This Curation centres around the three 1869 portraits of black men painted by Thomas Stuart Smith, the founder of The Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum in Scotland. As a culmination of an internship project with the Stirling Smith, this curation explores the paintings in light of black portraiture in the Victorian era and in the Stirling area.

Thomas Stuart Smith

Thomas Stuart Smith was born in Scotland in late 1815, and travelled around Europe painting and learning from others. After the death of his father in ca. 1835, Smith made contact with his uncle Alexander Smith (a banker), who funded Thomas’ painting exploits around Europe. Smith’s father was involved in the colonisation of Canada as a secretary and accountant of the Canada Company, and was later active as a merchant in Cuba. Thomas lost his father’s letters, and so we are uncertain of what this merchanting involved, but sugarcane was the most prominent Cuban product at the time — grown by thousands of enslaved people. Despite no direct links to slavery, it is important to note that Thomas Stuart Smith likely benefitted from it.

Alfred Wilson Cox (1820–1890)

Oil on canvas

H 75 x W 62.1 cm

The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum

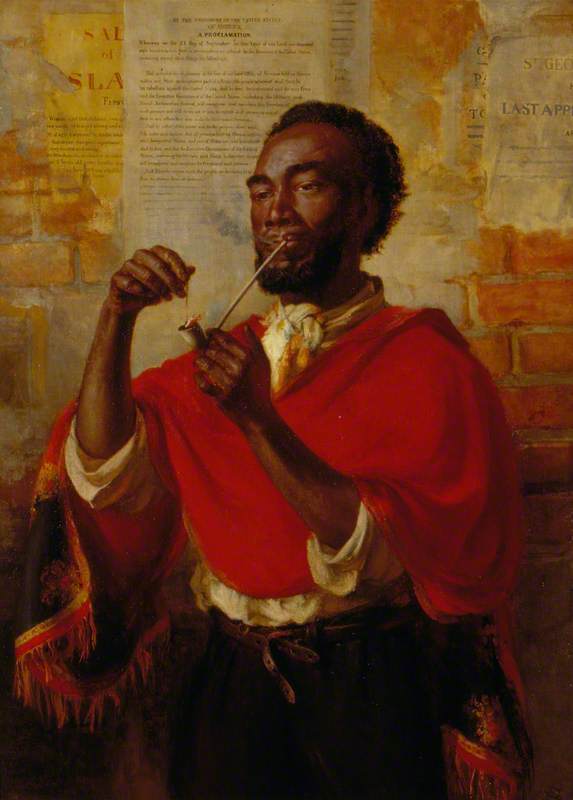

The Pipe of Freedom

In this portrait, Smith celebrates American abolition of slavery with the inclusion of the Emancipation Proclamation in the background. The textual element of the proclamation turns the static portrait into a narrative, implicating it within the American Civil War but also within the greater narrative of civil rights even up to the present day. The pipe in the painting contains the very tobacco that enslaved peoples worked to produce, so the act of lighting the pipe creates a great symbol of ignition and rebellion. Smith submitted this painting to the Royal Academy for its summer exhibition but was rejected, on what he thought were political grounds, and instead hung the painting in a Select Supplementary Exhibition in Old Bond Street.

Thomas Stuart Smith (1813/1814–1869)

Oil on canvas

H 106.8 x W 78.7 cm

The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum

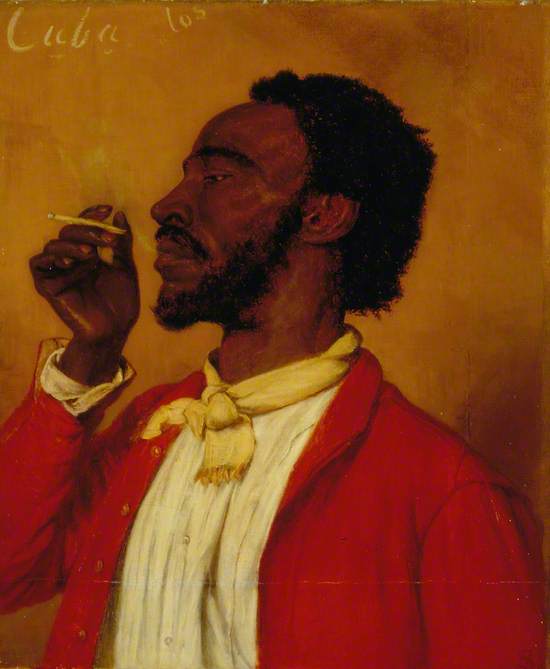

A Cuban Cigarette

In this portrait, the model smokes an already-lit cigarette, dressed in clothes of a higher class, perhaps denoting that this is supposed to be after the moment of freedom of the enslaved peoples. The ‘Cuba’ lettering could be a link to Smith’s father’s merchanting exploits in Cuba, or it could also be an allusion to the slavery that still continued to boom in Cuba in these years. Smith seems to focus on the individuality of the man in this portrait: there is a greater detail here of the fold in his shirt, the creases of the jacket, and the exact shadows of the bones of his face. This portrait is celebratory in a similar way to The Pipe of Freedom, attending not so much to the struggles of this man or his people, but their success.

