Albrecht Dürer was born on 21st May 1471 in Nuremberg (Nürnberg), a thriving town in what is now southern Germany – then part of the Holy Roman Empire.

He was to become the leading figure of the Northern Renaissance, and his incredible art still resonates today. Here are a few facts about Albrecht Dürer.

1. He trained as a goldsmith

He was born the third of 18 children to Albrecht Dürer senior, who was a goldsmith, and Barbara Holper, whose father had employed the elder Albrecht.

The young Albrecht was also trained as a goldsmith but excelled at drawing. His early self portrait, created in silverpoint when he was just 13, shows a mastery of this unforgiving and extremely technical medium.

Self Portrait at Age 13

1484, silverpoint drawing by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

At 15, Albrecht was apprenticed to the painter Michael Wolgemut and began to learn the artistic techniques he would employ in his career, from drawing and painting to woodcut printing, which was used for book illustrations among other things.

In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, Nuremberg was the economic capital of Germany. It was wealthy and exported gold and silverwork throughout Europe. It meant that the city was one of the first to have printing presses and this was to be crucial in Dürer's art.

2. He took a gap year and travelled

Although Nuremberg was a cosmopolitan hub, it was customary for artists to gain experience after their apprenticeship by travelling around, learning from others – a kind of gap year. Dürer left Nuremberg in 1490 and did not return until 1494.

He travelled through Germany to Colmar, Basel (where he worked as a book illustrator) and Strasbourg, returning briefly to get married, but leaving again after a couple of months to visit northern Italy.

Landscape by Albrecht Dürer, who was born #onthisday in 1471. While most of his work consisted of oil paintings and woodcut engravings, Dürer also painted a number of watercolour landscapes in his travels to and from Italy, particularly in the Alps of southern Tyrol, Italy pic.twitter.com/rg1I4WWgfc

— Ashmolean Museum (@AshmoleanMuseum) May 21, 2019

He made watercolour sketches of the landscape as he crossed the Alps, and spent time in Venice where he became familiar with the great artists there – above all Giovanni Bellini, but also Pollaiuolo, Lorenzo di Credi and Mantegna.

He returned to Nuremberg in 1495 and opened his own workshop where he produced paintings, woodcuts and engravings. He soon became the city's leading artist.

3. He excelled at woodcuts and engravings

His training as a book illustrator gave Dürer an insight into how to make woodcut prints, but it was his artistic genius and astonishing draughtsmanship that enabled him to take the medium to a new level.

Woodcuts and engravings are slightly different processes of making prints, but Dürer was to excel at both. He made various series of woodcuts, including the 'Life of the Virgin' (a series of 20 scenes including frontispiece) and the 'Small Passion' of 1511 (a series of 37 scenes from the life of Christ).

This print in the Ben Uri Gallery shows number 17 in the sequence of the 'Life of the Virgin' – Christ taking leave of his Mother.

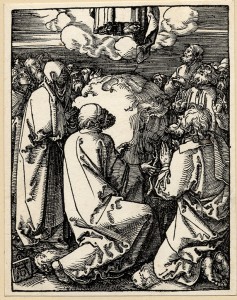

Whereas this (from a complete set of the 'Small Passion' in the British Museum) depicts number 35 in the sequence – Christ's Ascension, with Jesus's feet disappearing at the top of the image.

