What does it mean to learn national history from visual culture? I take up this question as a scholar of Mary Seacole, a figure who has steadily risen in fame and national significance in a post-1970s Britain keen on reforming its public image to include notable figures of colour.

Seacole was a Jamaican-Scottish nurse in the Victorian era who became a Crimean War hero, yet was overshadowed by Florence Nightingale's narrative. Seacole wrote her own memoir in 1857, but it's her visual legacy that I want to reflect on today, as it persists from her own era but especially after inclusion into the National Curriculum in modern times.

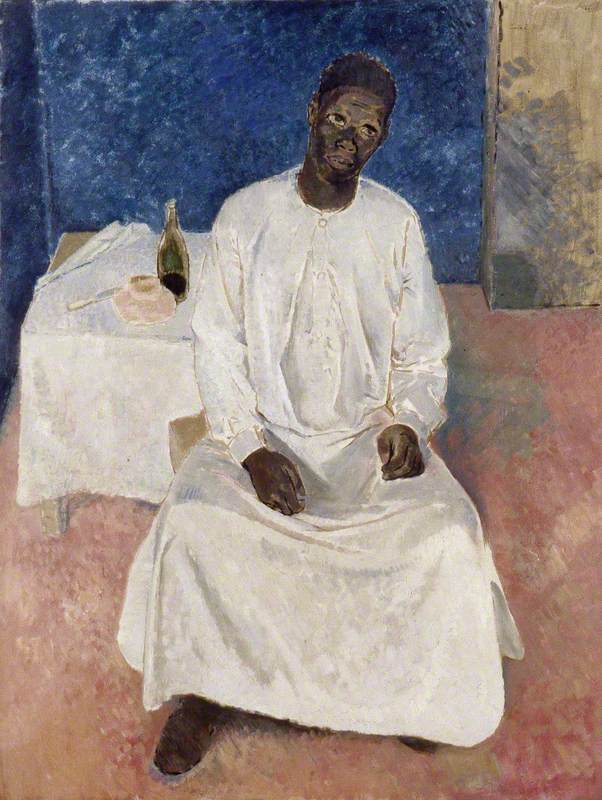

Mary Jane Seacole, née Grant

1869

Albert Charles Challen (1847–1881)

