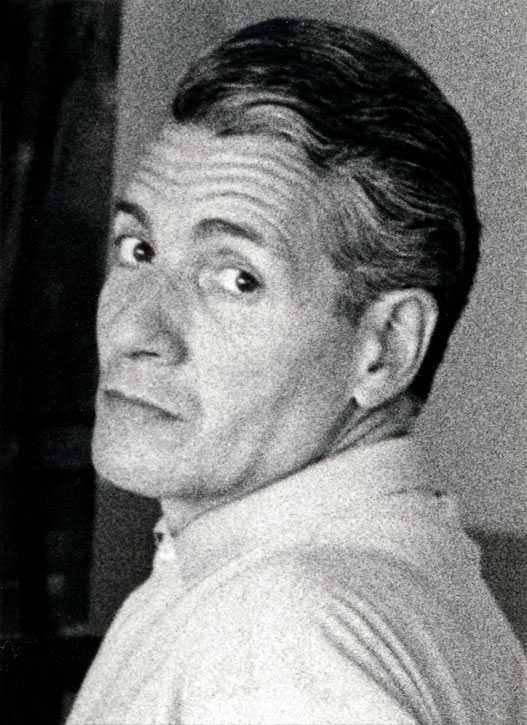

Looking at images from the 1960s of the chic, suave figure at the height of his success, rarely more poised than sat in a cherished Ferrari sports car, it is hard to imagine that before the second half of the decade, Luigi Pericle (whose full name was Pericle Luigi Giovannetti, 1916–2001) would turn his back on the art world.

Luigi Pericle

Yet that is the story of the Swiss-born painter who slipped into obscurity after he refused to exhibit any more after initial success across western Europe, though since the discovery of a stash of previously unseen works at his former home, Pericle's profile has been on the rise. Alongside other artists with metaphysical leanings, this painter's oeuvre is ripe for reassessment, a process that includes an exhibition at the Estorick Collection in London.

Raised in Switzerland with Italian and French ancestry, Pericle took up painting early on – he received his first commission aged 12 and enrolled in art school four years later. However, he soon left, disenchanted with its teaching methods. Instead, Pericle turned to illustration, starting out in 1942 with humorous graphics for a Swiss satirical magazine before moving to globally known American newspapers the Washington Post and Herald Tribune.

Luigi Pericle and his wife Orsolina

In 1947, he married Orsolina Klainguti, known as Nini, herself an amateur painter, and five years later achieved his greatest success in comic strips with the creation of cartoon character Max the Marmot. From its first appearance in the British magazine Punch, this impish mammal went on to gain popularity across Europe, the US and Japan. From 1954 to 2004, a book of comic strips, Max, was published in 25 editions. With proceeds from this bestseller, Pericle indulged his passion for sports cars, including the aforementioned Ferrari Spyder previously owned by film director Roberto Rossellini and his wife, Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman.

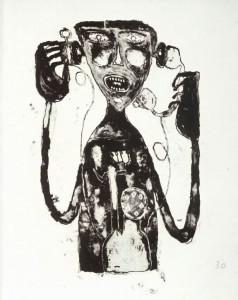

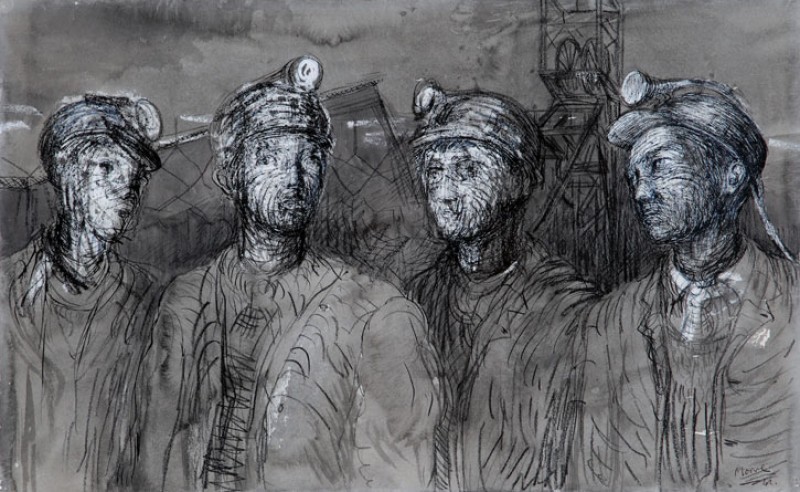

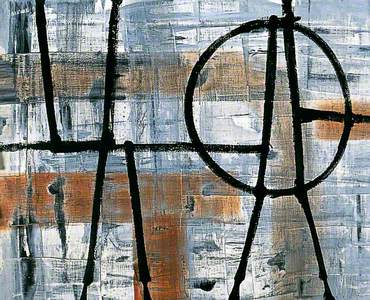

Untitled

1962, Indian ink on paper by Pericle Luigi Giovannetti (1916–2001)

