History aficionados may well know the story of the Jacobite heroine, Flora MacDonald (1722–1790), who played a crucial role in helping Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720–1788) – known as Bonnie Prince Charlie – escape from Scotland following the Jacobite defeat at Culloden in 1746. As the story goes, Flora asked Charles to dress as her lady's maid before embarking on a boat towards the Isle of Skye. This romanticised version of the Jacobite military rebellion in Scotland – known to historians as 'The '45' – gave us the beautiful Skye Boat song, recently featured in the TV series Outlander.

Image credit: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Flora MacDonald (1722–1790)

1745–1756, mezzotint on paper by John Faber the younger (1684–1756), after Thomas Hudson (1701–1779)

In the background of this portrait, a rowing boat reminds us of Charles's escape from Scotland, hinted at by the piece of tartan that Flora holds in her left hand; in her right hand, she holds a miniature of Charles. Miniatures and portraits were among the artistic media used by the Jacobites to further their cause in the British Isles and on the continent. But who were the Jacobites, and what cause were they fighting for?

Image credit: Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

The Family of James II

1694, oil on canvas by Pierre Mignard (1612–1695)

Broadly, the Jacobites were the supporters of the senior male line of the House of Stuart to the throne of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. Their story begins in 1688. The English parliament was displeased with the conduct of James II of England and VII of Scotland (1633–1701) in matters of government and religion. Despite being the ruler of a Protestant kingdom, James had converted to Catholicism in 1669 and the birth of his son, James III/VIII (1688–1766), created the possibility of a Catholic succession.

The English parliament therefore invited William of Orange (1650–1702) – James's son-in-law – to take part in a Protestant coup, known today as the 'Glorious Revolution', which led to him becoming King William III.

But the Jacobites believed only God could choose a rightful king and James II/VII decided to fight to take back his crown.

The 119-year fight to restore the Stuarts started in Ireland. What is now referred to as the Williamite War (March 1689 to October 1691) was a series of conflicts which culminated in the Battle of the Boyne. The Irish Jacobite forces lost near the town of Drogheda on 12th July 1690.

The Cath na Bóinne is still celebrated today by Protestants in Northern Ireland: the annual march of the 'Orange Order' is considered highly offensive by Nationalists and Republicans alike.

In Scotland, the most flamboyant victory for the Jacobites took place at the Battle of Killiecrankie on 27th July 1689. On 13th April 1689, the Scottish Royal Standard was raised at Dundee, and John Graham (1648–1689), 1st Viscount Dundee led his forces to victory against General Hugh Mackay (1640–1692). Dundee led the cavalry charge at sunset down the hill and provided victory to the Scots at the price of his own life.

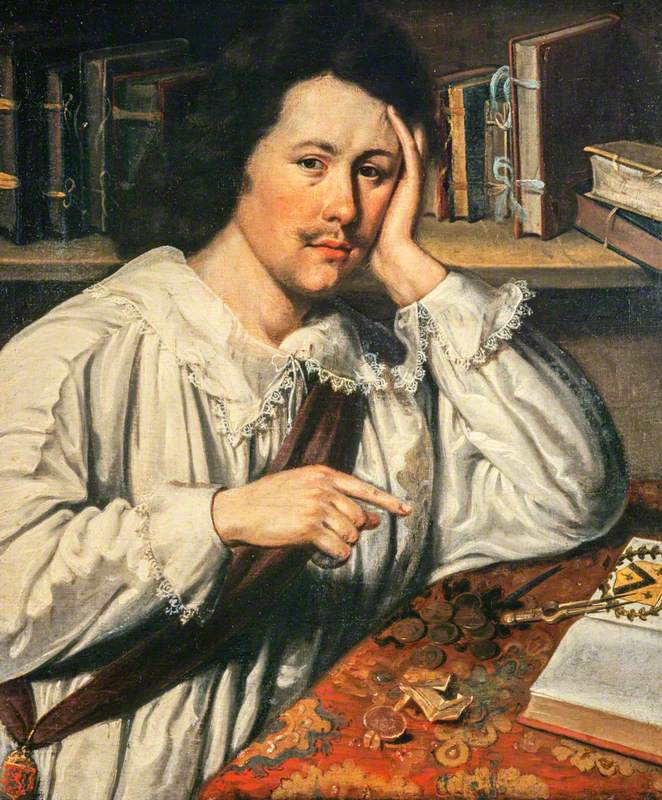

Image credit: National Trust for Scotland, Fyvie Castle

John Graham, 1st Viscount Dundee 1732

John Alexander (1686–1766)

National Trust for Scotland, Fyvie CastleAlthough the Jacobites won a battle, they did not win the war. James II and his supporters were thus forced into exile on the continent. The Stuarts first established their court in France, where Louis XIV (1638–1715) – James's cousin – welcomed them at the Palace of St Germain-en-Laye. From France, the Jacobites had to find ways to compete with the London-based de facto government and used art to constantly assert their de jure right to the throne of the three kingdoms.

