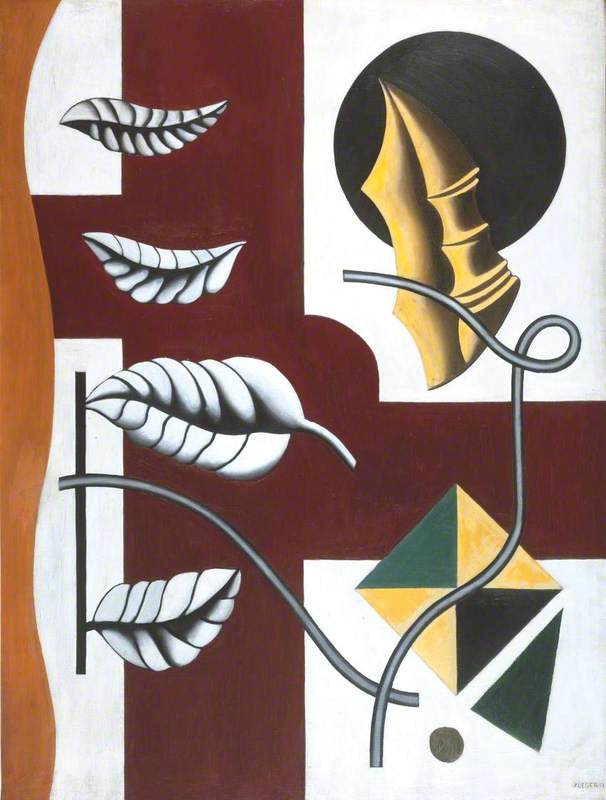

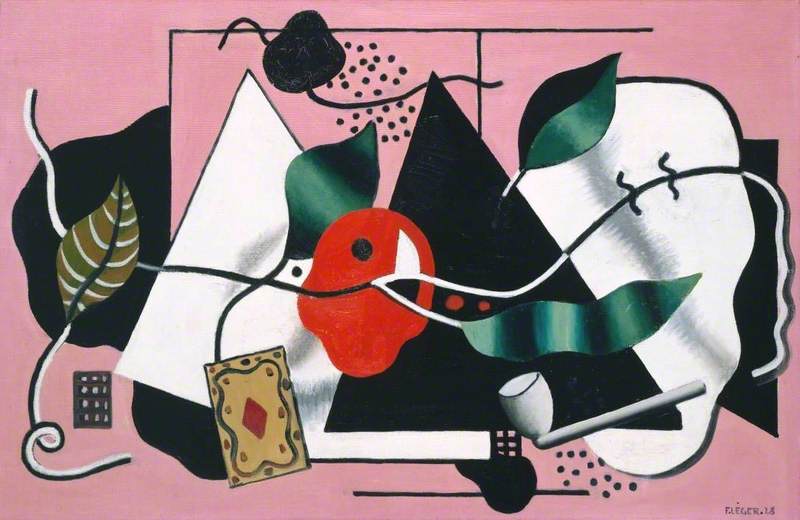

(b Argentan, Normandy, 4 Feb. 1881; d Gif-sur-Yvette, Seine-et-Oise, 17 Aug. 1955). French painter and designer. After passing through various early influences he turned to Cubism in 1909. Although he is regarded as one of the major figures of the movement, he always stood somewhat apart from its central course: he disjointed forms but did not fragment them in the manner of Braque and Picasso, preferring bold tubular shapes (he was for a time known as a ‘tubist’). During the First World War he served as a sapper in the front line, then as a stretcher-bearer, and his experiences were ‘a complete revelation to me as a man and a painter’. They enlarged his outlook by bringing him into contact with people from different social classes and walks of life and also by underlining his feeling for the beauty of machinery.

