Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950) was born in Le Havre, France, to a French father and Scottish mother. During her lifetime her works in printmaking and oil painting would be held in high regard by an early to mid-twentieth century art establishment. Her perseverance in perfecting her technical abilities was particularly significant, but it was the consideration of her subject matter that was perhaps the most notable.

While France remained Gabain's main home until the age of twenty, her adolescent education took place in Britain, where she attended the boarding school Wycombe Abbey School, Buckinghamshire. Her initial aptitude for art was rewarded with her first commission, to paint a portrait of the school's headmistress. The experience of schooling in the home counties also equipped the young artist with the language skills and cultural knowledge to later move to England.

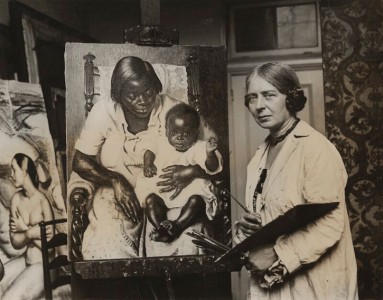

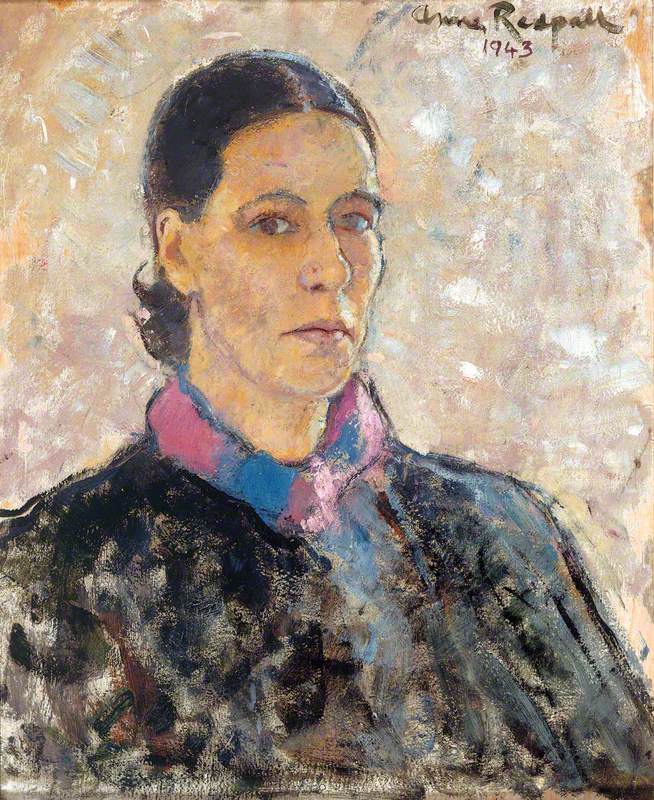

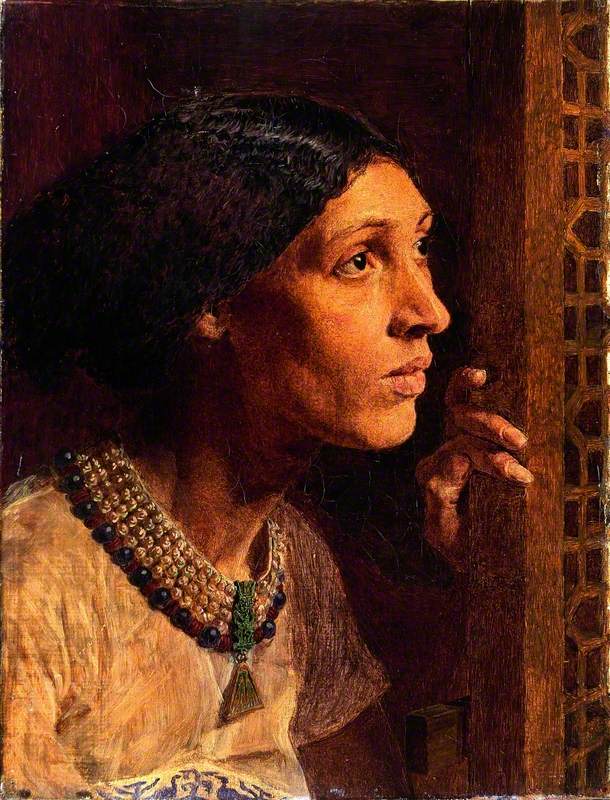

Photograph of Ethel Gabain

1913, photograph by Peter Copley

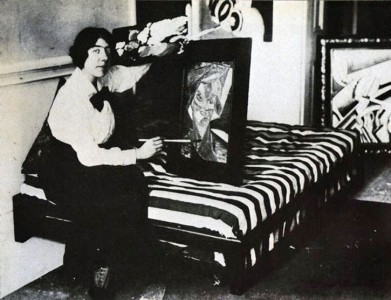