Portraits of the exiled monarchs, as well as their circulation as engravings and pocket-size miniatures (such as the one held by Flora MacDonald), were one of the cornerstones of a complex multimedia pictorial war of propaganda.

Image credit: Highland Council

Prince James Francis Edward Stuart (James III) (1688–1766), 'The Old Pretender'

Alexis-Simon Belle (1674–1734) (attributed to)

Highland CouncilThe Stuarts had to fight off the rumours that James III/VIII was not the legitimate son of James II/VII and Mary of Modena (1658–1718). To further justify the outcome of the 'Glorious Revolution', anti-Jacobite publications put forward the idea that baby James had been snuck into the Queen's chamber in a bed-warming pan, and therefore might not be the real son of the King and Queen. The aim was to cast doubt on the filiation and legitimacy of James II/VII's son, whom the Jacobites styled as James III of England and VIII of Scotland after his father's death in 1701.

For this reason, the Jacobites spared no expense in having themselves depicted by the best French painters of the time, including Pierre Mignard (1612–1695), François de Troy (1645–1730) and Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659–1743). Depictions of James III were engraved by artists such as Jacqueline de Boissière and copied for miniature lockets by artists including Anne Chéron (c.1633–1718).

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Prince James Francis Edward Stuart (1688–1766), Son of James VII and II 1701

François de Troy (1645–1730)

National Galleries of ScotlandAfter a failed Jacobite invasion with French support in 1708, Louis XIV eventually halted his direct support to the Stuarts in line with the terms of the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. James III/VIII and his court therefore found a welcoming host in Duke Leopold of Lorraine (1679–1729).

The death in 1714 of Queen Anne (1665–1714), who became Queen following the death of William III in 1702, prompted the Jacobites to prepare for rebellion. John Erskine, Earl of Mar (1675–1732) raised the Jacobite standard at Braemar on 27th August 1715. Although the victory at the Battle of Sheriffmuir was claimed by both sides on 13th November, the Jacobites lost the battle of Preston the following day – before James III could arrive from Lorraine.

Image credit: Government Art Collection

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) (studio of)

Government Art CollectionSupport for the 1715 uprising – known as 'The '15' – was galvanised by Scottish resentment regarding the 1707 Act of Union, which effectively joined England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain. Likewise, men such as George Keith, 10th Earl Marischal (1693–1729), who commanded a small fleet of Spanish marines, used this antipathy to prepare another uprising in 1719. This abortive Spanish Jacobite expedition to Scotland failed and led George Keith to exile in Spain and Prussia.

From then on, the Jacobite movement went underground but miniature portraits were still circulating in the Jacobite community, while adherents to the movement toasted to 'The King Over the Water'. After a short stay in Avignon (1716–1717), Pesaro during the spring of 1717, and Urbino for most of 1718, the Jacobite court in exile reached Rome in November 1718.

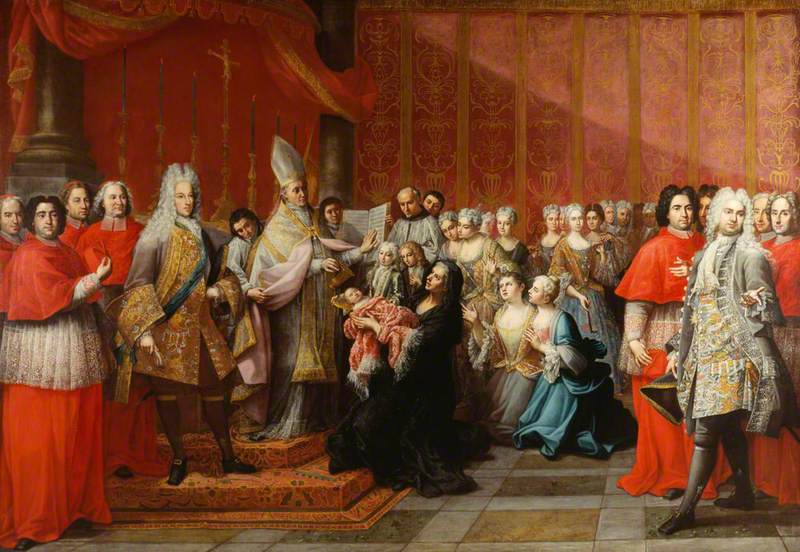

On 31st December 1720, the wife of James III/VIII, Maria Clementina Sobieska (1702–1735), gave birth to Charles Edward Stuart – Bonnie Prince Charlie – in Rome. James III/VIII commissioned a monumental painting in 1725, the year Bonnie Prince Charlie was rebaptised by Pope Benedict XIII (1649–1730) and the year his second son, Henry Benedict Stuart, Cardinal-duke of York (1725–1807) was born.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

The Baptism of Prince Charles Edward Stuart 1725

Antonio David (1698–1750)

National Galleries of ScotlandLike in France, the Stuarts in Italy continued commissioning works of art to assert their claims. Since the 1730s, the court in exile had been employing Italian and Swiss painters such as Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757) and Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789) to produce a continuous flow of images intended for their supporters.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720–1788), Eldest Son of Prince James Francis Edward Stuart 1737

Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789) (after)

National Galleries of ScotlandBut the Jacobites also commissioned painters from English and Scottish families loyal to their cause. For instance, the Scottish painter Cosmo Alexander (1724–1772), who painted the below portrait of Bonnie Prince Charlie, was the son of John Alexander (1686–1766) who had painted the 1st Viscount Dundee in 1732 (pictured above).

Image credit: The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum

Charles Edward Stuart (1720–1788) 1750–1751

Cosmo Alexander (1724–1772)

The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & MuseumIn 1745, the Jacobites rebelled again, and their army reached as far south as Derby, before retreating to Scotland. The Jacobite forces were eventually slaughtered in 45 minutes on Culloden Moor. The defeat at Culloden effectively signalled the end of military actions on British soil. However, Jacobitism as a political force did not end at Culloden, and Bonnie Prince Charlie eventually returned to Rome.

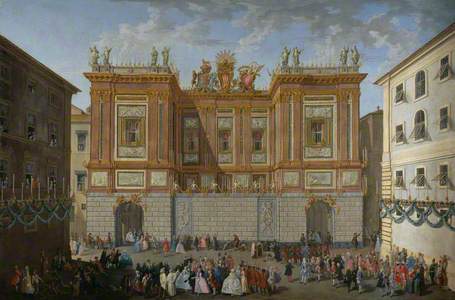

Until 1747, all of Bonnie Prince Charlie's children had died in infancy and his father wanted an artwork displaying the continuity of Jacobite pretence. As such, James III/VIII commissioned another monumental painting, this time depicting him welcoming his second son, Prince Henry Stuart, in front of the Palazzo Del Re, the exiled Stuart Court residence in Rome.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Prince James Receiving his Son, Prince Henry, in Front of the Palazzo del Re c.1747–1748

Paolo Monaldi (1720–1799) and Pubalacci and Louis de Silvestre (1675–1760)

National Galleries of ScotlandUpon James III/VIII's death in 1766, the Jacobites recognised Bonnie Prince Charlie as Charles III, but no European power was willing to do the same. Although politico-military Jacobitism died with Bonnie Prince Charlie in 1788, the Jacobite court was to stay in 'Perpetual Pretence' until the death of Henry Stuart in 1807.

Image credit: Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection (Dundee City Council)

'Lochaber No More', Prince Charlie Leaving Scotland 1863

John Blake MacDonald (1829–1901)

Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection (Dundee City Council)The Jacobites continued to produce works of art asserting their rights, and their story would later be claimed by the numerous nineteenth-century artists who heavily contributed to the romanticisation of Jacobitism.

Jérémy Filet, cultural historian specialising in Jacobitism

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Stefano Baccalo, and Calum E. Cunningham, 'The Stuarts in Italy, 1766–1807: A Court in Perpetual Pretence' in The Court Historian 29.2, 2024

Edward Corp, The King Over the Water: Portraits of the Stuarts in Exile after 1689, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 2001

Edward Corp, A Court in Exile: The Stuarts in France, 1689–1718, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Edward Corp, The Stuarts in Italy, 1719–1766: A Royal Court in Permanent Exile, Cambridge University Press, 2014

Jérémy Filet, 'You're Dead to Me: The Jacobites', BBC Radio 4, 2023

David Forsyth (ed.), Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites, National Museums Scotland, 2017

Daniel Szechi, 1715: The Great Jacobite Rebellion, Yale University Press, 2006

Daniel Szechi, The Jacobites: Britain and Europe 1688–1788, Manchester University Press, 2019

The Stuarts & The Stuarts in Exile. The story of the greatest & longest-ruling dynasty, BBC documentary presented by Dr Clare Jackson, 2018