The Ascension of Christ

c.1510, woodcut by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

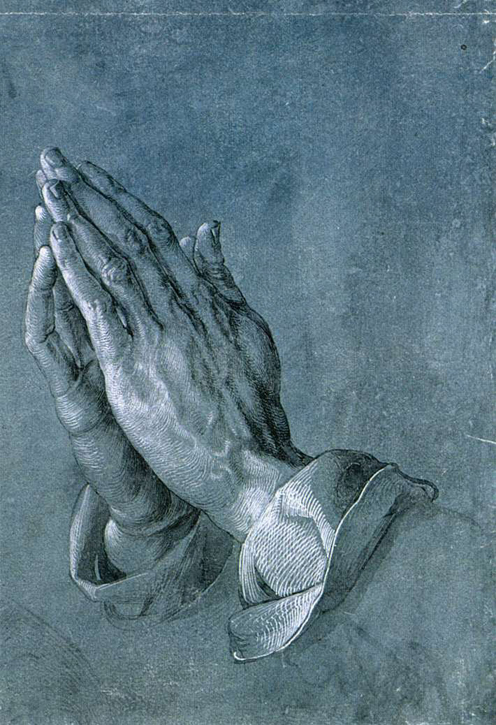

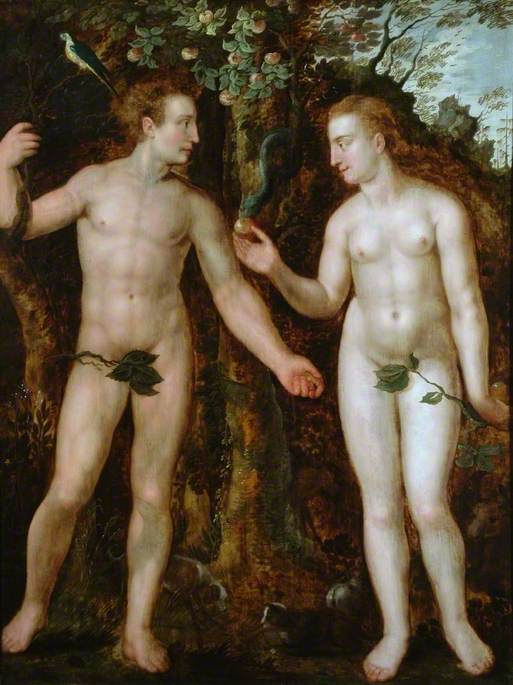

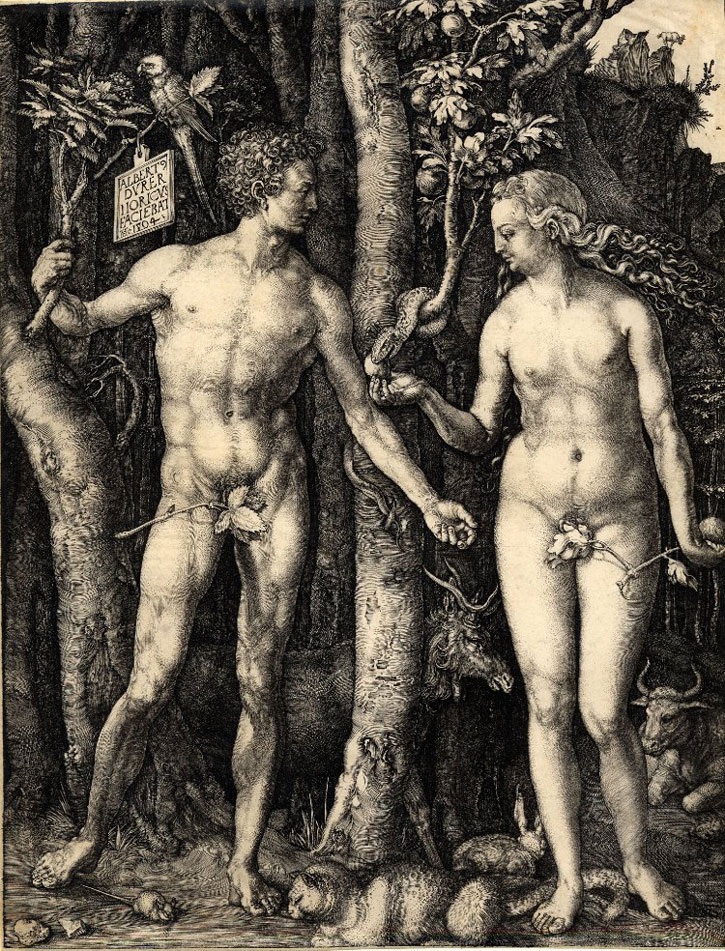

One of Dürer's most famous engravings is of Adam and Eve, and dates from 1504.

Adam and Eve

1504, engraving by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

It is incredibly detailed, with human skin, snake skin, animal fur and tree bark all rendered through the medium of engraving. Dürer's fascination with ideal form can be seen in this work. The figures are shown in nearly symmetrical idealised poses – each with the weight on one leg, the other leg bent, and each with one arm angled slightly upward.