Gabain began her adult art studies at London's Slade School of Fine Art in 1902. This was followed by a period of education at Raphaël Collin's studio in Paris, before returning to England in 1904 to train at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. Here she was first introduced to lithography, a form of printmaking involving printing from a metal plate or smooth stone. It was an art form that would become particularly important to Gabain.

Woman Putting on Her Shoe (Une dame qui se chausse)

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

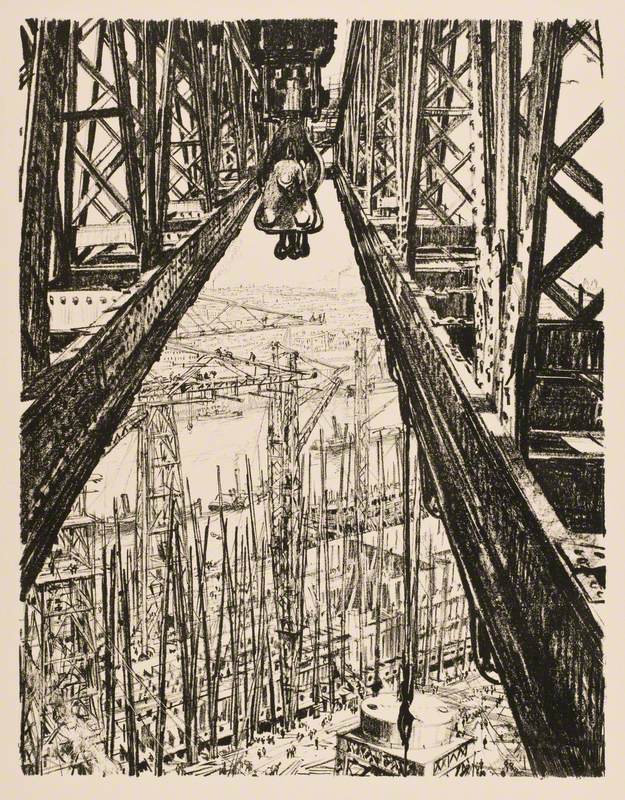

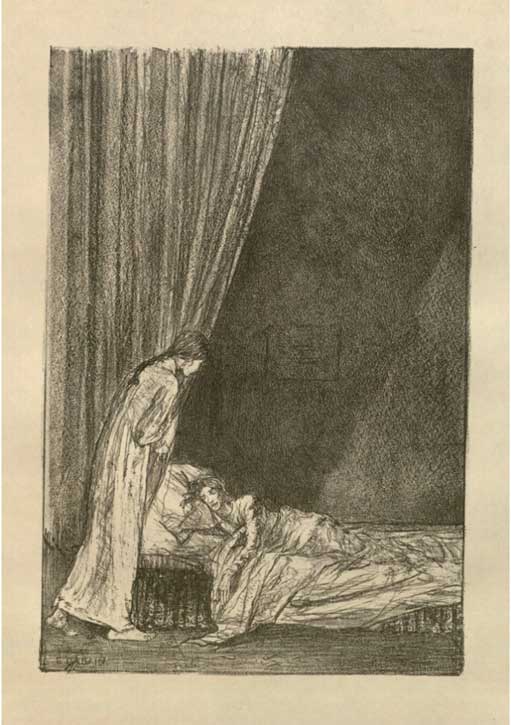

Instantly drawn to the idea, the artist began to experiment with the medium in conjunction with acquiring first-hand technical experience of the printing processes. Perfecting lithography techniques and attaining a high level of technical knowledge became key to Gabain's practice. She eventually gained a reputation for being a fine draughtswoman. Lithographs in simple, yet stark, black and white became her expression of choice, while a focus on the lone female subject became her trademark.