Thomas Stuart Smith (1813/1814–1869)

Oil on canvas

H 67 x W 56 cm

The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum

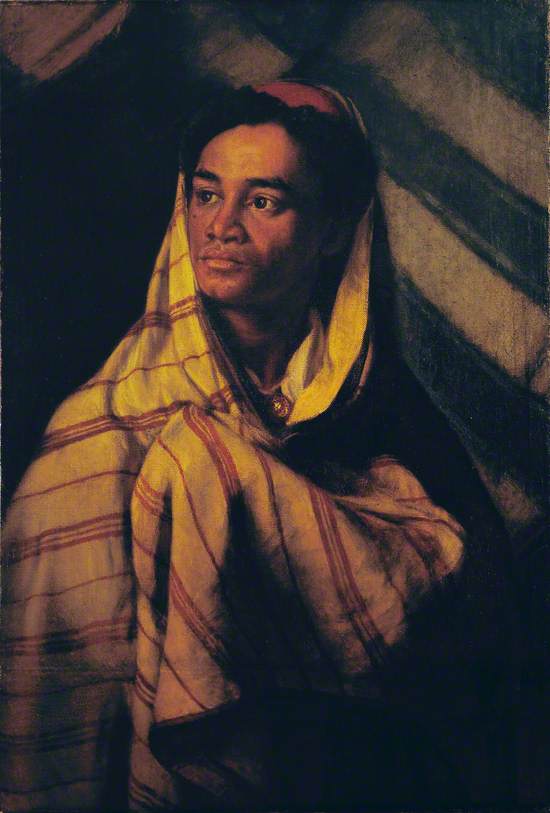

A Fellah of Kinneh

This portrait, hung in the 1869 RA Summer Exhibition, presents an ordinary man from North Africa (Jan Marsh notes that ‘Kinneh’ likely denotes Qena, a town north of Luxor). Implications of slavery and abolition are less obvious in this painting, which rather focuses on the life of ordinary people. The blanket is Moroccan in design and the background appears to be a nomad’s tent. Smith was hugely interested in travel and culture, but also lived in a time where the colonial gaze was the norm. The colonial gaze was developed as an idea by Frantz Fanon in which the coloniser and their ‘gaze’ create Otherness in the colonial subject, something that is evident in this painting. Egypt would indeed soon be occupied by British forces in 1882.

Thomas Stuart Smith (1813/1814–1869)

Oil on canvas

H 96 x W 66 cm

The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum

Black Portraiture in the Victorian Era

Although Victorian art is often seen as a period of ‘white’ art, the black presence is larger than first assumed. However, Jan Marsh notes that black presence was ‘less than it should be’ in light of the benefits Britain (and its booming art market) gained from the traffic of Caribbean and African people and goods, ‘so it can be said that Victorian art owes its existence to those who are relatively absent from its images.’ Black presence in Victorian art was often visually marginal, presented as exotic and ‘Othered’ servants. The other common trope in this era was of white self-congratulation, such as in Barker’s The Secret of England’s Greatness, where Victoria presents a Bible to an African man in a self-congratulatory gesture.

Smith's Black Portraiture

Smith’s portraiture represents somewhat of a break from Victorian tropes, in positioning the ex-enslaved person as the noble subject who lights his own pipe. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the timeline of black presence in art was not linear during this period: Douglas Lorimer notes that ‘as the century advanced, [black people] increasingly encountered racial intolerance.’ Smith’s abolitionist paintings must thus not be viewed as a concrete turning point in the depiction of black people — and this leads further to a conclusion that American abolition itself was not the universally emancipatory moment that we like to think of it as, because African Americans still experienced immeasurable suffering afterwards.

Stirling and American Abolition

As a smaller city of under 20,000 people in the centre of Victorian Scotland, one might imagine Stirling to have little involvement in the huge political issue of American abolition. However, GALE Archive records of the Stirling Observer show numerous amounts of lectures on the American situation. These took place mostly in churches (including Free North Church, and Erskine U.P. Church) and the School of Arts in Stirling. The nuanced political circumstances were widely discussed, but abolition as a moral (and Christian) issue was also attended to. It is likely that Smith was aware of these discussions, as he often attended lectures and talks in his locality.

Where now?

As contemporary viewers of Victorian Black Portraiture, we are not exempt from the narrative of civil rights and anti-racism. A long-overdue and fought-for upheaval has taken place in the past year, in which universities, museums and the art world at large have reckoned with their histories of slavery, colonialism and racism. Scotland too has taken part in recent Black Lives Matter movements, whether that be in the 2020 protests or in art projects such as Wezi Mhura’s Scottish BLM Mural Trail. The history of slavery and colonialism still have ramifications in our contemporary world, and so it is essential to examine the art in our museums and wider society in order to include black people, voices, and works.