This essay was written for the 2018 Write on Art prize, winning second place in the Year 12 & 13

Instagram. Traffic lights. Times Square. The bright yellow box of Coco Pops confronting you in the kitchen cupboard.

Step back from the seething mass of

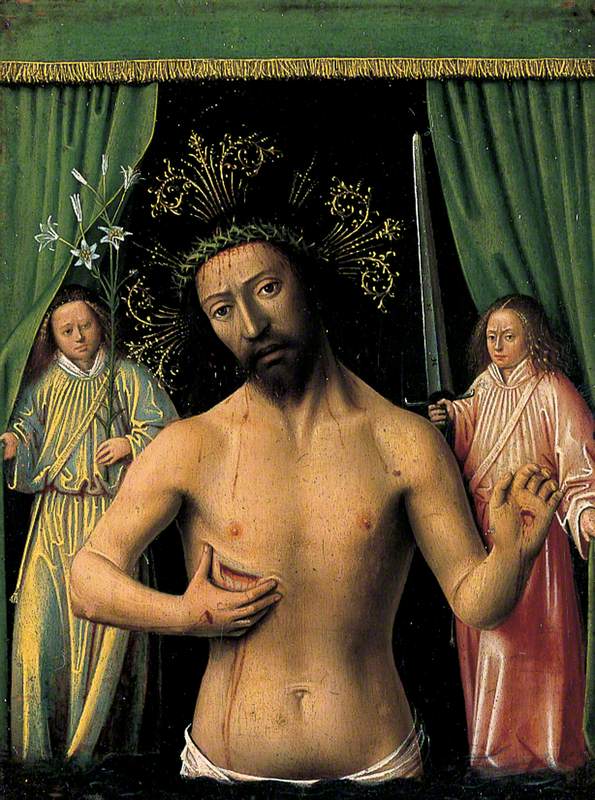

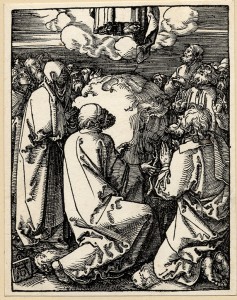

Painted in Seville at the height of the Counter-Reformation, this work is devoutly religious and hugely disarming. It searches us, questioning, like a severe security guard at the airport: why are you

Or perhaps more aptly: why do you live? Who do you believe in? And where will you go when you die?

Saint Francis was the subject of many paintings by Spanish artists during the Counter-Reformation, largely due to the pious transformation involved in his story. Originally a wealthy merchant’s son living in opulence, he renounced all worldly goods following his conversion to Christianity in the early 1200s. For the Council of Trent, which met in the years 1545–1563 and promoted art that encouraged Protestant wanderers back to the Catholic faith, this embodied the attitude of life-altering repentance which they wished to inspire. In this desire, works of the Counter-Reformation often strove to involve the viewer with a clear narrative, drama

Zurbarán’s work here seems to

Yet despite this, Zurbarán seems to take the emphasis away from Saint Francis himself. The stigmata, so entrenched in Catholic perception of him, are barely visible: a faint mark, just distinguishable on his right hand, the only hint at their existence. The cord of Saint Francis, which traditionally held between three and five knots to

Perhaps most significantly, the shadow from his Capuchin cowl plunges his face into darkness, his nose and mouth the only features touched by the light. Unlike many other depictions of Saint Francis by artists such as Caravaggio and El Greco, Zurbarán’s saint doesn’t focus his meditation down towards a crucifix, book or the skull in his hands. Instead, though death yawns up at him in the latter’s empty eye sockets, Saint Francis turns his face to God; lips parted in awe as he is caught in the moment of release and redemption. He is clearly undergoing an intense psychological experience, yet in contrast to the torment of later works like The Scream by Munch or Courbet’s The Desperate Man, Saint Francis doesn’t stare out of the canvas in emotional agony. Instead, there is a direction and peace implied in his gaze: he isn’t looking for

Why are you

From where and to whom?

Zurbarán presents a clear choice: to kneel with Saint Francis in the

Felicity MacKenzie