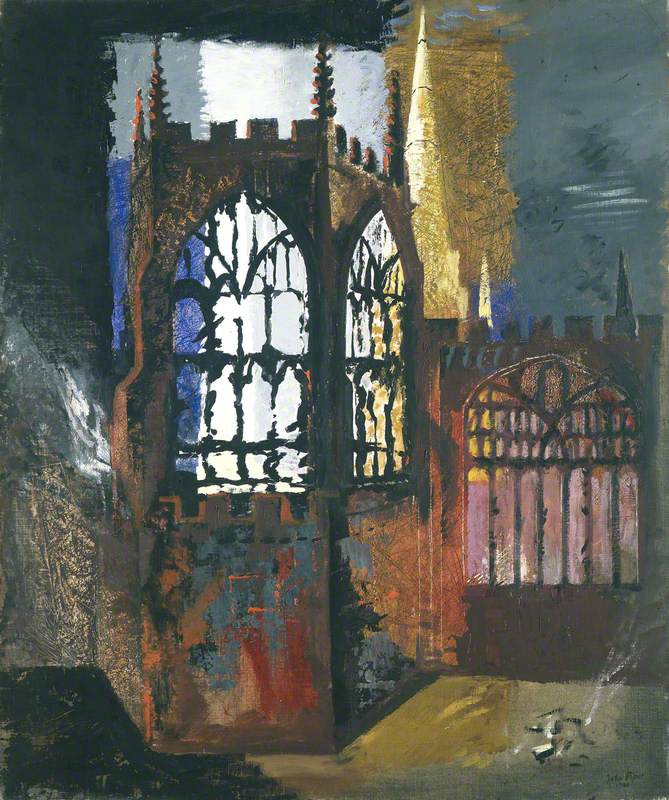

Interior of Coventry Cathedral, 15 November 1940

1940

John Piper (1903–1992)

Both Britten and Piper, of course, were involved in the Coventry Cathedral that was consecrated in 1962, replacing the medieval fabric destroyed by bombing: Piper designing the huge stained-glass window for the Baptistry, Britten composing his War Requiem for the consecration service. Sir Basil Spence's design for the building – modern, flat-roofed but retaining in its plan the essential elements of a medieval cathedral (in contrast to, for example, Sir Frederick Gibberd's 'in the round' plan for Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral) – both embodies and contains work that follows that template, of being recognisably modern but within existing forms and without departing entirely from tradition, accommodating themselves to what the viewer or listener may be familiar with and expect, fulfilling a commission to be of use within a community.

View this post on Instagram

Glimmering in The Red House corridor, the painting of St Mark's brings together several significant themes in Piper's work and in The Red House collection.

It straddles abstraction and representation, nodding to modernism whilst remaining accessible, in the same way that Britten and others in his creative circle operated.

It nods to the opera that Britten had just completed, and to the way that Piper and his wife Myfanwy formed part of the collaborative creative circle around Britten, a collaboration that is documented in the archival collections held at The Red House.

And it is rooted in friendship and personal relations, purchased by an old friend to give to his life partner as a Christmas present, an indication of the way that The Red House collection grew not as an abstract chronicle of 'great works' but as an organic reflection of friendships and personal relationships, speaking to us still of the people who lived and worked there.

Dr Christopher Hilton, Head of Archive and Library, Britten-Pears Foundation