In 1906 Gabain exhibited her prints at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. In 1909, accompanied by her future partner, John Copley and several fellow artists, Gabain co-founded The Senefelder Club, a London-based organisation created to promote lithographic techniques. Their first group exhibition, including six artworks by Gabain, was held in the capital the same year.

The Silken Wrap

1916, lithograph on paper by Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

Gabain continued to perfect her work by studying with both British and French experts in the printmaking field. During the interwar period, the artist's lithographs gained a positive reception and she was able to make a reasonable living from their sale. This was both unusual for a woman artist and for her chosen medium.

Her concentration on the female subject positioned in seclusion within a sparsely decorated space persisted and, despite an air of melancholy, the work proved to be popular. In particular, the theme of the 'sad bride' became a recurrent one. In 1922, her prints were chosen to illustrate an edition of Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre.

The cover of 'Jane Eyre'

1923, lithograph on paper by Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

In 1925, Gabain's husband became ill and required a period of convalescence. This caused the family, including two sons, to relocate from their Hampstead home to Alassio, Italy. Gabain's creative output was subsequently impacted. She began to encompass influences from the Italian landscape within her work, while also lecturing at the English schools of the area during the two years the family remained there. Significantly, Gabain began working in oil painting around this time – a crucial turning point in her career.

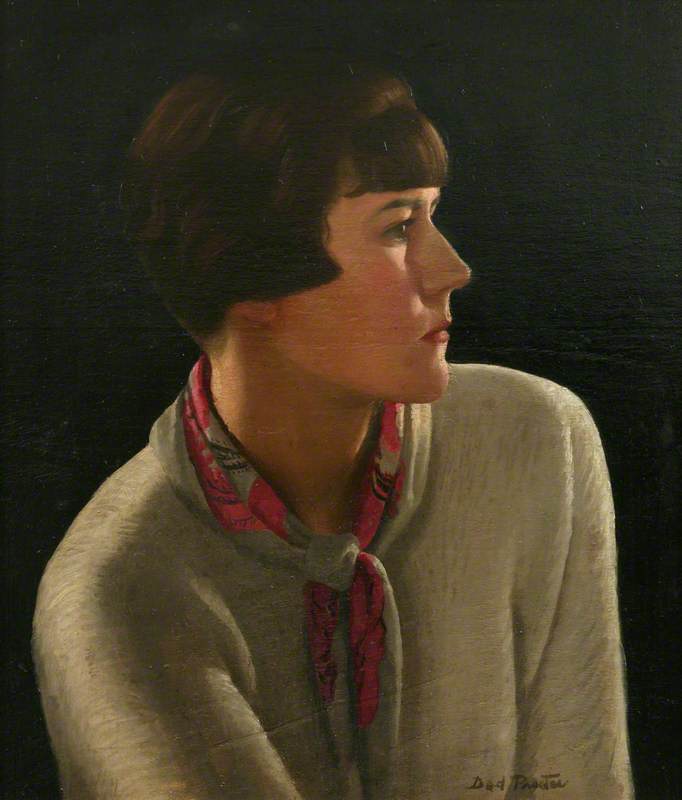

While prints were becoming a less popular art form for sale, paintings retained their cultural momentum. Gabain found the transition from one medium to another a comfortable one. Her first attempts at painting floral themes were met with approval from the art establishment. While also experimenting in areas such as landscapes, it was Gabain's adoption of portraiture that earned her the greatest attention.

During the 1930s the artist began a series of paintings focused on popular actresses of the age, including well-known names such as Flora Robson and Peggy Ashcroft. Her subjects were captured often in costume and presented as if in character. This is apparent in Peggy Ashcroft as Juliet, London, 1935 (from 'Romeo and Juliet'), a three-quarter length, standing portrait reflecting the actress against the backdrop of a theatrical curtain.

Peggy Ashcroft (1907–1991), as Juliet, London, 1935

(from 'Romeo and Juliet') c.1935

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

Likewise, a similar three-quarter length work entitled Miss Flora Robson as Lady Audley, 1933 which features a seated Robson in the elaborate attire of her character, was another of Gabain's subjects. All were praised and the latter was in fact granted the De Laszlo Silver medal by the Royal Society of British Artists.