Continuing to create art, Pericle kept the two strands of his output separate by signing graphic output with his surname, leaving the two forenames for paintings. Until 1958, the artist focused on figurative work, with that year seeing a dramatic turning point in his outlook that led him the next year to destroy all but one of his previous pieces. He moved instead towards abstraction, a style that would continue for the remainder of his short career and beyond.

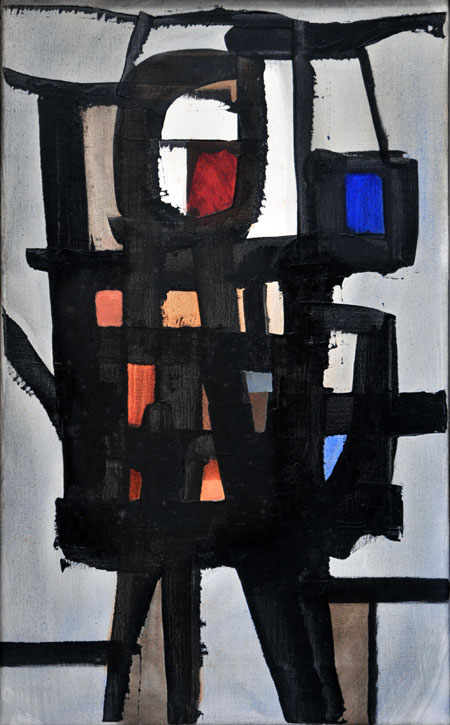

Installation view of 'Luigi Pericle: A Rediscovery'

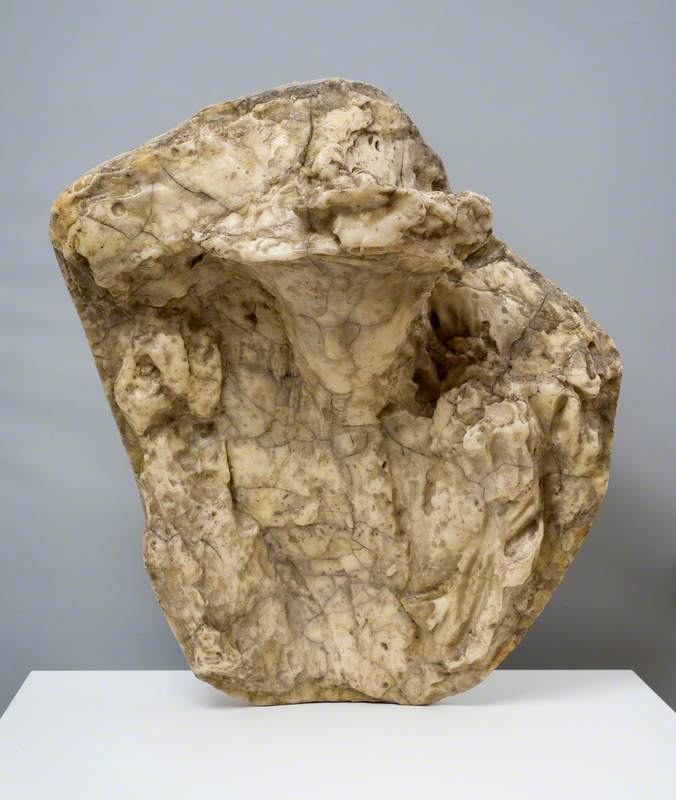

Pericle soon attracted interest for multilayered works of shapes that appeared partly symbolic and partly architectural, shimmering with metallic tones. While frustratingly enigmatic they exuded an intensity that reflected his metaphysical interests. From an early age, the artist had been fascinated by a range of beliefs, including Zen Buddhism, alongside ancient Greek philosophy and Egyptian religion. Above all, the artist had become attracted to the tenets of theosophy, a movement that from the nineteenth century had sought to introduce elements from eastern spiritualism, such as reincarnation, to the west.

