Belgian artist, writer, photographer, and film-maker, born in Brussels. He later lived and worked in Düsseldorf and London, and died in Cologne. In his early career, he worked mainly in the literary world as a poet, journalist, lecturer, and bookseller. He contributed to the Surrealist journal Fantomas and for a short period was a member of the Belgian Communist Party. He was one of the few to be honoured as a ‘living art work’ without qualification and without payment by Piero *Manzoni. He remained committed to a conception of modern art which had its origins as much in poetry as the visual arts, especially Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé. His early poems are an important reference point for the understanding of his work as an artist.

Read more

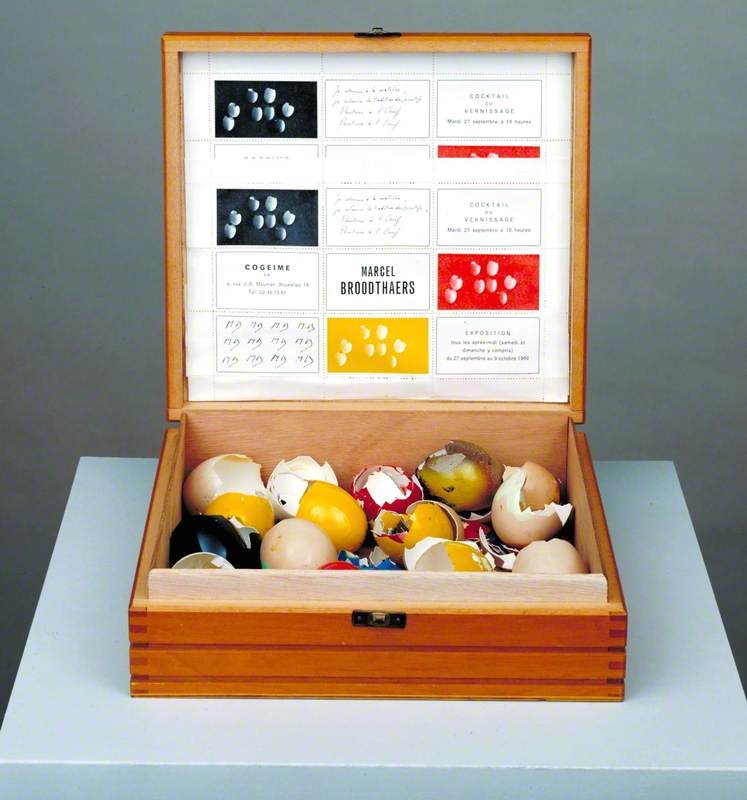

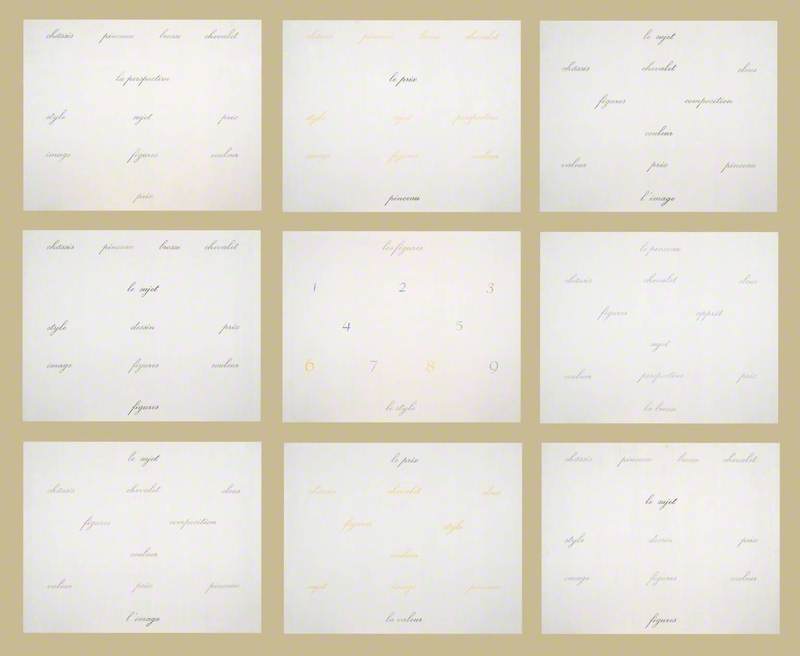

In 1964 he held his first exhibition at the Galerie St Laurent in Brussels. It included Pense-Bête, in which unsold volumes of his poems were encased in plaster. Turned into an object and rendered illegible, they became a sculpture and a marketable commodity. On the invitation card, Broodthaers mused that at the age of 40 he wondered ‘if he could not sell something and succeed in life’. Plaster was a material of topical significance. Broodthaers had been struck by the plaster life casts of George *Segal when they had been seen in Paris the previous year. Over the next few years he produced a series of objects which have something of the mixture of blandness and enigma of René *Magritte. The best-known example is Casserole and Closed Mussels (1965, Tate), an arrangement of mussel shells bursting in a neat column from a pot. Its appeal may be that it combines the straightforwardness of American *Pop with a certain sense of nostalgia. The casserole of mussels is the Belgian national dish. Pop art privileges the package above the content, as in *Warhol's soup cans; here the package is part of the ‘natural’ origin of the subject, an ironized European response to American cultural imperialism. Another motif was coal, a substance redolent of both the economic strength and the social misery of Belgium and northern France in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1968 Broodthaers was involved in the political and cultural turmoil of the time, taking part in the occupation of the Palais des Beaux Arts, Brussels. Later that year he mounted his own ‘Museum of Modern Art’ (Department of Eagles) in his Brussels apartment. This showed packing cases on which were projected slides of paintings by 19th-century artists. On the walls were postcards of their works. The museum, he argues, provides no refuge from the commoditization of art. At the same time he showed in Paris his ‘industrial paintings’, plastic plaques, which frequently referred to the museum. The selection of artists represented—David, Ingres, Courbet, and