Four of the animals represent the medieval idea of the four temperaments – yellow bile (the cat), blood (the rabbit), phlegm (the ox), and black bile (the elk).

In 1507 Dürer would paint the same subject with a similar composition, which is now in the Museo del Prado.

4. He used remarkably detailed preparatory drawings

Throughout his career, Dürer would continue to use detailed preparatory drawings, and also use watercolour and bodycolour. This is a preparatory drawing for a commission from the city of Nuremberg.

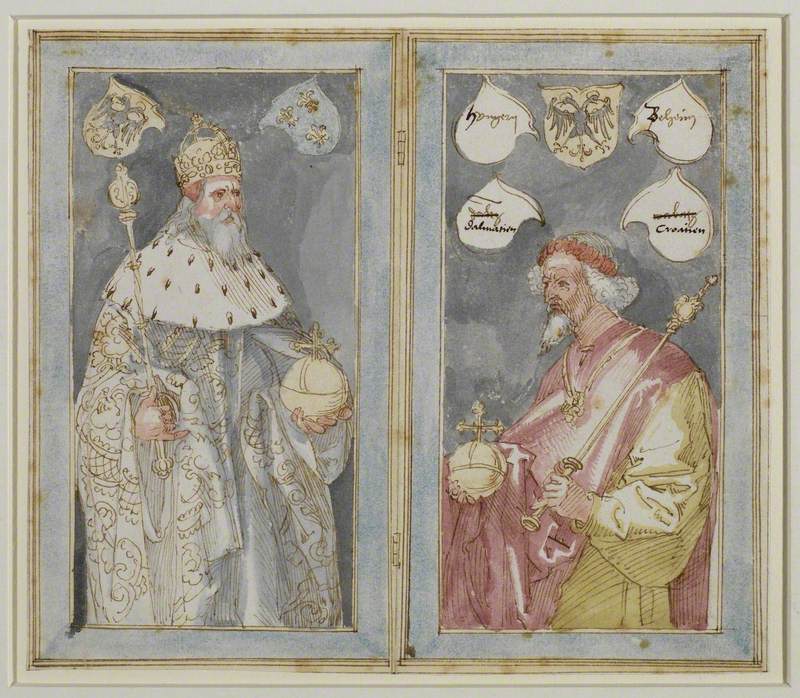

Emperors Charlemagne and Sigismund

1507–c.1510

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

It shows the founder of the Holy Roman Empire, Charlemagne (748–814) on the left, with Sigismund of Luxemburg (1368–1437), who deposited the Imperial regalia in Nuremberg in 1424. The sketch is just an early idea, as the final paintings show significant changes.

Heute vor 1.200 Jahren starb #Karl der #Große | #gnm #nuernberg #bildnis #duerer pic.twitter.com/bKpI1qOqLX

— GNM (@GNM_Nuernberg) January 28, 2014

The paintings were intended for the chamber where the regalia were kept the night before their annual ceremonial display to the people. Today they are in the German National Museum in Nuremberg.

5. He had important patronage from the Holy Roman Emperor

Dürer continued his association with the Holy Roman Empire – in 1512 the Emperor Maximilian became the artist's patron. This meant that Dürer produced work for Maximilian and, in return, the artist's prestige was raised to new heights (often Maximilian failed to actually pay Dürer!).

One of the projects he worked on was called the Triumphal Arch.

The Triumphal Arch of Maximilian I

1515–1517, woodcut by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

This was an enormous image printed on 36 large sheets of paper from 195 separate woodblocks. It is around 3 metres wide and 3.5 metres tall, making it one of the largest prints ever produced. It was intended to be pasted to walls in city halls or the palaces of princes, and hand coloured.

Here's a video showing how the British Museum conserved their impression of it in 2017.