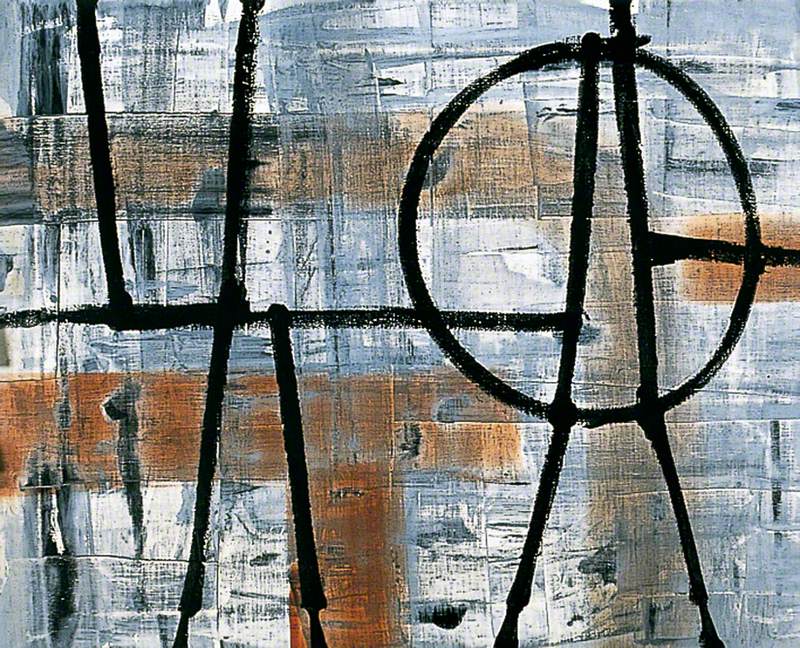

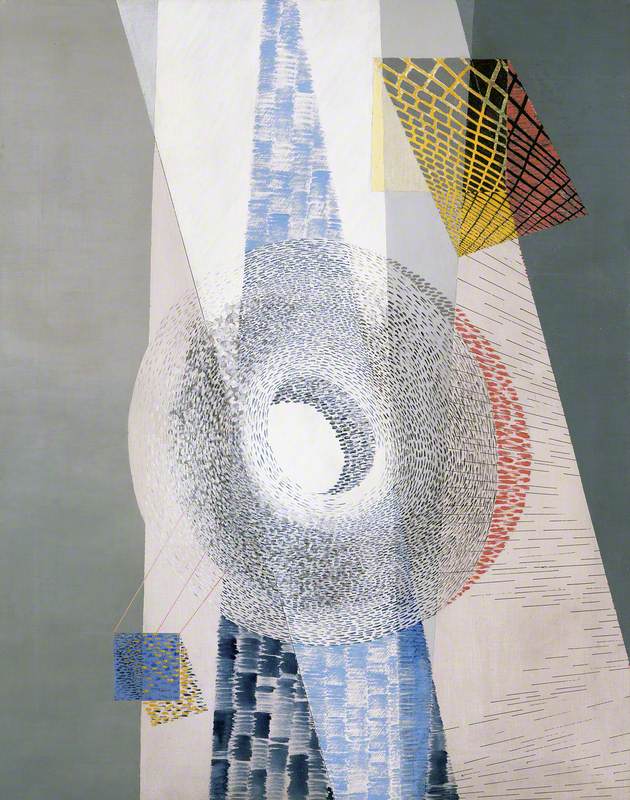

Calligraphic Rupture IV

1964, mixed media on canvas by Pericle Luigi Giovannetti (1916–2001)

In this respect, Pericle was following directly in the wake of pioneers such as Wassily Kandinsky, who long acknowledged a spiritual dimension to his work, while further back the likes of Hilma af Klint claimed to be channelling inspiration from higher powers. Indeed, a series of works by Pericle titled Calligraphic Rapture hint at that urge to delve beyond one's own intellect.

Pericle's rise in the European art world was swift: in 1959, he came to the attention of Basel-based collector Peter G. Staechelin, who acquired a 1930s villa for Pericle and Orsolina, previously home to artist and collector Nell Walden, wife of Herwarth Walden, editor of influential German arts magazine Der Sturm – to raise funds he sold drawings by Schiele and Klimt to the Leopold Museum, Vienna. Casa San Tomaso was in the former fishing village of Ascona on Lake Maggiore, where Pericle could surround himself with nature and tranquility.

