Montague John Rendall (1862–1950) c.1938

Elizaveta Petrovna Cheremisinova (Elisabeth Tcheremissinof) (1877–1963)

Winchester College

Elizaveta Petrovna Cheremisinova (also known as Elisabeth Tcheremissinof) was a Russian sculptor, portrait medallist, and a more occasional painter of portraits and other subjects, but this was a redirection from first being a skilled artist in decorative leatherwork, including bookbinding. Of aristocratic paternal descent back to the 17th century, she was born in St Petersburg and in the 1939 UK Register gave her birth date as 9th November 1879, though this has been corrected to 9th February by another hand. The year also appears elsewhere as 1874 but it is more likely that she was born on 9th February 1877: her Russian Orthodox baptism is recorded in the church of the Peterhof Palace on 13th March of that year. Given the likely proximity of her birth and baptism, it is possible she was in fact born in a family house in Peterhof – 20 km outside the city – and she completed her early education at the Smolny Institute for Noble Maidens, the leading St Petersburg school for aristocratic girls, in 1895 (when she would have been 18, rather than 21 if born in 1874).

Elizaveta's mother was Anna Vasilievna Trewheller (variably Truveller/Trewheeler or Trewhella/ar, 1842–1908), Pyotr’s first wife. Her maternal great-grandfather, John Trewheller, was from Penryn in Cornwall, and had worked as a wheelwright in the Arsenal at Woolwich and in the naval dockyards of the Medway. Her grandfather, born at Gillingham, Kent, on 24th June 1808, was baptised Frederick William Trewheller there on 17th July. He trained as a civil engineer in Russia, settled in St Petersburg from 1833 and built bridges for the Russian railways as head of the corps of railways. He was naturalised as Vasily Ivanovich Truveller in 1856 and designed the sluices for the paper mill, the military schools camp and much of the layout of Peterhof. He is also credited in the memoir of his granddaughter, Martha von Rosen (daughter of Elizaveta’s immediately elder sister Anna) with the design of ‘some of the beautiful buildings and fountains’ of the town, where he enjoyed Imperial favour. The house he built for himself, at 46 St Petersburg Avenue and now part of a hotel, is still called ‘Truveller’s House’. He died aged 51 in 1859.

After leaving school Elizaveta travelled to, among other places, Egypt, Jerusalem, Italy, France and Switzerland. Her early work in leather is first evident in the winter of 1903/1904, when examples were exhibited at the Österreichischen Museum für Kunst und Industrie in Vienna and she was praised in the museum’s magazine for July 1904 as a ‘strong, well-educated talent’. Eight leather items by her, mainly decorated bindings, were also shown at the St Louis Universal Exhibition of 1904. Also shown were photographs of her leather binding of a volume of Heine’s poetry, purchased earlier in the year in St Petersburg by the Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia (1847–1928).

By 1905/1906, however, she had turned to sculpture. She first studied it for three years in Vienna, then two in Paris and before 1911/1912 also reportedly spent a year in Germany, though when is not clear. Leonard Forrer’s Biographical Dictionary of Medallists (1916: vol. 6, p.44) names her as ‘Vera Elizabeth’ and her teachers as ‘Strasser, Gauquié, and Roland’ – that is, Arthur Strasser (1854–1927), Henri Désiré Gauquié (1858–1927) and perhaps Roland Mathieu-Meusnier (1824–1896). The first was born in what is now Slovenia and worked mainly in Vienna. The second was French, working in Paris, but being taught by Mathieu-Meusnier, also French, would imply she was either there before 1896 or that he had taught elsewhere, so ‘Roland’ may be someone else.

An Italian-printed Russian book, Nikolai and Alexandra: court of the last Russian emperors, 1890–1917 (Slavia-Interbook, 1994) includes a short entry on Cheremisinova, saying she ‘Completed a full course of study in the workshop of Professor Strasse [sic] in Vienna, then worked at the Académie Colarossi in Paris’: this is repeated in M. B. Piotrovskii’s Russian Art in the Hermitage: famous and forgotten masters of the 19th and first quarter of the 20th century (Slavia, 2007). She exhibited three sculptural works at the 1909 Paris Salon, sent in from 4 Rue Huygens; a portrait of Lady Mary van Haast (no. 3857) and 'Three heads of children’ (no. 3858) which the Journal des Artistes (25th July) complimented and confirmed was a single marble. Forrer also notes her showing a portrait medallion of the psychiatrist Prof. Dr Robert Gaup there (medallions not being in the main catalogue). By 1910 she was back in Vienna, since listed to 1912 as a member of the Society of Women Artists in Austria (Vereinigung bildender Künstlerinnen Österreichs, est. 1910), with her studio at 22 Marokkanergasse.