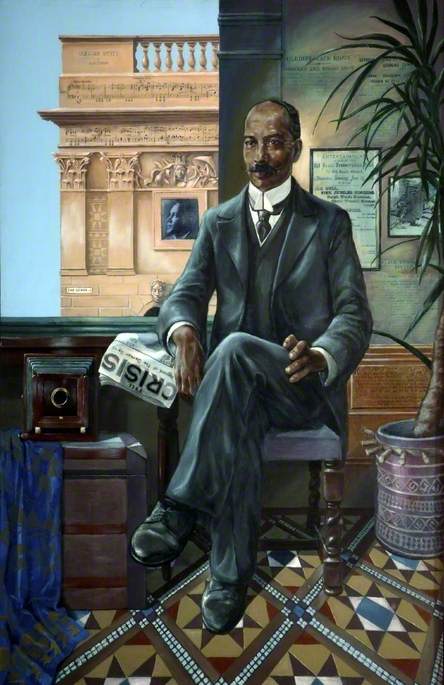

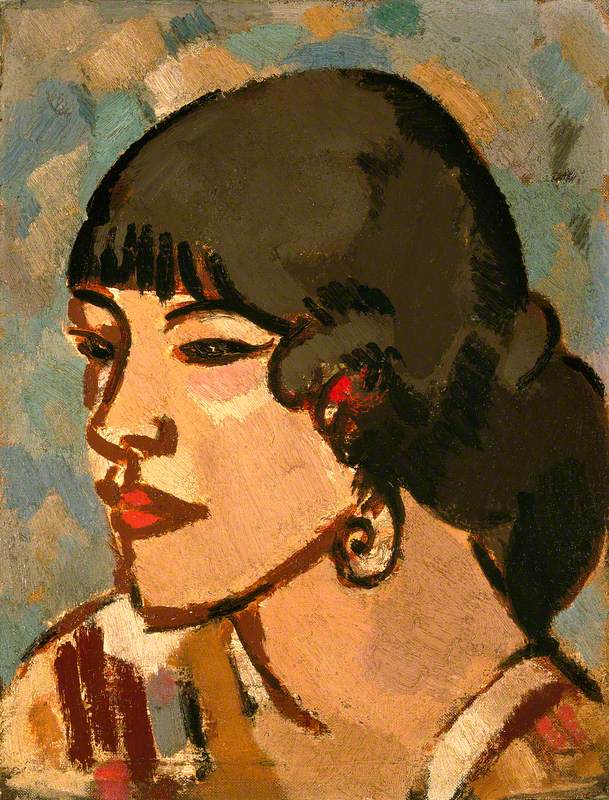

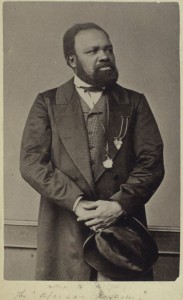

Seacole's visual representations in her own time included several illustrations in periodicals, particularly Punch magazine – showing her attending to patients or running her general store. Her 1869 portrait, now at the National Portrait Gallery, shows Seacole in profile, her 'war medals' on full display. A carte de visite from 1873 presents one of the few known photographs of Seacole, again with her war medals prominent, looking down as she performs mixing medicinal compounds.

An 1871 terracotta bust (yes, with her medals!) of Seacole sold for a tremendous amount this summer.

Just witnessed this terracotta cast by Von Gleichen (1871) of amazing Mary Seacole - Crimean nurse and inspirator - leave behind its £700 - £1,000 estimate to make £101,000 at Dominic Winter auctioneers. I hope she’s found a good home. We would have loved to have given her one. pic.twitter.com/1fFVVHSwxW

— Philip Mould (@philipmould) July 30, 2020

These Victorian-era representations of Seacole give us our portrait of stately 'Mother Seacole' at work, a war hero. They are in so many ways the ideal representations for the work of national inclusion that Seacole is meant to evoke – Seacole as national helpmeet, as a serious citizen of the British Empire.

Mary Seacole (1805–1881)

c.1873, photograph by Maull & Company, London

These images that focus on her work and her service are reproduced and re-rendered on the covers and websites of many educational materials – from BBC learning resources to children's books.

It’s wonderful when children read about Mary #Seacole #Education pic.twitter.com/A82vIuGSFa

— Mary Seacole Trust (@seacolestatue) December 13, 2018

As Seacole biographies pitched to children that have the weight of nearly exclusive representation of historic Black Britons – even as some fought and still fight the grounds for her inclusion – these materials bear more than the echo of the National Portrait Gallery piece's imprint. Seacole's image does the heavy work of standing in for nineteenth-century Black British history and identity.

In this way, the representations of Seacole based on her National Portrait Gallery portrait simultaneously manufacture a homogenous national history of raceless (read: white) citizenship and civic participation while they create a fiction of phenotypic difference. In other words, Seacole's image helps to shore up her British bona fides – service to the military, willing participant in the British empire's expansion and global projects – that don't rock the boat of existing white heroic figures, even as the Victorian renderings of Seacole morph to portray her with much darker skin, hair texture and styles associated with Black hair.

Naturalising racial difference ensures that Seacole can be dismissively referred to as 'the Black Florence Nightingale', seamlessly fitting into official histories as they stand while doing the work of making them seem inclusive and multicultural.

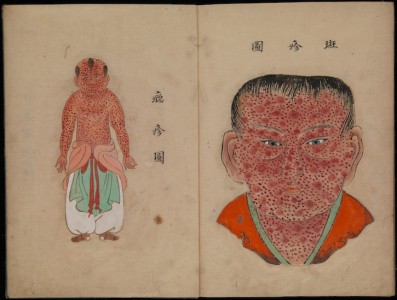

These racialised images of Seacole – adapted to her youth in children's book biographies, as well – tell several uncomfortable stories of British history in the Caribbean at once.