6. He influenced how Europeans imagined rhinoceroses for centuries

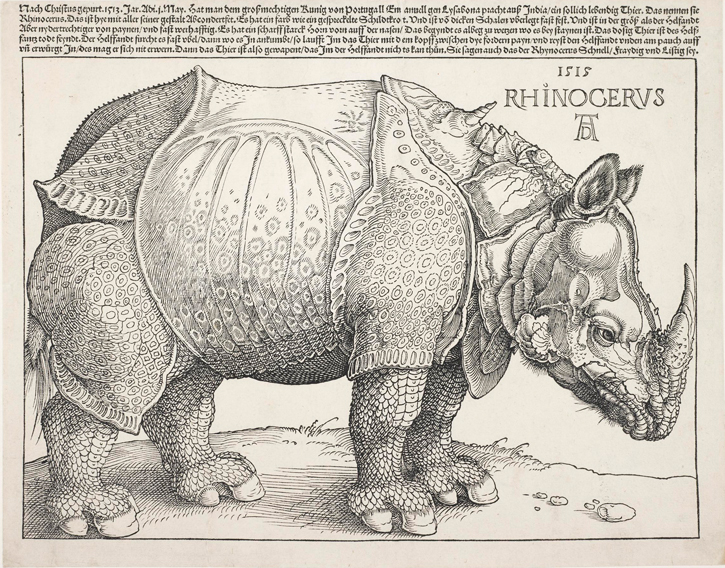

In 1515 the ruler of Gujarat, Sultan Muzafar II, presented a rhinoceros to the governor of Portuguese India, Alfonso d'Albuquerque. Alfonso duly sent it on to King Manuel I in Lisbon, where it arrived on 20th May. It was the first rhinoceros to reach Europe alive since the third century and therefore caused much excitement.

Dürer was asked to create a print of the animal, but he never saw it for himself. He almost certainly worked from a written description in a Portuguese newsletter that was sent to Nuremberg accompanied by some sort of sketch.

Rhinoceros

1515, woodcut by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

Not many Europeans had seen a rhinoceros either, so Dürer's version became the default that any European copied over the next few hundred years.

7. There's only one authenticated painting of his in a UK public collection

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it's in The National Gallery in London.

It's an early work, dating to 1496, and was probably made for private worship. It's a small double-sided painting with a few surprises.

Saint Jerome kneels in front of a crucifix wedged into the stump of a tree, in the wilderness where he lived for years. He beats his chest with a rock and his companion is a lion (one that looks distinctly not like a lion!). Much as with the rhino later in his career, possibly the young Dürer had never seen a real lion, so perhaps we should forgive him...

Dürer depicts the rest of the flora and fauna very precisely – even including two little goldfinches (traditionally a symbol of Christ's Passion).

The reverse of the painting depicts a dark sky and what might be planets, a comet or meteorite or an eclipse – quite unusual for the time.

8. He created a range of self portraits throughout his life

The silverpoint one made when he was 13 was mentioned above. But Dürer continued to create different versions of himself throughout his life. This one of him in a fur robe, painted in 1500, seems to be showing himself as a Christ-like figure.

Self Portrait in a Fur Robe

1500, oil on limewood by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

It also shows the influence of his thought around perspective and proportion.

9. He signed many of his works with a monogram

In many of his finished works, you will be able to find a monogram – a stylised A and D. This was his seal of approval, his calling card – in today's parlance, his brand.

You can even see it in this drawing, at the top right.

Few painters of the time signed their works so explicitly, so perhaps we should be grateful to Albrecht for such a distinctive (and cool) way to put a name on work.

It is perhaps also a sign of another aspect of Dürer's self image – he was an artist for the ages, rather than a humble craftsman.

10. He is extensively featured in a German episode of Monty Python

In 1971, the Monty Python team were invited to create a version of their Flying Circus show for German television. As it coincided with the 400th anniversary of Dürer's birth, they seemed to take inspiration from this.

Monty Python's Fliegender Zirkus includes a fake documentary (complete with animations of his prints) and a pretty odd song about the beloved artist...

Dürer remains one of the finest artists Europe has ever produced. His works are scattered across major museums, and the large house he bought in 1509 in Nuremberg is now a museum dedicated to him.

He excelled at various disciplines from painting to printmaking, and it was his adoption of the print that allowed his art to travel internationally during his own lifetime. His legacy has remained strong, and his works still have the power and immediacy they had when they were created five centuries ago.

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK