Could you recognise a Luca Giordano when you saw one? The Welsh diarist and traveller Hester Lynch Piozzi (1720–1821) certainly could. Just a glimpse at the vast room where she was dining with twenty or so people was enough to recognise the three large history paintings that adorned the walls around her, in Palazzo Borromeo, Lake Maggiore in Northern Italy.

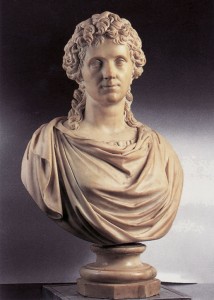

Hester Lynch Piozzi, née Salusbury, Later Mrs Thrale

1785–1786

unknown artist

That these canvases were by the Baroque Neapolitan painter Giordano rather than by Titian, a name, perhaps, more familiar to modern audiences, should not surprise either. It was 1784, and in London, prints of the Neapolitan master circulated in vast numbers, making him anything but unknown to art lovers of the time.

Perhaps what one could not imagine is that, despite her sensibility and understanding of art, languages and literature, Hester did not receive a formal education. However, like most women of her time, Hester was interested in extensive reading, and cultural activities; she attended art auctions in London and provided her own artistic education, despite society often frowning on women like her.

This, it goes without saying, was not always enough. It was only through continental travel that women could affirm themselves as acute writers and accomplished art connoisseurs. Typically accompanied by their husbands or brothers – and if widowed, by other female companions – women could, from around the 1750s, finally embark on their Grand Tour to the continent.

A View of the Gulf of Pozzuoli and the Bay of Baia beyond with Capo Miseno, Procida and Ischia

Gabriele Ricciardelli (d.1777)

While in Italy, women were usually never left alone, and as expected, their public appearances depended on the availability of husbands or chaperones. Not only that, but certain spaces were inappropriate for a lady to even be present. Churches, art galleries and artists' studios were usually preferable to muddy, perilous journeys inland, undertaken by their male counterparts.

However, suppose the footsteps of the Latin poet Virgil were considered too large for their aristocratic shoes; in that case, one cannot forget that Virgil himself could not cross the underworld without the help of a knowledgeable and fearsome woman, the Cumaean Sibyl.

Despite being dusty, and certainly not suitable for an unaccompanied woman, Lady Anna Miller (1741–1781) visited Pompeii with her husband in February 1771. Anna did not limit herself to touring the excavations; instead, she appealed to the apprehensive Bourbonic guards and secretly copied frescoes and inscriptions at their back – a practice severely forbidden at the time.

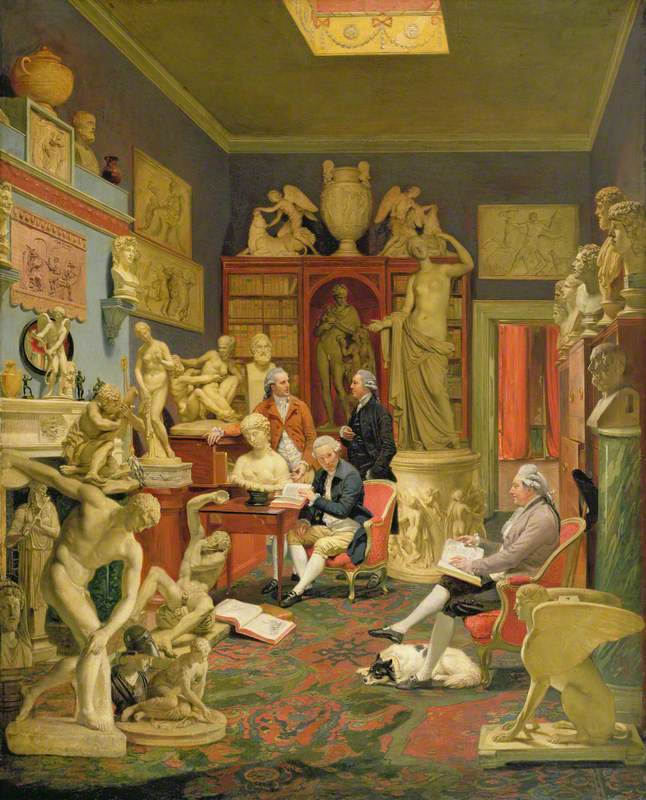

Was it not the thrill and excitement of the forbidden that amplified the allure of ancient civilisations? Certainly, Vesuvian discoveries sparked a revival of interest in antiquities. Inevitably, the collecting preferences of Grand Tourists changed, beginning to focus increasingly on archaeology and ancient artefacts. Johann Zoffany captures this in his depiction of the art expert Charles Townley in his London library, surrounded by ancient sculptures found on his travels to Italy.

Charles Townley and Friends in His Library at Park Street, Westminster

1781–1790 & 1798

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

Marble sculptures, decorated vases, engraved gems, cameos and coins soon overshadowed the Baroque frescoes and canvases admired in the early eighteenth century when dozens of canvases by Salvator Rosa, Luca Giordano, Francesco Solimena and other Neapolitan masters – such as Paolo de' Matteis (a pupil of Giordano) – were commissioned by English Grand Tourists.

Artworks, like those below, were rolled up and shipped from Italy to the shores of England, intended to adorn the empty walls of grand English country manors and sumptuous London houses.

Christ Expelling the Money Changers from the Temple

1660s

Salvator Rosa (1615–1673)

The Parable of the Prodigal Son: The Fatted Calf

early 1680s

Luca Giordano (1634–1705)

In this ever-changing movement of art from Italy to Britain, women played a significant role, though their contributions were, and have been, often overlooked.