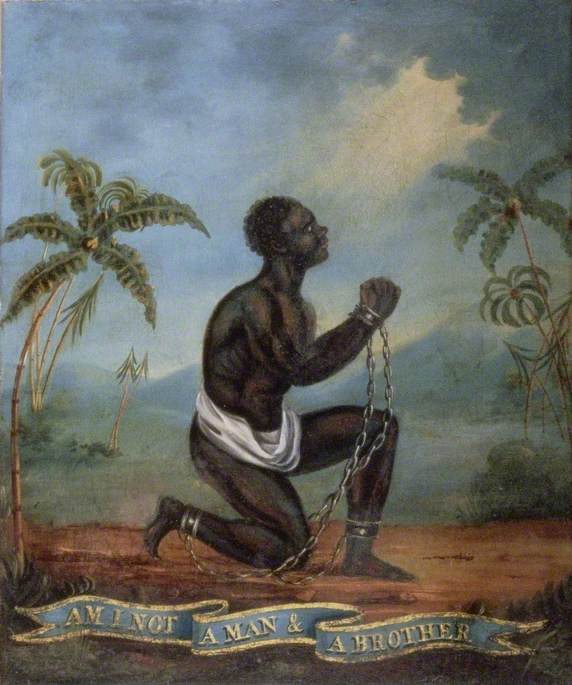

First, they erase Seacole's Creole identity, her proclaimed Scottish heritage, and the long-term history of intimacy between white British and 'Black' colonial subjects. Rendering Seacole in the ideal of Afro-Caribbean appearance papers over the well-known – if open secret – sexual and financial arrangements between British government officials and Jamaican women, as well as the complex history of the region's free Black and Creole populations in relationship to enslaved labourers, as well as to white colonial rule. It levels centuries of interconnectedness through the chattel slave trade with an image that imagines an unbroken line from the end of British enslavement, to Seacole, to the present day multicultural Britain (with maybe the Windrush in between).

Second, this hyper-racialisation of the image of Seacole elides white British histories of violent racism and 'colourism' that allowed Seacole to thrive where others could not. By reimagining her inclusion in British service as welcoming a dark-skinned Black woman, these inclusive histories rewrite some of the most virulent racism of the time and even now. Essentially, Seacole is recast in order to shine a less harsh light on British history – highlighting British 'tolerance' by representing Seacole as what is viewed as demonstratively Afro-Caribbean.

Mary Seacole, Paddington

Sustrans Portrait Bench

Third, and this is the tricky one: if Seacole stands in for Black and Caribbean history, if she is the singular hero of the story of these identities and regions in the Victorian era for British education, then showing her with natural hair, dark skin, and emphasising organic and local medical knowledge (as many of these texts and sites do) is a nod to the purported goals of multicultural education. In order to instil pride and allow a multi-racial group of students to imagine themselves as part of the national community, Seacole should look like those students.

Historically inaccurate and racially essentialist in some ways, yes – and doing PR work for the state, for sure – but representation also matters in education. These books and sites, drawing on and veering off from Seacole's National Portrait Gallery image, are part of the few historic stories of Blackness being told, or seen. Seacole's racialised transformation in accompanying illustrations and artwork pushes on her status as one of the only images of Blackness now popularly circulating from the period or in the British history learned in primary school.