Wiertz—says something of his conception of the origins of modern art. This was, for him, not primarily a stylistic or formal development but a process by which the artist, while claiming freedom from the state, as Courbet did, becomes ‘moulded’ (‘moule’ has the double meaning of mussel and mould) by the market. Antoine Wiertz was a 19th-century Belgian painter, little known outside his own country, whose studio, now a museum, was a short distance from Broodthaers's apartment. His cultivation of large-scale work with sensational subject-matter in a studio provided by the Belgian state was a notable contrast to the direction modernist art actually took, with its dependence on the private market. Broodthaers closed his museum in 1972 but had already extended his activities into public museums and institutions. ‘Décor. A Conquest by Marcel Broodthaers’, held at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1975, was one of the most significant. By that time the institute had moved into Nash House, an early 19th-century building which overlooks Horse Guards Parade, and the exhibition was held in summer to coincide with the Trooping of the Colour, a military parade visible from the windows. The exhibition was staged across two rooms, one standing for the 19th, the other for the 20th century. In the first, the floor space was occupied by cannons and hand guns. Napoleon and Wellington (in the guise of crab and lobster) faced each other across a table. Around the walls were items of luxurious furniture from the period of the building. The adjoining room was dominated by a table with beach chairs; on the table the Battle of Waterloo had become a jigsaw puzzle, but around the walls were modern machine guns. The pleasant contemplation of past conflicts is still framed by violence. The museum has become instrumental in the seduction of society by leisure. Broodthaers also made films and books. The films differed radically from commercial narrative cinema, taking a form which demanded to be decoded by the spectator. Broodthaers was fascinated by the idea of the book as an object, as in A Voyage on the North Sea (1974), with its unopened pages. Although, like Joseph *Beuys, he was concerned to extend the technical and physical boundaries of art, the outlook of the two artists could hardly be more different. The German artist looked to human creativity to achieve some kind of redemption from the conditions of industrial capitalism. For Broodthaers art was moulded by language, the institution and the market place, so its capacity for intervention was limited. Out of this grim vision he made a black comedy of borrowed images. Further Reading A. Hakkens (ed.), Marcel Broodthaers par lui-même (1998) R. Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Media Condition (2000)

Text source: A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art (Oxford University Press)