In 1969, Tate bought Willem de Kooning's large oil painting, The Visit. The painting depicts a squatting female figure with a distorted face and splayed legs, whose limbs dissolve at their extremities into the masses of colour and brushwork that surround and intersect her body.

In the upper right-hand corner of the canvas there seems to be a second figure, whose face and eye might also be interpreted as the woman's raised fist. It is this second figure who gave the painting its name, when one of de Kooning's assistants linked The Visit to religious iconography of the Annunciation: the squatting figure as Mary, her splayed thighs evoking childbirth, and the second figure the angel delivering his message.

Critics of de Kooning's paintings of women might accept that bourgeois values are being challenged, but inquire why a man's radical grandstanding, whether artistic or political, is taking place over and through the body of a woman?

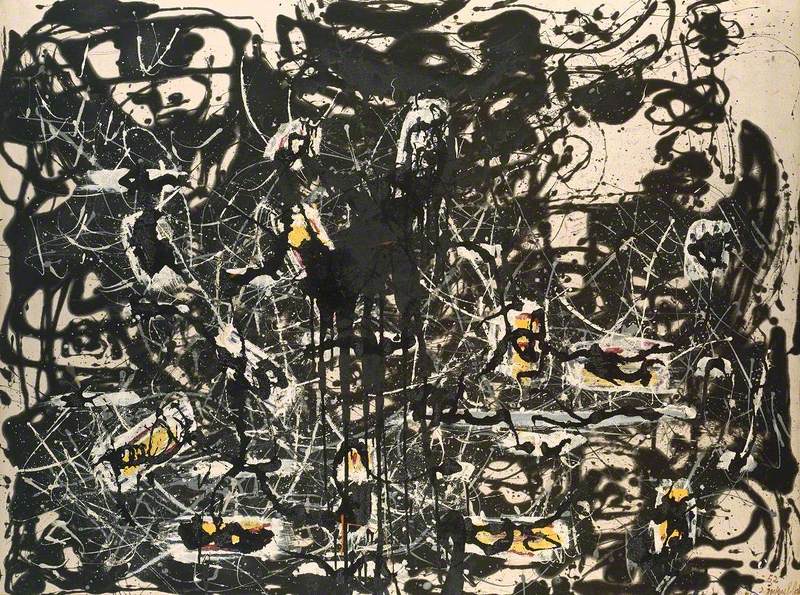

It is interesting to look at the events leading up to Tate's purchase. De Kooning had achieved fame through his participation in the Abstract Expressionist fever in New York in the 1940s and 1950s, an avant-garde 'moment' contributed to by several quite different artists who shared a commitment to producing abstract, rather than subject-driven, art. De Kooning's most notorious painting was Woman I (1950–1952), the first in a series of paintings of the same subject.

These paintings not only departed radically from abstraction, but were startlingly aggressive in the way that de Kooning used paint to create and mutilate the female figure. Some thought de Kooning's style was regressive, or that the way he approached his subject was aggressive towards women, but the dominant view was the 'Woman' series was a radical and valuable moment in avant-garde history.