Indeed, his new home was on the slopes of Monte Verità, famed since the end of the First World War as an artistic colony, reflected nowadays in the town's art museum that features work by the likes of Paul Klee, Marianne Werefkin and the German Dadaist Hans Richter. Even before then, the area had attracted a spiritual community that eventually founded a research centre, inviting such intellectual luminaries as Carl Jung to speak at conventions.

By the early sixties, though, the artist was enjoying interest beyond his homeland, showing at galleries in Italy and England, where he was represented by the well-connected Arthur Tooth and Sons in London. Displayed alongside expressionists such as Jean Dubuffet, Karel Appel and Jean-Paul Riopelle, he also enjoyed popular solo shows, possibly aided by having been outed in this milieu, to his chagrin, as Max's creator.

Still, this led to a 1965 tour of British museums organised by York Art Gallery curator Hans Hess and supported by the Arts Council that began at York, then went to Laing Gallery in Newcastle, Ferens Art Gallery in Hull, Bristol City Art Gallery, National Museum of Wales in Cardiff and Leicester Museum and Art Gallery. York still owns two of Pericle's works, including March of Time 1 (1962–1963), part of a series that feature circles floating in space that hint at portals to other places or dimensions.

While Pericle's work was well received, something about the experience caused the artist to withdraw from the art world to live privately in Ascona. In the Estorick exhibition catalogue, arts writer Thomas Marks points to Pericle's suspicion of the art market and also suggests he reacted to critics and viewers failing to respond to the metaphysical aspects of his work.

Instead, Pericle devoted himself to esoteric matters, immersing himself in a range of interests including parapsychology, astrology, UFOs and homeopathy. An urge to rid himself of material goods even led him to sell his beloved Ferrari (now itself a museum piece in France). In their essay for the catalogue to the Estorick show, the owners of Casa San Tomaso and custodians of the archive, Andrea and Greta Biasca-Caroni, explain this move by quoting from Pericle's own writings: 'All ambitions, pride and vanity must be forsaken... Love of applause, desire for glory, the reaction of ego must be abandoned.'

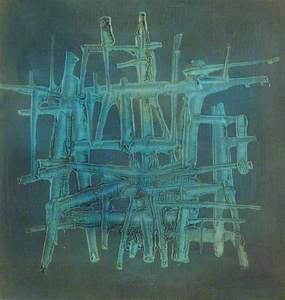

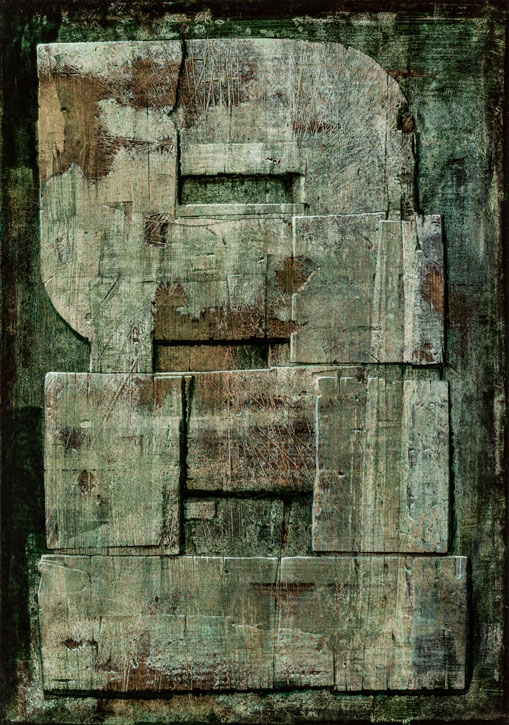

However, as the Biasca-Caronis discovered, Pericle continued to be visually creative, certainly until around 1980 when he dedicated himself to study and writing. This extensive series of paintings on the dense fibreboard branded Masonite, along with copious drawings, reflect his continued spiritual inspirations, though the denser textures tended to appear more organic. Academic and curator Martina Mazzotta in her contribution to the catalogue points to the regular appearance of 'gateways, thresholds, arches' among other shapes.