Portraiture ranked highly within women's artistic expertise, and it allowed them to sit without the presence of men under the protected and privileged light of artists' studios – often those of women such as the praised portraitists Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun and Angelica Kauffmann.

Lady Hamilton (1761–1815), as a Bacchante

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842)

During their Roman and Neapolitan sojourns, numerous women, including Lady Hamilton and Mrs Russell, commissioned from them mementoes to bring back home, trusting their ability to emphasise their feminine and intellectual identity. Books, sculptures and musical instruments became a means to show their literary and artistic ambitions.

Mrs Russell (1707–1764), Wife of Colonel Charles Russell

Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807)

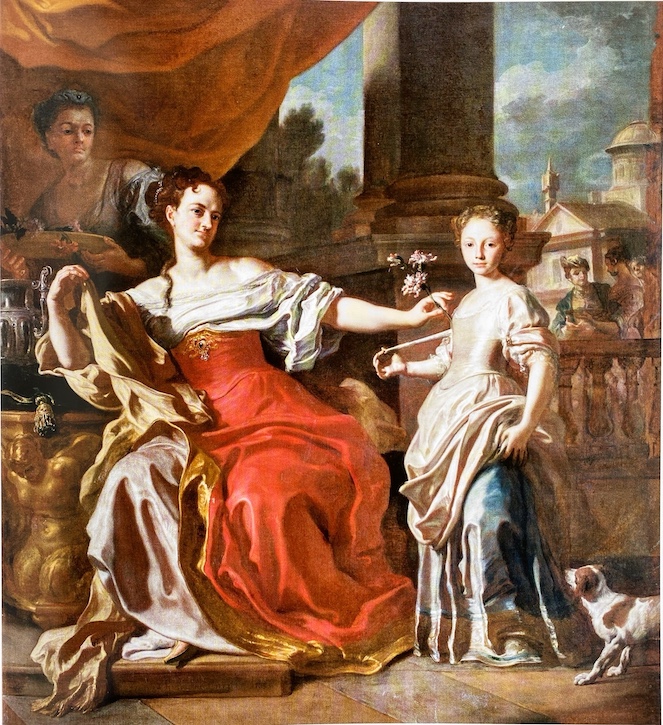

Certainly, some men were also capable of similar attention and finesse. Among them was the Neapolitan master and celebrated portraitist Francesco Solimena, who in 1733 bathed Lady Susanne Strangways and her ten-year-old daughter in the golden Mediterranean light of a Baroque-enchanted Naples.

Susanna Strangways Horner and her daughter Elizabeth in Naples

1733, oil on canvas by Francesco Solimena (1657–1747)

The worldly elegance of Lady Susanne blends with the crowd beyond the balustrade, while the table on the left evokes a classicism that, soon enough, would outshine even the most esteemed Baroque brushes, such as those of Solimena himself and Giordano before him.

Far from merely collecting superficial embellishments, jewellery and fancy dresses adorned with cameos and matching fans to show on promenade walks, women found themselves as 'paladins' of Baroque art, revealing unconventional preferences that contrasted with the antiquarian taste of their male counterparts.

While Elizabeth Gibbes (c.1761–1847), who travelled through Italy with her family between 1789 and 1790, dismissed antiquities as 'nothing in particular', another woman, before her, dared to criticise male preferences. Anna Miller (1741–1781) accused the influential French art critic Charles-Nicolas Cochin (1715–1790) of absurdity for overlooking the art of Luca Giordano.

Anna was not afraid to describe Giordano as ingenious and admirable, capable of stirring her emotions and striking her mind with works such as The Rape of the Sabines, which captured her attention in Palazzo Balbi, Genoa. The Bristol Museum and Gallery houses a similar version of the Giordano work that enraptured Anna.

Two decades later, the traveller and writer Mariana Starke (c.1762–1838) introduced an innovative system in her practical guide to prevent travellers from missing out on artworks, palazzi or historical gates that, in her critical opinion, deserved closer attention. Using a scale of three exclamation marks, which later inspired the use of asterisks in some modern guides, she awarded two to the frescoed ceiling depicting the 'Triumph of Judith' by Giordano in the Neapolitan Certosa of Saint Martino.

The Bowes Museum, in Barnard Castle – the collection of which was amassed by art enthusiast Joséphine Benoîte Coffin-Chevalier alongside her husband – likely houses one of the preparatory sketches for the episode of the victorious Judith depicted on one of the sides of this late, airy and luminous composition by Giordano – although some details may differ from the final version.

Through exclamation marks used to highlight worthy paintings, or comments made to guide those in Britain who wished to commission or acquire art in Italy, women contributed to the nascent field of art criticism and ongoing interest in Baroque paintings, despite the discoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum driving the consequent craze for antiquities.

Women were witty writers, art experts and sharp collectors, no less than their male companions. Accused of unreliability, lack of accuracy, susceptibility to emotional responses or being overly 'extravagant', women proved themselves accomplished, sensitive and modern art critics through their diaries, accounts and art commissions.

Lady Margaret Tufton (1700–1775), Countess of Leicester, Baroness Clifford

(c.1744–1758), oil on canvas by Andrea Casali (1705–1784)

Among them, Margaret Coke, Countess of Leicester (1700–1775), for example, distinguished herself as one of the most remarkable curators for Holkham Hall – where she lived with her husband Thomas Coke – and its enviable collection of Neapolitan and Italian pictures. She also commissioned new works, including two paintings by Giovanni Battista Cipriani for the Chapel.

These stories show how women not only could advise the British in their collecting choices but also act as passionate curators capable of administrating, arranging and expanding their timeless family collections.

Alessia Attanasio, art historian

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation