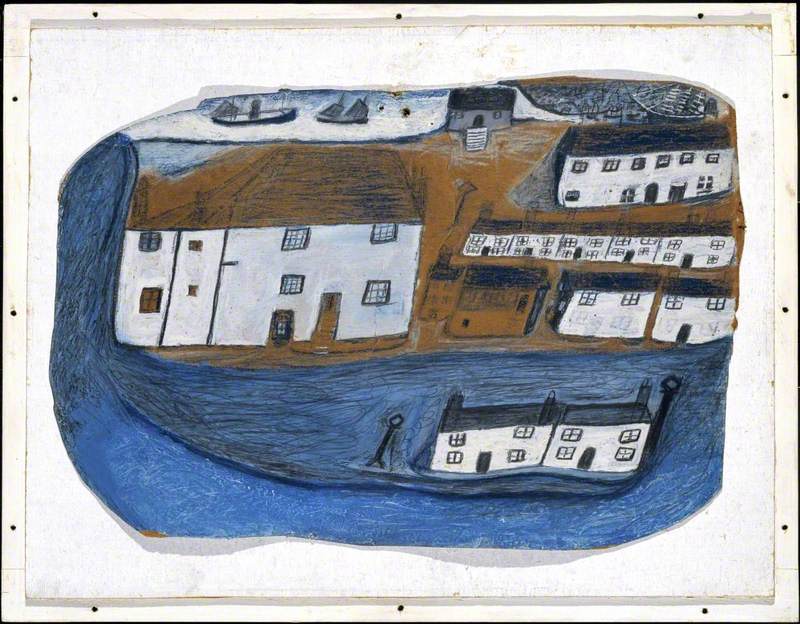

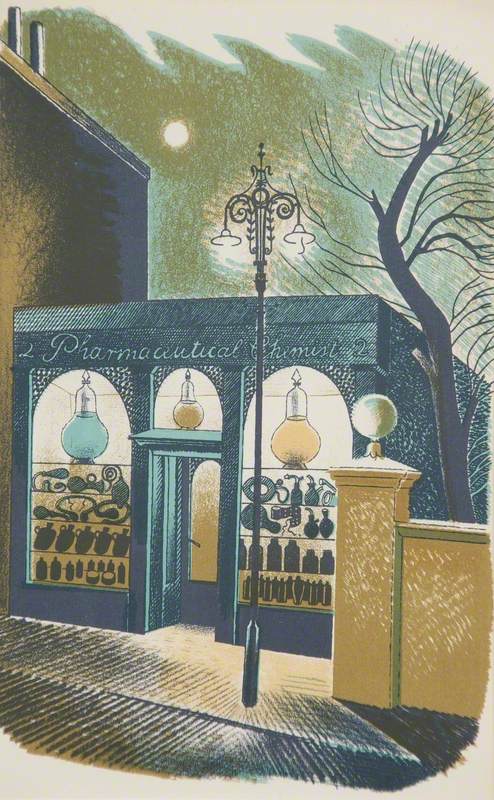

It's so easy to read a picture wrong. Looking at this one, walking round the newly opened Kettle's Yard recently, I thought I had a story that fitted neatly.

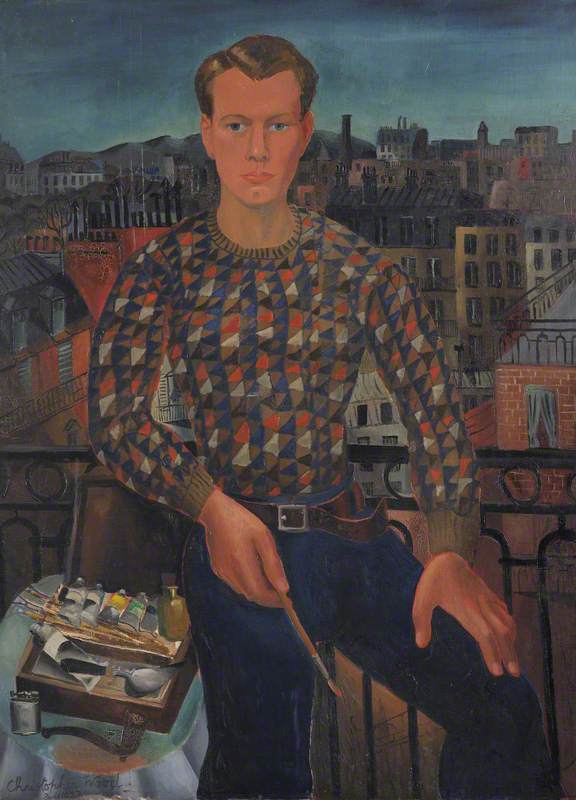

This, I assumed, was a painting that captured an existential envy, a painting in which Christopher Wood, public-school educated and art-school trained, reaches out for the artlessness he so admired in the paintings of Alfred Wallis, the St Ives fisherman-painter discovered by Wood and his friend Ben Nicholson in 1928. Reaches out for and misses, since he just can't quite suppress what Wallis so effortlessly excludes from his pictures: perspective and scale and academic technique.

Yes, those sailing boats recall Wallis's – almost always viewed side on and pasted to the sea like plaques – but they aren't pictograms of boats. You can see the curve in those white sails, sense the curl of the wake from the hull in the foreground. And in this reading of the picture its melancholy doesn't just derive from the fact that it was made shortly before Wood died by suicide in 1930 – though that knowledge casts an inevitable shadow over the scuffed grey sea – but because of the sense that its maker can't escape his own artistic self-consciousness.

There's no question that Wood hugely admired Wallis. In November of 1928, in a letter to Ben Nicholson's wife Winifred, he confessed to the growing effect Wallis's art had had on him: 'more and more influence de Wallis not a bad master though'. The Franglais of 'de Wallis' is a knowing joke, given how robustly detached Wallis was from any fine art tradition. He once had to be persuaded by Nicholson that it was not a good idea to fix paintings to the wall by hammering a nail through the centre of the image. But later the same month Wood went even further, 'I am not surprised that no one likes Wallis, no one liked Van Gogh for a long time did they?' That seems, to me, to be pushing it, though there's no reason to doubt Wood's sincerity in making the comparison.

But what I'd read at first glance as a losing battle to get beyond academic technique – a little fable about early Modernism's infatuation with the primitive – may not be anything of the kind. Perhaps that first story isn't neat but trite. In July of 1930, just a month before his death, Wood wrote to Winifred in much more upbeat terms about his work. It had become, he said, 'more direct in idea and less naive'. So maybe Le phare achieves exactly what Wood wanted in the way it sits between primitivism and something else – the theatricality of some details and the isolated vivacity of others.

And what about that patch of light on the ocean towards which the boat in the background is sailing, its bow lifting upwards? That calls to mind another phrase from Wood's letters, one in which he expressed his admiration for Winifred's resilience after she and her husband had been through a difficult time: 'You come out of it', wrote Wood, 'like a sailing boat without any water in its sails gleaming white in the sun and bang on the crest of a wave'. Is it a despairing picture this or a hopeful one? I can't be sure anymore, and I like it much more for that.

Tom Sutcliffe, Arts Broadcaster, BBC Radio 4