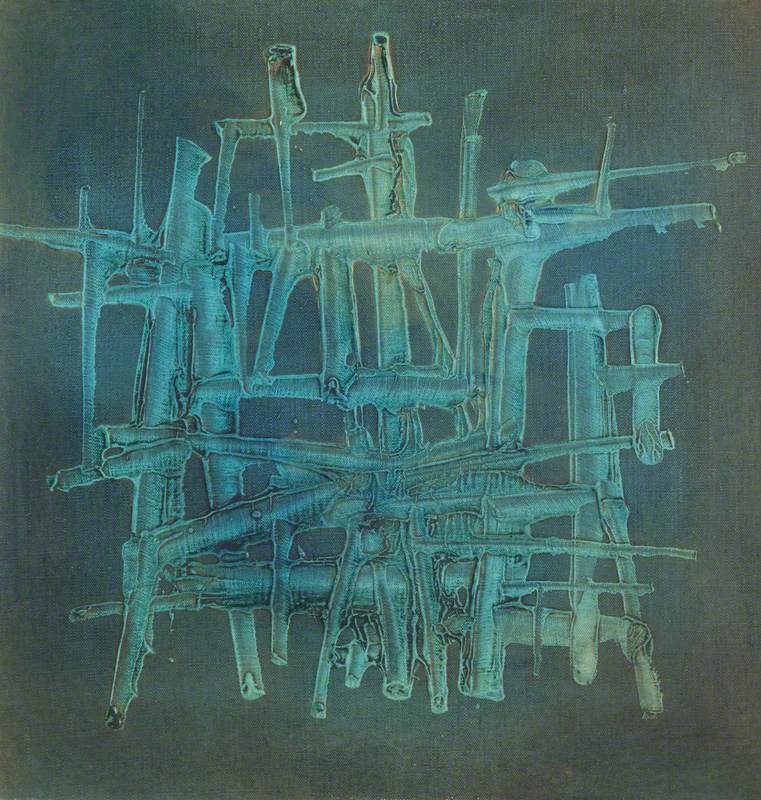

Untitled (Matri Dei d.d.d.)

1978, mixed media on masonite by Pericle Luigi Giovannetti (1916–2001)

Pericle corresponded with close confidants and his work continued to attract interest, although few guests were granted access and even some of those remained ignorant regarding his past. He met with near neighbour Ben Nicholson, who appreciated his work, and in 1970, the former Dadaist Richter, now better known as an art historian and curator, heard about this visionary hermit and in a letter to a gallery owner after paying him a visit reported, 'What I found was a very remarkable graphic and painting work, unlike anything I have seen before'.

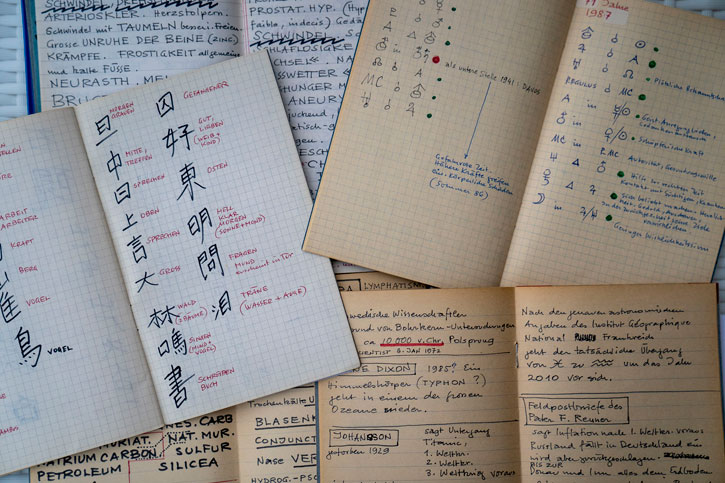

Handwritten study notebooks

Orsolina passed away in 1997, with Pericle following four years later, leaving no heirs. Their home lay abandoned until late 2016, when it was bought by the couple that owned a next-door hotel. Unaware of their neighbour's creativity, the Biasca-Caronis uncovered the artist's research archives and a trove of unseen work preserved in wooden crates. Belatedly realising its significance, they founded the non-profit organisation Archivio Luigi Pericle to restore, conserve and study this collection.

Since then, retrospectives of Pericle's work have been held in Italy: Venice in 2019 and two years later in Lugano. Earlier in 2022, the artist was represented in the group show 'Scribbling and Doodling: From Leonardo da Vinci to Cy Twombly' at Beaux-Arts de Paris and the French Academy, Rome. Studies are ongoing into his work that could lead to definitive connections between the artist's deep, eclectic research and his art, though these may only get us so far. As art historian and ICA co-founder Herbert Read wrote about Pericle, while is art is metaphysical, it 'remains faithful to the sensuous qualities of the material of the painter's craft... A long pursuit of an absolute beauty.'

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'Luigi Pericle: A Rediscovery' runs at Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art until 18th December 2022