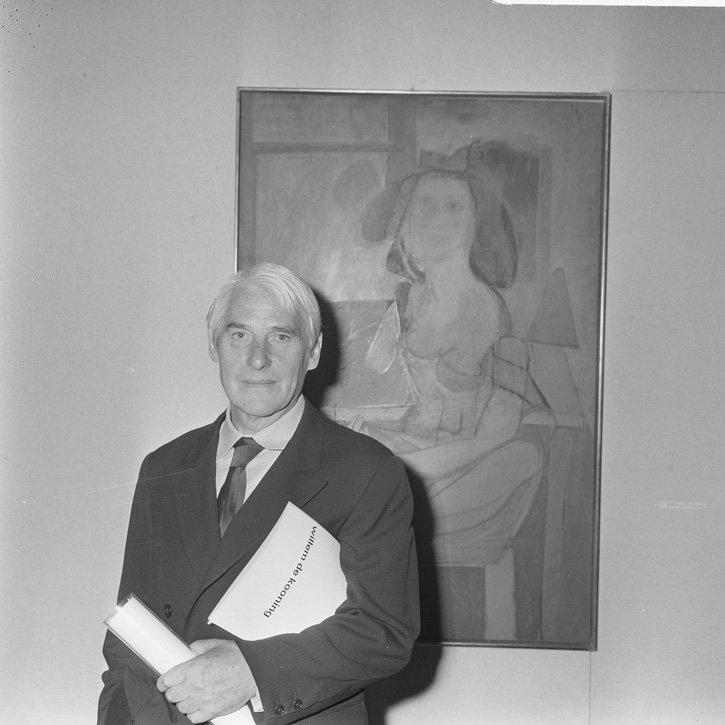

In 1968 de Kooning was given an international retrospective that travelled between the Netherlands, the UK, and several locations in the United States. Tate itself hosted the exhibition, which included The Visit. The retrospective effectively canonised de Kooning and likely alerted Tate to the need to acquire one of de Kooning's works for its own collection. The similarities between The Visit and de Kooning's infamous 'Woman' series of paintings probably recommended this painting to Tate, who bought it with the help of a donation in 1969.

To look at, The Visit is an aggressive painting: the implications of motherhood are made grotesque by the woman's fanged face, thrust forward at the neck, from which stare one blind and one gigantic eye. The Visit has not been written about as much as the 'Woman' series, which sparked huge controversy, and which continues to be criticised and defended. However, lots of the thinking about Woman I and her sisters can usefully be brought to bear on The Visit.

Willem de Kooning

19 September 1968, photograph by Jac de Nijs

Defenders of the 'Woman' series argue that de Kooning's real interest is stylistic and that his paintings blend abstract and figurative elements in a way that was radically shocking to the 1950s art world. Furthermore, the argument might be that the aggression is not aimed at women per se, but rather, he is attacking the idealised feminine type that was forcefully promoted by advertisers and Hollywood.

De Kooning's work has been placed within a narrative that interprets modern avant-garde artists as diametrically opposed to bourgeois (Victorian) values, which promoted the feminine, and motherhood in particular, as integral to that most bourgeois and reactionary of concepts: the family. This narrative, whereby de Kooning emerges as a heroic and progressive radical, is complicated by de Kooning's own assertion in 1956 that 'I was exploring the woman in me' or, contrarily in 1975 that he 'never gave much thought to their proper gender.'

Critics of de Kooning's paintings of women might accept that bourgeois values are being challenged, but inquire why a man's radical grandstanding, whether artistic or political, is taking over and through the body of a woman? The female nude has long been considered a mainstay of art production, as though it were a blank canvas on which artists (usually male) could test and demonstrate their skill.

However, feminist art historians have exposed the fallacy of this position, arguing that the extensive use of a female subject should be viewed as an exclusionary practice which prioritised a heterosexual male perspective. Furthermore, the obliteration of the feminine ideal by a man smacks uncomfortably of misogyny as much as of artistic licence.

These debates raged (and continue to rage) in the 1950s and 1960s. During this time de Kooning was also compared favourably with Picasso, whose combinations of figural and abstract elements had made him 'the man to beat' for de Kooning earlier in his career. It is possible that with The Visit, which was painted 15 years after the first 'Woman' paintings, de Kooning is addressing the arguments of his detractors and the praise of his critics.

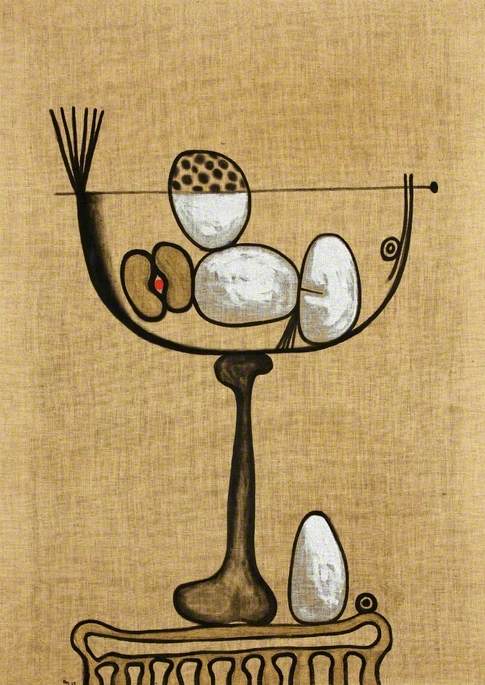

The Visit explicitly takes a maternal figure as its subject, and channels the squatting female figure in Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907). At Tate, the nation has a painting that maps so perfectly the issues at stake during the furore over the 'Woman' paintings that it is hard not to infer that The Visit is the result of de Kooning having paid attention.

Victoria Ibbett, writer

.jpg)