This exhibition explores why adults became particularly interested in portraying children from the nineteenth century onwards. Artists constructed the children they wanted to see, especially as they were personally involved with religion and education. These artworks show how they projected their ideologies and anxieties for the future onto their young sitters.

We are grateful to Third Year History of Art students at Oxford Brookes University for creating this exhibition as part of their 'Curatorial Practice' module.

Evelyn Mary Dunbar (1906–1960)

Oil on panel

H 77.5 x W 130 cm

Oxford Brookes University Special Collections and Archives

Natural Innocence & White Saviour Complex

The concept of innocence started to become prevalent in eighteenth-century children’s portraiture, which focused on the pure eyes of the sitters, as well as on their intrinsic relationship with nature, often underlined by their integration into a landscape. The mass reproduction of these images, through copies and prints present in households, ensured the persistence of a romantic vision of childhood for several upcoming generations of artists and educators. This ideal found an echo in religious educators, who saw children as pure souls to be guided along the right path.

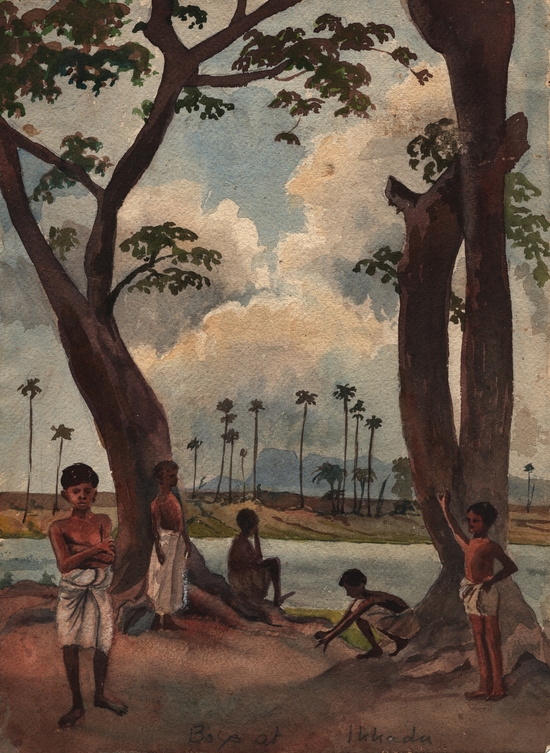

Boys at Ikkada

Agatha Hellier observes a group of boys passively integrated within nature before their impending induction into the westernised education system. As a Methodist missionary teaching in South India, the artist projects her religious vision of preserved childhood innocence and impressionability. The composition creates voyeuristic otherness through distance between the figures and picture plane. When related to The Pathfinder, these boys symbolise the starting point: lost before Jesus’s guidance towards civilised adulthood.

Agatha Gay Hellier (1897–1980)

Watercolour on paper

H 39 x W 29 cm

The Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History

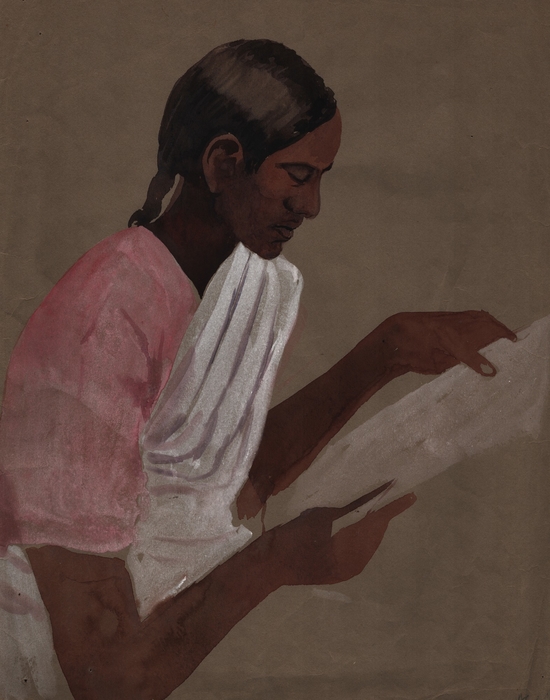

Portrait of a Young Boy

This ideal student, concentrating on his reading in a neat outfit, was probably taught by the artist while she acted as a missionary educator from 1923 to 1951. The rough sketch suggests a documentation of her work’s reality. However, as a white woman in a colonialist context, she presents a submissive vision of the child, likely converted, which contrasts with the playful and active relationship to reading depicted by Dunbar.

Agatha Gay Hellier (1897–1980)

Pencil on paper

The Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History

Endangered Youth and Reinventing the Child

When James Smetham (1821–1889), decided to paint Hugh Miller, he was teaching at Westminster College. His vision of a romantic childhood, however, demonstrates a darker shift toward adulthood. He projected his own anxieties about the future onto his youthful symbol threatened by the world, a theme dear to nineteenth-century artists. Indeed, the age of urbanisation also marks an era of concern for children, victimised by poverty-ridden cities. Artists followed the lead of social workers, who worried about a deterioration of society. Some focused on public schools and the study of children's development, while others took a more patriotic approach, wishing to produce individuals who were fit for their country.

Hugh Miller Watching for His Father's Vessel

A polymath from a poor background, Hugh Miller embodied the benefits of knowledge, a possible reason why the artist, who was also a teacher, chose to depict him. This scene, inspired by the quote from Miller's biography present on the frame, shows him grieving for his father. The artist chose a colour palette that blends the child in the seascape, highlighting his romantic ideal of innocence to be protected and guided.

James Smetham (1821–1889)

Watercolour on paper

H 40 x W 70 cm

The Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History

This desire for societal improvement led to the creation of organisations such as the Scouts, who used art to promote their ideology. Lord Baden Powell, founder of The Boy Scouts Association, praised the painting The Pathfinder, by Ernest Stafford Carlos (1883-1917), as providing “an immense amount of good among boys”. Used as a role model, it was distributed throughout the British Empire in numerous copies, participating in a standardisation of children.

The Pathfinder

The young sitter is portrayed like an adult, showing poise and responsibility, in stark contrast with the other artworks exhibited. Indeed, the Scout organisation aimed at shaping capable citizens. The presence of Jesus reminds that religion was perceived as a moral compass in the twentieth-century world in crisis. This copy of a painting by Ernest Stafford Carlos testifies to the influential imagery of the original work, created to promote Scouting.

Ernest Stafford Carlos (1883–1917)

Oil on canvas

H 116 x W 83 cm

The Scouts Heritage Service

Children as Vessels: Carrying Hope for a Secure Future

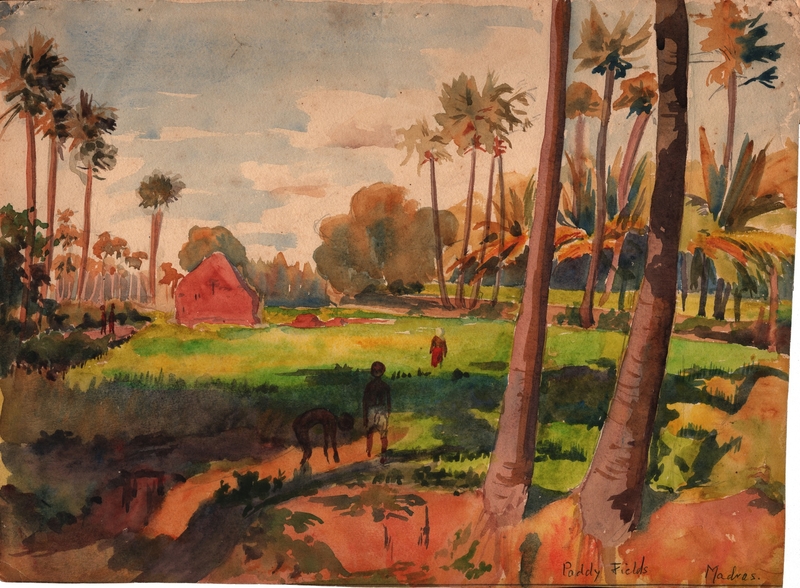

The devastating impact of the Second World War compelled the opening of emergency teacher training colleges across Britain, including Bletchley Park where Evelyn Dunbar (1906-1969) was an artist-in-residence. Here, Dunbar planned a mural to encourage and inspire new educators. Although the mural was never executed due to the artist’s poor health, her sketches provide valuable insight into representations of education at this time as an engaging, inclusive practice indispensable in the prevention of further disaster.

Through her work for the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, Dunbar understood both the societal damage inflicted by the war and the need for positive propaganda. As a key figure in the documentation of women’s work during the war, she knew that they had a crucial role in rebuilding the country, including the enlightenment of future generations. Contrary to Hellier, who, although she taught young women at Royappehta Girls’ High School, focused her missionary watercolours on boys, Dunbar imagined both boys and girls playing and learning cohesively.

Preliminary Sketch

Evelyn Dunbar’s sketch was intended for a mural for Bletchley Park Teacher Training College, opened due to new demand for educators after the losses of the Second World War. Compared to the passivity of Boys at Ikkada, these children actively engage with the natural environment, playful and eager to learn. Dunbar projects a hopeful image of an inclusive future society shaped by both young girls and boys, enhanced by the vibrant primary colours and childlike medium.

Evelyn Mary Dunbar (1906–1960)

Oil & watercolour on paper

H 19 x W 29 cm

Oxford Brookes University Special Collections and Archives

An Art Collection linked to Education

These artworks cement the relationship between their historical provenance and the current curriculum of Oxford Brookes University. Oxford's role as the 'Birthplace of Methodism' also means that it is ideally suited to host the Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History, as well as Hellier's watercolours. Bletchley Park College (for which Dunbar made her sketches) moved to Wheatley in the 1960s, whilst Smetham's collection joined Westminster College in the 1990s.

If you explore the campus, you will find a copy of a sculpture by John F. Matthews (1920-1995), with the figure of Jesus towering over a child, along with a quote from the Bible “Train up a child in the way he should go”, that directly echoes 'The Pathfinder'.

Future graduates in Education and Teacher Training pass these on their way to classes on the Harcourt Hill Campus, where they participate and explore ideas of childhood and education that have evolved since the creation of these items.

How do you think your education, and the traditional images of childhood, affected your transition to adulthood?