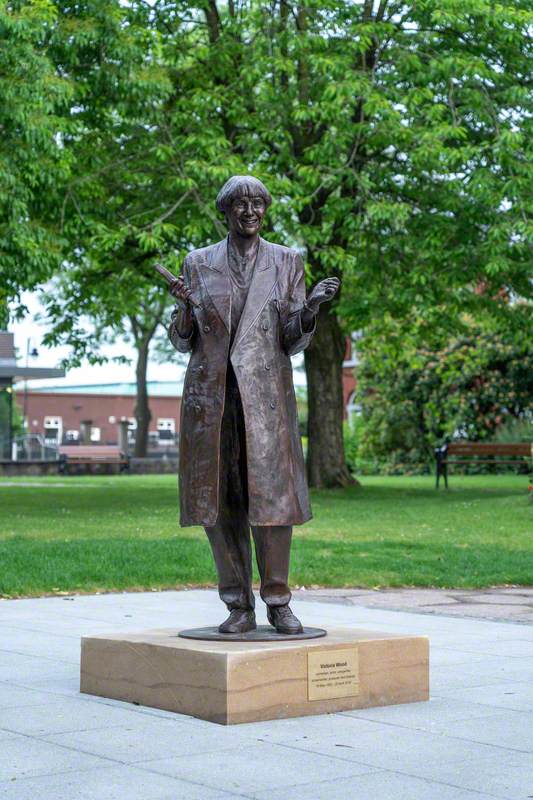

Knowing that the visual and the performative can stick and repeat in ways that, perhaps, stories can't (just think of the controversy over Seacole's statue – was it going to be too close to Florence Nightingale's? Was it going to be bigger?), where else might we 'look' for, and how else might we look at, Seacole, especially in the young student's classroom?

One place is Marcia Layne's gorgeous play for children, a play that stages interrelations – Seacole's early life in Jamaica, her first youthful visit to England, where she and a darker-skinned friend experience racism from white British citizens – that visualise the fullness of the Black and Caribbean experience.

Another might be the Horrible Histories videos dedicated to Seacole, ones that openly reflect on how history gets made or written (and one of which has an excellent dance sequence) so that students are taught not just about Seacole, but how to question the ways that figures come in and out of the historical light.

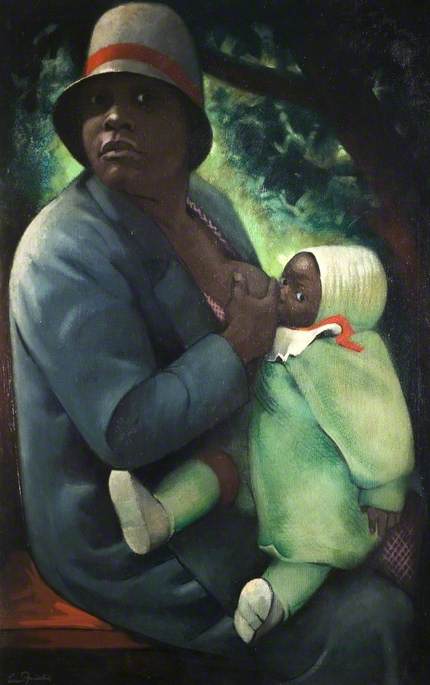

Another approach is to complicate how we look at Blackness – and who we look at – in this historical period. The exhibition 'Black Victorians' at Manchester Art Gallery that Caroline Bressey organised in 2005, and the wonderful catalogue of essays that came out of it, show some of the range – the possibilities – and limits of what the visual archive might offer when imagining Black British life in the period.