A brief article (including a portrait photo) appeared in the Vienna magazine Sport und Salon of 1st April 1911, calling her ‘Veta v[on] Tcheremissinoff’: it says she had only been doing sculpture for five years, was then working on a statuette of the Russian ambassador’s wife and was planning a studio display of her work. The Studio magazine for 1911 (vol. 10, ‘Studio Talk’, and its international edition) also mentioned her in relation to her entries in that year’s second exhibition of the Society of Women Artists as ‘Neta Tcheremissinof, a young Russian sculptor residing in Vienna, [who] shows a tight grip of her subject, energy to carry out her artistic intentions, and true workmanship.’ She reportedly received various commissions and may have formed an early connection with the aristocratic Kinsky family, who had links there and in Prague: in 1937 she exhibited a portrait in tempera of Count P. Kinsky at the Royal Academy in London.

Despite this Vienna presence, her ongoing connection to the family home in St Petersburg is supported by her involvement as a listed member of the Russian Art Industrial Society (1904–1917). In 1911/1912, hers was one of 31 proposals submitted for a monument to the Empress Maria Feodorovna in St Petersburg. Following her return from Austria or Germany she modelled it in studio space provided on the fourth floor of the residence of Count Ichiro Motono (1862–1918), Japanese ambassador to Russia 1906–1916, who had become a close friend of her father. Motono later stated in a Japanese newspaper interview that he made the space available because hers was a late entry for the competition, for which she had returned to St Petersburg without having time to find a studio. She then continued doing other work there including a bronzed plaster statuette of Motono himself in Western hunting dress, a now-unlocated bust of him that was exhibited in St Petersburg in 1916, and one of the visiting Japanese flute (shakuhachi) virtuoso Tozan Nakao (1876–1948). The Tozan Nakao Foundation in Kyoto has her finished bust of him and a photo of her modelling an early version at a sitting with Nakao, taken in the residence by Motono himself on 3rd October 1915. In 1917, Motono recalled her manner of working as ‘very enthusiastic and she finishes very fast.’

Though not formal prize-winner for the Maria Feodorovna statue, her proposal was the one progressed, so the Empress may have been consulted, recalled her book purchase of 1904 and expressed a preference. A Russian source says she completed a life-size clay in May 1914 but three surviving photos in the Hermitage collection appear to be of the half-scale one, and the scheme foundered with the outbreak of the First World War. She also began another project in 1914, when the Society of St Olga in the city of Pskov asked her to make a memorial to its patron saint, though (oddly) calling her ‘architect’ rather than sculptor. This was approved by the city council in August, as the war began and killed it off as well. The Hermitage holds two versions of her small bust of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, dated 1915, a bronze and a plaster on an integral drum plinth: both were presumably done at the same time. A Russian student-file reference also notes her presence at the ‘Psycho-Neurological Institute’ in St Petersburg in 1915 but does not say why, though Motono (so far the only source) reported that her father died in that year, which presumably caused family distress and disruption.

In November 1916 Motono was appointed Japanese Foreign minister and appears to have encouraged Cheremisinova in following him to work in Tokyo. The Japanese MP Seiki Kuroda (1866–1924) – himself a noted painter – was also a sponsor of her visit. She had arrived by early January 1917, staying at the old Imperial Hotel and initially using a service space it provided as a studio but, by June, had rented one at Uchisaiwai-Cho 1–4. Frank Lloyd Wright, who also had working room in the old hotel while he built the new Imperial (1917–1923) briefly mentions her in his autobiography as ‘Princess Tcheremissinoff’ and one of the ‘talented’ and ‘charming Russians’ he met in Japan, their presence no doubt swelled by the Revolutions of 1917.