As her thematic focus on lone women continued, typified in paintings such as At a Sunny Window, Gabain was elected to the Royal Society of British Artists and also the Royal Institute of Oil Painters.

Her inclusions in exhibitions at establishments such as the Royal Academy and Paris Salon had been frequent over the years, and she continued to contribute to shows organised by the Artists' International Association. By 1940, her successful election to the post of President of the Society of Women Artists was another sign of her status within the art establishment.

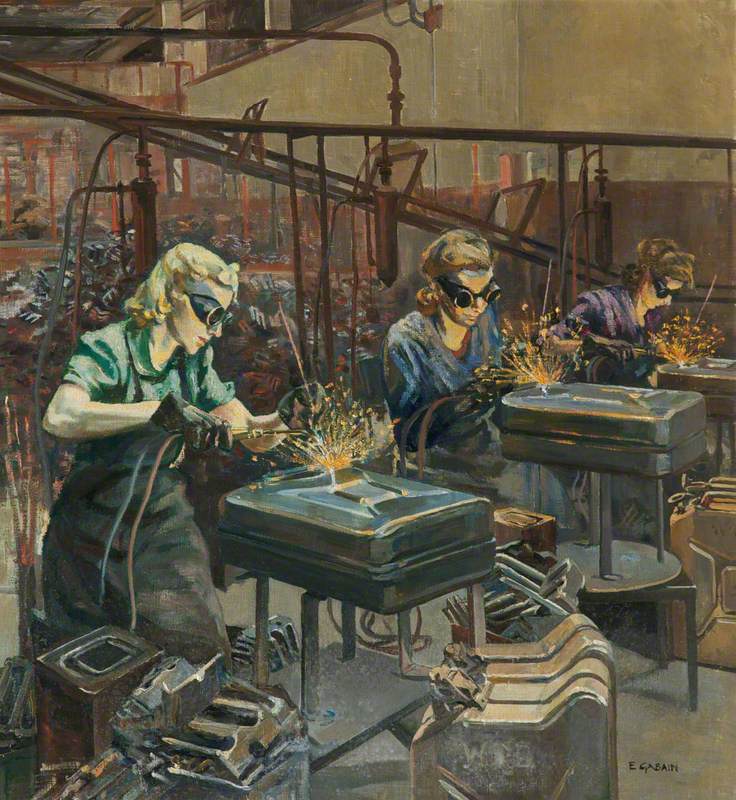

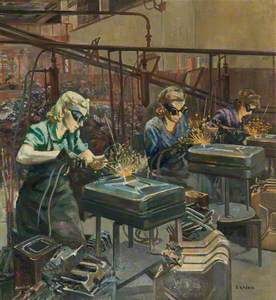

During the Second World War, Gabain was employed by the War Artists' Advisory Committee. Her role was to reflect the imperative work of female workers, particularly those who had taken on the various work and responsibilities of enlisted men.

Examples of the paintings she produced included the industrial commissions of Women Welders at Williams & Williams, Chester, a work depicting women on the factory floor and Women Workers in the Canteen at Williams & Williams, Chester reflecting the same workforce during a break.

Women Workers in the Canteen at Williams & Williams, Chester

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

Unlike her earlier prints featuring inactive, and lone female subjects in monochrome, Gabain's oil paintings became compositionally busy with themes of the communal labours of women, presented in vibrant colour.