Read more

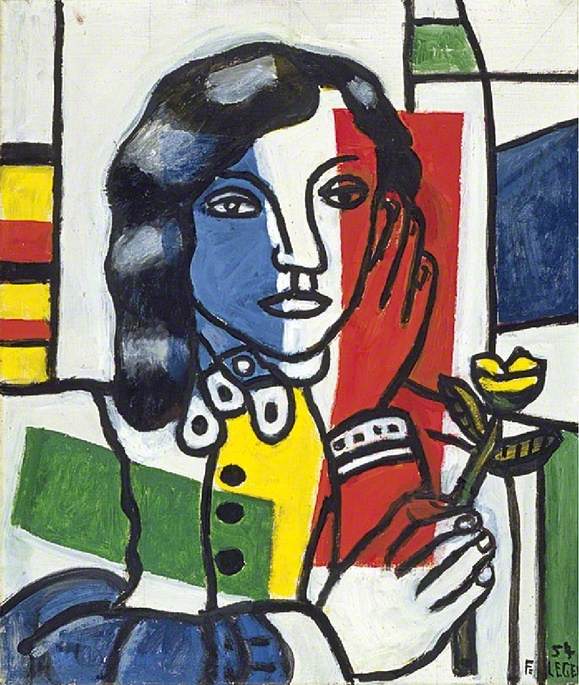

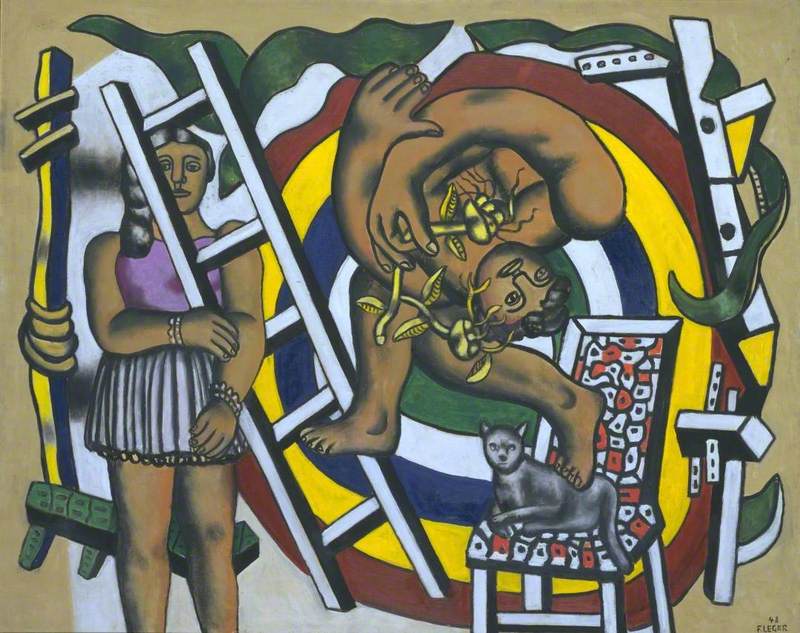

Henceforward he made it his ambition to create an art that would be accessible to all ranks of modern society. After being gassed, he spent more than a year in hospital and was discharged in 1917. During the next few years, his work showed a fascination with machine-like forms, and even his human figures were depicted as almost robot-like beings (The City, 1919, Philadelphia Mus. of Art). In 1920 he met Le Corbusier and Ozenfant, who shared his interest in a machine aesthetic, and in the mid-1920s his work became flatter and more stylized, in line with their Purist style. He used bold, poster-like contrasts of form and colour, with strong black outlines and extensive areas of flat, uniform colour. In the interwar years he expanded his range beyond easel painting with murals (sometimes completely abstract) and designs for the theatre and cinema. He was also busy as a teacher and travelled extensively, making three visits to the USA in the 1930s. The contacts that he made during these visits stood him in good stead when he lived in America during the Second World War.Léger's work of the war years included pictures of acrobats, cyclists, and musicians, and after his return to France in 1945 he concentrated on the human figure rather than the machine. He joined the French Communist Party soon after his return and favoured proletarian subjects. Some of his pictures in this vein are very big, notably The Great Parade (1954, Guggenheim Mus., New York), and in his later career he also worked a good deal on large decorative commissions, including stained-glass windows and tapestries for the church at Audincourt (1951) and a glass mosaic for the University of Caracas (1954). Many honours came to him late in life, notably the Grand Prix at the 1955 São Paulo Bienal. Shortly before his death he bought a large house at Biot, a village between Cannes and Nice, and his widow built a museum of his work here, opened in 1960. In the catalogue of the exhibition ‘Léger and Purist Paris’ (Tate Gallery, London, 1970), John Golding wrote of Léger: ‘No other major twentieth-century artist was to react to, and to reflect, such a wide range of artistic currents and movements. Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Purism, Neo-Plasticism, Surrealism, Neoclassicism, Social Realism, his art experienced them all. And yet he was to remain supremely independent as an artistic personality.’ However, despite Léger's centrality in modern art, Edward Lucie-Smith thinks that he ‘still ranks as an under-appreciated artist, one who is on the whole more respected than loved. His work has a deliberate harshness which repels many spectators’ (Lives of the Great Twentieth Century Artists, 1986). Certainly he never achieved the popularity with ordinary working-class people that he aimed for.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)