She was the only European artist selected for the second and third Bunten art exhibitions (mounted by the Ministry of Education) in Ueno, Tokyo, in October 1917 and 1918, each attended by around a quarter of a million visitors in the five weeks they were on. In 1917 she showed her statuette of Motono and in 1918 a bust of Hachirojiro Mitsui (1849–1919), head of the Mitsui corporation: both were said to be bronze but may only have been bronzed plasters. Motono’s family still had his version of the bronzed plaster statuette in 1984, in damaged condition.

Cheremisinova's Japanese circle also included the Belgian-trained sculptor Kozaburo Takeishi (1877–1963) to whose studio in Komagome, Tokyo, she was a frequent visitor. A photograph of her with him there includes a younger European woman of family resemblance who may be her brother Vladimir’s daughter, Ekaterina (b.1890), a European linguist who spent much time teaching in the East. This included visiting Japan, from where she left for Australia in mid-1919: she eventually married in France to an émigré Russian called M. Arapov in October 1931. Another group photograph, including Count Motono and his wife, shows Cheremisinova and her married elder sister, Anna Petrovna Kügelgen (1875–1966), with an unidentified European couple of whom the lady is also of older family resemblance. The image is thought to have been taken in Tokyo but three others in the group were taken in Russia, so it may be in the Japanese embassy grounds in St Petersburg (with two uniformed Japanese on the right).

Seiki Kuroda’s diary shows that at least one of Cheremisinova’s two married elder sisters (Maria, b.1865, or Anna, b.1875) was with her in Tokyo in spring and summer of 1917 but which and for how long is unclear, or if they arrived together. Anna’s residence in Estonia and the fact that their niece, Ekaterina Vladimirovna, never returned to Russia suggests family dispersal from there as a result of the 1917 Revolutions.

Unfortunately, Cheremisinova’s prime Japanese supporter, Count Motono, died in September 1918, shortly before her second Bunten appearance but she remained in Tokyo for several more years. In late February 1919 and just before his death on 4th March, she went to see Jinzo Naruse (b. 1858), Christian founder of the Japanese Women’s University, whom she may also have met during his earlier travels in Europe. She then rapidly made a small relief portrait of him that was replicated in numbered plaster copies for graduates and others connected with the University. The highest number recorded (in 1984) is no. 59, also signed and dated 1919: the University has nos 15 and 23 and a bronze version. She may also have been author of a posthumous plaster bust of Naruse, also at the JWU, which was finally cast in bronze in 1984 to mark its 80th anniversary. In 1920, at the second Teiten exhibition in Tokyo (successor to the Buntens) she showed Elisabeth (Florentine style), which is likely to have been a self-portrait bust, and in May that year a selection of her work was exhibited in the gallery of the Mitsukoshi department store in Tokyo with watercolours of Japan and Korea by Elizabeth Keith and prints by Charles William Bartlett, both known for Japanese subjects.

At present the last dated sight of her in Japan was in January 1922 when she shared an exhibition with a Czech painter referred to (in Japanese) as ‘Suk’ at Shiraki-ya in Nihonbashi, Tokyo. Her pieces were Three mysterious birds, Darkrose dance (bronze), A Lady from the age of Louis XVI and a A Lady from the age of Louis-Philippe. It seems likely that she left Tokyo in the wake of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, at latest. This demolished and burnt much of the city including the Bunka Gakuin school in the Ochanumizu district, a vocational one founded in 1921 on Western principles, backed by poets, writers and artists including Hakutei Ishii (who had sketched and interviewed her in 1917 for the magazine Chuo Bijyutsu). Its teachers included foreigners: Edward Gauntlett, a musician and linguist, was head of English and Tcheremissinof – noted in a Japanese article on it as ‘sculptor /pianist’ and ‘defected Russian aristocrat’ – was in charge of music, teaching piano and also foreign languages. Though only post-1917 Russian commissars might have called her ‘defector’ or ‘aristocrat’, she was by then an accidental exile likely to have needed the income that teaching would have augmented. (The school was soon rebuilt and continued until suppressed by Japan’s wartime government in 1943: it revived in 1946 and continued to 2018.)

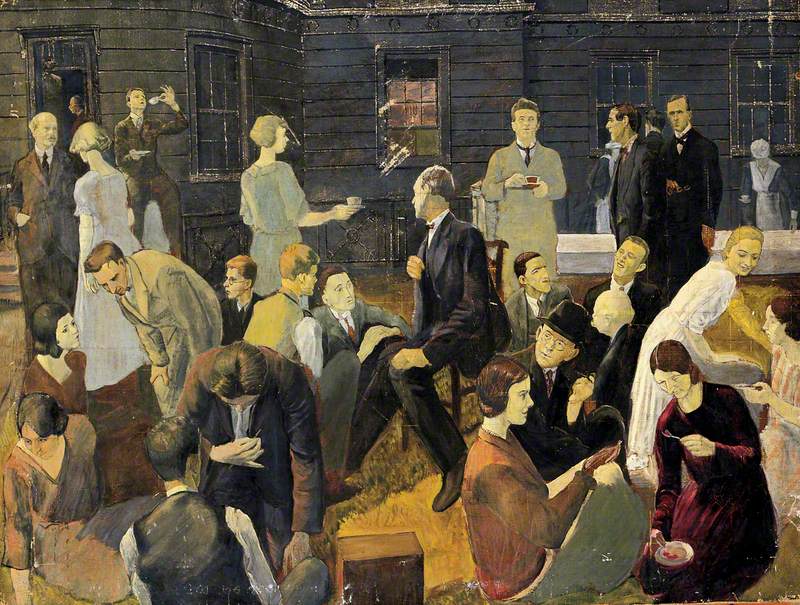

Her subsequent movements until 1937 are unknown but she perhaps returned to Austria given that her Count Kinsky portrait was then one of two exhibits at the Royal Academy in London. The other was an unidentified portrait bust and she submitted both from 5 Nevern Road, London, SW5. In 1937 she also did a large pastel portrait of the Indian cavalry officer Risaldar Major Lall Singh, MBE, when he was in London for the coronation of George VI as the King’s Indian orderly officer. She showed two sculptural pieces at the Royal Society of Miniature Painters in 1937 (no. 240, Miss Edith Andreae, a terracotta and no. 261, Last Chord, bronze) and one in 1938 (no. 302, Salome). From 5th to 19th May 1938, when at 11 Nevern Road, she showed 77 sculptures and paintings (landscapes and portraits, including that of Singh) in a solo exhibition at the Renaissance Galleries at 9 Lower Regent Street. Johnson and Greutzner list her just at 7 Nevern Road in both years and the landscape views in her solo show, including Czechoslovakia and Austria also suggest that central Europe was probably where she spent time between her return from Japan and arrival in London, though some (e.g. in Italy) could have been done earlier. Her often titled sitters and views of unfamiliar castles suggest a circle of European aristocratic contacts among whom she may have found refuge.

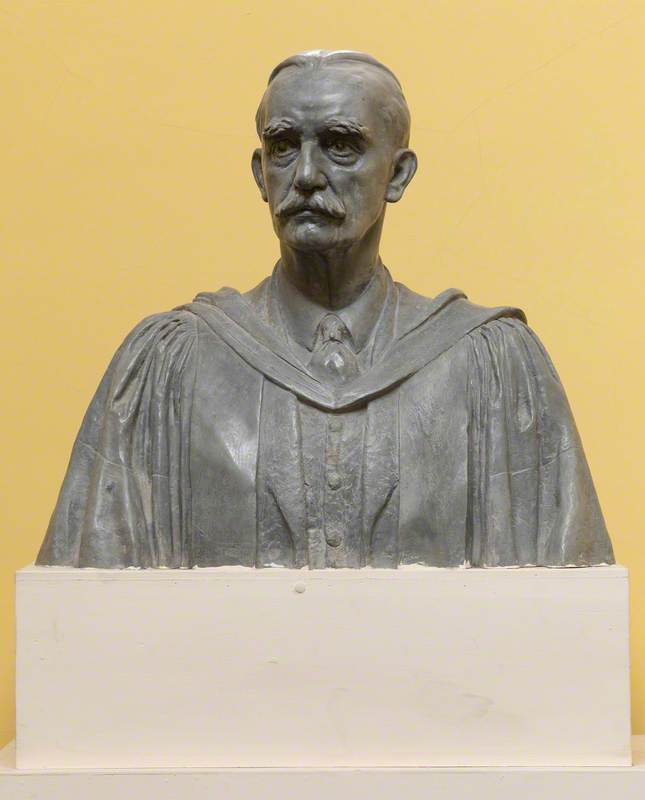

Her last RA exhibit, also in 1938 and illustrated in the catalogue, was an impressive lead bust of the former Headmaster of Winchester College, Montague John Rendall (1862–1950), who explained its genesis and her circumstances in a letter to the Warden of the College, dated 29th January 1939:

'I am told that a 'lead' bust of me, the work of a very talented and sincere Russian lady, Miss Tcheremisinoff, which was mentioned with strong approval by the press & received an excellent place in last year’s Academy, has been accepted by the Warden & Fellows – May I, in the first place, thank you and them warmly for finding a home for it somewhere in 'Win: Coll'. It is an honour which I did not expect.

Secondly, may I say that the making of the bust did not spring from any suggestion of mine. I was reluctantly induced to sit to Miss Tcheremissinoff at Madam Wockoff’s repeated request. Madame Wockoff has a son in College, whom the W. & F. accepted during Lord Selborne’s Wardenship. The two ladies have lately shared a studio in Kensington. They were & are sorely in need of financial help: that was why I came across them.

Madame Tcheremissinoff has made good friends with C[harles]. Wheeler R.A., the sculptor: also Herbert Baker [FRIBA, RA, the architect] has been very good to her.'

Rendall had a notable interest in the arts and was clearly prevailed on to help in difficult circumstances, probably through Wheeler, whom he knew well from work that both he and Baker had done for the College under his headmastership, from which he retired in 1924. College records say he presented the bust but also that it was paid for by a number of subscribing donors, probably former pupils. A complimentary note on it, and its recent appropriate positioning in the school museum for ‘the Headmaster who formed and cared for the original collection of Mediaeval and Renaissance sculpture’ there, appeared in The Wykehamist (no. 857, 13th June 1939).

Cheremisinova remained in London and the 1939 Register gave her studio address as 80 Warwick Gardens, Kensington. When she died at 9 Porchester Square on 8th February 1963 – apparently the eve of her 86th birthday – she left ‘effects’ of just £298 12s, probate being granted to her niece Ekaterina Petroff, with whom she was then living. Petroff – also an artist – was born in St Petersburg on 11th March 1908 as daughter of Elisabeth’s eldest sister Maria and Innokenti Petroff. She too had long been in London since also listed in Kelly’s Directory for 1939 (though not the September Register) at 80 Warwick Gardens. Rendall’s ‘Madam Wockoff’ also had studio space there (1937–38): she was more correctly Vera Nikolaevna Wolkoff (née Scalon), wife of the last Imperial Russian Naval Attaché in London (1913–1919), Rear-Admiral Nicholas Alexandrovich Wolkoff: both the Wolkoffs and Scalons were also St Petersburg families. Petroff (and presumably her aunt Elizaveta) was at Porchester Square when she became a naturalised British citizen in 1952 and remained on the electoral roll there until 1965. All these Kensington addresses were low-cost at the time.

On Ekaterina Petroff’s death in 1992, her heir was her cousin and Elizaveta’s niece, Baroness Martha von Rosen (b. Reval, Estonia, 1904–d. British Columbia, Canada, 2002), youngest of the three daughters of Anna Cheremisinova Kügelgen, Elizaveta’s immediately elder sister. Martha was co-author with her German husband, Baron Jurgen, of the Second World War memoir, A Baltic Odyssey: War and Survival (University of Calgary Press, 1996), edited by Elvi Whittaker from her reminiscences and his journal. Its preface also notes that Anna was both a well-known biographer and essayist but ‘most renowned, … as an icon painter, doing some of her best work in the later part of her life in Canada’. It reports that many examples are in the Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia. Anna died in Vancouver in 1966.

Cheremisinova was a talented daughter of privileged family, whose career opportunities and hard work appear to have fallen casualty to war and revolution, only briefly relieved by hitherto little-known prominence for at least five years in Japan. Though in England by 1937, and with family and other Russian connections there, the dislocations of exile and renewed world war in her 50s probably prevented her achieving the wider name and success she deserved.

Summarised from Art UK’s Art Detective discussion ‘What more could be established about the Russian sculptor Yelizaveta Cheremisinova?’. Updated September 2022, with thanks to Minako Sakakura for information found in Tokyo on the Bunka Gakuin school connection.

Text source: Art Detective