Sandbag Filling, Islington Borough Council

c.1941

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

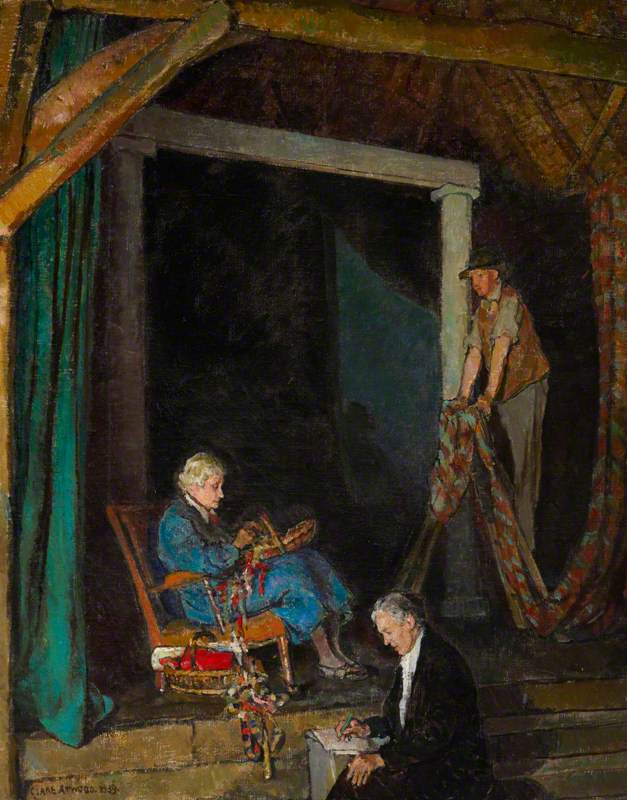

When creating work such as Sandbag Filling, Islington Borough Council (1941), Auxiliary Fire Service Girl, City Fire Station, and A Crèche (1942), Gabain continued to reflect female subjects in both traditional and non-traditional occupational roles, in a realist style appropriate for documentation.

Auxiliary Fire Service Girl, City Fire Station

1940

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

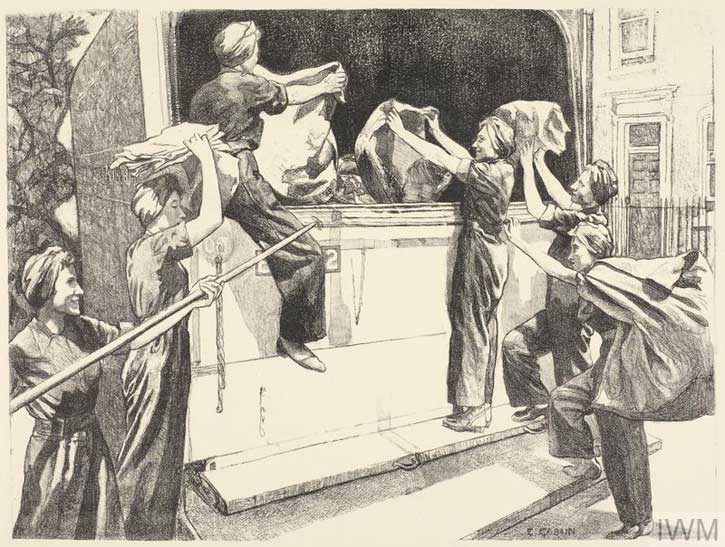

Similarly, the lithographs she produced during this era – created on her travels throughout the British Isles – also captured the range of women's contributions on the home front.

Salvage Workers Women's Work in the War (Other than the Services)

1941, lithograph on paper by Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

Despite producing some portraits of men and children, such as the paintings Child Bomb Victim Receiving Penicillin Treatment (1944) and The Airman (1937), her focus on female subjects continued.

A Child Bomb Victim Receiving Penicillin Treatment

1944

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

From portraying nurses in Hospital Supply Depot at Roehampton Club (1940) to portraits of female pilots such as that of Captain Pauline Gower of the Women's Air Transport Auxiliary in the Imperial War Museum, Gabain chronicled the new era of working women.

Hospital Supply Depot at Roehampton Club

1940

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

In the post-war period, the artist continued to paint portraits of notable women, such as that of Dame Mary Latchford Kingsmill Jones, first female Lord Mayor of Manchester. She also returned to her previous focus on lone subjects with an atmosphere of melancholia.

Dame Mary Latchford Kingsmill Jones

1947–1950

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

The pale and ghostly subject Gabain portrayed in The Bride and the Canary (1950), was created at a time of the artist's own failing health. Gabain died not long after she completed the painting and her passing was marked by a memorial exhibition at the Royal Society of British Artists in London.

While remembered for her technical skills in both printmaking and oil painting, Gabain's main legacy is arguably that of a well-respected artist who presented an intriguing and multifaceted vision of womanhood during the early twentieth century. Unlike the majority of successful artists of that era, she offered a particular and dignified statement about the lives of fellow women, from their pre-war isolation to their achievements in the arts, and finally their valuable contributions during the war effort.

P. L. Henderson, art historian and founder of @WOMENSART