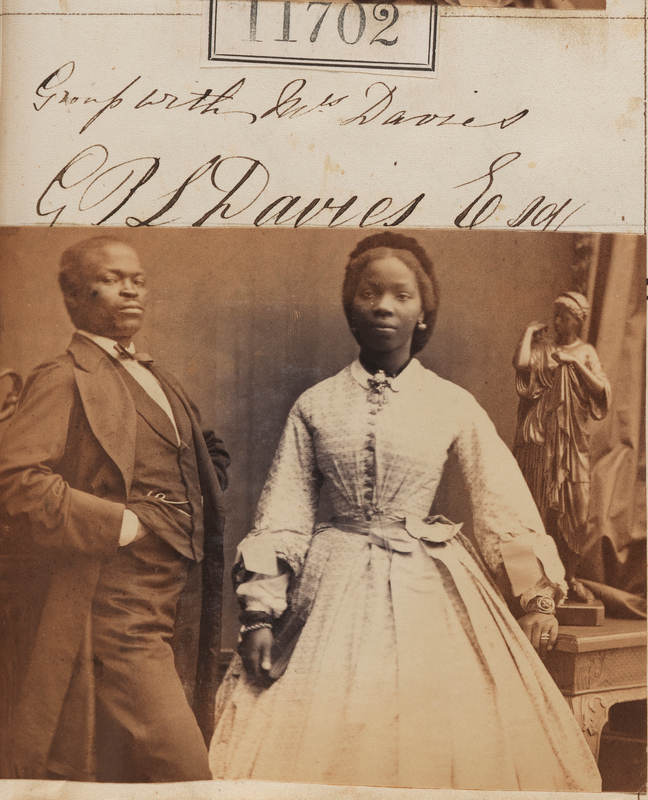

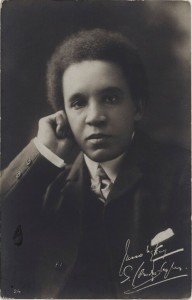

There are many more 'famous' Black Britons of the time to be recovered, for sure – for example, Ira Aldridge, Fanny Eaton or Sarah Forbes Bonetta. And there are also documents of black criminality in photography from prisons of the time.

As scholars like Gretchen Gerzina have argued, though, Black Britons were, by Victorian times, a relatively common sight in metropolitan cities like London. How might we envision communities and lives of ordinary Black Britons in the era, especially in ways that are dramatic enough for elementary education? How can these materials visualise Black British history beyond injury and inclusion, beyond the archest ways to 'see' race and racial identity, without eliding, of course, the racism that acutely and structurally mapped onto Black lives, then and now? Additionally, how can this be done without making those stories the only stories we can tell about the historical arc of Black lives, famous and unfamous, in the British historical record?

I wonder if some fine art and performance pieces might not alter the curricular vision of Seacole. Jackie Sibblies Drury's play Marys Seacole gives the audience both this historical aesthetic and connections to nursing and carework across periods and geographies, working with lighting and sets to dramatise the most intimate moments of emotional and medical care.

LDNWMN: Mary Seacole (1)

photograph by Heather Agyepong

Similarly, Heather Agyepong's new series on Seacole, the LDN WMN Project, decontextualises details of Seacole's life into visual form, envisioning Seacole's relationship to land and ecology and science through the lush (but decidedly not tropical or stereotypical) greens of introspective self-portraits-as-Seacole. In both Drury's and Agyepong's work on Seacole, 'care' isn't romanticised into service or heroism – it's shown as hard work, as knowledge, as difficult intimacies or, in Agyepong's series, the loneliness of being the only one in an historical narrative.

Both of these pieces push the line of what performer Dominique Moore in the Horrible Histories skits intimates: they allow Seacole to be complicated, ambitious for herself (not just for others), and even beautiful – beautifully lit, meticulously framed. There's nothing natural about the aesthetics of either of these final two pieces in the best way – they are staged, and they stage Seacole otherwise and alongside her aged portrait in the National Portrait Gallery, with its visible, golden-toned brushstrokes and emphasis on her service medals.

In the industry of visual representations of Seacole, they insist on pivoting the frame. Though markets in and for educational materials might not adopt these aesthetic strategies in full, they might embrace alternative aesthetics, and teach visual literacy as one way to decode Seacole's status in official British curricular history.

Samantha Pinto, author and Associate Professor of English at the University of Texas

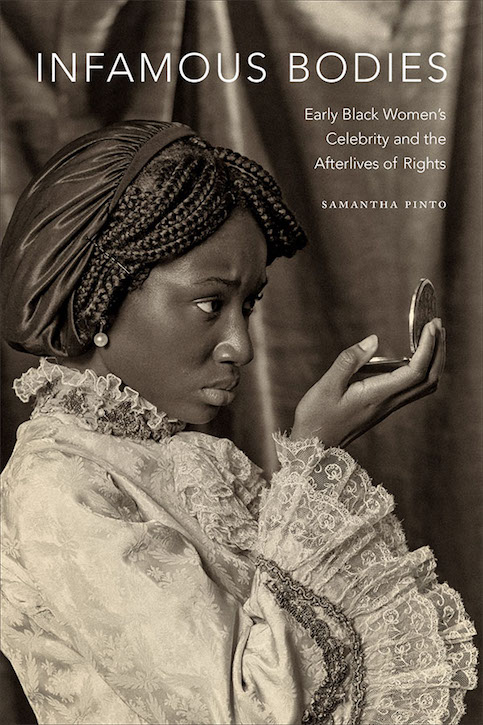

Samantha's book Infamous Bodies: Early Black Women's Celebrity and the Afterlives of Rights is available from Duke University Press